April 23–November 27, 2022

Among the many dizzying contradictions that characterize the Venice Biennale is the persistence, amidst the rhetoric of decentering and decolonization, of a national pavilion format that gives prominence to those western powers considered a century ago to constitute the world order. The issues this raises are complicated, in this year’s edition, by apparently conflicting attitudes to the construction of identity (to be affirmed or broken down) and the violability of borders (to be defended or dissolved, sometimes within the same press release). For all of the anachronism and cognitive dissonance, one purpose of the Biennale’s pavilions might be to drag these contradictions—all of which have “real world” analogues or implications—into the light in order to discuss them.

With its façade transformed by hanging thatch into an homage to vernacular African architecture, Simone Leigh’s attention-grabbing US Pavilion is pointedly titled “Sovereignty.” As a counterpoint to Cecilia Alemani’s surrealist-infused international exhibition, which foregrounds fluidity and category slipping, this assertion of the right to self-determination is striking. The sheer physical presence and self-possession of sculptures indebted to African traditions—precisely and sparsely arranged through the pavilion—communicate an identity that is confident, coherent, and secure in its boundaries. Yet the title also draws attention to the fact that this celebration of African heritage is delivered by a sovereign American citizen under the auspices of the US Pavilion, offering another reminder of who is enabled to represent what in Venice.

The Nordic Pavilion, renamed for this edition as the Sámi Pavilion, states its intention to “celebrate the art and sovereignty of the Indigenous Sámi people.” The belated foregrounding of the Indigenous cultures of colonized countries has in recent editions of the Biennale more often felt like a gesture than a commitment, with the language of “giving” the space to a marginalized community revealing something of the attitudes behind the commission. Yet in this sympathetically light and airy space, the formally varied work of Pauliina Feodoroff, Máret Ánne Sara, and Anders Sunna is allowed to speak on its own behalf—without being shoehorned into a curatorial conceit, framed as “craft” or “folk” in order to distinguish it from a presumptively western “contemporary” art, or co-opted to launder a country’s image—to issues of land rights and guardianship. In the Polish Pavilion, meanwhile, Małgorzata Mirga-Tas’s immersive tapestry Re-enchanting the World (2022) upholds the artist’s right to participate in and repurpose work from other cultural traditions by replacing the Greek gods and Italian idylls of the celebrated Renaissance fresco in Palazzo Schifanoia with scenes from everyday Roma life. Running around the pavilion’s four walls, the patchwork insists that cultures and communities are preserved not by quarantining them from others but by seeking out mutually productive forms of cohabitation and exchange.

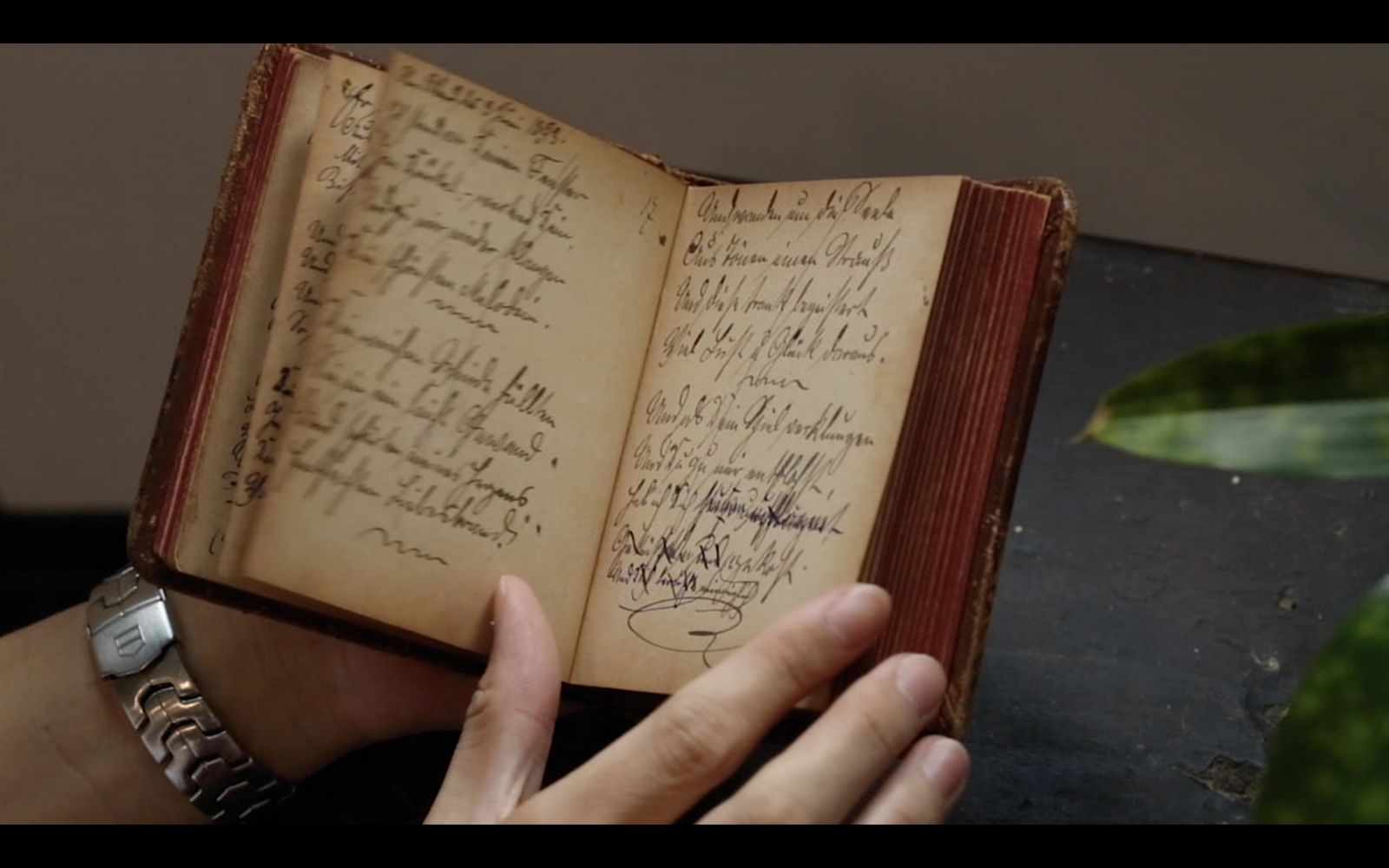

How it might be possible to create and maintain those conditions is one subject of Shubigi Rao’s exceptional contribution to the Singapore Pavilion, which shows the latest iteration of her decade-long investigation into the “book as a site of resistance.” Taking the form of a book that visitors can take away, a sweeping paper curtain onto which one of Rao’s typically elegant sentences has been printed, and a film of interviews, the presentation considers the processes of silencing and erasure—through, for example, book burning or banning—that make it possible for one community of people to countenance violence against another (or, for that matter, against other animals or the land). “Pulp” is a richly layered and brilliantly articulated call to defend the intellectual principles on which democratic society depends. It achieved the rare feat among national pavilions of feeling both startlingly timely and enduringly important.

Chief among the principles espoused by Rao, who has published and exhibited as a fictional polymath under the pseudonym of “S. Raoul,” is playfulness. If play enlivens a society by disrupting its conventions before they ossify into received wisdoms or repressions, then the prevailing absence of humor in this edition feels more like complacency or risk aversion than somber reflection on the disastrous state of the world. Zineb Sedira’s irrepressible French Pavilion is a glorious exception, giving the lie to the lazy assumption that art must be po-faced to be political. A love letter to the golden age of political cinema and a reflection on identity formation, “Les rêves n’ont pas de titre” [Dreams Have no Titles] transforms the French pavilion into something between a matryoshka doll, four-dimensional jigsaw puzzle, and jewelry box. A story told through a short documentary film in a cinema-style screening room at the rear of the building is refracted in the surrounding rooms into interlinking theatrical performances, installations, and sculptures. In the film, the artist speaks of her experience of cinema as a young girl as not only an escape from racism but as a way of imagining herself into roles outside those that society would impose on her. Creativity is figured, without stated object or political ends, as “a way of living, a way of resisting.” As outsiders of all stripes know, and Sedira’s intricately constructed shelter from the world confirms, art can serve as a refuge in which the alienated might meet and make common cause.

Francis Alÿs’s series of “Children’s Games” videos (1999–ongoing) illustrate how creativity can transform the trauma and chaos of the world into manageable systems. One of these documents shows how Mexican children have adapted the game of “tag” to their times, with the touched players transformed into red-mask-wearing carriers of the “contagio” that gives the new version its name. Besides giving the strong impression that kids are much better at inventing effective coping strategies than adults, the videos also point to the kind of imaginative transformations by which art can change our experience of the world.

How we see is the subject of Yuki Kihara’s “Paradise Camp” at the New Zealand Pavilion, which starts from the speculation that the models for Paul Gauguin’s infamous Polynesian paintings might actually have been members of the “third gender” Fa’afafine community of Samoa to which the artist belongs. Kihara translates her research into a series of gloriously irreverent and fabulously camp photographic re-enactments of Gauguin’s paintings complemented by a video in which a group of Fa’afafine argue about the breasts depicted in Two Tahitian Women (1899) while trading bitchy comments on each other’s costumes. In another video, the artist dresses up as Gauguin in order to tell him that she will be appropriating and “upcycling” his work. Kihara’s piece does not shy away from the consequences of othering representations—hanging in the corner of the room is a newspaper page reporting the suicide of a member of the community—but rather reclaims the production of fantasy as a strategy of resistance.

Among the national pavilions I don’t have space to write about here are numerous intelligent and affecting presentations, but the overwhelming impression is of fear of controversy. Pieties are more often reasserted than challenged, and the work’s disruptive potential too often ringfenced by the supporting literature. The most compelling pavilions are those that assert rather than deny the tensions—between escapism and engagement, self-affirmation and collective identity, reason and imagination—that underpin not only this Venice Biennale but the processes of artistic production.

Quinn Latimer’s review of the 59th Venice Biennale’s international exhibition, “The Milk of Dreams,” will be published on Monday.