How the right foot of sixteenth-century Spanish conquistador Juan de Oñate came to be a part of the latest SITElines Biennial is a secret conspicuously guarded by the exhibition’s curators, but what is known about the appendage grants a revealing illustration of the thrilling noir that enfolds an object—or person, for that matter—when it enters the museum. The story begins 420 years ago on the Acoma Pueblo in what is today northern New Mexico. A dispute had erupted between the Acoma and members of the Spanish guard, leaving Oñate’s nephew dead. The colonial governor’s retribution was brutal: he ordered the mass enslavement of the Acoma and a foot cut off each man over the age of 25. Ironic, then, that a statue celebrating Oñate would be erected in 1993 at a visitor center dedicated to the area’s indigenous heritage. A local community claiming Spanish ancestry was responsible; four years later, a group calling itself the Friends of the Acoma cut off the statue’s right foot to protest the ongoing occupation of indigenous lands. Few have been permitted access to the original foot since.

Just like the statue’s initial provocation, the inclusion of Oñate’s foot at SITElines relies on symbolism, subterfuge, and sleight of hand. The curators appear to have opened the right backchannels, because a clay cast of the missing appendage greets visitors at the entrance, housed, like an archeological fragment, in a two-sided display case. The clever placement and design effectively suspends disbelief, with a nearby vitrine full of newspaper clippings and other information about the statue lending credence to the wonky facsimile. Whether the cast was fabricated or obtained, its presentation straddles institutional taboo, overstepping a curator’s responsibility to let the artists make the work. But the foot’s inclusion also raises questions about institutional transparency. The curators omit information on the statue’s immediate repair, and fail to address how the visitor center moved it to a more prominent position along the road. The point being that the foot underscores how any object, or artwork, holds the potential to be an instrument of power or protest. In any case, that this local conspiracy is entrusted to “Casa tomada” assumes a vote of good faith from the Friends of the Acoma.

Deception and storytelling are at the heart of this edition of SITElines, the third since the biennial changed its focus to the art of the Americas. Its title, “Casa tomada,” is taken from a 1946 short story by the late Argentinian writer Julio Cortázar. In electing not to translate it, the curators embark on the epic follies that have descended on Santa Fe, and put forward a salient pidgin that is irreducible to easy origins. The three curators—José Luis Blondet, Candice Hopkins, and Ruba Katrib, accompanied by Naomi Beckwith as curatorial advisor—organized a small biennial with a sole exhibition comprising 21 artists, and get away with their more daring gestures precisely on account of this intimacy and restraint.

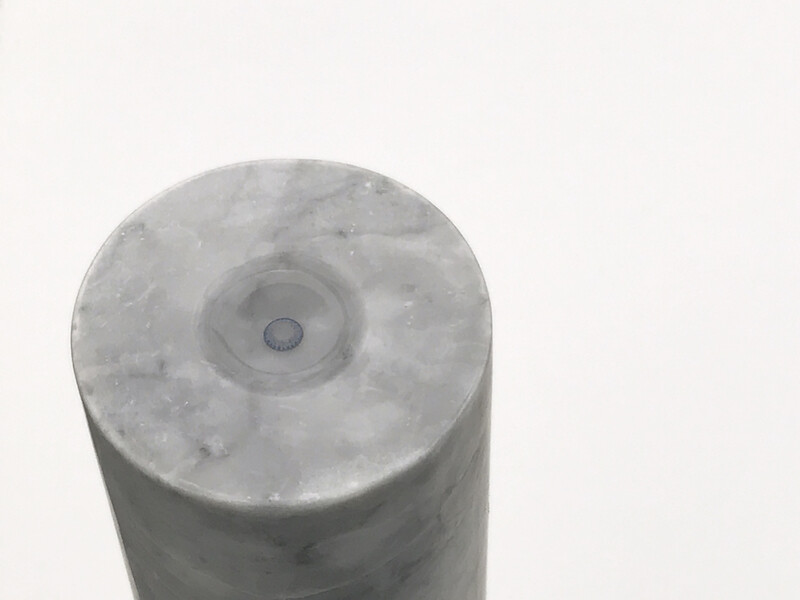

Hooked by the intrigue surrounding the foot, everything else comes to convey the uncanny feeling of a misplaced object. Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa’s precariously balanced mobiles “Revindication of Tangible Property” (2018) evoke rituals of trade and value. Cheap facsimiles of indigenous vases and French-inspired home decor dangle from beams that resemble the scales of justice. They are inspired by Mayan cosmology and also address Guatemala’s post-revolutionary zeal for foreign influence. Tania Pérez Córdova’s sculptures animate their materials using the language of absence. For Blink (2017), Córdova dug a small pool at the top of a marble column, filled it with saline, and preserved a blue contact lens there (the other lens, the materials list informs, is worn by someone, somewhere). There’s surprising congruity between Ramírez-Figueroa and Córdova’s fragmentary approach and Lutz Bacher’s billboard, Rocket (2016–18). Harkening to Los Alamos, the home of the A-Bomb, which is but a 40-minute drive away, it is a found photo advertising an enormous spaceship that has been quartered to reveal its working parts.

Narrative continuity is no guarantee of political compatibility but it grants the curators the ability to draw connections where trenchant structural boundaries had previously prevented them from doing so. The approach takes shape with prints and tapestries by Canadian Inuit Victoria Mamnguqsualuk, spotlighting their joyful eclecticism. The print Catching the Fish Mother (1979) exemplifies Mamnguqsualuk’s comic parables about humanity’s place in the animal kingdom: two people gently cast their bait, unwittingly fishing for two eager fish in their human likeness. According to Hopkins’s catalog essay, the crisis in the fur trade during the 1940s and ’50s represents an important turning point in how and why much native art was produced. Many native communities turned to the art market, and though necessity clearly granted someone like Mamnguqsualuk a prolific output, and commercial tastes were clearly not incompatible with the humor of her native iconography, the generations that followed have had to contend more directly with the reductivist ways indigenous art has been institutionalized in the mainstream.

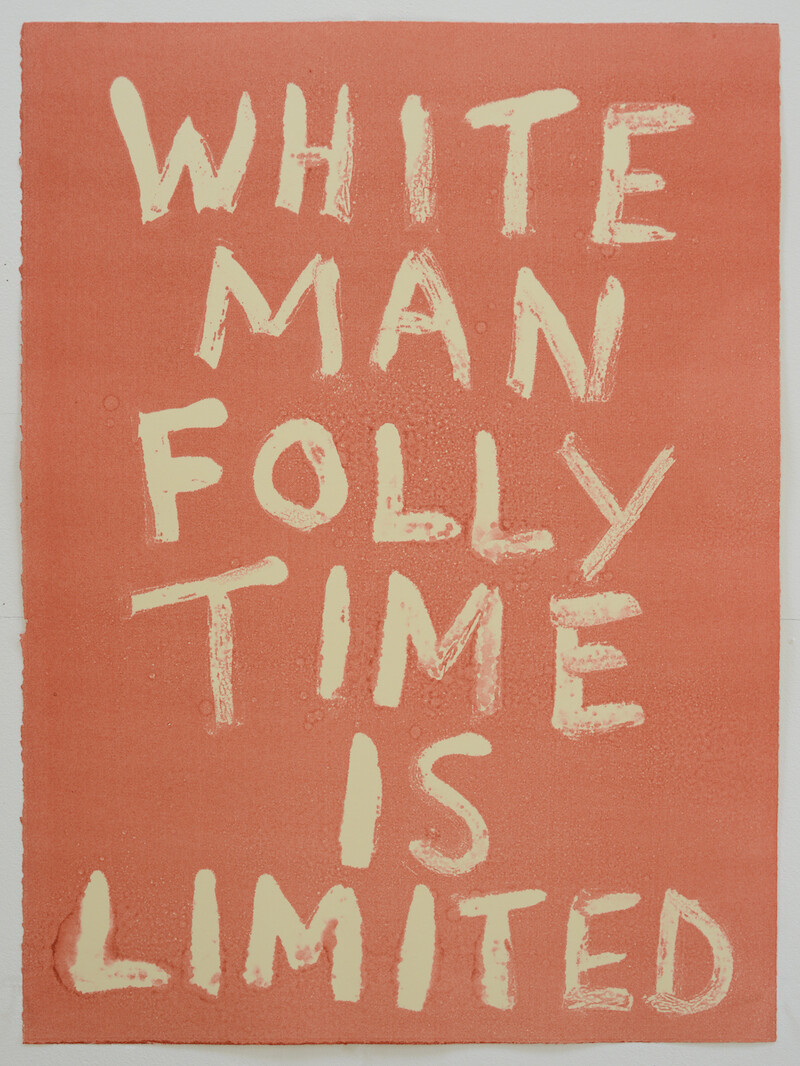

Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds’ Surviving Active Shooter Custer (2018), an enormous grid of monoprints of hand-written texts, combs many unlikely sources for language (song lyrics by The Police, to name one particularly funny example). This artist is enrolled in the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, and his wit and democratic sensibility pervades the various phrases. But when they read “Do Not Dance for Pay,” “White Man Follie Time is Over,” or “Stop Active Shooter Cadet Autie Custer,” there’s no mistaking his indictment of ideologically motivated euphemism. Elsewhere, another Canadian Inuit artist, Jamasee Pitseolak’s hand-carved stone tchotchkes speak to the labor and alienation that define indigenous handicraft: Domestic Sewing Machine (2006) depicts a fully functional miniature version of its namesake. What bitter irony that he dedicates all that skill and attention to represent domestic ingenuity, when it resembles thousands of mementos at Santa Fe gift shops. Laden Sole (2004) is more direct. It captures every detail of a boot, and the ball and chain attached to it. Heart-rending, how it could fit in the palm of a hand.

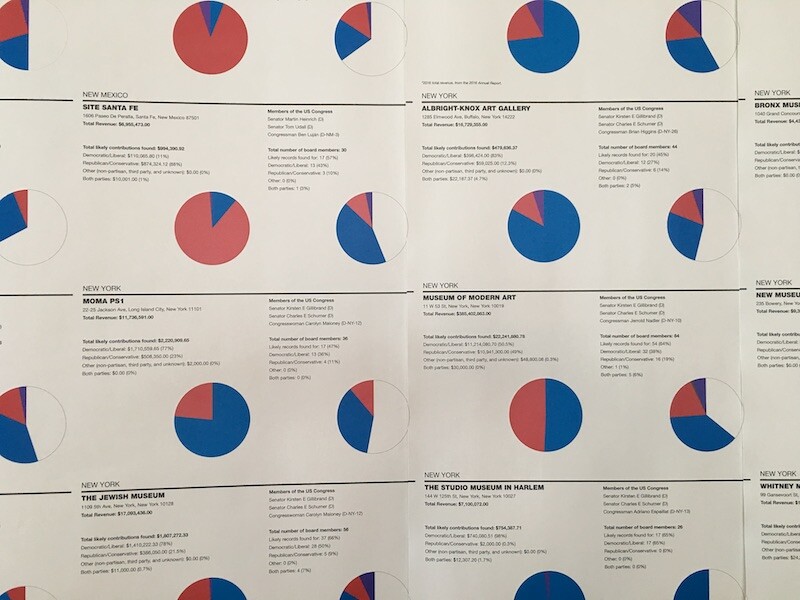

Puns and wordplay put forth potent critiques of institutional transparency, similar to what the curators have done with the foot. Giving artists the keys lends these tactics extra tooth. Stephanie Taylor re-interpreted the artist list as a disjointed heralding song with Press Release #2 (2017–18), which subbed in for the show’s official PR. “Lutz Stacker—Oh no that’s wrong. It’s Lutz Bacher,” a singer corrects himself. (Not only has the audio been sent out to press and listed on the website but Taylor’s comic tribute is piped into the bathroom, too.) Any museum prominently displays their donor list, but, plastered on SITE’s lobby wall, Andrea Fraser’s research project 2016 in Museums, Money, and Politics (2018) charts SITE and other museums’ board members’ campaign donations to the 2016 US presidential election. Gestures like these make the show appear a little self-involved and self-congratulatory, but Fraser’s institutional critique almost turns quaint when introduced by Taylor’s endless puns, and vice versa.

What remains captivating throughout “Casa Tomada” is what makes the foot such an inscrutable symbol: the search for truth. This is visible in works such as Jumana Manna’s documentary film Wild Relatives (2018), which follows the effort of the Global Seed Vault and Lebanese authorities to replenish a Syrian seed bank that was destroyed in the civil war. Momentous for being the first time seeds were retrieved from the Norwegian doomsday cellar, the film mostly addresses the Lebanese farmers, women who gossip, dance, and work in the fields. Elsewhere, Paz Errázuriz’s series of photographs, “Niñas (Girls)” (2018), expresses a supple take on the anthropological sciences. Taken during the 1960s and ’70s, the images offer a complicated, intimate, and sometimes even goofy look inside Chilean brothels. Errázuriz is aware that the camera complicates her role there. She also tracked down these women’s special sex worker cards, which were issued by the Pinochet regime. They accompany the photos, as if anyone needs to see some official ID.

While the truth behind the foot remains unverifiable—a potential double cross—it may also turn out to be the exception that proves the rule. The curators pull it off in plain sight, and their bold wager extends a crucial welcome to Sable Elyse Smith’s video Men Who Swallow Themselves in Mirrors (2017), which depicts Smith’s relationship to her incarcerated father while reflecting on, and questioning how, perceptions of black masculinity are generalized to represent a whole. A video message from Smith’s father forms the core of an inscrutable montage. Found footage of pointless gun violence, a spontaneous argument on the train, and other mundane scenes of public anger suggest that only from his jail cell can he recount with fondness the traumatic memory of when his daughter discovered his gun. Smith essays a rejoinder to her father’s missive, but it also conveys a larger story about personal consequence. With works such as these, the stakes of storytelling are made much clearer. “Casa tomada” reminds viewers that the politics behind the understanding of objects are just as tied up with the treatment of people.