Andrea Bowers’s solo show at Jessica Silverman is marked by the artist’s signature combination of directness and nuance. Rooted in eco-feminist engagement and employing a wide range of media—neon signs, drawings on recycled materials, and video documentary—her deftly radical work calls attention to environmental degradation caused by patriarchal systems.

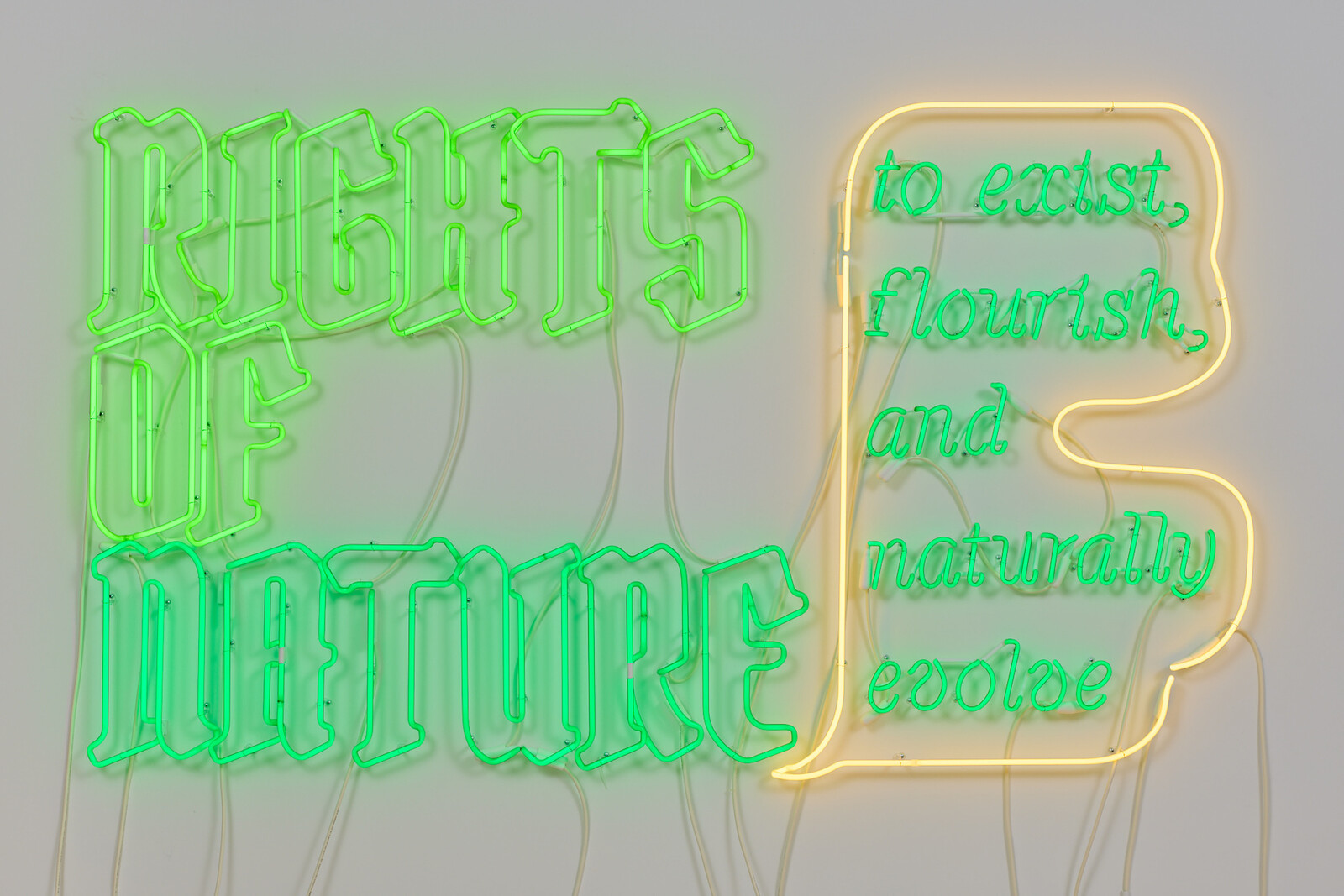

Bowers’s wall-mounted sculpture Rights of Nature I (2022) glows at passersby through the gallery’s street-level storefront window. Green neon tubing, styled in antique Gothic font, evokes legal documents while limning the piece’s title phrase. This in turn seems to emit a yellow speech bubble framing the words “to exist, flourish, and naturally evolve” in a contrasting font. This work builds on the use of neon by an earlier generation of artists—Deborah Kass and Bruce Nauman among them—as a communicative medium for political commentary, while continuing to play on and against its conventional employment in commercial signage. Though less dynamic than some of Bowers’s previous witty and sharply political slogans in flashing multicolor lights, it is among her most substantial: a heartfelt and lucid declaration that the Earth and other living creatures should be afforded the same rights, ethical treatments, and legal protections as humans.

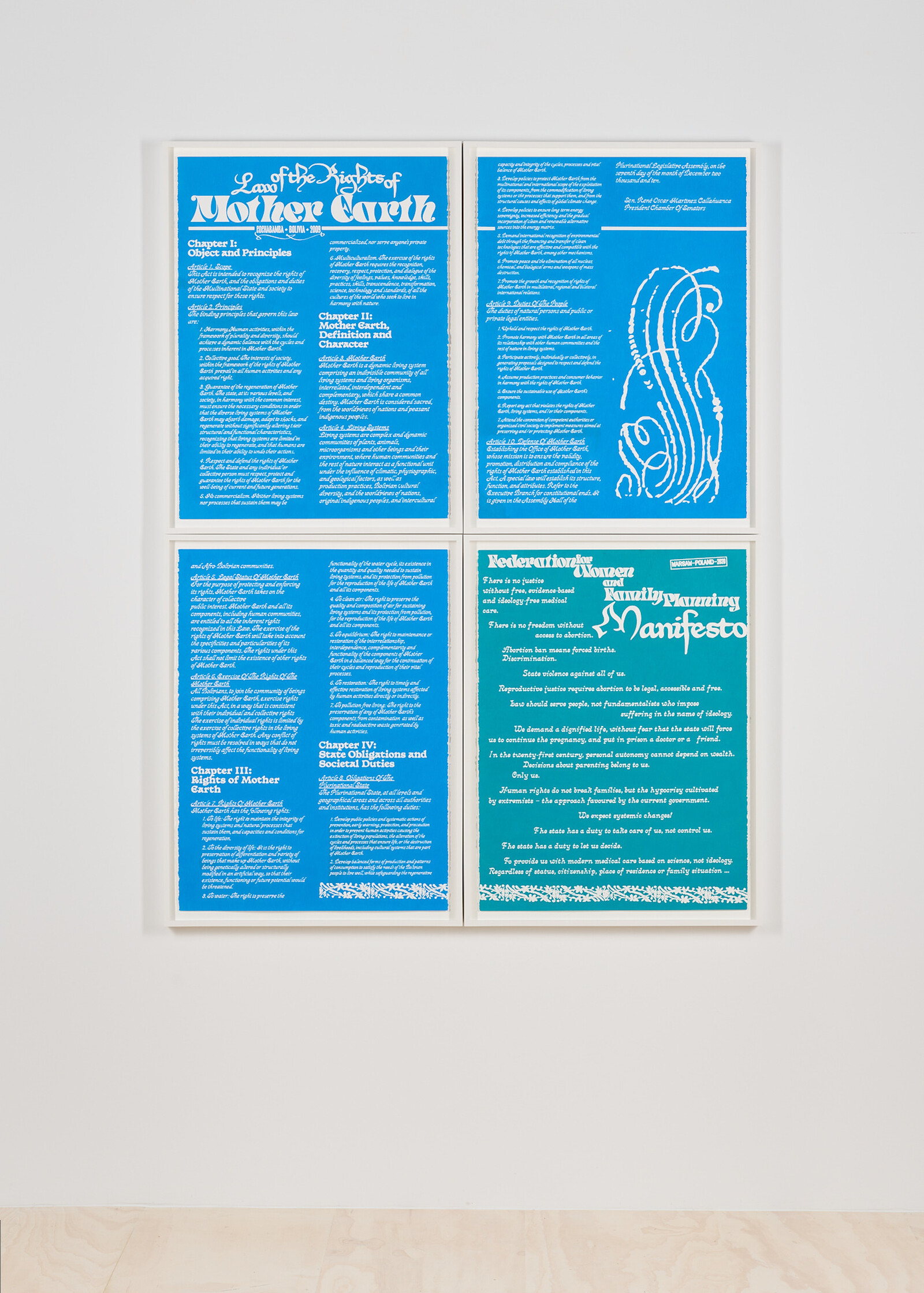

Within the gallery, a sister piece is mounted on the wall. Rights of Nature & Bodily Autonomy (Law of the Rights of Mother Earth, Bolivia, 2010; Federation for Women and Family Planning Manifesto, Warsaw, Poland, 2020) (2022) replicates declarations of fundamental social, political and environmental sovereignty in words and images with labor-intensive color fields and careful lettering drawn by hand in pencil on paper. Nearby, a second hanging neon piece embodies the message held forth by its title, Chandeliers of Interconnectiveness (Everything Is Part of Everything Else) (2022), inscribed in steel, shaped into forms of hanging branches with leaves highlighted in neon.

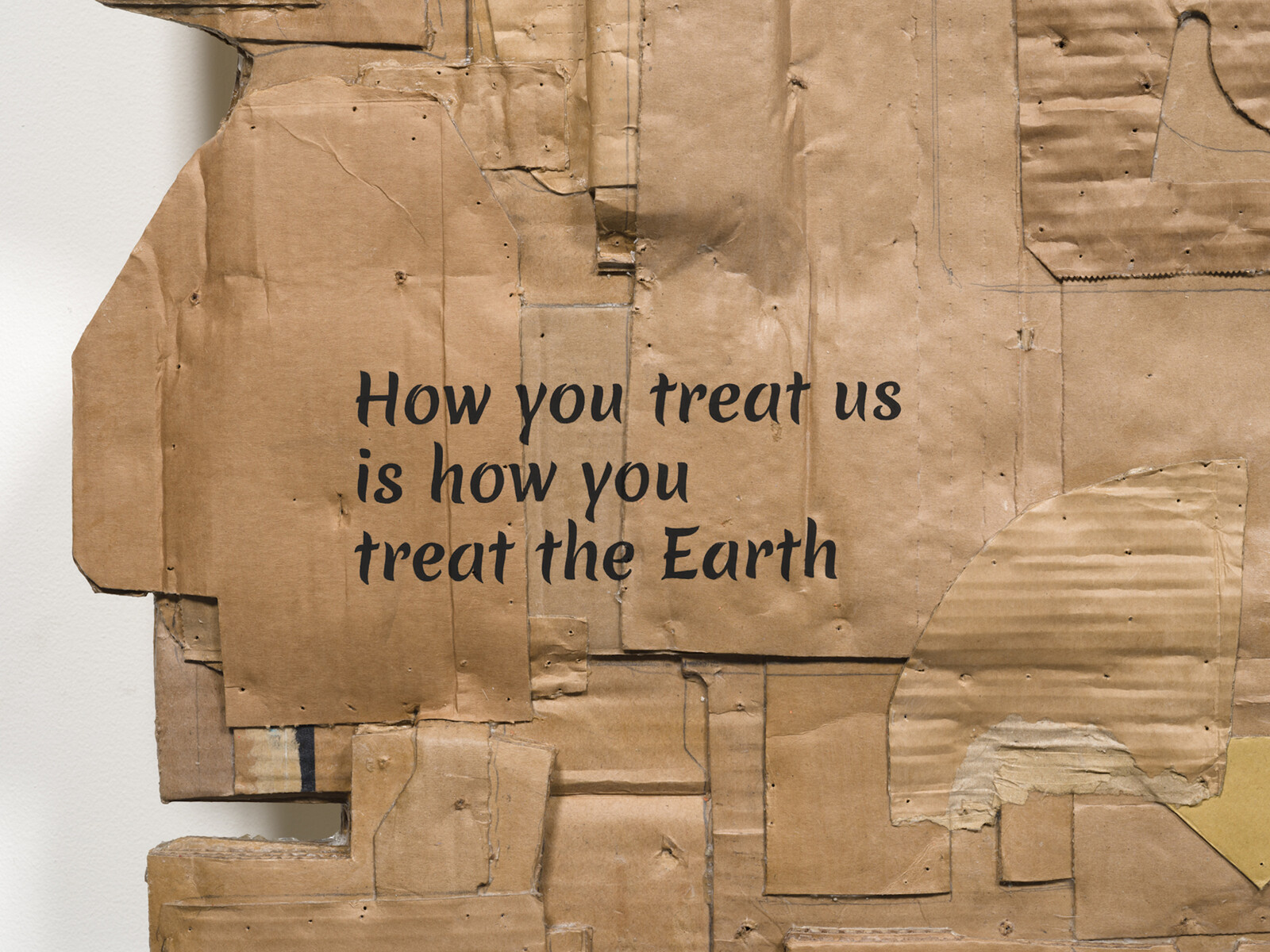

The life-and-death stakes of failing to recognize the “interconnectiveness” of living things, and their larger environmental surroundings, are displayed in three large-scale drawings on cardboard in Bowers’s “Eco Grief Extinction” series, vibrantly rendered in acrylic colors while combining sets of materials and re-appropriated imagery from the turn of the twentieth century. Bowers pairs haunting portraits of three bird species—the Molokai Creeper, the Bachman Warbler, and the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker—recently made extinct by human environmental impacts, each accompanied with re-creations of vintage illustrations or more contemporary female human forms, representing our survivor species’ parallel demonstrations of vitality, vulnerability, and mourning.

Cardboard, in these irregular, intensely pieced-together panels, becomes more than mere background for the figures. Instead, it’s insistent in its own textures and the committed weaving together of numerous fragments of repurposed paper products—recycling as manifesto against unquestioning modes of resource extraction, accumulation, and monumentality. Bowers’s use of cardboard as more than a material base points to her longstanding work around safeguarding old-growth trees, the living beings from which this manufactured packaging material derives.

Facing these representations of grief from across the room, Bowers’s 2022 video Landscapes We Call Home, Redwood Forest Defense, 2020 documents activism countering further loss of life. While avowedly less belligerent than groups such as Extinction Rebellion and Earth Liberation Front, members of the Redwood Forest Defense, shown embedded high in the canopy of redwood trees in Northern California, militantly oppose not only the clear-cutting lumber industry but prevailing extractivist ideologies that support such rapacious commercial methods. Projected larger-than-life, these activists put forward the emphatic yet nuanced analyses that can only be generated through experiences of life outside conventional society. The direct address to viewers by protesters who put their own bodies out there makes these revolutionaries—and revolution itself—seem not only reasonable but acutely necessary to protect individual trees while intervening in a deeply flawed social order generated by capitalism.

If monuments are meant as enduring reminders of past events and human figures, then Bowers’s material choices pose a series of anti-monumental challenges to who and what have historically been represented as cultural icons. Such investments are, of course, disturbingly and dangerously present, looming over our common future and affecting everything from individual psyches and social relationships to the reckless and permanent destruction of manifold living species. Bowers’s work calls on viewers not simply to get back to nature, but to pro-actively defend our interconnective world against human onslaught.