June 15–18, 2017

The air was hot and filled with din. Art Basel 2017 opened on Tuesday as a more laid-back affair than the previous two editions, but the overall mood was nonetheless upbeat. And how could it not be, given the breathtakingly vulgar fun-fair installation Now I Won (2017) by Swiss artist Claudia Comte, greeting and luring (and driving away) visitors entering the Messeplatz? Teutonic in execution and style, it offered various competitive games in which Comte’s artworks could be won while emitting a blaring mix of Schlager and hoedown techno. The proceeds from its two-franc ticket sales go to some eco non-profit, making the whole thing feel timely in its tribal tattooed populism-meets-greenwashing outlook, compared to resuscitations of 1990s virginal sharetopias like Rirkrit Tiravanija’s al fresco curry Do We Dream Under The Same Sky two summers ago, or like the kind of applied progressive “artistic research” embodied by Oscar Tuazon’s Zome Alloy architecture, underwritten by 2016 elites.

Inside, the demographic barometer had largely swung—or arguably remained—to a groomed, white Euro-set with noticeably Francophone accents to be heard nearly all around, perhaps due to some Emmanuel Macron high spiking French (or was it Belgian or in fact Swiss?) purchasing confidence and a restored appetite for the very best in reified jouissance. According to my own award criteria, best title of an artwork goes to Jutta Koether’s 2017 canvas Art Basel 17 Untitled / (Maximum Inspiration), shown at New York’s Bortolami. Rather than cynical, it is most of all transparent as artists young and old aim and are obliged to deliver for what remains the art world’s annual climax. Ballsiest—or most awkward—move goes to New York’s Petzel Gallery, where a sizeable Dana Schutz painting hangs as a centerpiece. On second thought, though, it isn’t inconceivable that potential and actual collectors of the work either are ignorant of or emboldened by the New York painter’s recent roasting following her contribution to this year’s Whitney Biennial, a canvas picturing the corpse of Emmett Till. Which brings us to:

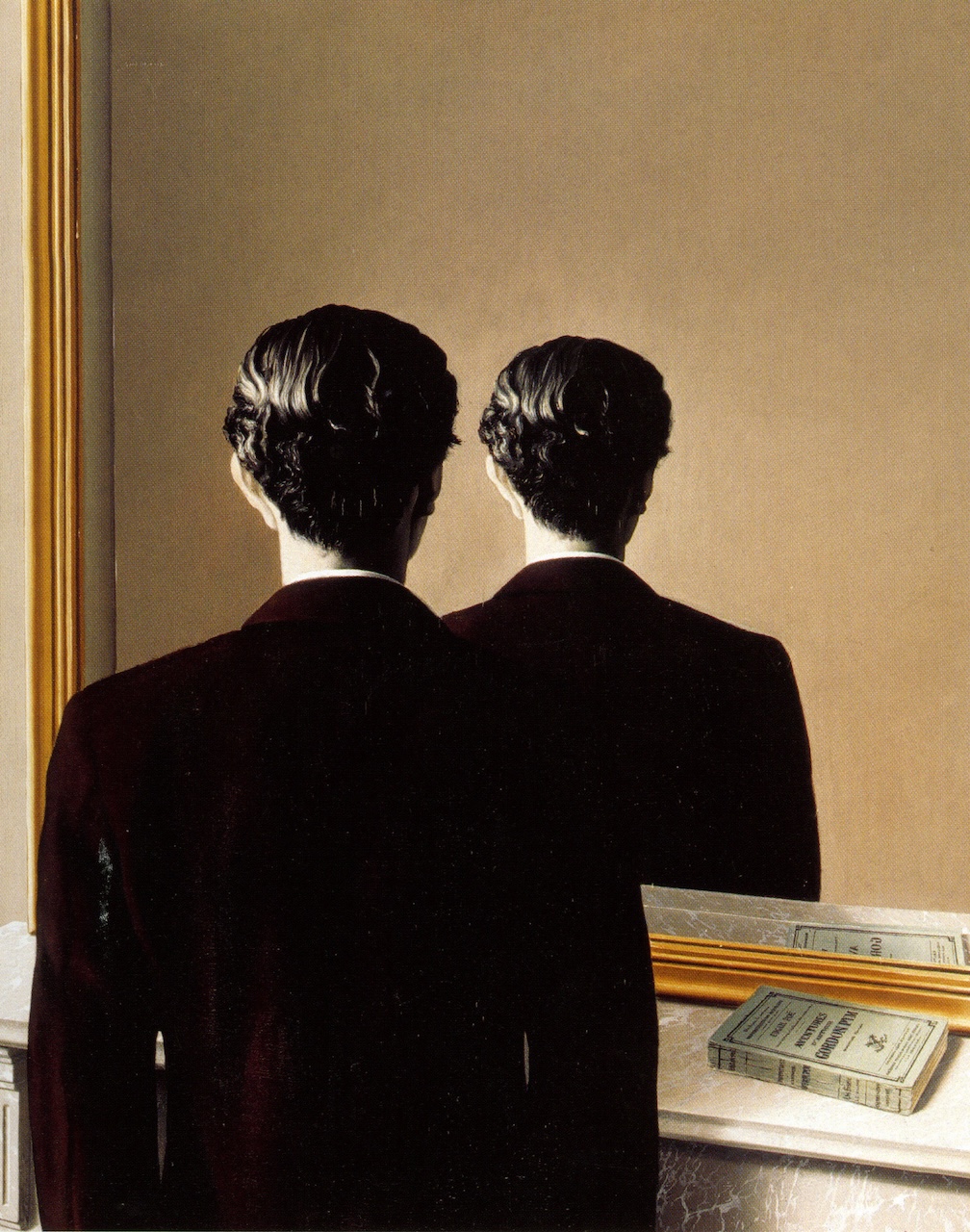

Hard numbers—specifically 600,000 USD for each of Alex Katz’s almost abutting paintings Bill 3 and Emma 3 (both 2017), which together adorn the front wall of New York’s Gavin Brown’s Enterprise. Only then and there did it occur to me that I couldn’t recall seeing an individual black subject, such as Bill 3, in any of Katz’s paintings before. (I’m far from being a Katz expert, but my Google search’s first hit produced, after some scrolling, a 1963 (!) work depicting a pensive male, entitled Kynaston, portraying the former MoMA curator Kynaston McShine, while the Bill in question is the dancer Bill T. Jones). Curious about the particular pairing, I was told by a gallery associate that the hanging was due to the two portraits sharing not only the same price tag but also the same dimensions—an uninspired and uninspiring answer but in hindsight maybe the most pro and drama-free reason to supply. Nevertheless, this identity-politics teaser that wasn’t took hostage of my viewing experience of the fair to come, continuing with a small, early self-portrait by LA-based filmmaker and artist Arthur Jafa at the same booth. Titled Monster (1988), it shows the artist in his late twenties in the final stretch of the Reagan era, depressing the button of his bulky studio camera as he exposes his not-yet-monetized image to a mirror and beyond.

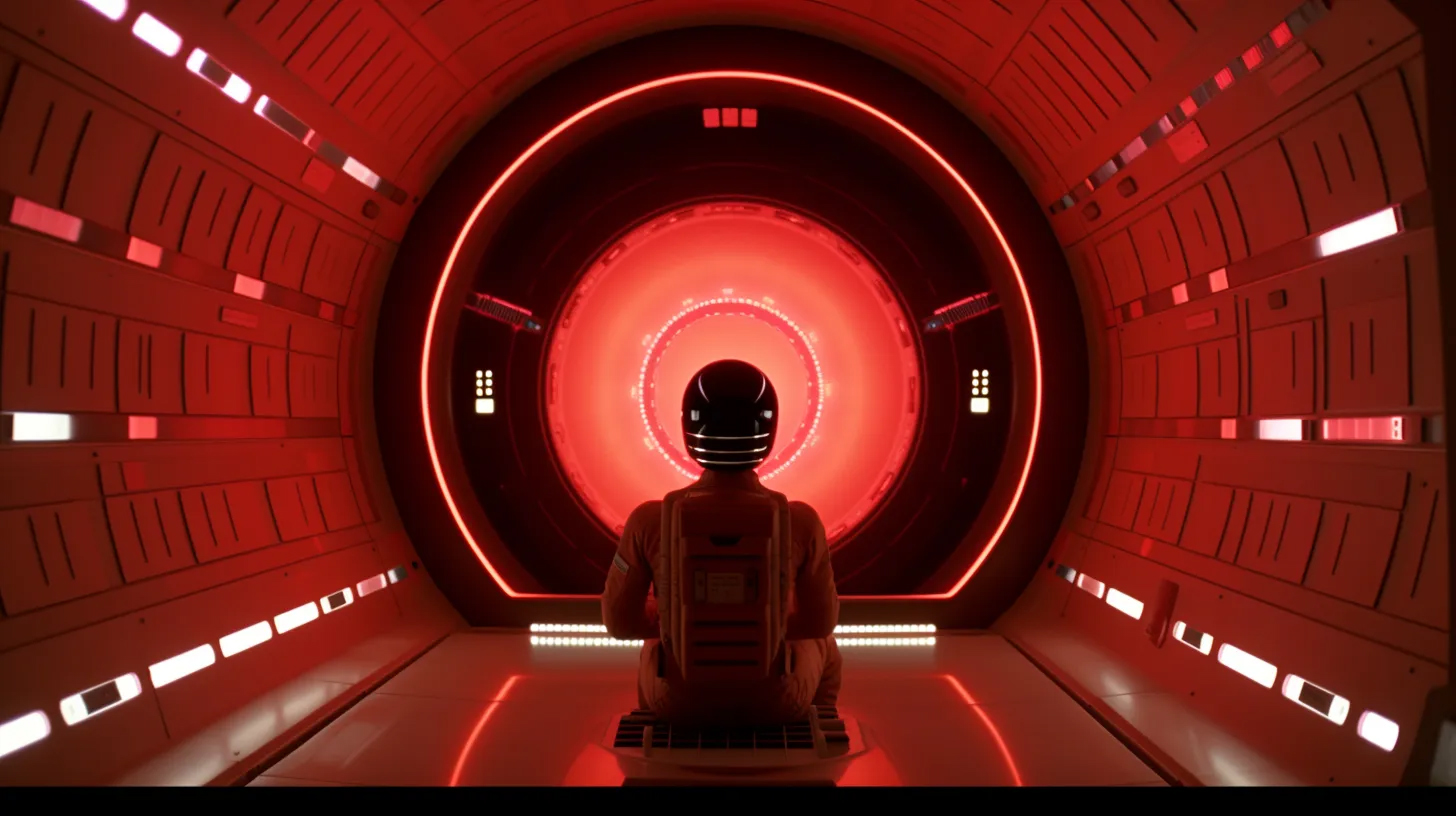

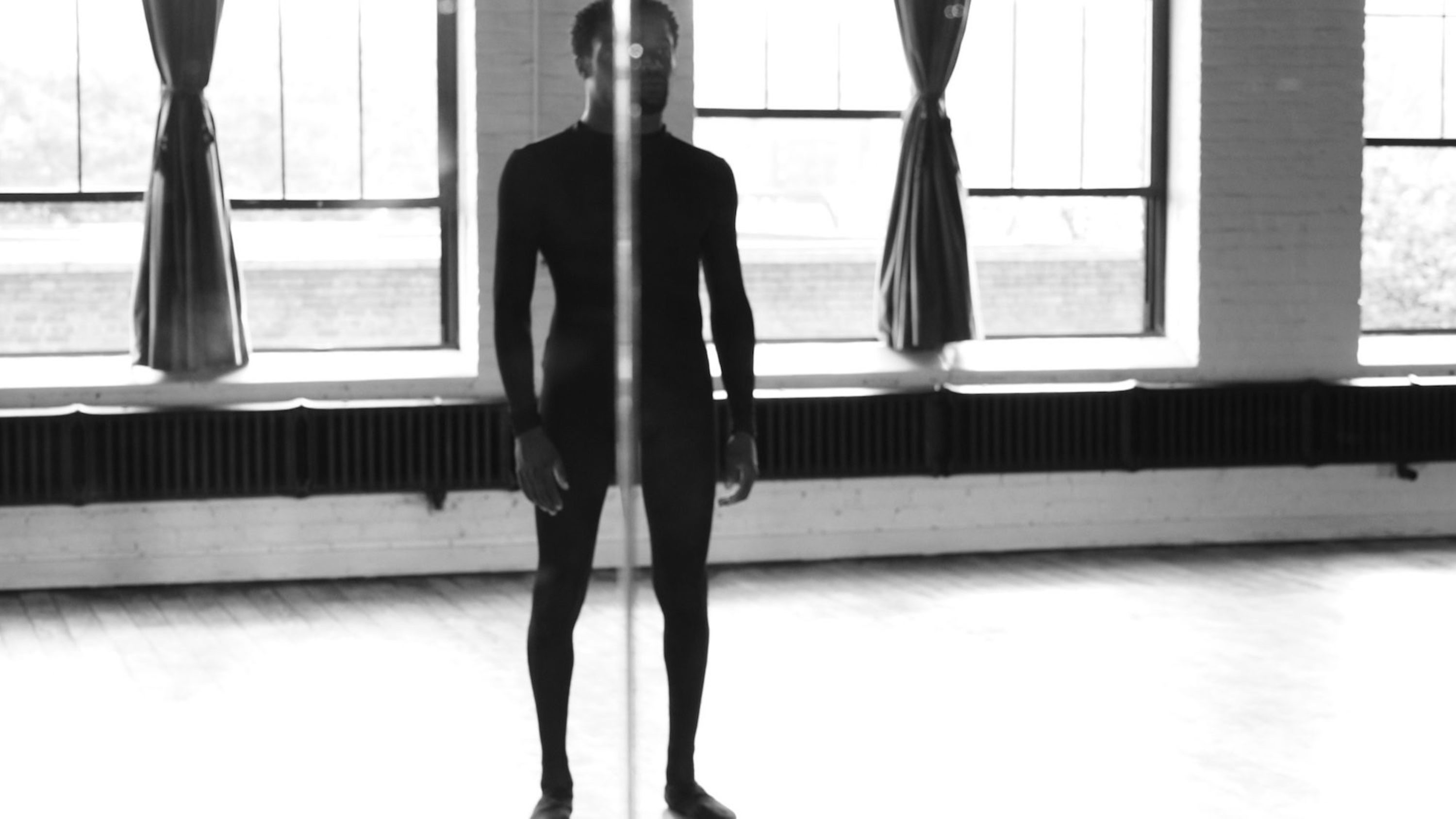

At Unlimited, GBE shows APEX, a 2013 video by Jafa, whose first exhibition with the gallery opened in 2016 at its new headquarters in Harlem to much acclaim. (All these strategic and territorial moves—the gallery now represents street photographer Danny Lyon, who is also shown at their booth, as well as Rob Pruitt’s hilarious installation Rob Pruitt’s Official Art World/Celebrity Look-Alikes [2016-7] at Unlimited, which celebrates the art world’s supersession of its alter ego, pop culture, which it’s wanted to conquer all along, pairing headshots of its various players with their mostly Hollywood lookalikes—suggest the gallery’s current position ahead of the pack). I saw the video here for the first time, watching it twice on consecutive days. Scored to a thumping Detroit-flavor techno track, the piece is as undoubtedly and viscerally engrossing as it is in fact simple in the way it employs montage as the time-tested tool of affective economy, and avant-garde cinema alike. (In other words, APEX could also “just” work as the very stylish creation of a V.J in a club, if that vocation still mattered.)

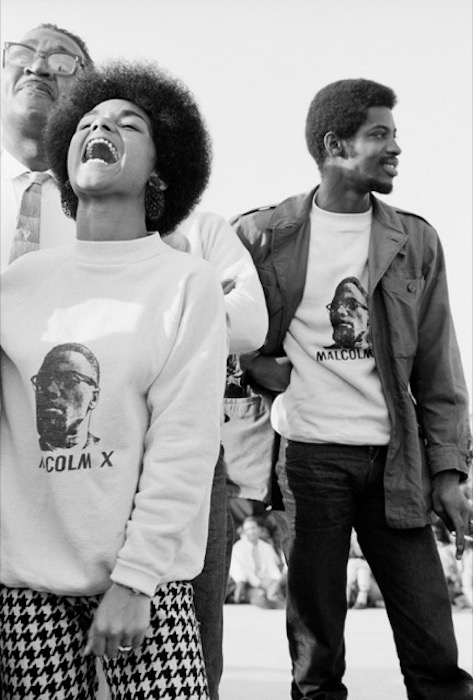

In rapid, transfixing succession, icons from Grace Jones to James Baldwin to Tupac light up the screen as do all kinds of marred and mangled black some-/nobodies, alien creatures, the aforementioned monster(s), and counter-cultural and mainstream stars such as Mick Jagger and Michael Jackson—the former famously co-opting black music culture and the latter famously struggling with just that background. What I took away from it was the however fraught return of the significance of authorship and the fast-proliferating awareness about it in contemporary art, for better or worse, within the polarized climate at large and the discourse about the representation of blackness and death in America specifically. What a few years back may have presented a “classic” issue of high versus low and the liquefaction of meaning and context through the digital has made the spectatorship of violated and commodified black bodies nearly inseparable from the daily headlines and tweets documenting concrete racial inequity and abuse, even in a place like Basel.

Just a few cinematic cubicles away, Mickalene Thomas also appropriates found footage, ranging from Whitney Houston concert recordings to comedian Wanda Sykes all the way back to Josephine Baker, in the mixed-media installation Do I Look Like a Lady? (Comedians and Singers) from 2016. This is however where the commonality ends. If Jafa’s resurrection of images linked to the black experience and its exploitation is one of exacting alienation highly attuned to capital’s pornographizing of everything—accelerated, in the work, to the point of delirium—Thomas draws instead on the heterogeneity of black femininity as an image pool tinged with nostalgia, tapped to congregate audiences old and new around it.

In the Features section, where each presentation is devoted to a single artist, Jenkins Johnson Gallery of San Francisco brought a plethora of striking images by LIFE photographer and blaxploitation auteur Gordon Parks, mainstream and commercial and endlessly ripped and certainly recycled over the years (including by the likes of Jafa and many before him). For all the risk of some kind of rehashing of Parisian 1920s fashionable “Black Deco” that essentially involved reinvigorating Western avant-gardism by lifting select tropes of otherness,(1) or plain and simple opportunism, this new sensibility in exhibiting, trading, selling, dealing blackness at the very least makes explicit this obviously rich social and formal art history in the making within the rarefied realms of Hall 1 and 2.

(1) See Rosalind Krauss, The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1985), 48 ff.