Dakar’s elegantly dilapidated Ancien Palais de Justice hosts the Dak’Art Biennale for the second time. Inaugurated in 1958, the courthouse was closed to juridical business in 1992—coincidentally the year that Dak’Art was established. Officially signed over to Senegal’s Culture Ministry in 2017, the Old Courthouse is an architectural dream for art, with a cavernous central hall featuring an enormous open-air atrium presided over by a stately mango tree.

In “The Red Hour”—curator Simon Njami’s second edition of Dak’Art—the mango tree literally anchors the exhibition, with the floating shutters of Pascale Monnin’s Elevation Matthew (2016) tethered about its waist. Long strings hung with shutters painted blue spin out from the tree to form a suspended roof above the courtyard. These wooden window and door parts were salvaged from the artist’s home in Haiti, which was destroyed by Hurricane Matthew in October 2016. When shown in Dakar, Elevation Matthew extends beyond its Haitian origins to summon the devastations that have globally constituted the African diaspora—both historically, through slavery, and in the present day, via the direct and indirect forces of exodus. Offering a shared canopy beneath which disparate works are displayed, Elevation Matthew’s gesture of encompassment and inclusion reflects the curatorial approach of Dak’Art 2018, which gathers African art from across the continent and the diaspora. With contributions by 75 artists in its core exhibition alone, the Biennale is not so much a puzzle to be solved as a banquet to enjoy at one’s own will: if something is not to one’s taste, likely something just around the corner will be.

Surrounding the mango tree, temporary walls are scattered across the spacious central atrium, displaying photographs, sculptures, installations, and paintings. Some works, such as Téo Bétin’s installation 4th Floor Building (2017–18), called upon the space’s double-height scale, with its staircase standing as a monument to a remnant Salazar-era building in Maputo, during the Portuguese colonial occupation of Mozambique. The small maze of temporary walls allowed works to bask in the open air, the sunlight glinting off Frances Goodman’s relief of acrylic nails (Roiling Red, 2018) or the bare space afforded to Ermias Kifleyesus’s tightly knotted drawings Many Villages (2016) and Projected Sites and Institutions (2017), which features large white sheets sketched over with doodles from internet cafes that have been further worked into in the studio.

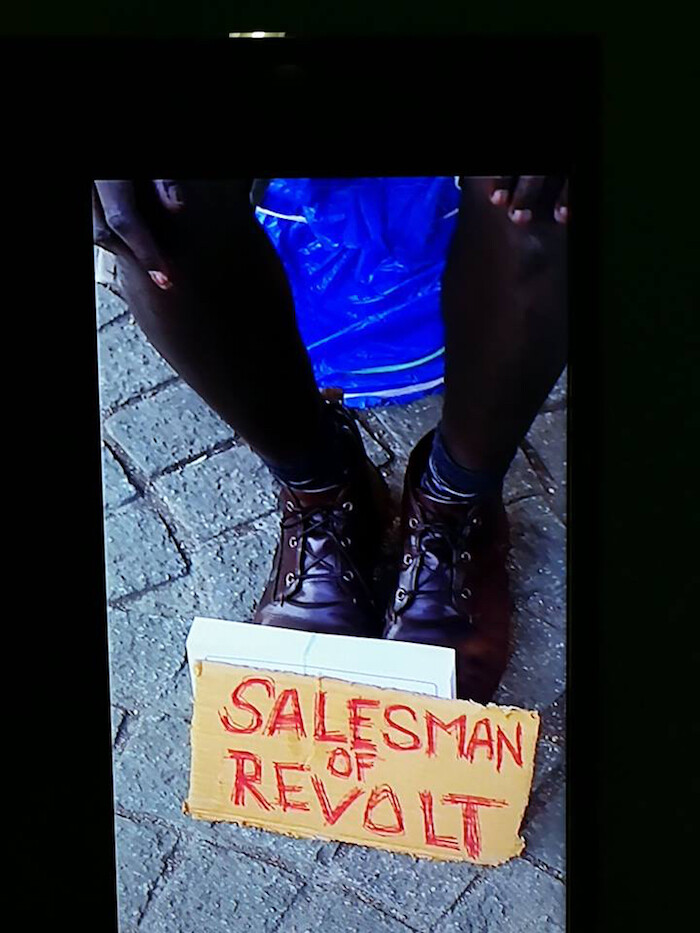

Rows of smaller offices along the courthouse’s perimeters allow for more intimate encounters with works, and host some of the show’s highlights. Kudzanai Chiurai’s video We Live in Silence (2017) drew audiences through its dense allegorical topographies, divided into eight parts. Chiurai is best known for his meticulous photographic tableaux and We Live in Silence is his first moving-image work. Whereas the still image can make static the tensions and contradictions of Chiurai’s glamorized counter-representations of African wealth and warfare, this complexity is fully unleashed in video. A mix of real-time and slow-motion footage allows Chiruai to lead viewers through layered, metaphoric compositions. In one scene, an opulent last supper is framed by up-turned cars and a shootout. Together with the infectiously sequenced and compressed beats of its soundtrack, this work will surely circulate well.

Another standout moving-image work is Loulou Cherinet’s striking and succinct video installation Axis (2018), presented in a long room fitted with a false wall that allows the illusion of a double projection. In three parallel parts, Axis sets off a giddy chain of pace and perspective, playing with the perceptions of time and image. To the left, an endless stream of newspapers flies across press conveyor belts; to the right, clouds are captured against a full moon or a setting sun. In between, a regimented cycle of European faces appears, lifted from unnamed historical oil paintings—all compiled to a neat six-minute loop with a gravelly, rumbling, staccato soundtrack.

In the long row of rooms adjacent to Axis, Paul Alden Mvoutoukoulou’s Medicine Blues (2018) offers perhaps the most direct—and most captivating—response to the Biennale’s subtitle, “A New Humanity.” In a room filled with large collaged panels, Medicine Blues opens with a nascent black figure ensconced in a cosmic egg rendered in the reflective foil of used pharmaceutical blister packs. These medicine packages are likewise puzzled together to form a triptych featuring the figure of a man, the Egyptian god Thoth, and another human figure, a biomedical man signed by the pharmacy symbol of the Bowl of Hygeia. Completing the installation is a giant clock that a present-day Sun Ra or Ziggy Startdust would surely covet.

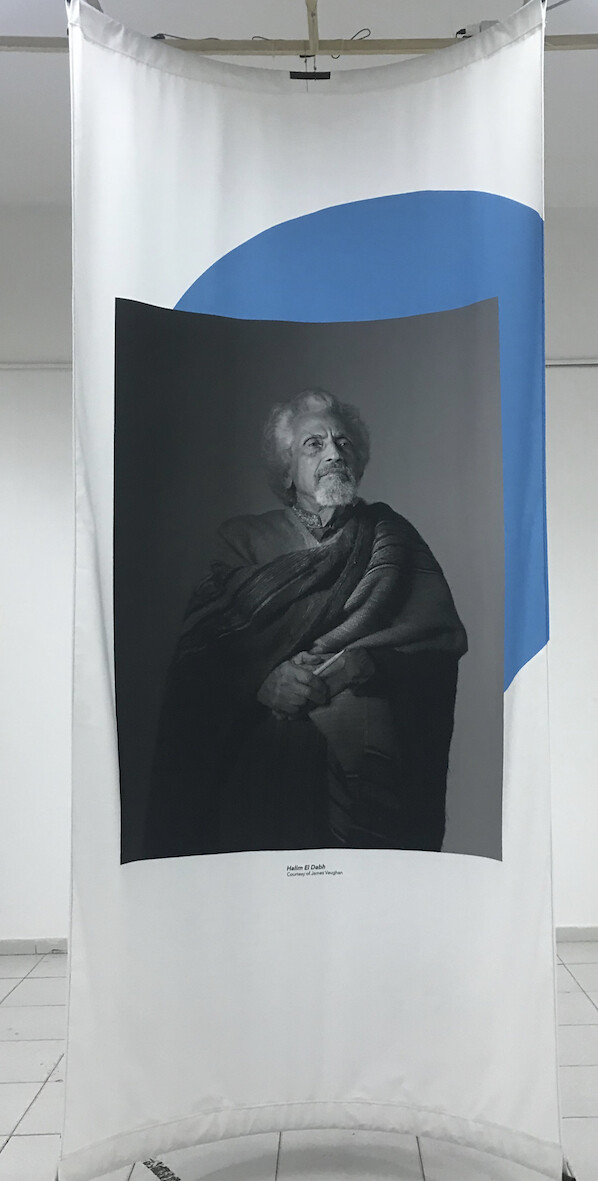

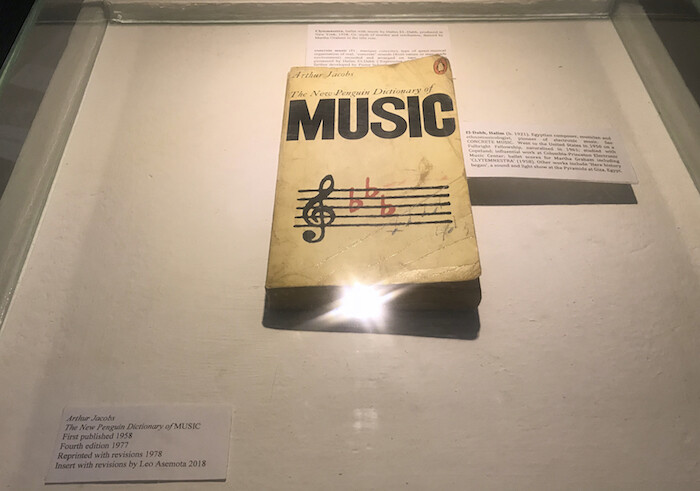

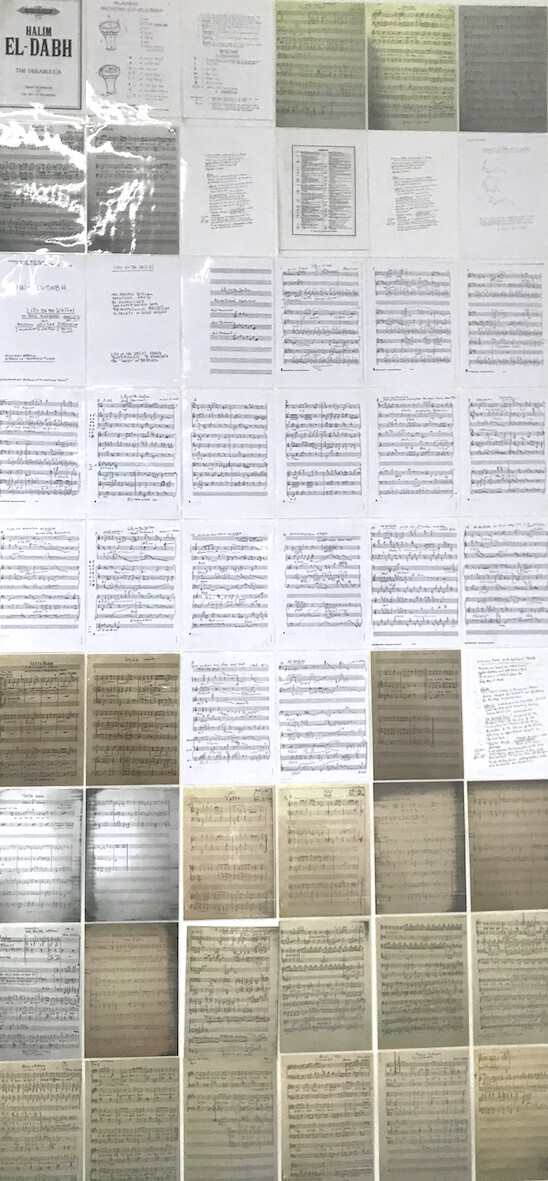

While the main exhibition took the temperature of contemporary African art on the continent and in the diaspora, a series of capsule presentations considered broader tangents and synergies farther afield. Housed at the Musée de l’Institut Fondamental d’Afrique Noire (IFAN), invited curators considered broader tangents farther afield. “Canine Wisdom for the Barking Dog”—Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung’s study of composer Halim El-Dabh (1921–2007)—spilled out across the IFAN grounds. Satch Hoyt’s Kush Yard Totem (2018), for example, extended to the fence-lines: part of the artist-musician’s ongoing “afro-sonic mapping” of acoustic transfer through the Middle passage. Three floating textile colonnades by Lorenzo Sandoval informed viewers of El-Dabh’s vast and impressive oeuvre across work on the “meanings of sounds, crossing the electric magnetic, and trans-sonority,” as mentioned in the exhibition’s catalogue, while Leo Asemota presented a canny and profound blank manuscript page collaged simply with the word “fidelity,” a part of his Two Workbooks for the Sonic Cosmologies of Halim El-Dabh (2018).

Upstairs, ParaSite director Cosmin Costinas and EVA International curator Inti Guerrero co-curated “The Long Green Lizard,” an impressive survey of extractive aesthetics and counter-practices in the Malay Archipelago and beyond. Simryn Gill’s haunting photographic studies of palm oil plantations Vegetation (Becoming Palm) (2016) were hung adjacent to Cian Dayrit’s vibrant and sobering tapestry Yuta Nagi Panaad (Promised Land) (2018), which colorfully maps present-day extractive violence in Mindanao, Philippines, and back-to-back with an incredible gem of Cuban cinema history—Nicolás Guillén Landrián’s film Coffea Arábiga (1968), which castigates the Afro-Cuban suffering caused by Fidel Castro’s industrialization of coffee plantations by comparing plant and human lesions.

In the same quarters, Clark House Bombay founder Sumeshwar Sharma turned his focus toward the domestic and intimate relations of diasporic spaces and nationalized domains in the exhibition “Family Function.” In it, Jihan el Tahri’s audio-visual memoir Diaspora FM (2018) charted a map of overheard and remembered soundtracks across the global south and north, while Hamedine Kane and Ayesha Hameed’s contribution, In the Shadow of our Ghosts (2018), included a sensitive and reflective video correspondence of contemporary migrant experience.

In the third part of the IFAN annex, Alya Sebti, Director of IFA Gallery in Berlin, stood steadfast in the present tense with the exhibition “Invisible,” staging a series of temporary darkened chambers, each with its own consideration of immediacy as a sensorial as well as temporal concern. With a strong focus on video and multimedia, the presentation brought together works such as Mohammed Laouli’s Hassad al Houb [Labor of Love] (2017), produced by speaking Silvia Federici’s 1975 manifesto on domestic work Wages Against Housework to small vials of rose water at their site of production in Morocco; Younes Baba Ali’s Daily Wrestling (2018), a welcome video reflection on the street life of Dakar that positioned viewers in a sand-pit stadium; and the video choreography of Anike Joyce Sadiq’s You never look at me from the place from which I see you (2015), which sat viewers in a chair amid the projection itself.

First mandated in 1989 as an alternating biennale of literature and visual arts, Dak’Art carries forward a vibrant pan-African tradition. The dedication of the Old Courthouse to the Culture Ministry could, with refurbishment, deliver Dakar a major contemporary art venue, and the effort of the Biennale to simultaneously establish infrastructure and stage a presentation cannot be mistaken. As visitors sped in taxis between the venues, paying 2000 or so West African francs a piece,1 it would be all too easy not to mind that the currency itself is a colonial hangover—one that requires its nations to deposit half their foreign exchange reserve at the French Treasury, while France writes up the interest it returns as development aid. Dak’Art is a biennale achieved in so many ways despite the weight of the neo-colonial yoke. What it lacks in infrastructure it gains twofold in the riches of the pan-African tradition, and in the warm-hearted and truly sophisticated setting of Dakar itself.

The West African Franc is fixed at 655.957 CFA francs to 1 euro, a condition favorable to French contractors but often disastrous to local governments that cannot adjust according to commodities market fluctuations.