Dear Chris,

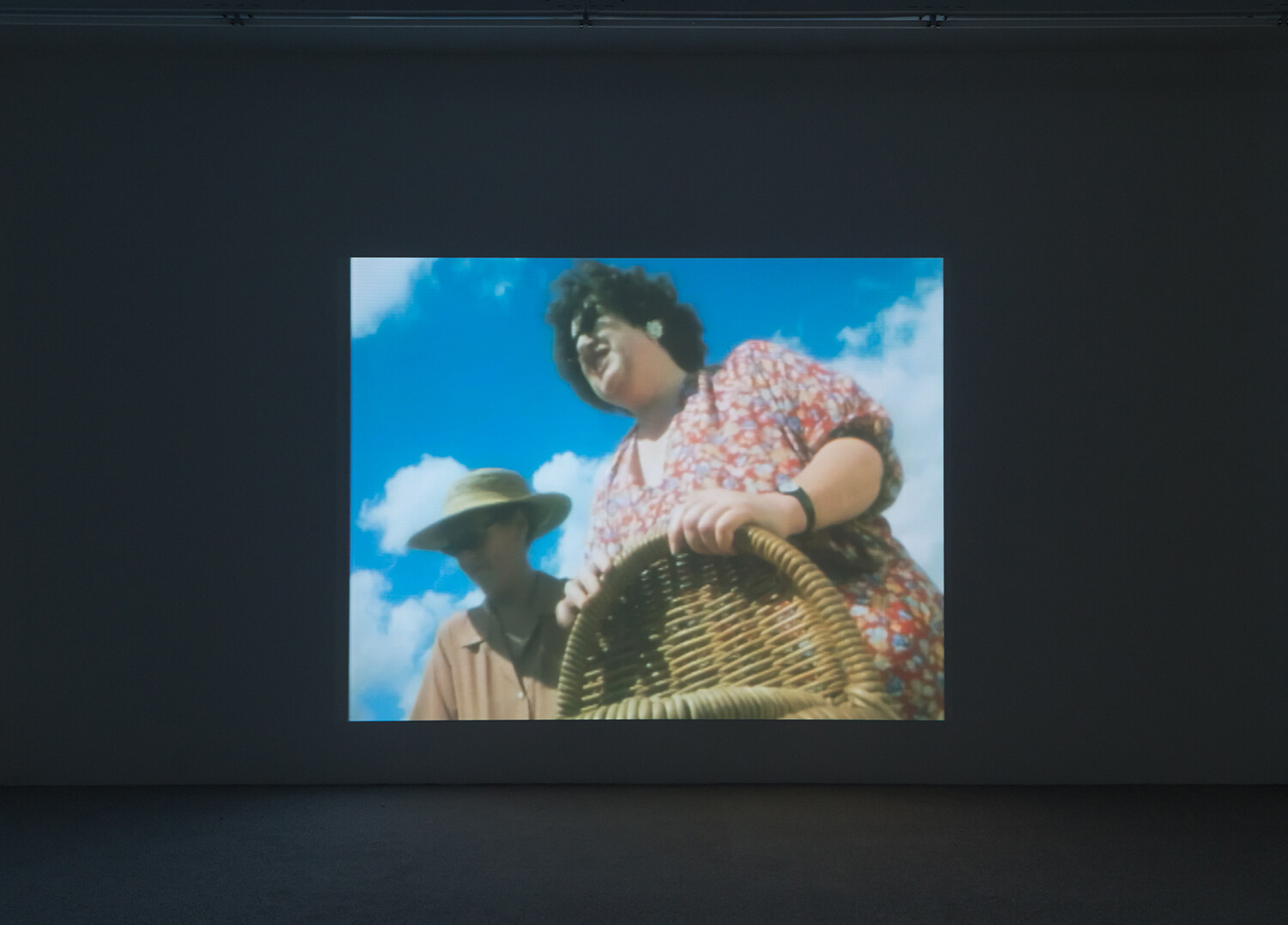

How sweet it was talking with you at the opening of your show. You allowed me to introduce myself, so I could share some words I have longed to tell you since I arrived in this city. I was introduced to Los Angeles through your writings: a primal, unfettered education in the local art scene; I know it well enough now that my interest has begun to wane. I feel like Gravity—the main character in your film Gravity & Grace (1995), one of nine on view at Château Shatto—when a stranger rests his head between her legs and she stares into the void, seeking something meaningful, relevant, eternal. The way you edited that scene—the way you edited your entire filmography—reflects the way you write. You speak the way your characters speak.

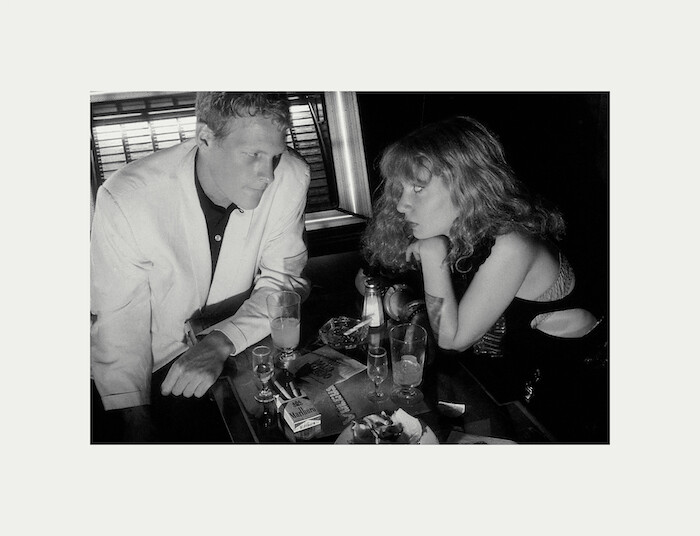

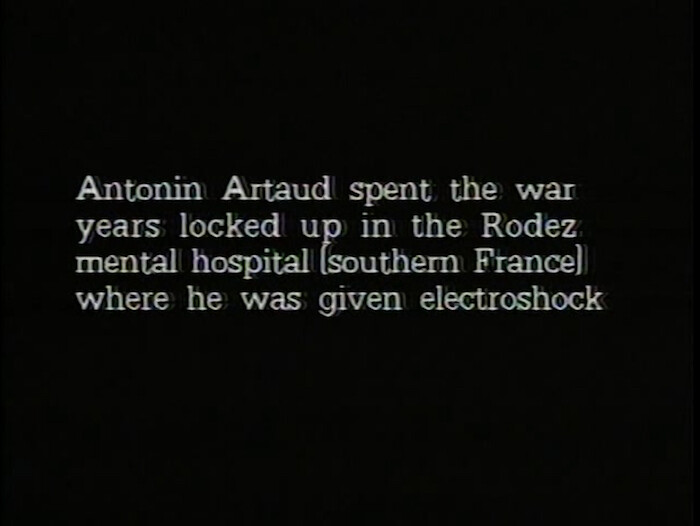

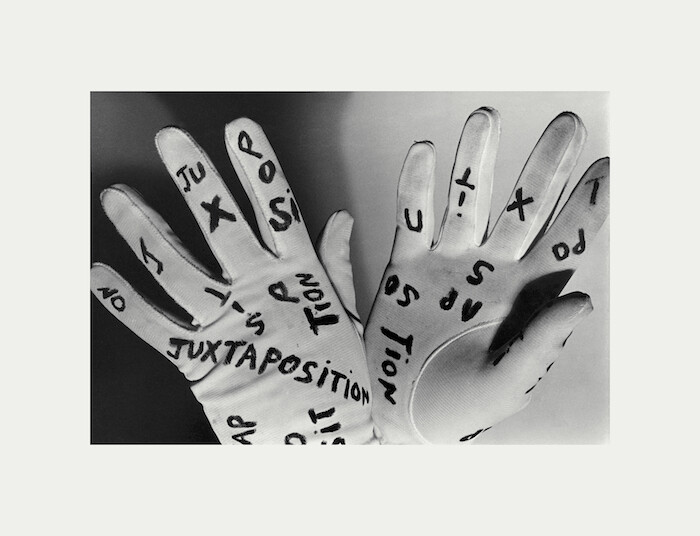

I hear your voice throughout these films. Formally, they range from documentary—such as Voyage to Rodez (1986), in which you recount an episode in Antonin Artaud’s life, and Traveling at Night (1990), about a field trip to a deconsecrated Wesleyan Methodist Church in Darrowsville, New York—to fiction. Sadness at Leaving (1992), for example, is based on Erje Ayden’s 1987 autobiographical novel of the same name, about his time as a Turkish spy. But it’s the Super 8 film In Order to Pass (1982) that helps me understand your motivation. In one of the intertitles, which interrupts footage of a group of artists in the woods, you write: “The fantasizer locates the ideal state but then uses the imagination to create a progression into the present and future.” You suspend everything in a constant state of transition. The harrowing consequence is that what comes next is neither gentle nor satisfying. Reality, in your work, is an endless battleground.

I’ve spent a long time sitting on the park benches in the gallery, staring at the old monitors on which your works are shown, paying close attention like an obedient schoolboy. I have witnessed, in your films, a pathetic parade of wounded humans negotiating their destiny without complaint. When Gravity explains to her bored students that it’s essential to identify the subject and the predicate of a sentence “so that everything else falls around and you don’t get lost,” I hear the core of your approach to writing. When your camera wanders through an urban or rural landscape, I think of the way you juxtapose narratives, from domestic details to political realities. By merging Bach’s Partitas, or Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto in A Minor with 1980s dance music like Laid Back’s “White Horse,” your soundtrack is the soundtrack of invisible extras trying to live their lives as protagonists of a painful pantomime, a chain of events without climax. In Terrorists in Love (1983) a young woman reads a manifesto to a small crowd in a bar. Everyone has a plan but nothing works out, and they all find each other in a middle of a field in an imaginary boat, swaying. When, in How to Shoot A Crime (1987), you combine footage of a crime scene with BDSM imagery, you render the latter pop before edgeplay went mainstream. “You have to feel,” the Mistress says. Is it possible to be more vulnerable?

I watched Gravity & Grace so many times that I have memorized the dialogue. During the opening scene of the film, I am elated to start a new journey in your company. But as the end credits roll, I realize that nothing consequential has happened. So I watch it again from the beginning, hoping for a different ending. Everything in your work is always on the verge of change: that imperceptible gap between reality and a better reality is so excruciating.

I don’t understand why you refer to these films as failed attempts: “I tried my best but it still failed.”(1) I disagree. Your films merge a sense of elevation, in the Baudelairean way, with the urgency of avoiding the disgrace that haunts all of us.

This is something I would have loved to discuss with you, but our time was limited. We talked about Louise Bourgeois’s series of drawings “Red Skies” (2007–09), about Jill Soloway’s recent TV adaptation of I Love Dick (1997)—then our conversation vanished. You were surrounded by friends and close colleagues. The opening was important, if you care about such things: a gathering of people who wished to celebrate your impact on their lives. I talked with Liv, the gallery’s owner and founder, who admitted that one reason she moved to Los Angeles was to increase the likelihood of your attendance at her exhibitions. I guess she achieved her goal.

In that moment, I had to disappear discreetly: I have always enjoyed avoiding goodbyes and formal closures. A bit like Dick in I Love Dick, when he sent you a photocopy of his letter to Sylvère Lotringer as a final goodbye. How harrowing was that ending?

I would have loved to tell you that no one better understands how Gravity feels when, disappointed by the false promises of the cult she is following, she decides to leave New Zealand. I spent many years in an ashram and have walked the fine line between faith and—to quote from the film—“bullshit.” The way she abruptly moves to New York reflects how I arrived in Los Angeles. And when I arrived, you were present. Your work became my secular scripture.

That Saturday, Chris, I’ll never forget. As you looked into my eyes, perhaps you saw the rare delight I’d found in your words and films. When I left, I felt a need to be closer to you. And now, having written this letter, which I hope you will have a chance to read, I feel better.

P.

(1) I Love Dick (New York: Semiotext(e), 1998, 2006), 80.