A diminutive and oddly classical homage to the eponymous character in Ridley Scott’s 1979 classic horror film Alien, entitled Bolaji resting between two takes (2023), is tucked into one corner of the front room of Anne Barrault’s gallery in Paris. The painting is small, the facture thick, with a palette in shades of white. The composition’s contrast is rendered in a warm maroon tone that reminds me of blood coagulating at the edges of a flesh wound. Despite this latent suggestion of violence, Franco-Tunisian artist Neïla Czermak Ichti’s portrait of the infamous being eschews the sexualized viciousness of its on-screen presence. Seated on a cheap plywood block, visibly marked by use, with its massive head resting on long, thin forearms, the alien just looks tired, like a construction worker on a fifteen-minute break.

Czermak Ichti became obsessed with Bolaji Badejo, the twenty-five-year-old Nigerian art student inside Ridley’s oppressive latex costume. She based the painting on one of only a handful of production photographs of the costumed actor between shots. Badejo was born in Lagos in 1953, immigrated to Ethiopia with his family in the aftermath of the Nigerian civil war (1967–70) and then to the UK. The one-time movie star had no previous acting experience. He was tall and thin enough to fit inside the costume and trained in tai chi after casting, which enhanced his natural grace and agility; he appears on screen possessed of a striking intelligence, despite the absence of spoken lines.

“I felt a sharp twinge,” Czermak Ichti writes in a 2021 catalog essay, “when I realized that [Badejo] hadn’t been credited with the other actors but alongside the stunt team, the voice of the computer, and the cat and its training team.”1 Czermak Ichti’s oeuvre is marked by her protest against forms of dehumanization, exemplified by Badejo’s story. But what fascinates me in the range of movie characters presented in “J’adore vous faire rire” [I love to make you laugh]—including Carrie from Brian De Palma’s eponymous 1976 film, zombies with their faces stitched back together, iridescent people with bright yellow and green skin tones—is that her work does not deny the violence done to these otherworldly figures, nor is that violence spectacularized. Drawn and painted with neo-Gothic humor, her characters destabilize normativity by teetering gleefully on the edge of human subjectivity and objectification.

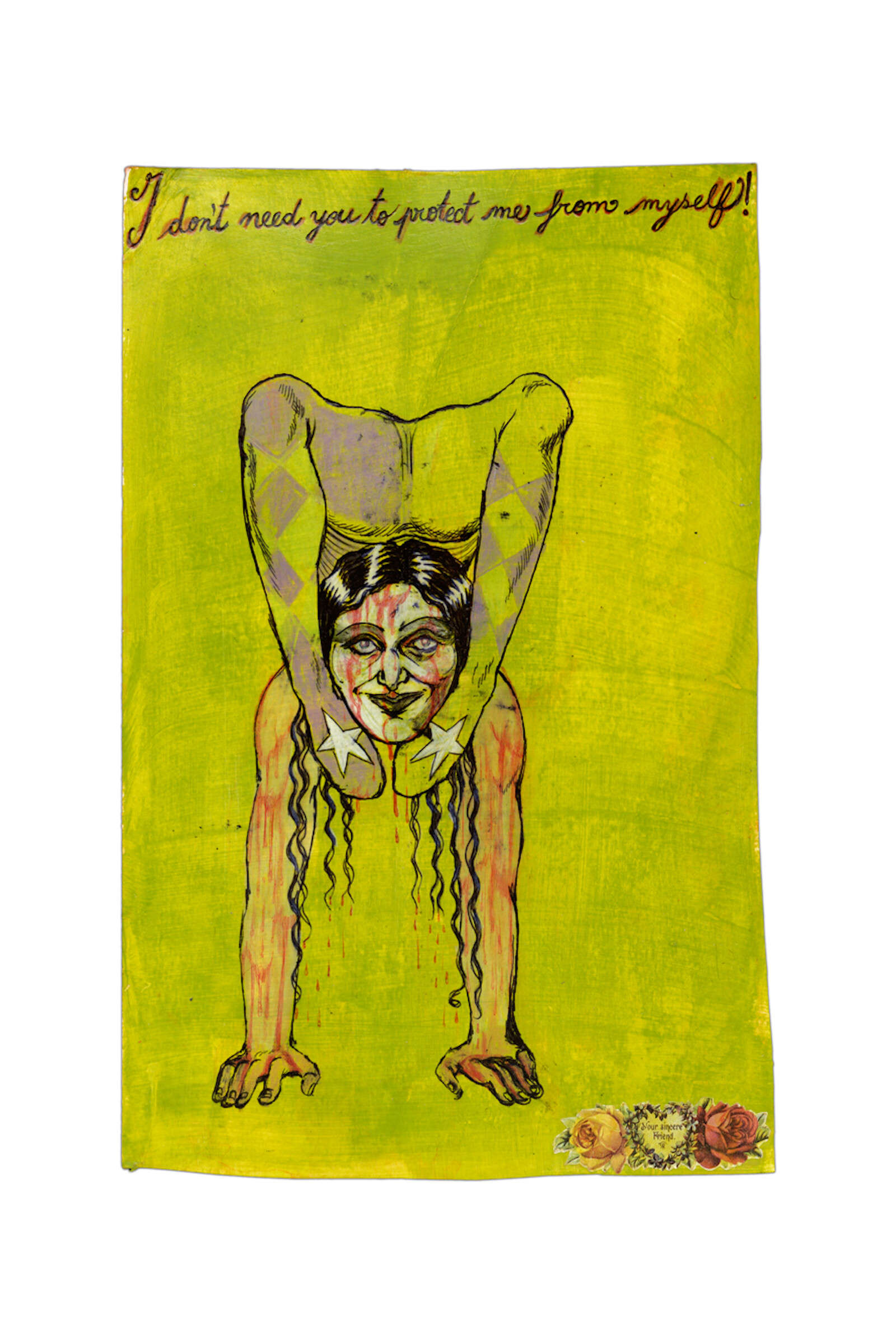

I don’t need you to protect me from myself! (2022) is an acrylic-and-ink drawing and collage on cardboard washed in a deep shade of lime green depicting a gender-neutral torso stacked atop a pair of outstretched arms, their palms planted on an imaginary ground. Rivulets of blood course down them. The not-quite-body is cradling a woman’s smiling head where its groin should (might?) be, her hair and face also dripping blood. In the bottom right-hand corner, a Victorian floral decoration frames the message “Your Sincere Friend,” contradicting both the tone of the work’s title, which is scrawled across the top of its cardboard ground, and the painting’s gruesome central figure. It renders a surreal acceptance of internal conflict—of the amputations one must inflict on oneself to survive—while also lightly mocking that same capitulation.

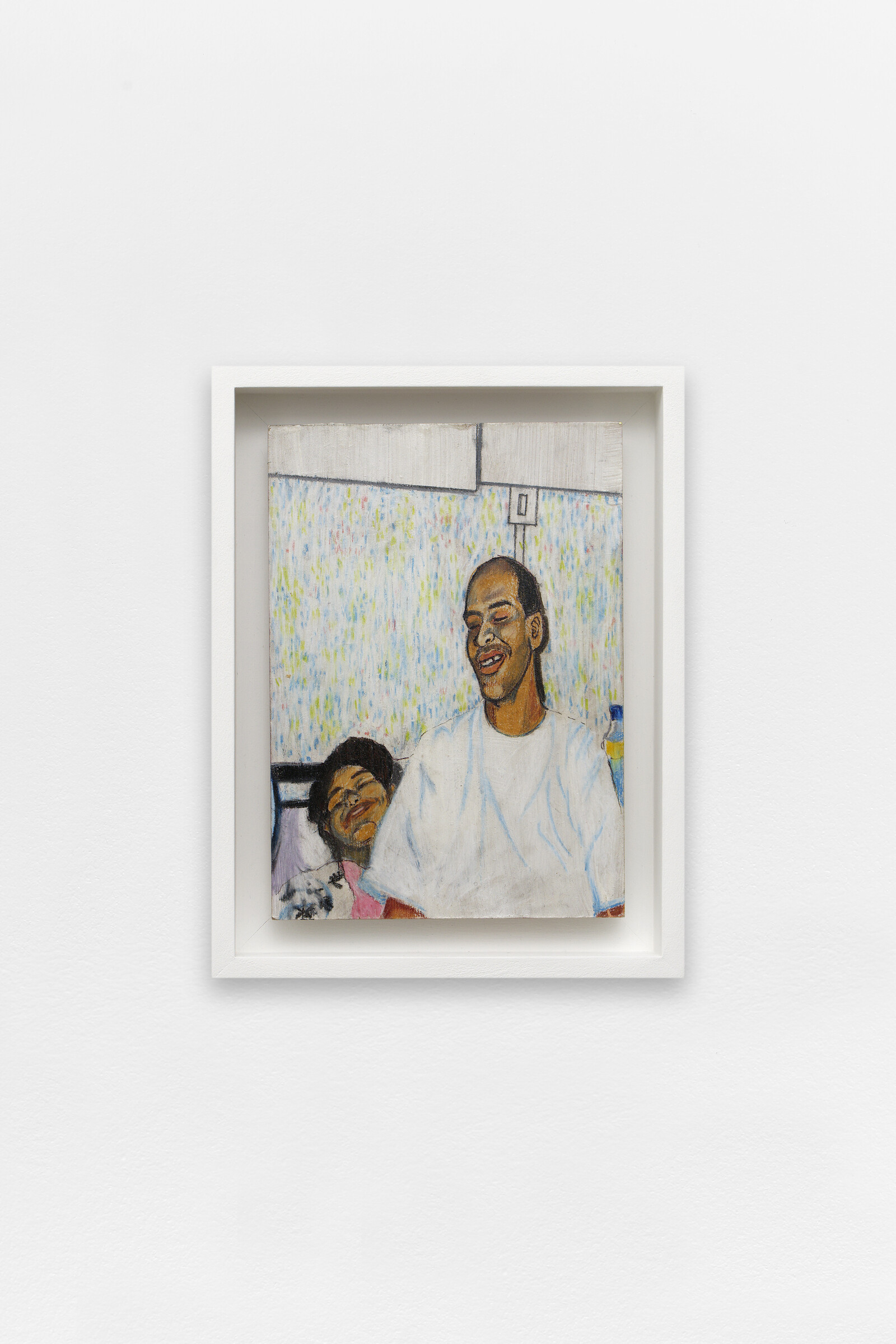

Brahim et maman, hôpital Jean Verdier, Bondy Nord, 9 juin 96 (2023), and So much fun (2023) function as a pair bracketing the same affect—which I will call “fuck it, let’s enjoy the feeling of being forced to rip ourselves apart as it all burns to the ground”—in very different graphic tones. The first is a painting of a snapshot made with the formal sincerity of Czermak Ichti’s homage to Badejo. The work shows a woman (the artist’s mother) and a man (presumably a relative) facing the viewer from a hospital bed, both caught with their eyes closed and smiling. In the second work, painted with acrylic on wood, the decapitated yet animated head of a woman is positioned on a florid purple ground next to an anthropomorphic cat. Both are painted in bright blue, both wear an expression of uncanny, beatific joy. The pair of works is saturated with a deep contradiction between the elation found in the margins (of the city, of active life, or of humanity) and the everyday viciousness that renders some people vulnerable to structural violence.

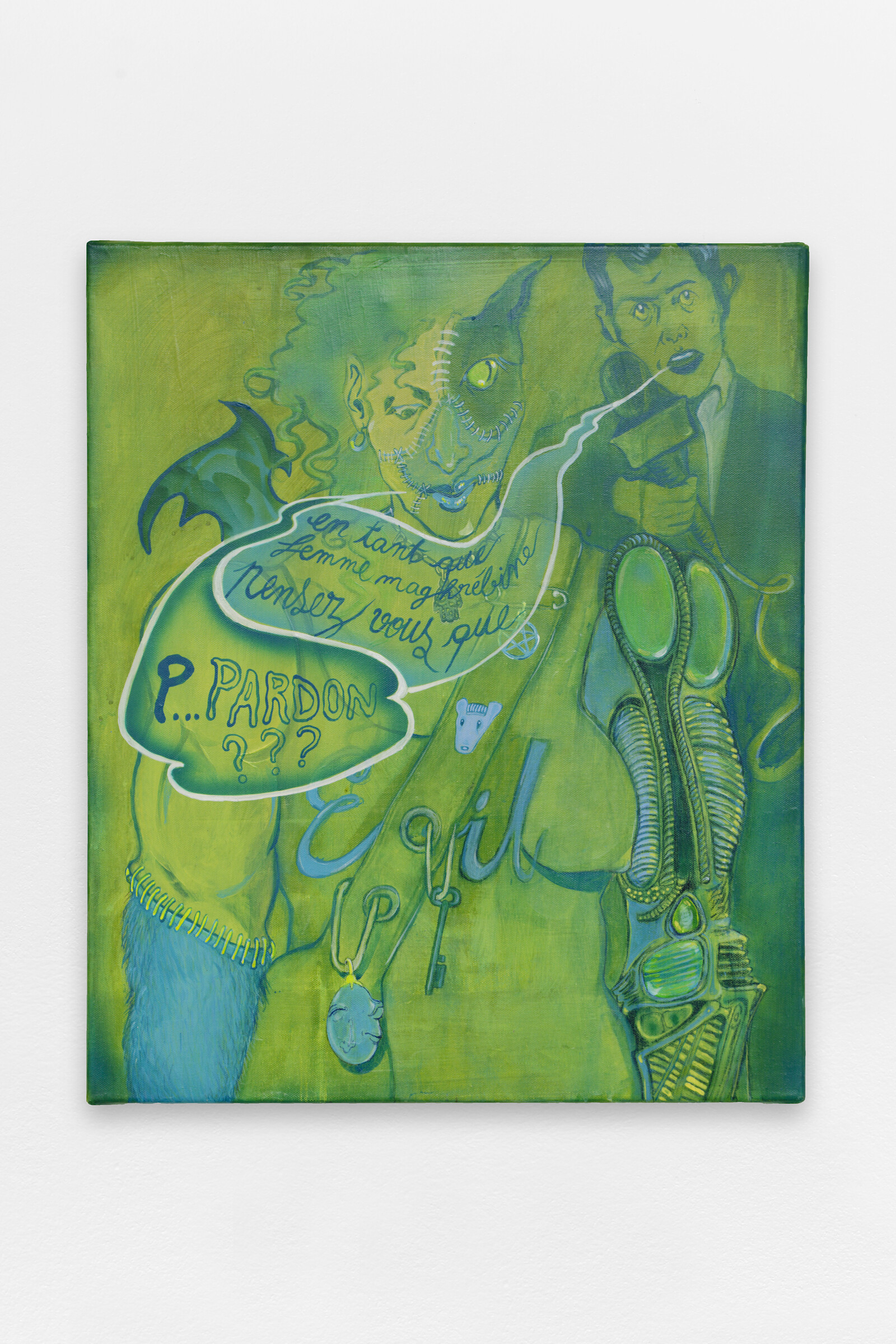

In Interviewed Monster wearing some fancy Japanese brand (2023) a self-portrait of the artist with a Frankenstein’s monster-esque patchwork of skin and small dragon’s wings unfurling behind her responds to a man in a suit who asks in a speech bubble, “As a North African woman, don’t you think that…” with outraged incredulity: “PARDON??!?!?”. Directly targeting the art-world’s racism, Czermak Ichti speaks from within its wake, to borrow Christina Sharpe’s formulation, or, from within the cinematic and narrative genres produced to represent the people who survive dehumanization enacted by white supremacy.

Neïla Czermak Ichti, Repos à nos magiques (Marseille: éditions P, 2021), 44.