A modernist critical framework would have you believe that the difference between a machine and sculpture is the same as between politics and aesthetics: a machine uses power to fulfill a function, while a sculpture is all about form and taste. Knowing that this is bullshit—that there is no apolitical aesthetic—our contemporary lives are defined by the somewhat analogous understanding that the difference between war and terrorism is the same as between art and non-art: purely a question of legitimacy.

Started in 1978 in San Francisco by Mark Pauline, Survival Research Laboratories is a collective of technicians who build freakish militaristic machines. They’re then employed in spectacular public productions that are part hilarious war zone, part robot drama, consisting of modified jet engines that shoot hurricanes of fire; remote-controlled six-legged crawlers that skitter and stab; and spark shooters and shockwave canons and wheelocopters that provoke a sort of childish, anarchic delight. However, there’s a political rigor to these radical machines.

Revered in the social circles of punk, noise, outsider junk art and other so-called “extreme” American subcultures, SRL’s VHS tapes documented these chaotic public events, which often ended in pissed off cops and fire departments even though proper permits were (usually) always acquired. It’s important to note, too, that very few injuries (and none major) to the public have occurred. (Pauline, however, badly maimed his hand while working on a machine, and had toes attached in place of the fingers lost.) Politically, Pauline was inspired by the radical far-leftists of the 1970s, including Bill Ayers and the Weather Underground—but rather than blowing up banks, he decided to create machines that repurposed the tools of war for reifying mechanical theater.

The show at Marlborough started with one such performance on the street outside. I missed it by a couple hours, since I myself was stuck in a flying machine, but from all the social media documentation it seemed tame, especially compared to other SRL events. Unlike “Crime Wave,” the 1995 show in San Francisco that set off a number of condominium alarms and helped get SRL permanently banned from doing performances in the city, the Marlborough opening appeared more like a light demo of the machines’ capacities.

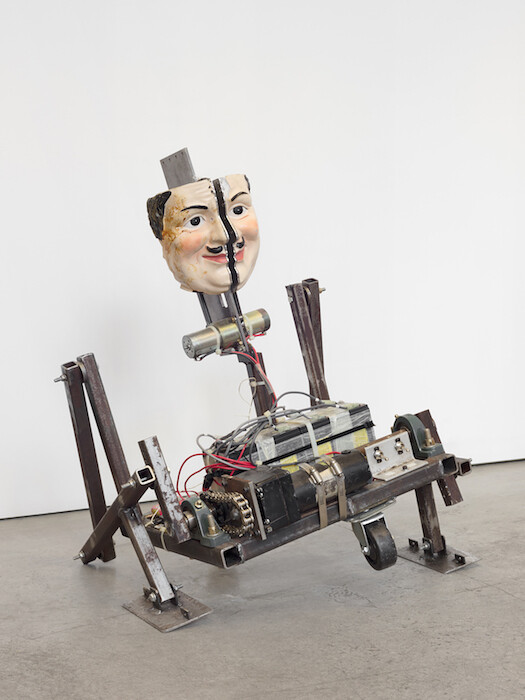

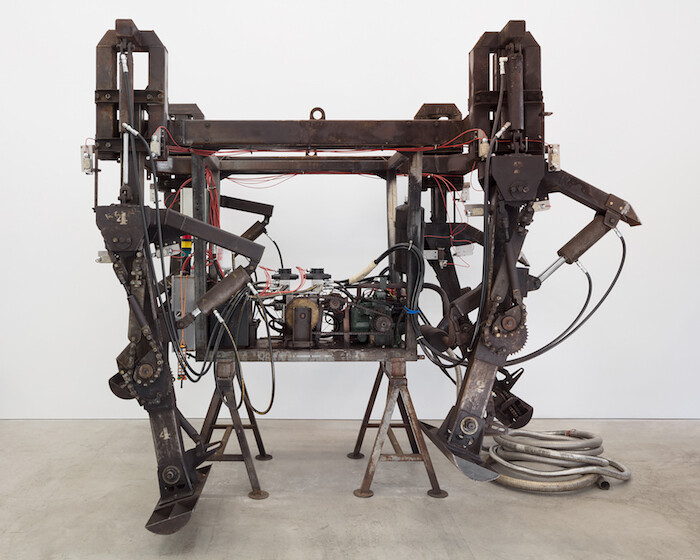

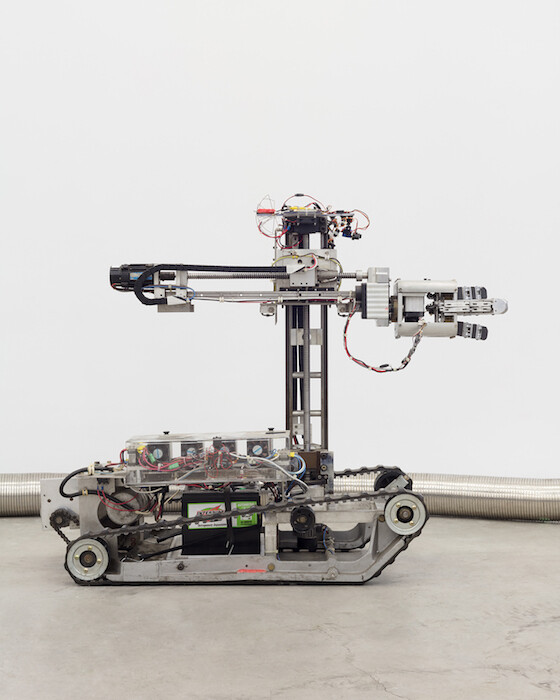

When I visited the gallery, it was odd seeing these works sitting silently in the white cube. These are kinetic objects, monstrous automatons, controlled mostly by humans but prone to their own violent volition. So seeing these gigantic machines, such as Spine Robot (2012-2014), with its long, tentacled claw hanging limply, or Running Machine’s (1992) six-legged steel carapace standing totally still, or the stationary weaponized wheel of the Pitching Machine (1999-2017), which, when activated, launches two-by-fours at high velocity into a tank, struck me as somewhat of a bummer. As is customary in the art world, these living works have been turned into objects. They’re beautiful objects, no doubt—the greased gears and pistons, frames rusty in some places, gauges and wires and fan belts are a pleasure to look at—but seeing them just sitting there, they feel like artifacts of a bygone apocalypse, a junk typology for the dustbin. But it is something beyond these machines’ objectification—their mummified state, as I experienced them—that engenders this feeling.

This is SRL’s first show in a commercial gallery space. In the front area of the gallery, posters from previous performances hang on the wall, where bleak images, tinged with a dark humor or apocalyptic industrial aesthetic, abound: figures in the throes of insanity, military men getting handjobs, bear traps and prehistoric skeletons and countless devices of torture surrounding production titles such as A Bitter Message of Hopeless Grief and An Unfortunate Spectacle of Violent Self-Destruction, the latter of which cost a two-dollar admittance. These seem to indicate a politics not only of anti-war and anti-capitalism, but a Deleuzian conviviality for the freaks and outcasts of society.

The punk in me—not in terms of a musical taste, but as Mark Fisher described it, that “confluence outside legitimate(d) space”1—felt like the whole thing was a glaring hypocrisy. I fantasized and felt infuriated by the idea that the machines in the pristine main room might be ogled at and bought by New York finance bros who get a simple-minded hard-on, whose only context for such a subculture is BattleBots or Junkyard Wars. I found myself wanting these works to not only re-tool the materials of imperialist capitalism and industrial warlords, but to physically demolish the art-retail space in which they stood. I wanted to see Mr. Satan (2007)— a sculptural relief of a chiseled, rusty, nickel-steel face—blow fire onto the too-white walls of the Chelsea gallery. I wanted to see Pitching Machine launch two-by-fours at the bourgeois exploiter class and dictatorial fuckboys. I wanted to see some shit destroyed because the world is fucked and why not start all over anyway?

However, this of course is a reactionary, juvenile response. It would be reductive to assume that a strict binary exists, that SRL can either be totally subversive or total sellouts, or that freak elements don’t exist in the financial sphere or in the military-industrial complex. And in fact, SRL’s whole practice has always been parasitic, one in which they buy out failing tech companies and purloin equipment from military contractors and create something new from the broken, discarded bits of corporations and Western warmongers. So maybe the show is a wrench thrown in the gears of this material economy, or at least into the fabric of our current cultural moment, which, though rightfully obsessed with Silicon Valley-technologism and ensnared in post-Fordist concerns, could use SRL’s reminder of the grinding machinery that continues to rip up earth and body alike.

Walking out of the gallery, I saw a crane building a new building across the street. Seeing this machine, giant and fluid compared to all the others I’d just witnessed, was perhaps more enlightening as to the critical stance the show should cultivate. Yes, seeing the still, static work of Survival Research Labs in a blue chip gallery might be sad—but these theatrical machines, built by a transgressive, boundary-pushing team of weirdo engineers, never actually stood a chance in physically combating the machines of late capitalism. Indeed, that was never their purpose. So we’ll have to fabricate other means instead.

Mark Fisher, “Why K?,” k-punk (April 16, 2005). http://k-punk.abstractdynamics.org/archives/005358.html.