A citywide rally on December 8, 2019, marked six months of pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong. 800,000 people attended—a tenth of the total population. When I arrived the following weekend, the streets were quiet. I wasn’t there for the protests—I was there to see art. Yet I couldn’t escape the feeling that we were, as Allan Sekula wrote of the 1999 Seattle protests, “waiting for teargas”—in the lull, anticipating the moment when revolution and counter-revolution show their true selves. Meanwhile, the Hong Kong police were thinking about art, too. On December 12, they posted a parody of Maurizo Cattelan’s Comedian sculpture (2019) to social media; in their version, instead of a banana, a teargas canister is duct-taped to the wall. This is possibly the most pitch-perfect, frank response from the government so far: lobbing riot grenades is a day job for some, but only an artwork can express the underlying depths of official apathy. The Hong Kong “banana” joined the graffiti along the roadways in Central, slogans like “thx president trump / make hk great again” and “je me révolte, donc je suis”: messages meant, on some level, for outsiders like me.

The art scene, too, seemed to be steeling itself for whatever’s next. Or was I hallucinating the teargas? At Tai Kwun, a kunsthall in one corner of a bustling cultural complex built in and around a nineteenth-century police headquarters and jail, was an exhibition called “Phantom Plane, Cyberpunk in the Year of the Future”: paintings, videos, sculptures from the last 60 years that seemed to presage, again and again, the grim triumph of corporate capitalism. Neon Parallel 1996 (from 2015) by Jon Rafman tells the story of a chatbot’s search for her identity; the footage, in fact shot in Istanbul, recalls how images of Tokyo, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and other Asian megacities have long served to flavor western dystopias. The 1990s are represented by microscopes with human faces in Interview (1998), a painting by Tetsuya Ishida; the ’70s by Bettina Von Arnim’s chunky, geometric visions of spacesuited figures like the one in Flammenwerfer (1973), spraying rainbows from a flamethrower. The videos at a related screening by Metahaven (2013), Cecile B. Evans (2014), and Wanuri Kahiu (2009) felt dated—over before they began—since the worries these artists described, from water wars to the dissolution of the “self” in digital mists, have already come to pass. But this wasn’t quite it. A 2019 video in the exhibition, Student Bodies, by Ho Rui An, traced the fate of Asian student movements under colonialism, from the post-war Japanese diaspora to the 1976 Thammasat University massacre in Bangkok. A memorial at the latter site features the bronze faces and limbs of martyred students merging with an undulating granite plaza. Yet Ho’s work felt especially timely; it will surely feel timely again.

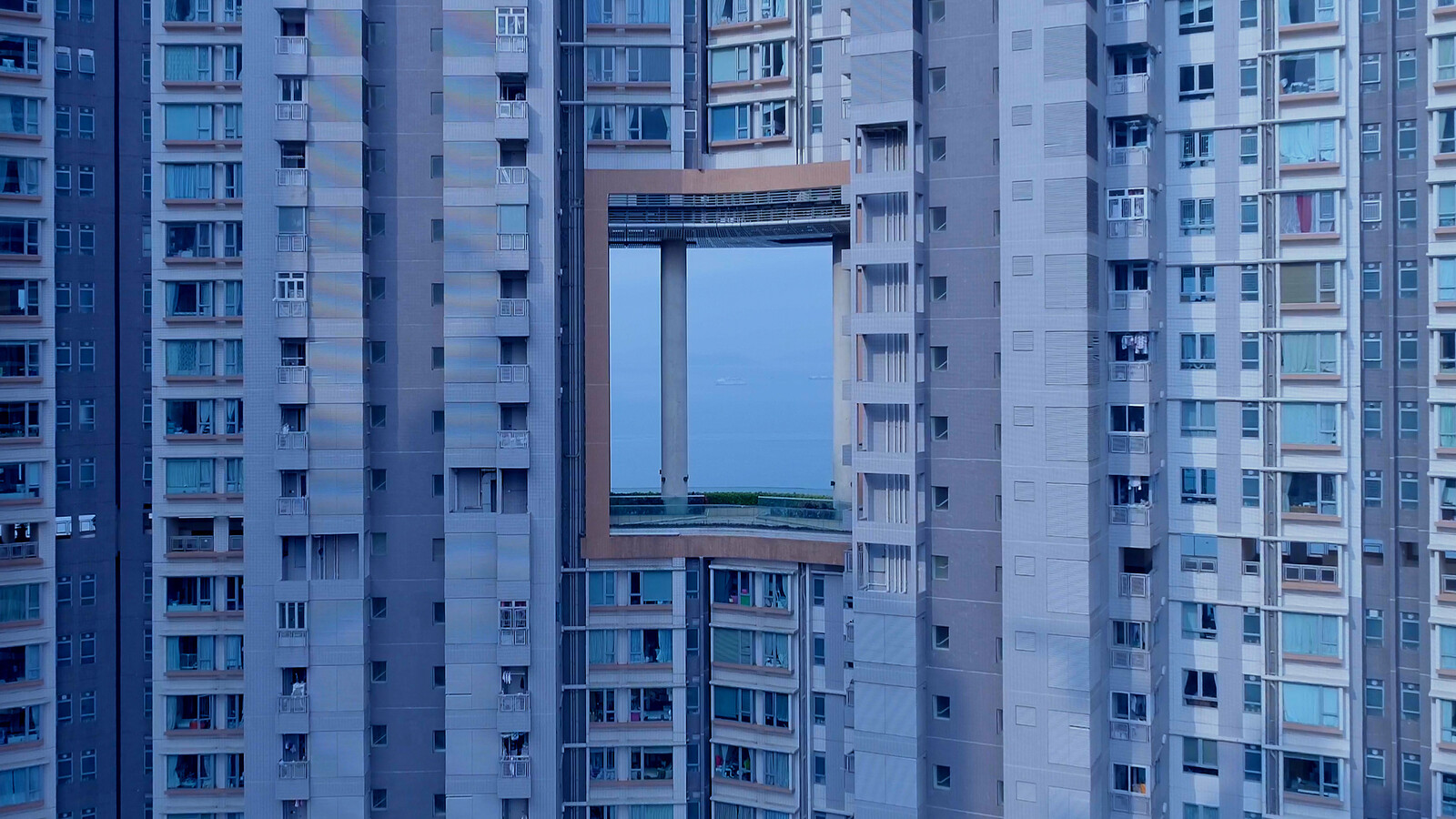

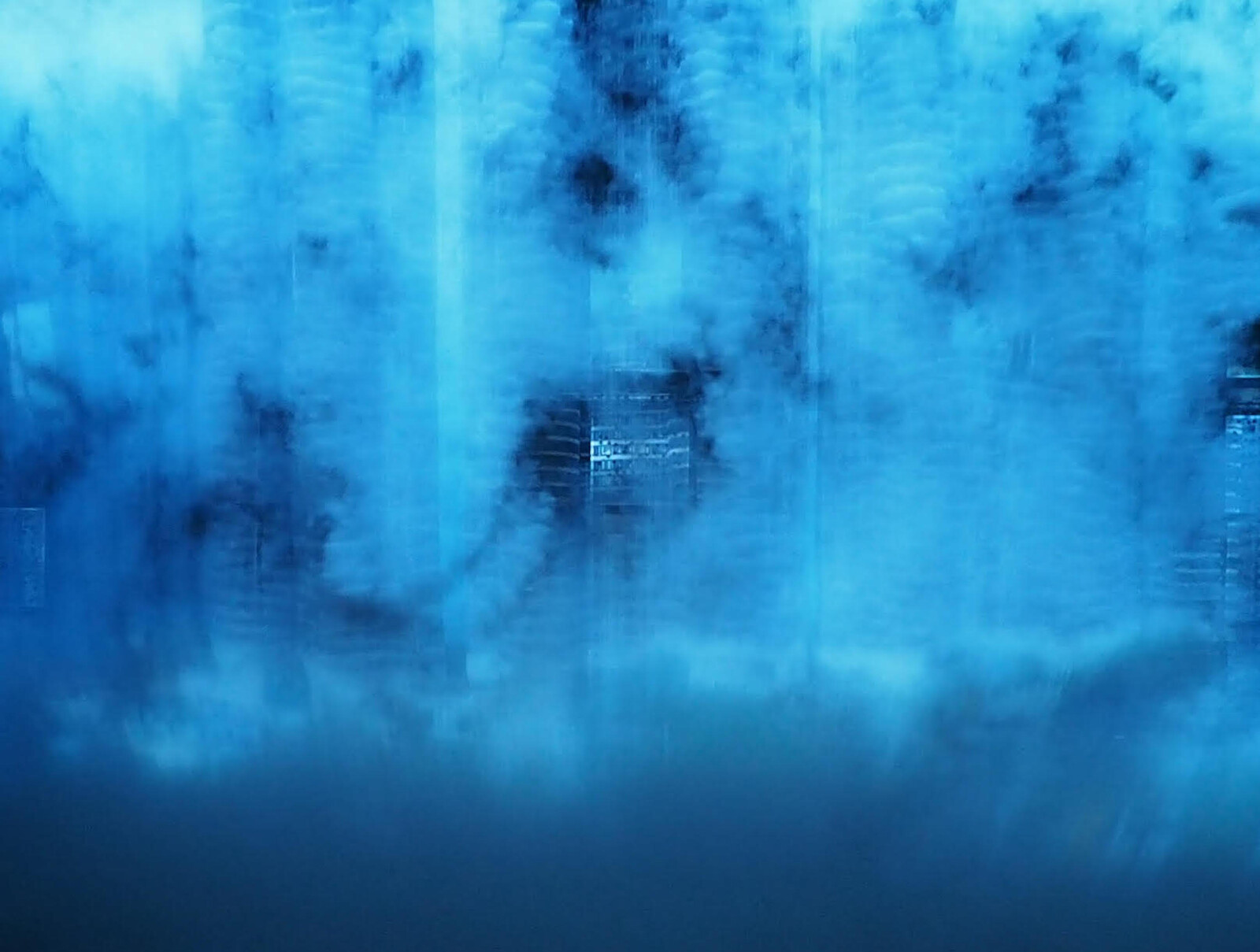

Waiting for teargas—a state of anticipation, anxiety, and familiarity; police violence, popular unity; the prospect of incremental change, or of crisis as usual. In many ways, resistance is already a way of life. A video at Blindspot Gallery by WangShui, called From Its Mouth Came a River of High-End Residential Appliances (2018), features an exclusive high-rise apartment complex on the island’s west shore, a set of five towers in beige and lilac blues that incorporate huge square openings, several floors high, in their middles. The drone-mounted camera executes three slow pushes through these holes as the artist narrates both the story of the buildings and their own negotiation of identity politics—not to say identity itself. Flying the drone so close to these buildings, let alone through them, is illegal, but the buildings themselves are defiant, too: the holes, found in towers throughout Hong Kong, are meant to allow dragons free passage, and express principles of feng shui that, along with other spiritual practices, have been outlawed on the mainland since 1949.

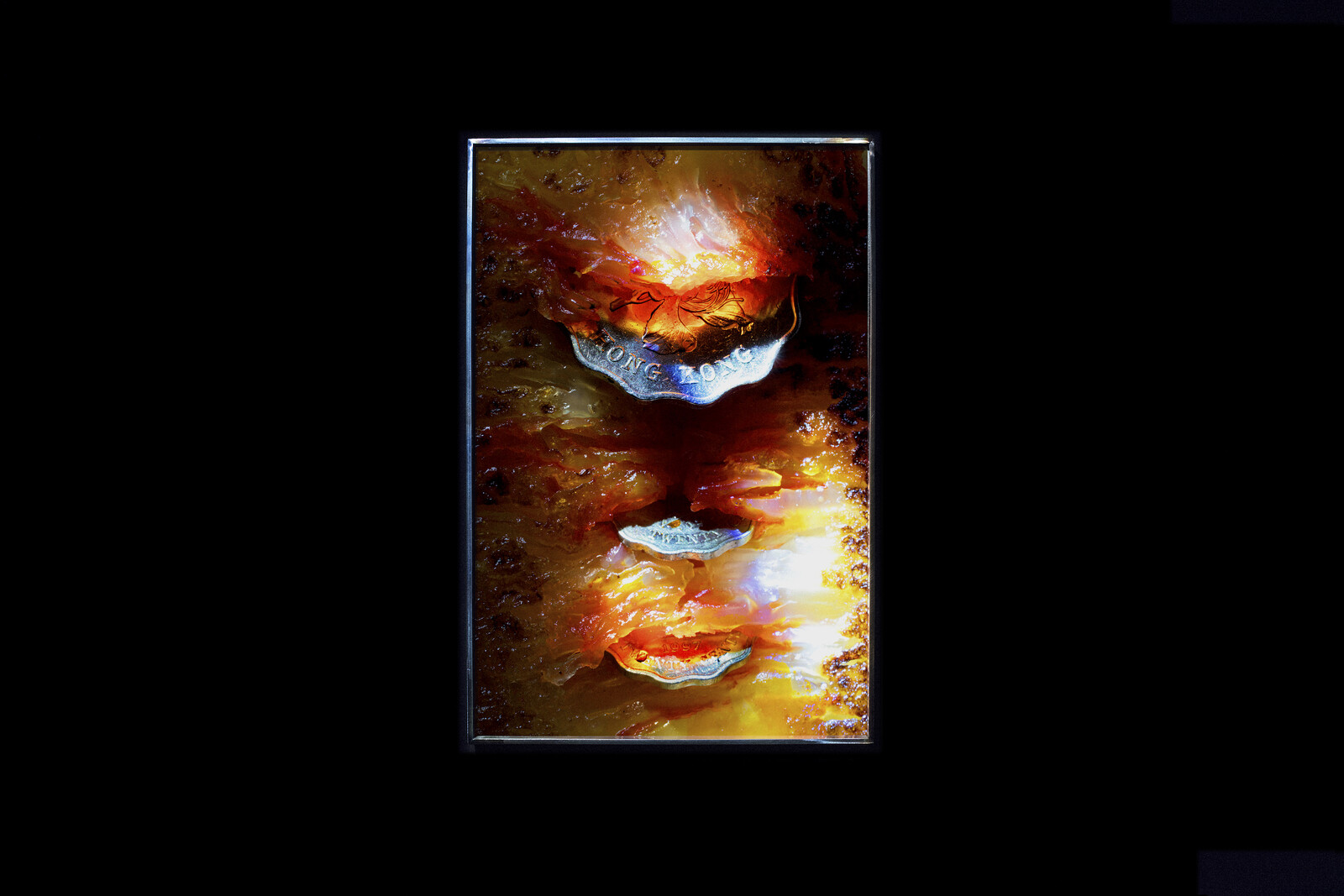

Speaking of holes. Diane Severin Nguyen spent the last three months in Hong Kong preparing a show at Empty Gallery. The space is a box painted black from floor to ceiling, lit only by the spotlights on Nguyen’s photographs. Her still lifes push amalgamations of consumer products, both grown and made, into a dayglow limbo between figuration and abstraction. You might recognize the fine diamond texture and sluglike, ribboned forms of Polymer Luck (all works 2019) as a utility glove of the sort surprisingly common on Hong Kong’s streets. The photo is backlit, smoky, almost silver. Another photo, titled In Her Time, depicts what could be a fruit, with Hong Kong two-dollar coins stuck in its side like the tiered balconies of a 40-story estate. Nguyen partitioned the gallery using the sort of loosely woven nets that wrap construction sites across the city. The photographs, framed in thick steel, seem burned into the space, yet the overall feeling is one of transition—consumption and re-consumption, image-commodities made from the quick markets of Cyberport and Kowloon. The exhibition is titled “Reoccurring Afterlife”; it is exactly that, a cycle of possession and desire so fast that it seems to stand still.

As they circle the ring roads, Hong Kong taxis advertise the city’s opportunities for art collectors. They mean the vertical mall at 80 Queens Road in Central that is home to franchises of David Zwirner (5-6/F), Pace (12/F), and Hauser and Wirth (16–15/F), among other galleries—as well as a sportswear outlet and a skincare spa. On view at Zwirner was a new body of work by Carol Bove; glossy circular prisms gave an anthropomorphic touch to collapsed, matte-colored forms made from crushed steel. It looked like a bunch of napping John Chamberlains. Zwirner and its neighbors felt less like marketplaces of ideas than showrooms for lux design. Admittedly, it was a very nice mall. On the building’s roof, a Yayoi Kusama spotted pumpkin sculpture adorns the bar, a selfie spot open to the sky behind two sets of stanchions. Across a sea of air was a skyscraper covered in bamboo scaffolds, all sheathed in green netting. The skyline blinked and spazzed with secular Christmas decorations, sheets of LEDs draped on the tallest towers beaming big ornaments and teddy bears and wrapped gifts. There is the freedom on the streets below, and there is the freedom up here; what unites them is an unbending faith in choice. Consumer choice, you could call it—or the choice to consume. In this way, Hong Kong in December 2019 was a history lesson: how to wait for teargas when the teargas is already here.