In artist Sanya Kantarovsky’s latest curatorial venture, an exhibition at Metro Pictures organized around the underappreciated Dutch painter René Daniëls, he continues to examine the mechanics of artistic positioning. Similarly, in his previous curated exhibition, “No Joke” at Tanya Leighton (Berlin, 2015), he grouped together work that, through humor and self-deprecation, cast a self-reflexive eye on the mythologization of the artist.

Daniëls, who suffered a cerebral hemorrhage in 1987 at the age of 37, and has only made work sporadically since, was initially received as a Neo-Expressionist, a movement known more for the expulsion of sweat and blood onto canvas than critique of the broader art field. Yet Daniëls’s work—and the present exhibition, whose title “Sputterances,” a portmanteau of sputter and utterance, derived from a poem written by the artist—suggests that this is hardly a neither/nor proposition, and that, rather, expression is tied to the mutual dependence of sense and nonsense, central to which is the question of the frame.

For “Sputterances,” Kantarovsky has assembled 22 artists, ranging from his peers, elder statespeople of figurative painting’s seemingly perpetual renewal, and historical figures both vaunted and obscure, alongside three works by Daniëls. It’s not immediately clear what unites these artists, much less around Daniëls—few, if any, have had a direct relationship with the artist, but all seem to share with Daniëls (and, it should be said, with Kantarovsky too) an interest in the moments where figuration exceeds itself and spills into abstraction. Rather than placing other artists’ work in a historical or conceptual lineage with Daniëls, “Sputterances” seeks to construct a transhistorical painting network on the basis of shared formal qualities and diverse modes of affiliation.

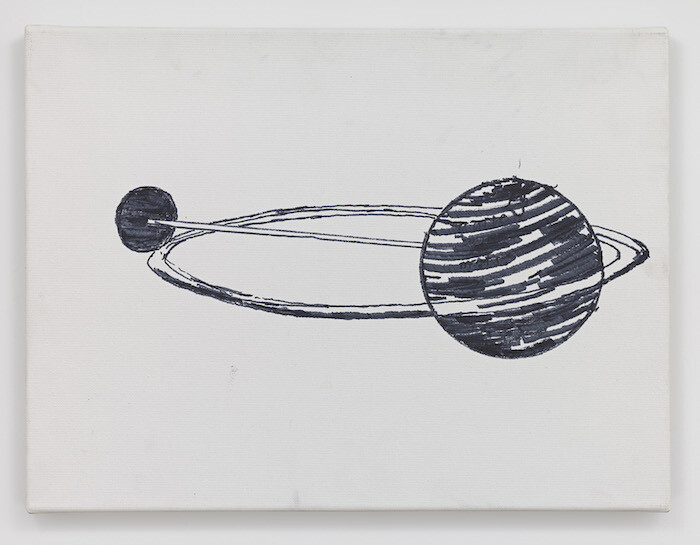

Formal resonances abound in this show, both across works in the exhibition and with Daniëls’s oeuvre as a whole. Celestial bodies, a persistent motif in Daniëls’s work following his stroke, are depicted here in his only work from this later period in the exhibition, 2006’s The Most Contemporary Picture Show, as well as in two more recent canvases by Mathew Cerletty (What’s the Feels Like?, 2017) and Walter Swennen (Wind Blue, 2015). The giraffes that occasionally appear in Daniëls’s paintings, redolent with themes of colonial expansion, are echoed in Leidy Churchman’s 2017 painting. Titled Free Delivery, it doesn’t look like the elder artist’s work so much as the three giraffes staring out at the viewer evoke its disorienting humor. A shared color palette of deep, earthy reds, blues, and greens leads to an unexpected synergy between the stunning nighttime tableau of Jacob Lawrence’s painting Christmas in Harlem (1937), and the moody abstraction of Monique Mouton’s St. Patrick (2016).

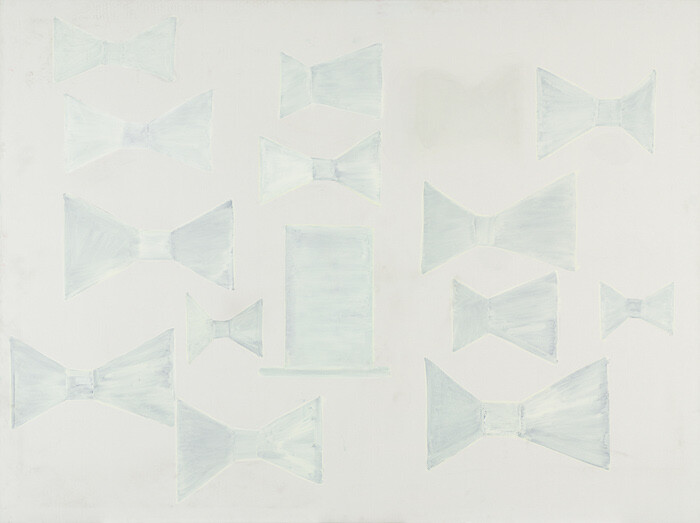

Besides Daniëls’s aforementioned painting, “Sputterances” contains two works completed in the initial phase of the artist’s career. The half-articulated forms of Hey verloren huis teruggevonden (The lost house found) (1982-83), where a wine glass seems to merge with a woman’s face amidst a sea of sickly green, collapse figure into ground and show the artist under the influence of surrealist automatism. More striking is Zonder titel (Untitled) (1987), part of a series of work in which Daniëls rigorously explored the art gallery as a kind of stage, insistently populating his canvases of this period with a mise en abyme-like diagramming of the white cube. Often, as in here, where they are set against a simple off-white background, these perspectival renderings of gallery walls are abstracted to form another immediately recognizable motif with its own rich set of performative connotations, the bowtie. Painting, this body of work seems to say, is at heart a theatrical practice. To return to an earlier question of framing, Daniëls’s painting isn’t expressive, but rather provides the parameters under which the artist can inhabit different modes of being. The present exhibition not only recontextualizes Daniëls’s work among painters who both preceded and followed him, but seeks also to bring a whole community into existence, however transitory it may be, through Kantarovsky’s own encounter with him.

The complex, internecine role of community in defining artistic practice speaks to larger issues around the critical viability of figurative painting today. Daniëls’s earlier work transpired at that crucial early 1980s moment in which the utopian micro-communities of punk gave way to a more familiar image of the art world as a globally interconnected network. In this respect, one of the exhibition’s most disarming works is by the late Karlo Kacharava (1964-1994), still relatively unknown outside his native Georgia, whose English Romanticism (1993) depicts a bohemian-looking couple walking through long grass, while the word “London” and a cartoonish tugboat float mysteriously above them. This allusion to a particularly English mode of pastoral romanticism perhaps belatedly anticipates the global marketing of subcultural style in which the art world functions as its well-oiled R&D wing. If Daniëls’s work performs critique by taking as its subject the constructions that make expression possible, it’s not clear that a curatorial conceit that promises to revitalize and broaden the artist’s milieu is capable of a comparable operation. Nonetheless, “Sputterances” is a refreshing exhibition, reminding the viewer that figurative painting can be a vehicle for critique, beyond mere recourse to its sociality.