To the extent that repetition signifies a failure to progress, it is anathema to our industrious modern society. Yet the word embodies a paradox: in every iteration there is a difference, if only because it occurs in a different moment, a movement forward in time and space. Repetition gives us another chance. The group show “Repetitions”—featuring artworks by Nikos Alexiou, Beppe Caturegli, Panos Charalambous, Thalia Chioti, Maria Ikonomopoulou, Alekos Kyrarinis, Christina Mitrentse, Nina Papaconstantinou, Nikos Podias, Efi Spyrou, and Myrto Xanthopoulou—presents meditations on the theme.

The repetetive manual processes involved in the making of some of these works seem to express transformations more spiritual than physical, detected visually, if at all, in barely perceptible marks on the surfaces or slight irregularities in form. Nikos Podias’s Fragment (2022) is a delicate lattice constructed of fragile found papers such as teabags, with stains derived from rose petals and black tea evoking the “blood, sweat, and tears” commonly attributed to acts of painstaking creation. The even more ephemeral Black Curtain (2007–8), a delicate structure of reeds, paper, and string by the late Nikos Alexiou suspended on the wall nearby, is a tense yet tenuous membrane that seems to hover on the thresholds of light and dark, life and death.

Nina Papaconstantinou transcribes classic literary works in the manner of a medieval scribe, using carbon paper to impose the lines one atop another on a single page. The result is a dense, mesmerizing accumulation of script that is more image than text, its inky layers invoking the narratives as physical gestures and, in turn, chronological time as a clamorous congregation. The looping letters of M. Duras, The Man Sitting in the Corridor (2011)—where a few intelligible phrases break free in an occasional empty white space—recall the calligraphy of a culture long vanished. Homer: Iliad, Rhapsody 22 (White) (2019) documents instead the spaces in between the words, its red marks resembling the heartbeats recorded by an ECG: here, sensation seems to overpower language.

Daily routine can be boring, or a source of constant wonder—if you read between the lines. For her two works, from the series “Akrokerama” (2022), Christina Mitrentse has refashioned embroidery magazines from the 1960s and ’70s into whimsical sculptures shaped like the traditional Greek roof ornaments they are named after, conversing with their materiality as objects rather than the written contents by folding the pages one by one while painting and drawing over the pattern illustrations.

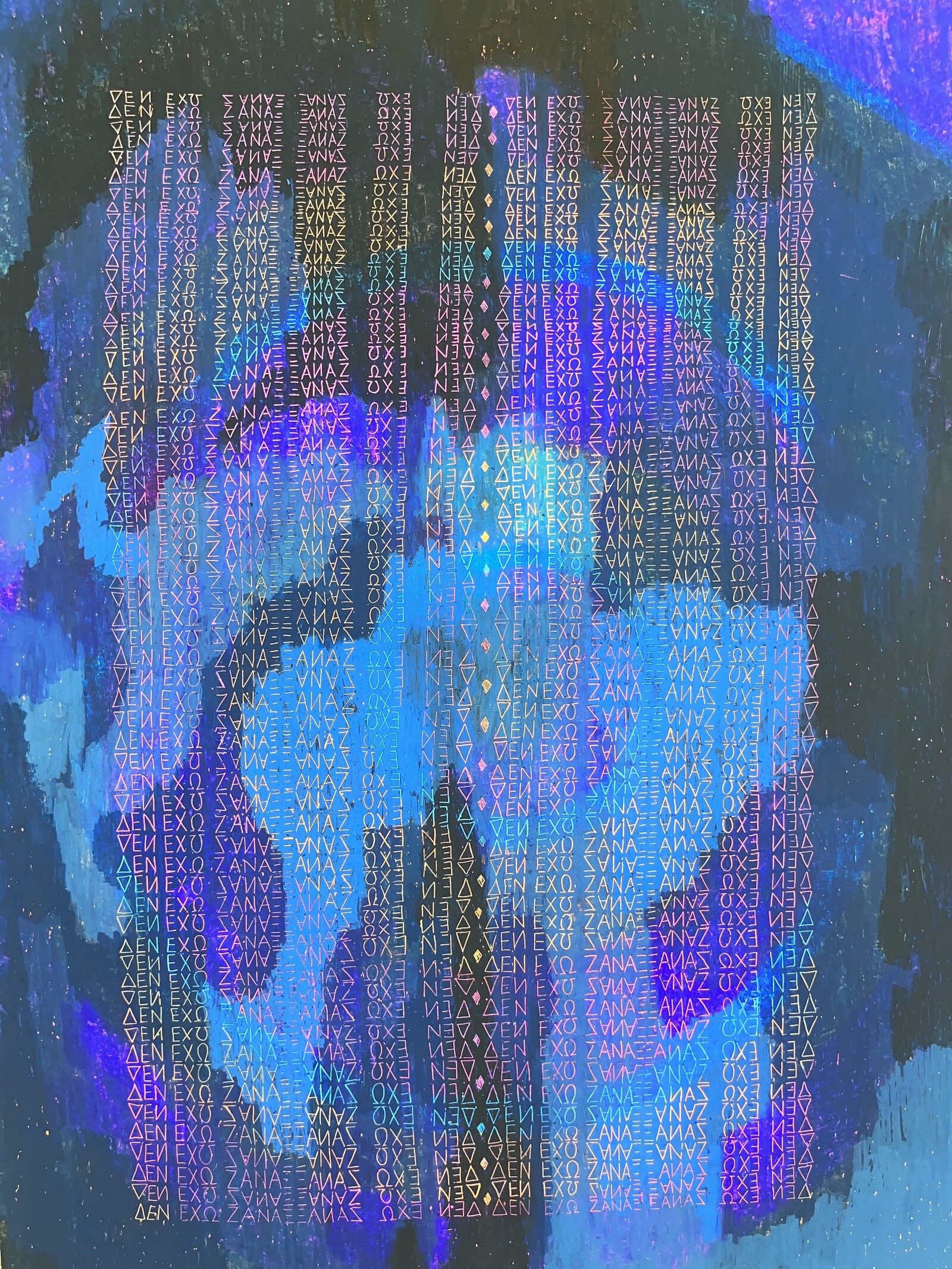

Repetition imposes order on the chaos of the cosmos—such as when we confine time in years, seasons, days, hours, minutes, and seconds. In her work, Myrto Xanthopoulou repeats phrases until they shed their conventional meaning to become mantras, highlighting both the urgency and the futility of words. In the painting I don’t have Xanax (2023) the Greek title, ΔΕΝ ΕΧΩ ZΑΝΑΧ, is scratched into the surface through the layers of oil pigment in columns of uniform capital letters that suggest an epitaph inscribed on an ancient tablet. Levitating on a field of deep blues verging on figuration, like a Rorschach test, the sentence is alternately mirrored and turned upside down so it can be read from every direction. Yet the lament, repeated until it drowns out all else, may also solicit a fear of Xanax: What if too much happiness dulls my senses, taking away the singular pathos that defines my (obsessive) personality? The letters in Blown Fuse (2023), by contrast, whorl into a senseless jumble of scribbles at the center of a luminous splotch of pinky peach against a shiny black ground. Here, they suggest an attempt to stave off inevitable disappearance with furious activity.

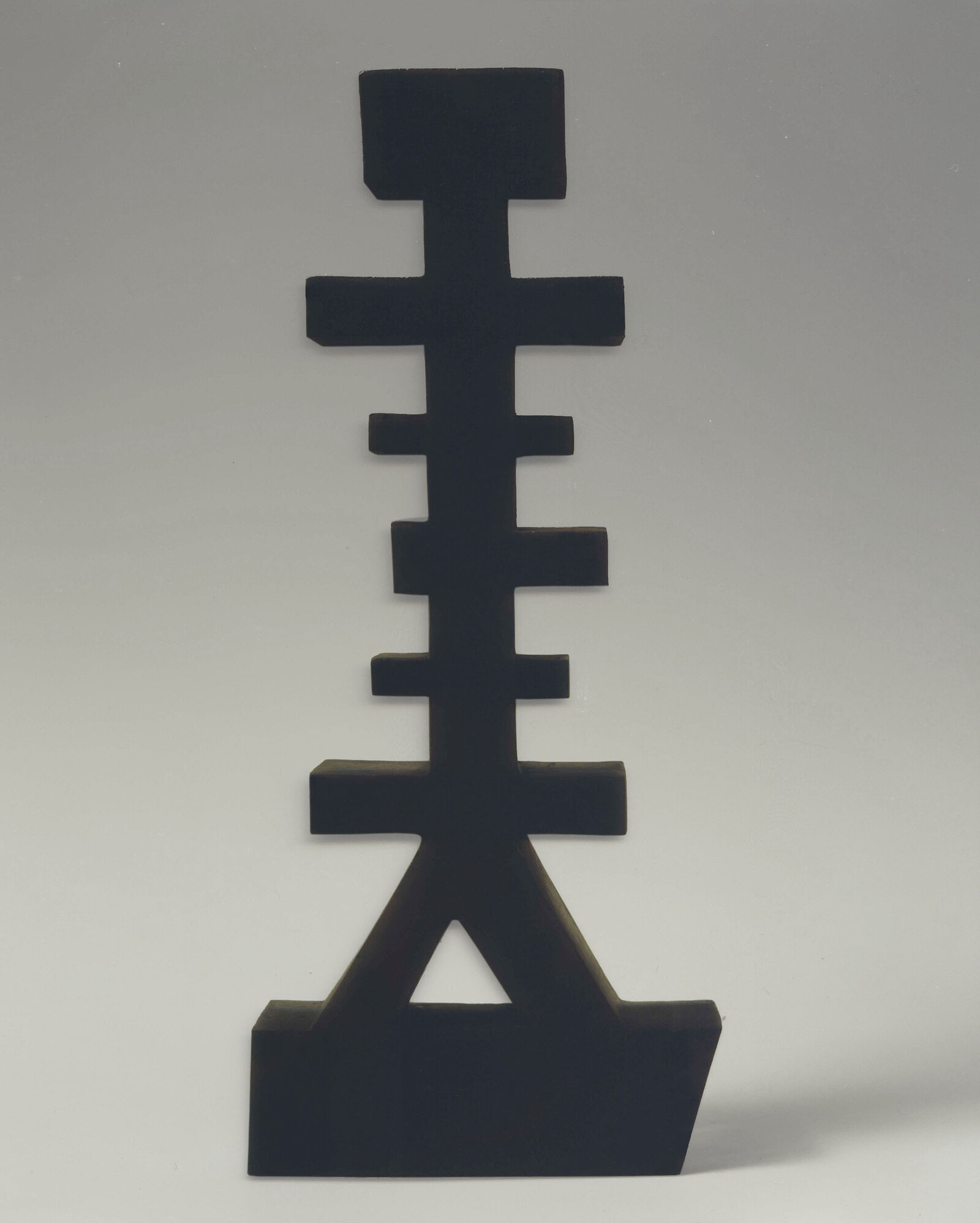

Underlying repetition is the fear of nothing. Artist Efi Spyrou embraces the void in the guise of monster alter egos, called TERANTIDS (2021–22), created with yellow reflective strips woven into a warp of black. Although they conjure coded patterns floating in a digital matrix, on the verge of vanishing into negative space, the creatures communicate a playful joy that seems human—conveying, perhaps, the possibility of coexisting with the Other as well as straddling physical and virtual realities. Beppe Caturegli’s five anthropomorphic sculptures (CF, 1990–93), lined up along a surface opposite, evoke the movements of performers dancing in a tribal ceremony. Made of terracotta painted black, the sleek geometric forms combine the sensibility of modern industrial design with African vernacular, integrating the celebratory with the quotidian.

Repetition promotes both change and stability, erosion and growth, in a never-ending feedback loop. A companion installation at the Poros Archaeological Museum, titled “On the Tomb [’Επὶ τύμβῳ],” comprises paintings and sculptures by Alekos Kyrarinis displayed among the ancient artifacts. Rendered in traditional egg tempera on wood, the imagery and flat perspective of the paintings recall the idiom of Byzantine iconography, where the skill is to copy ad infinitum. But the contemporary subjects are immersed in decidedly modern dynamic geometries, often nearly engulfed in abstraction, that induce a sense of animation and immediacy. Their presence awakens the antiquities, as if to say history is really just one long day: a dog carved in relief some 3,000 years ago, for example, looks as if it might leap out barking from the stone at a moment’s notice.

Repetition defines the perennial cycle of rites, customs, and celebrations that constitute a community. Process is the point: the ebb and flow of existence, never quite contained or defined. A herd of nearly identical horned animals from Mycenaean Greece arrayed in a vitrine—part of the Archaeological Museum’s permanent display—bears traces of the hands that fashioned and painted the clay thousands of years ago. The works in this show convey a similar intimacy, mystery, and collective experience, if one takes the time to see without looking too hard, as if emerging from a dark place into the light.