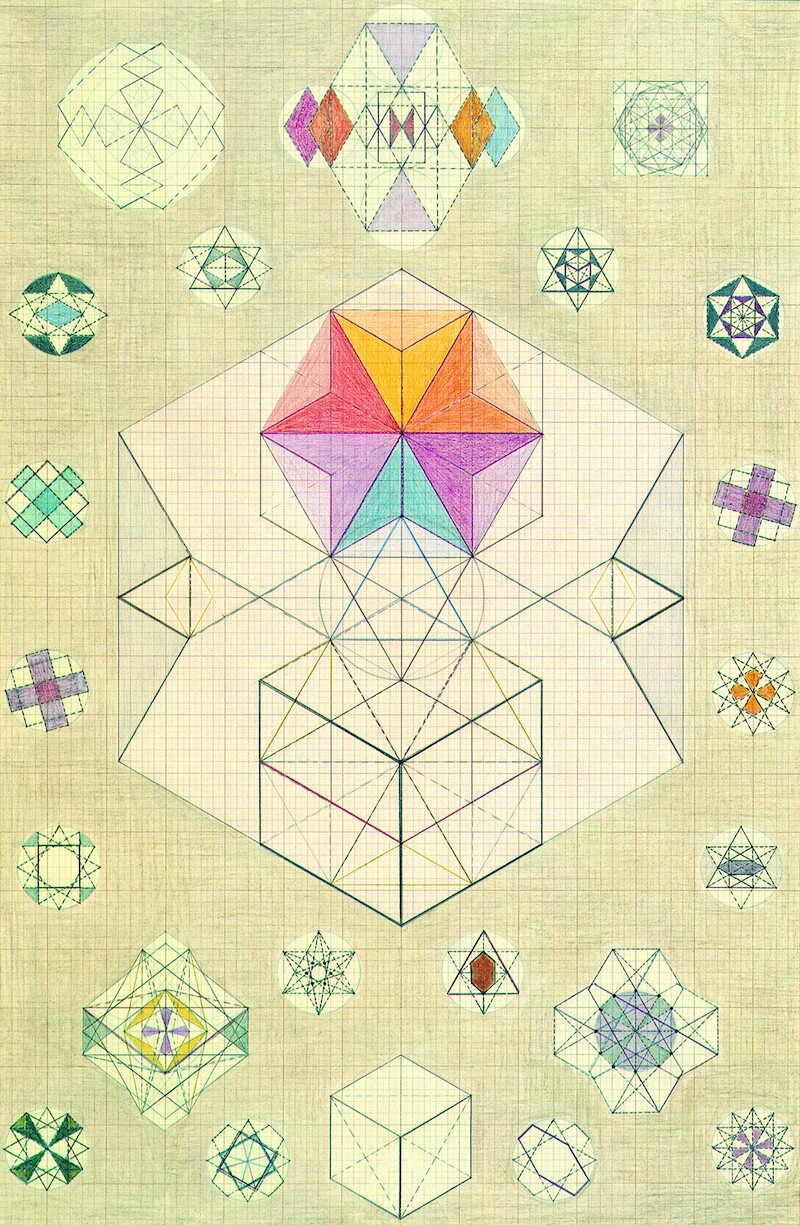

“Solar and logical / decadent and symmetrical / angels are mathematical.” Lyrics from Coil’s song “Fire of the Mind” (2005) come to me while I look at Emma Kunz’s gorgeous large-scale drawings. Kunz was a Swiss healer who began making these works in 1938, when she was 46. She had no formal artistic training, and the 500 or so drawings she made were never exhibited during her lifetime. For her, they were tools crafted as part of broader therapeutic and divinatory practices. Today they appear like a crew of decontextualized mathematical angels, as intense as they are inscrutable.

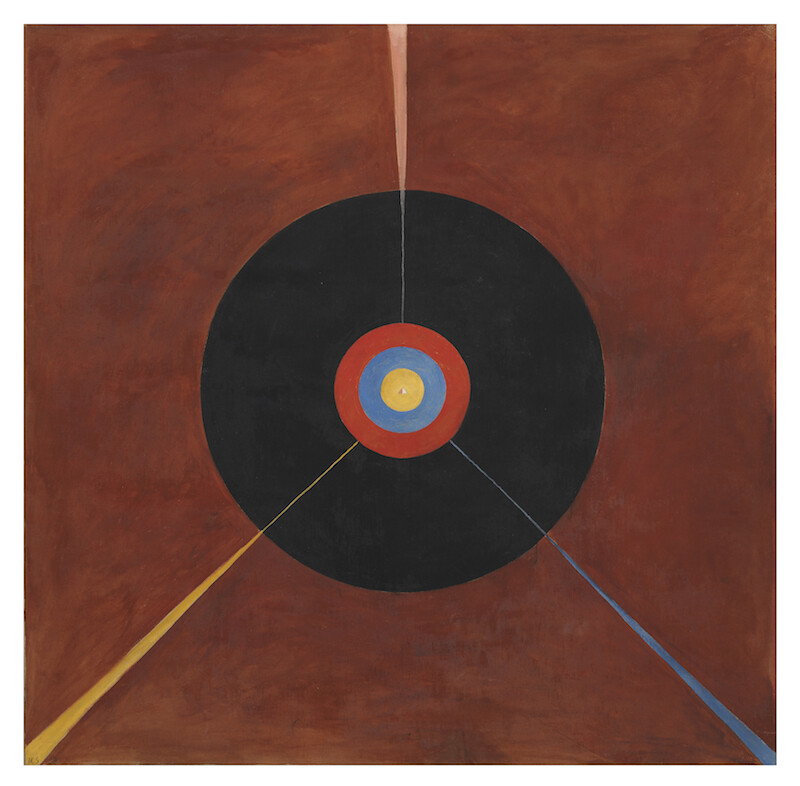

The exhibition “World Receivers” puts Kunz in the company of Hilma af Klint and Georgiana Houghton, two women who also developed abstract visual languages as part of their personal esoteric investigations—af Klint in Sweden in the first decades of the twentieth century, Houghton in England in the second half of the nineteenth. The three differ from one another in important respects, but there are intriguing commonalities, including the fact that all of them trouble the notion of autonomous authorship by posing that creating be understood as a matter of receiving. Describing her process, af Klint wrote: “The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings and with great force.”1 Houghton also claimed that when executing her “Spirit Drawings” (as she termed them), she had no preconceived idea of what was going to be produced, her hand being “entirely guided by Spirits.”2 In Kunz’s case, her inscriptions were guided by a pendulum, a tool she also used in her practice as a healer in order to map and direct energies that were external to her.

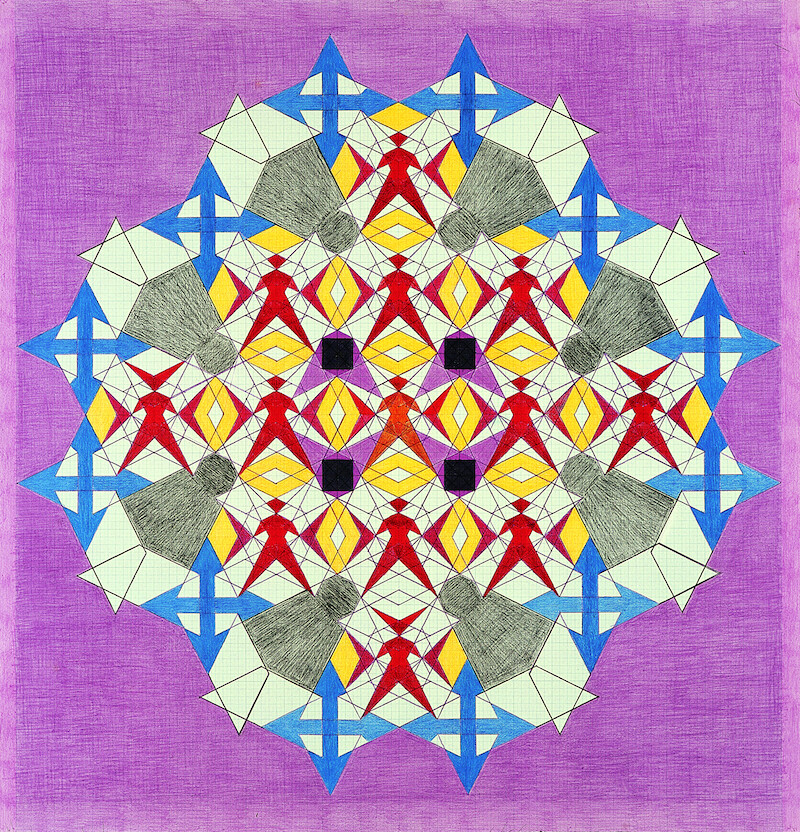

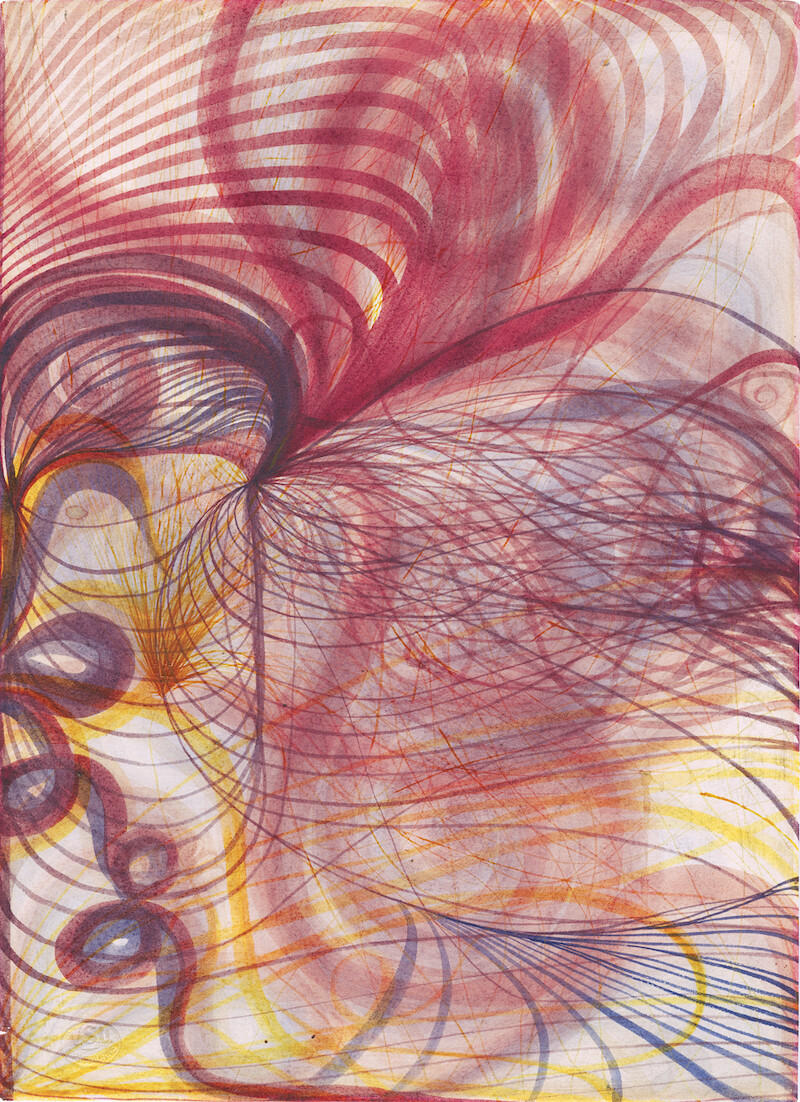

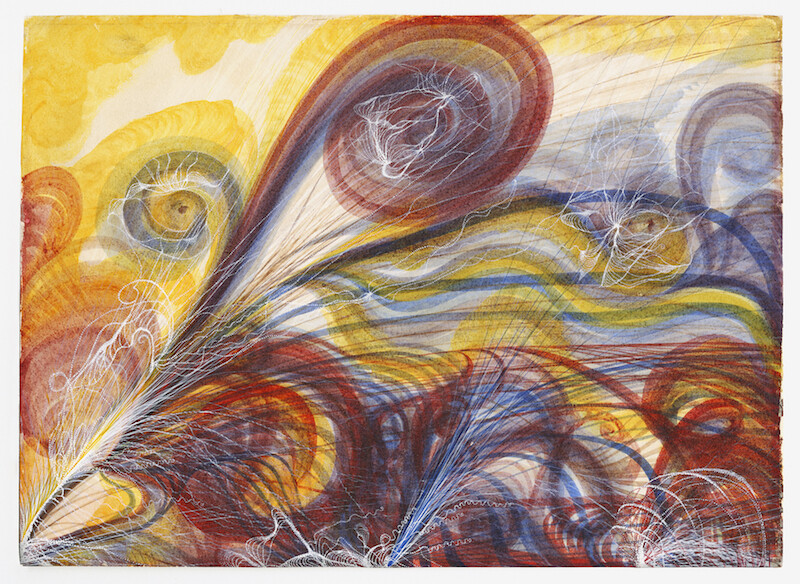

Visitors to the long, narrow hall of the Lenbachhaus’s subterranean Kunstbau gallery first see af Klint’s rhythmic and richly symbolic paintings, representing various phases in her long trajectory. Then there are Houghton’s proto-psychedelic watercolors, with many layers of undulating lines built up into dense blocks of energy. They’re displayed in frames in the middle of the room, with both sides of the page visible––allowing viewers to see the extensive notes she took on the backs of her works, recording details about the different spirits who helped execute them. Last are Kunz’s drawings, mostly wall-mounted, with a few displayed horizontally so they can be experienced from multiple angles.

Of these three historically overlooked artists, af Klint’s work has come to receive the most attention, with numerous major international shows in recent years, including her current exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, which has occasioned a swell of fascination and praise. The attention is deserved, and belated. Af Klint seems to have intuited that her paintings were ahead of their time, stipulating that they should not be made public until 20 years after her death in 1944. But even so, the continued exclusion of her work from art-historical accounts of modernist abstraction is scandalous. As recently as 2012, she was left out of a major survey at MoMA about the “invention” of abstraction, on the grounds that her paintings didn’t count as art.3

The oldest of the three, Haughton’s work also remained obscure longest. The “Spirit Drawings” are usually housed in a Spiritualist church in Melbourne, Australia, and a 2015 exhibition at the Monash University Museum of Art was the first time they were presented outside a Spiritualist context in nearly 150 years. Unlike af Klint and Kunz, Houghton had wanted her work to register with a contemporary art audience. She self-funded an exhibition in London in 1871, which was met with bafflement and indifference, leaving her with a huge financial loss. This was half a century before Kandinsky’s abstract paintings, which have so often been celebrated as the “first” to fully break with the Western tradition of figurative representation on the canvas.

What do we see when we look at these three artists together? It would be misleading to say that they are united by their esoteric interests, because these were completely heterogeneous and continually evolving, ranging from Spiritism to Rosicrucianism, Buddhism, Blavatskian Theosophy, Anthroposophy, Kabbalah, and beyond. What clearly unites them, however, is their absence, for so many decades, from the established narratives of canonical art history. While being presented in this exhibition with the invisibilities of energies, entities, or cosmic resonances, we’re also looking at another sort of invisibility: the long-standing invisibility of these women (and so many others) in art-historical discourse. For those who are attuned to that dimension, engaging with the history of art can become a practice akin to clairvoyance, where a sort of extrasensory perception is necessary to unveil the flawed logic of the writing of the canon. It isn’t just about making the familiar narrative more complete by filling in the gaps, it’s about letting those gaps reveal the insubstantiality of the whole premise of that narrative. Bring in the ghosts!

Cited in the exhibition catalogue, “World Receivers,” eds. Karin Althaus, Matthias Muhling, and Sebastian Schneider (Munich: Lenbachhaus, 2018), 87.

Georgiana Houghton, “Catalogue of the Spirit Drawings in Water Colours exhibited at the New British Gallery, Old Bond Street, by Miss Houghton, through whose mediumship they have been executed, May 22, 1871,” republished in “World Receivers,” 38–43; 40.

“Af Klint was not even a footnote in the recent show at MoMA in New York, ‘Inventing Abstraction, 1910–1925’: the show’s curator, Leah Dickerman, justified the artist’s exclusion because she is not convinced that Af Klint saw her paintings as art.” See Jennifer Higgie, “Hilma Af Klint (Review)” frieze 155 (May 2013). https://frieze.com/article/hilma-af-klint-0.