In the video documentation of Burial Pyramid (1974), Ana Mendieta’s body looks like it is lodged in the aftermath of a landslide. Lying on the ground, everything but her face covered with muddy rocks, the late artist seems trapped under the stones’ weight. She starts to breathe great heaving breaths and the rocks slowly shift and then tumble away. The soft flesh of her midriff and the areola of her right breast faintly come into view through the grain of the digitized Super 8mm film.

Mendieta’s film immediately drew me into “Soft and Wet,” a group show curated by Sadia Shirazi at the project space of the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts. It is shown across the room from the entrance and when I turn away from Mendieta’s immobilized form, I notice a pedestal by the door and return to inspect it. The slim, stapled booklet on it is a facsimile of the catalog of an exhibition curated by Mendieta, Kazuko Miyamoto, and Zarina at feminist gallery A.I.R. in New York in 1980. “Dialectics of Isolation: An Exhibition of Third World Women Artists of the United States” was organized in response to the marginalization of women of color within white feminist art circles in the 1970s. “This exhibition points not necessarily to the injustice or incapacity of a society that has not been willing to include us, but more towards a personal will to continue being ‘other,’” the final lines of its curatorial text read.

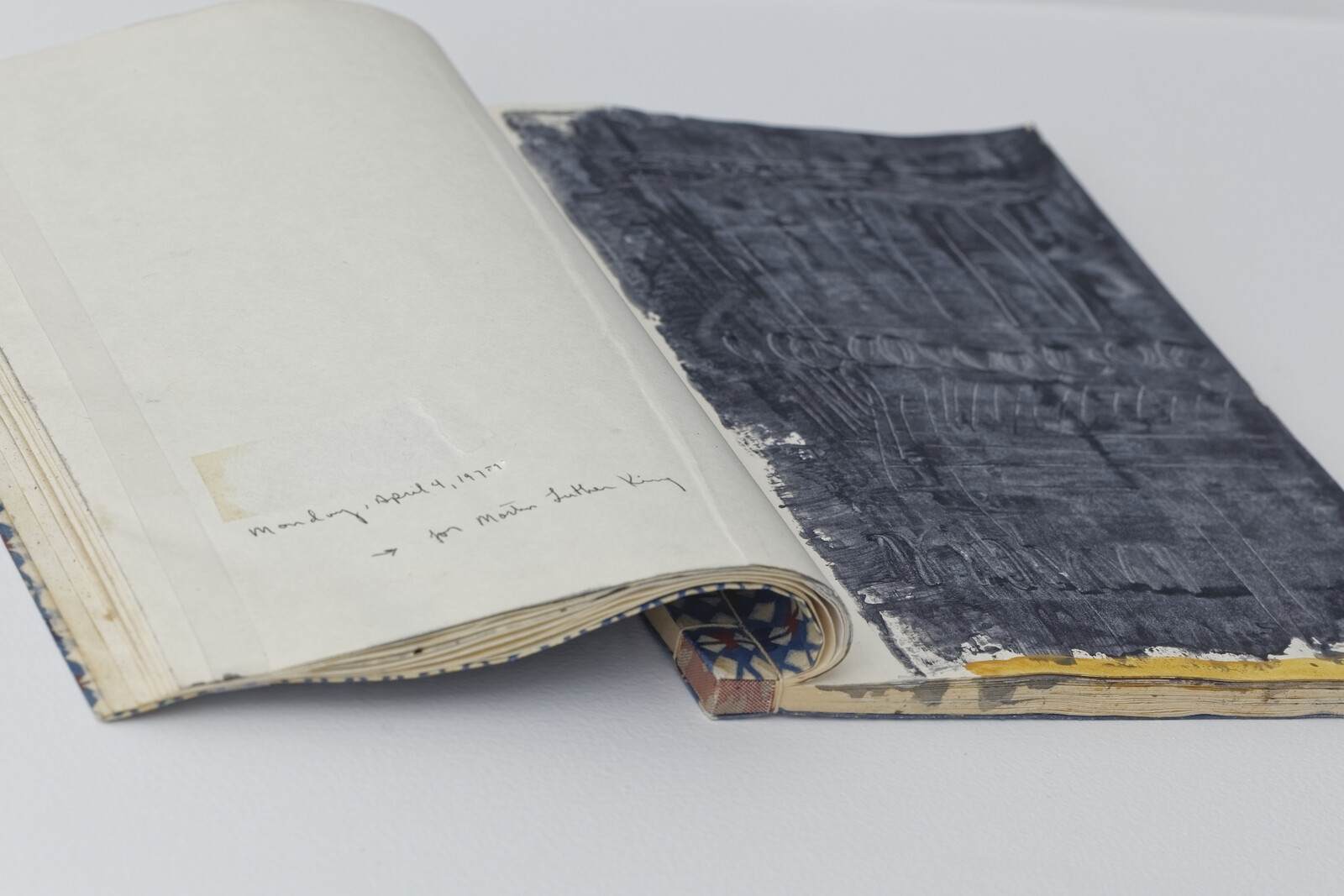

Shirazi draws on “Dialects of Isolation” as a historical foundation in order to demonstrate continuity between two generations of artists. Both exhibitions imbue racialized and marginalized narratives with fleshy, soft form rather than spectacularizing such difference in rigid ideological representations. Beverly Buchanan’s City Walls sketchbook (1976–77) is open to a page showing a wash of black ink smeared over marks that rise like welts through its messy field of color. On the other page the artist has scrawled, “monday, april 4, 1977, for Martin Luther King.” Buchanan’s book is displayed across from Andy Robert’s large ink, watercolor, and oil painting After Prince (2019), which is a mass of small colored dabs and lines on a large surface. The works insist equally on “enfleshed” abstraction, to borrow a term from Christina Sharpe. Shirazi makes no attempt to suggest influence between the juxtaposed works—this is not an exercise in canon-building. She is interested in how the body persists as an aesthetic ground for the experience of survival.

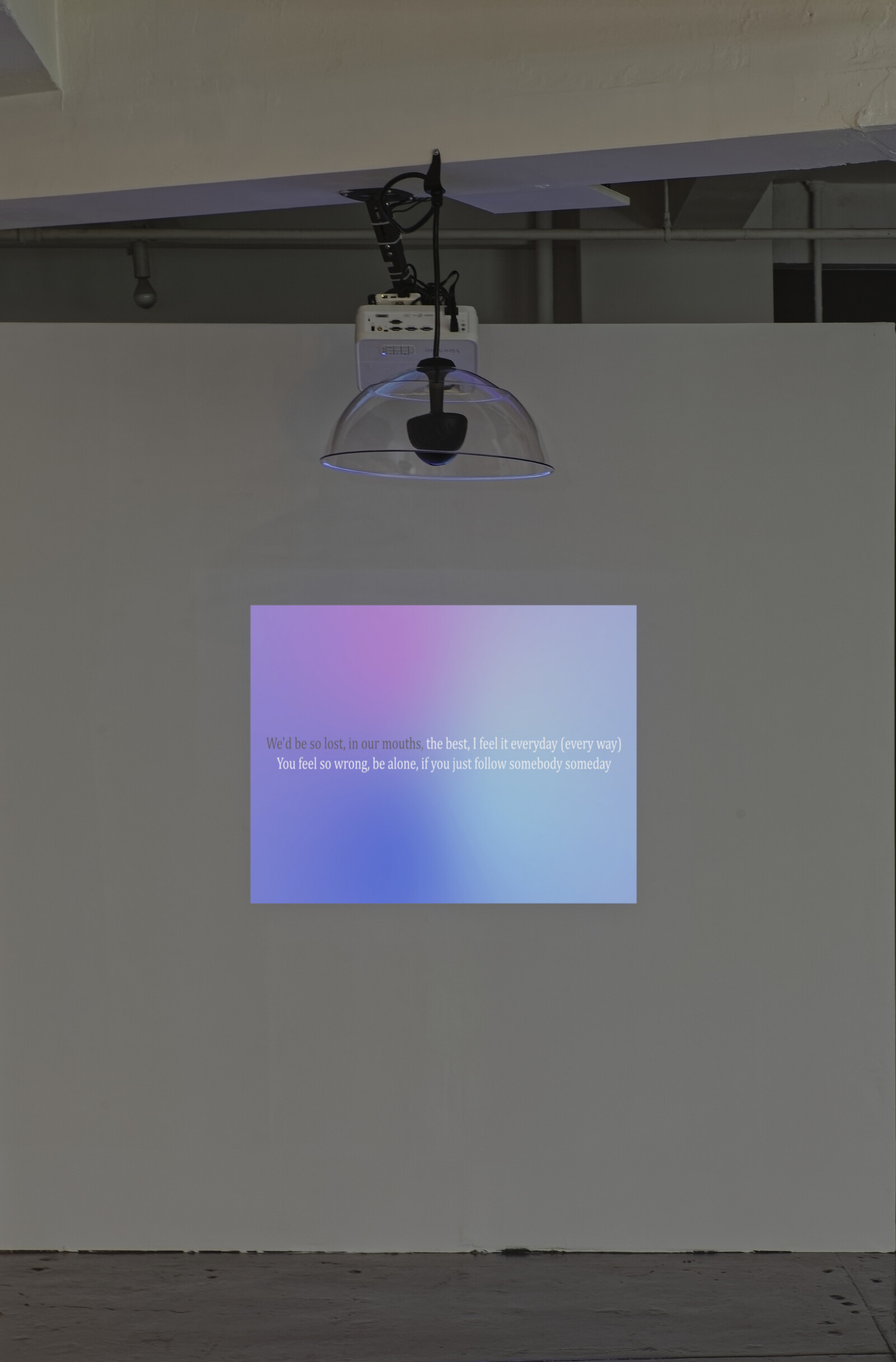

Arooj Aftab’s sound and video installation, also entitled Soft and Wet (2019), was created by stripping some of the sound from Prince’s eponymous song from 1978 and layering it with signal processing in other parts of the track. Like Mendieta’s breathing body, the resulting sound oscillates between the sensuous vulnerability of Prince’s voice and its immersion into the added layers of sound. Prince’s intensely charged lyrics demonstrate the imbrication of aggression and desire that runs throughout the exhibition: “Hey, lover, I got a sugarcane / That I want to lose in you / Baby can you stand the pain / Hey, lover, sugar don’t you see?” Aftab’s installation is a meta-text for the artists’ refusal (in either generation) to consent to singularity, not even in the “strategically essentialist” sense, to quote Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak on the necessarily contradictory response of subaltern feminists. Though Soft and Wet is sheltered by a sound shower, it bleeds into the adjacent and otherwise silent Burial Pyramid.

Corners (1980) and I Whispered to the Earth (1979), two works by Zarina installed on the far wall of the gallery’s second room, are different grids of regularly spaced indentations made with cast paper that glitter, producing an effect similar to that of mica in rock. They are juxtaposed with a sound work of guttural vibration issuing from a hole cut into the wall at the level of the groin, glory (2019), by Constantina Zavitsanos. If Zarina’s work poses the question, how far does one have to penetrate the surface of the world to locate its order? Then Zavitsanos’s work suggests that desire lies beneath that surface, inchoate and visceral; the search for order is in vain.

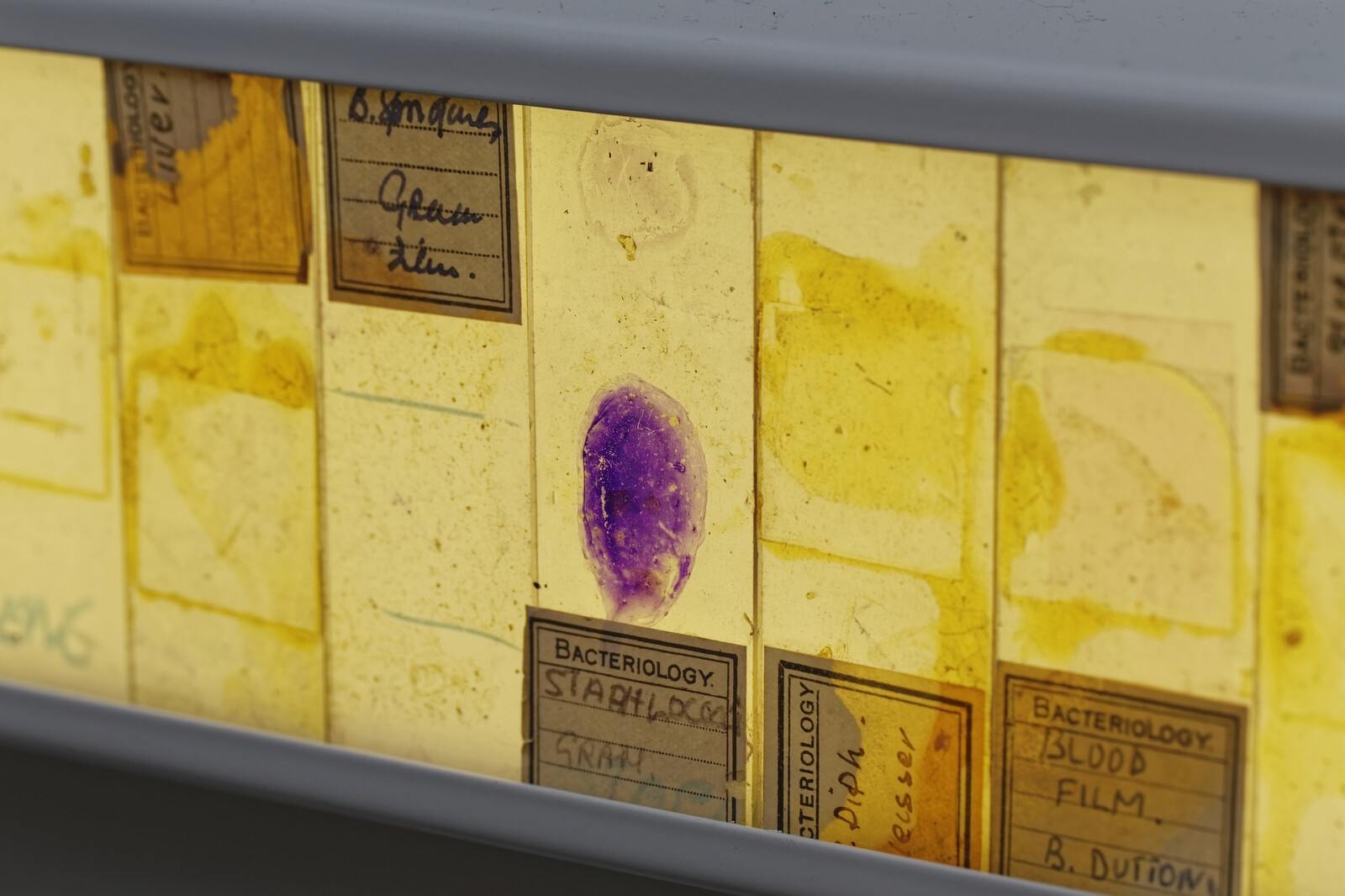

Though the call and response between Zarina and Zavitsanos is formally irresistible, the works by Crystal Z Campbell are more conceptually precise as a counterweight to Zarina’s pieces because they mirror the X/Y axis of Cartesian space while pointing to its violence. HeLa Project: Friends of Friends (Six Degrees of Separation) (2013) is a lightbox made of vintage bacteria slides from the 1940s. Degrading smears of medical dye on old glass give the sensation of painting seeping out of its framing logic along a strict horizontal axis. Portrait of a Woman I and III (2013) are two vertical plinths into which 3D laser cut solid glass cubes are lodged. The cubes were custom printed with an image of HeLa cells at the center of each. HeLa cells are the cell lines taken from an African-American cancer patient named Henrietta Lacks in 1951, which are the only cells to have survived continuously in the lab and are still used in medical research today. The two portrait sculptures are traces of the black body immobilized in transparent geometry, symbolizing the science built on the body’s ability to survive against all forms of structural violence.