Curated by Houston-born curator Jennifer Teets, “Intimate confession is a project” looks at what her academic inspirations—Lauren Berlant, Ara Wilson, Kai Bosworth—have called “affective infrastructures.” Here, the phrase denotes a way of thinking through how infrastructures, designed to facilitate the movement of goods and people with maximum efficiency, can produce varied emotional affects.1 In a catalogue essay, Teets writes that this group exhibition is “informed” by Houston. Here, perhaps more than anywhere else in America, infrastructure is the city: the crumbling roads, the non-existent sidewalks, and the looming if stealthy presence of oil refinement and finance.

The show opens with model houses made from old Bible covers by Chiffon Thomas. Attached to the ceiling over the staircase to the exhibition floor, they hover like ghosts. Thomas was inspired by the neighborhoods of his Chicago childhood, but the shaky silhouettes of these model houses could be Houston’s Third Ward, or any poor community where a church promises a better life perspective than the current economy and policy.

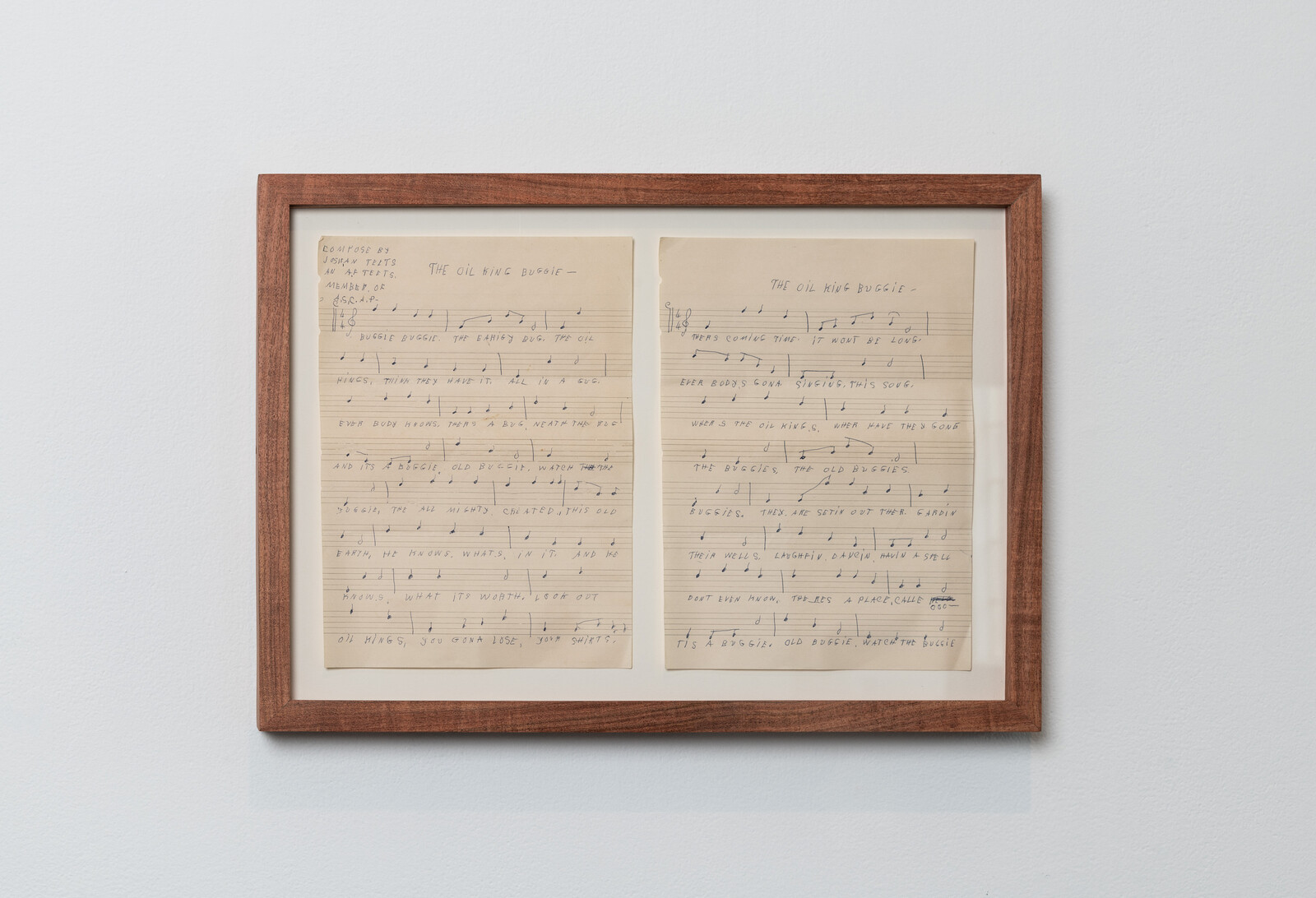

In a transgenerational dialogue the curator’s great-grandmother, Josie Ann Teets, an amateur songwriter, meets a young French artist. Josie Ann wrote and published The Oil King Buggie in 1975. The show contains a notation page, with words to the song curiously jumping under the lines, and spellings contorted to imitate a Texas accent. It’s a satirical take on the oil entrepreneurs’ hustle, reminding them that only the “all mighty” knows what’s in the Earth that He created. Two pieces by Clémence de La Tour du Pin, installed directly opposite the song, were made specifically for the exhibition. In the first, Arrangement VII: Der Parasit (all works 2023 unless otherwise stated), a mock-up of the German-language version of Michel Serres’s titular 1980 book, is displayed alongside archive photographs of Houston’s oil industry and the artist’s personal effects. The second, Arrangement IX: Peculiar Sweet Matter, presents a selection of beeswax casts of perfume bottles in petroleum black; they emit an agreeable odor evident only after leaning in to read the work’s label.

Anthropologists of infrastructure sometimes note that their subject is only visible when it stops working. Conversely, when infrastructure is pointed out, we see nothing but it, and all that’s considered invisible becomes a “space of representation.” Iris Touliatou turns the museum inside out: she presents an installation of staff calendars, complete with notes and deadlines, relocated from private offices into the gallery; these calendars are replaced, in return, by new office equipment purchased by the artist using her fee. This conceptual gesture connects the infrastructure of exhibition-making to the visitor experience in a profound way.

The inversion continues with another of Touliatou’s sleights of hand. When you book a tour, you’re let in the offices to look at A Model of the Dog of Alcibiades (c. 1800), a Museum of Fine Arts item purchased by the Blaffer Foundation, set up by the venue’s founder Sarah Campbell Blaffer. An extra level of history that Touliatou hints at is the foundation’s attempt, in 1999, to buy the earliest depiction of the animal, a Roman marble copy after a Hellenistic bronze, from a British collector. The bid was thwarted by a nationwide effort to keep it in the British Museum. Evoking the transatlantic competition over an artifact that is part of neither bidder’s heritage, Touliatou questions the supposed efficacy of the museum’s attempts to conceal ownership and transform it into a supposedly common good.

Objects that the museum infrastructure is supposed to protect and maintain again subvert the logic of the show. In works by Lonnie Holley, ektor garcia, and Benvenuto Chavajay Ixtetelá, the artists reference alternative, pre-railroad forms of connection. Holley’s The Skin That We Are Deeply Wrapped Within (2021) is a quilt with floating female profiles spray-painted over it. Guatemala-born Benvenuto Chavajay Ixtetelá is represented by a photograph of his performance in the sacred mountains of his native country, his body covered in leafage to signify an ascent to the state of “plant humanity.” Traditional Mexican doily-making informs the delicate copper screens and objects by ektor garcia.

These works form part of wider efforts within art to reinvent traditions in opposition to infrastructures of extraction. Pale Clay (Unknown Grid 8) (2022), by University of Houston sculpture professor Anna Mayer, complicates the self-evident conflict between the practices inherited through the matrilineal inheritance and the systems that discipline the institutions we are part of. Taking her deceased mother’s knitting patterns, based on works by Paul Klee, Mayer latch-hooks them and inks the tips of yarn, turning a textile piece into a mop-like object that points to domestic labor. Here, family infrastructure is entwined with the notions of inheritance and cultural work in a way that makes one question whether all infrastructures are, indeed, affective. How is the oil-veined Leviathan of the city related to one’s flesh and blood?

Finally, there are pieces that mock the mundane technicalities of the systems that surround us, accentuating the human touch. Gwenneth Boelens’s This Dusk Song (subtle body) transmits copper wire and reflective yarn through the upper parts of the exhibition space’s walls with spindles, rollers, and pulleys reclaimed from an abandoned textile factory. This apparatus’s activity is a mere metaphor—unlike Kate Newby’s series of Texas-made cast-iron grates installed at different drainage locations around the museum. Regardless of their functionality, these pieces feel closest to the curator’s position as the engineer of this narrative.

It is apt that Serres’s The Parasite is present in the show, if only as a mock-up. “The parasite,” Serres writes , “is an exciter. Far from transforming a system, changing its nature, its from, its elements, its relations and its pathways […] the parasite makes it change states differentially.”2 By claiming so many directions that the notion of infrastructure can take, “Intimate confession” might inspire visitors to differentiate between the false consciousness of comfort and the work that needs to be done to sustain it.

See, for example, Ara Wilson’s “The Infrastructure of Intimacy,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society vol. 41, no. 2 (Winter 2016): 247–280, which examines the sexual politics of the restroom binary; that is, how the separation of sexes influences and constrains erotic drives.

Michel Serres, The Parasite trans. Lawrence R. Schehr (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982), 191.