“All great works of literature,” wrote Walter Benjamin, “found a genre or dissolve one.” This is no more true of a novel like Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (1913–27), about which the observation was made, than of works not typically recognized as literature. Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1922) and Philosophical Investigations (1953), for example, attempted and failed to dissolve the genre of writing known as philosophy, only to found a different one, whose audience is mostly to be found in the slice of the literary field adjacent to the art world. Although the series of numbered propositions in the Tractatus owe a great deal to the pseudo-geometrical proofs of seventeenth-century philosophers like Spinoza and Leibniz, and the numbered paragraphs of the Investigations were modeled after an aphoristic tradition that extends from Epictetus to Nietzsche, both books were recognized as significant literary departures from the stylistic norms of the academic paper, and have proven more influential among those working outside philosophy proper than within it.

Putting aside fictionalizations of Wittgenstein’s life such as Bruce Duffy’s The World as I Found It (1987) and Thomas Bernhard’s Correction (1975), this genre would include David Markson’s experimental novel Wittgenstein’s Mistress (1988), Guy Davenport’s short story “Au Tombeau de Charles Fourier” (1975), Rosmarie Waldrop’s collection of prose poetry The Reproduction of Profiles (1987), and more recently, Lars Iyer’s Wittgenstein Jr. (2014), Eugene Thacker’s Infinite Resignation (2018), and Maggie Nelson’s Bluets (2009) and The Argonauts (2015). Whether they adopt Wittgenstein’s numbering systems or not, these texts blend discursive and narrative modes, mix conceptual analysis with fiction or memoir, straddle the boundary between the prosaic and the poetic, eschew the continuous for the fragmentary, and are generally characterized by a melancholy tone that does not necessarily preclude moments of dark comedy. Hard to classify, Anglophone publishers have somewhat unsatisfactorily labelled the genre “hybrid writing.” Last year two further entries in the Wittgenstein-inspired mode were made available to English readers: Hermann Burger’s Tractatus Logico-Suicidalis (1988), translated from the German by Adrian Nathan West for Wakefield Press, and Róbert Gál’s Tractatus (2021), translated from the Slovak by David Short for Schism Press.

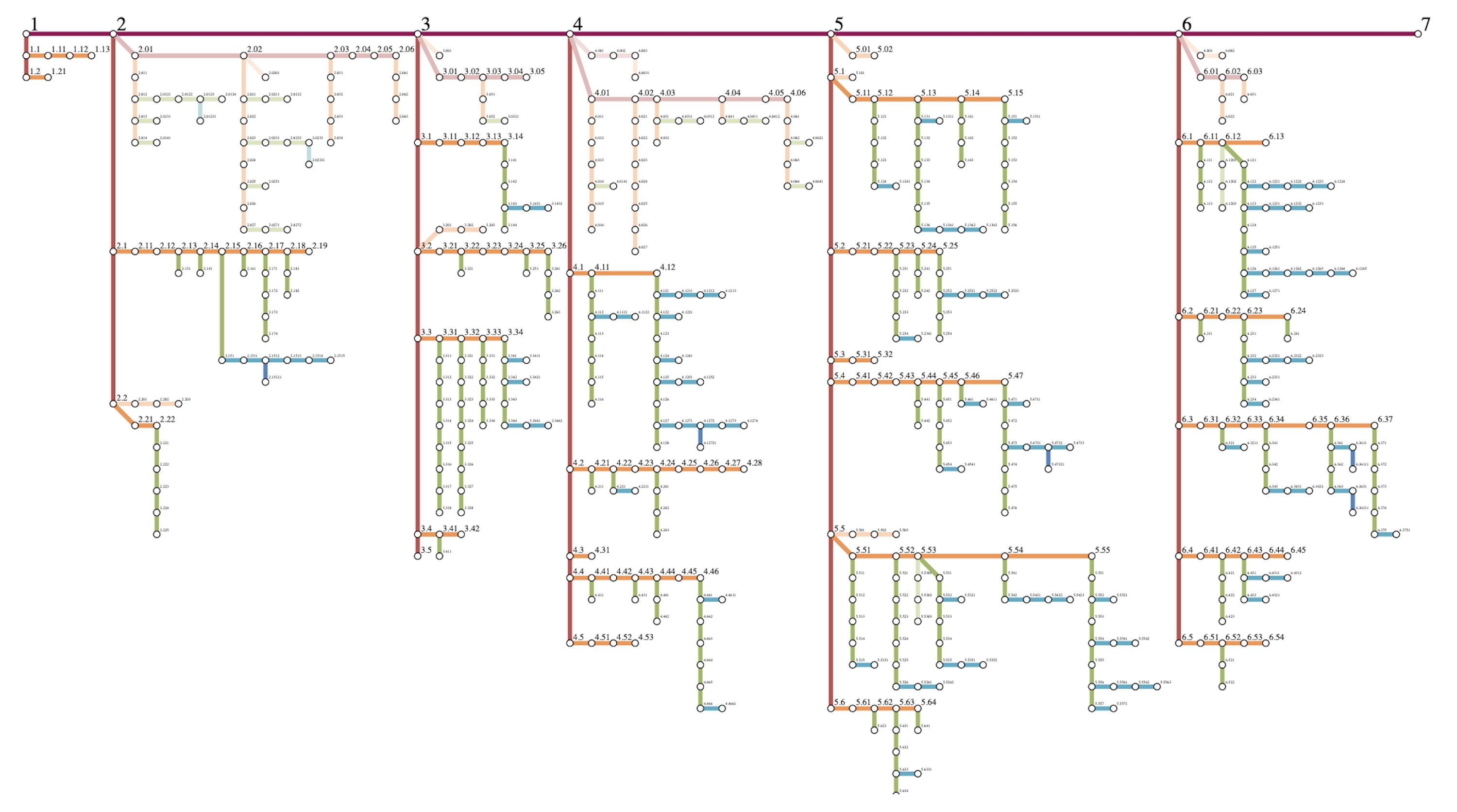

Like Wittgenstein, Hermann Burger was born to comfortable circumstances, in Switzerland, the next country over, during World War II. And like the Austrian philosopher, whose three elder brothers killed themselves and who often considered following suit, Burger’s preoccupation with depression and suicide are major themes of his fiction. Framed by a short story about the efforts of a small Swiss town to locate the missing body of one Hermann Burger, Tractatus Logico-Suicidalis presents itself as a found manuscript consisting of 1,046 aphorisms—or “mortologisms” to use the metafictional author’s preferred terminology—on the art and manner of ending one’s life. Part mock-treatise on “mortology,” the science of death, and part consideration of the history of “self-murder” in Western medicine, law, and aesthetics (Shakespeare, Kleist, Trakl, Kafka, Houdini, Camus, Plath, Améry, and of course Wittgenstein himself all make appearances in the text) the Tractatus is written with a pessimism that would have made Cioran clutch his pearls and a crankishness that would have made Bernhard blush. It derives much of its nauseating comic power from the spectacle of a rationality so obsessive that it passes into the territory of the deranged, where it trespasses the limits of good taste. When the text was first published, critics were quick to note the Bachmann Prize-winning writer’s gallows humor and grim irony; when, just over a year later, after a cycle of depression and mania, in which he wrote half of his four-volume magnum opus Brenner, Burger overdosed on barbiturates and alcohol, they were forced to concede that they may have been dealing with a suicide note.

More interesting than the absurd parsing (“To advance from suicidarian to suicidal is, in mortological terms, a promotion”), the self-negating logic (“There is no cure for death, but there is a cure for suicide: death”), or the deliberate provocations (“An ICU is the very definition of a peep show”), however, are the book’s reflections on art, creativity, and imagination. Burger seems to have intuited that the demand to erase the distinction between art and life put forward by the Dadaists of Zurich’s Cabaret Voltaire in 1916 and carried on to his own time by performance art pieces such as Chris Burden’s Shoot (1971) and Marina Abramović’s Rest Energy (1980) meant also considering death as a species of artistic practice. “In view of the nuclear and ecological disasters, the looming omnicide the world faces,” he writes, “the suicide’s solution is an artistic and revolutionary act.” Here the Tractatus takes on the quality of a manifesto and readers may come to see an underlying purpose of its intense focus on its morbid subject: a vindication of the creation of illusion over the acceptance of given reality. If “the creator refutes the theorem: de nihilo nihil” it is because she alone establishes the “dictatorship of imagination” over the real. Burger rails against therapy for sapping the creative impulse, but for him writing is not without its power to sublimate. He says: “No one need die after reading our Tractatus, because the tension of expectation vanishes into nothing—into mortology.” “Creation,” he concludes, “is the solution to the problem of death.”

“To give one’s death the contours of life” is also one of the stated ambitions of the Bratislava-born, Prague-based experimental writer Róbert Gál, whose previous collections of philosophical fragments include Naked Thoughts (2019) and Signs & Symptoms (2003). The twenty-seven sections of Gál’s Tractatus are at once more sanguine and abstract, more compact and broader in scope than Burger’s—and in all these respects it hews more closely to its namesake. Toggling between axiomatic assertion and rhetorical question, Gál ranges over topics such as the limits of language and the self, the nature of truth and knowledge, the metaphysics of time, and the valences of rationality and religious belief, but is no less concerned with the ethico-aesthetic question: how should a person be? Likewise rejecting the tidy division between life and art—here the art of thinking in written language—Gál argues that “what truth has in common with morality is not a matter of truth, but of morality.”

Having a concept of truth, in this sense, does not mean being able to accumulate empirical facts, as we often take it to mean, since facts, in and of themselves, stand outside of any relationship to how we live and die. Rather, “an assertion is true when its form becomes content.” In other words, a proposition becomes true not, as the Wittgenstein of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus would have it, when its structure mirrors that of the world, but when, as the Wittgenstein of the Philosophical Investigations would agree, its structure is assimilated to the lives of their users. If “life is too lively to be graspable” by propositions alone, Gál correctly states, that is because people are less knowers than they are seekers, finders, and players of games. People are beings who wait and remember, who experience pain and terror, who dream and imagine, which is, after all, a “manifestation of [their] freedom.”

Philosophy is also, in its origins, a way of breaking down the barrier between art and life. That is why conscious reflection on literary form and style, which academic philosophy ignores and which mainstream fiction takes for granted, are an essential feature of the “hybrid writing” genre to which Burger and Gál’s Tractatuses belong. It is precisely in their form that both earn the honorific in the quote from Wittgenstein Gál takes as his epigram: “philosophy ought to be written only as poetry.”