The centerpiece of Deimantas Narkevičius’s current exhibition at Maureen Paley is a holographic screen—a small block of glass on a sleek metal shelf. A nightingale appears in the glass and lands on a branch that hangs there, while audio plays of a flute mimicking birdsong in sync with the movements of its beak. It flies out of view again and then returns, left and right, left and right. On an adjacent wall is another branch of sorts—a bark-like bronze cast of the cavities inside a flute—and nearby hang two small black-and-white images: a 1920s photograph from the Lithuanian State Archive of a soldier playing the flute by a window and a digital recreation of the same scene from directly outside the building. This perplexing constellation of objects is named after the shadowy figure in the photograph, The Fifer (2019).

Holography represents the height of illusionism, elaborately conjuring animated three-dimensional images. But the nightingale’s restless movement in and out of frame continually calls attention to the screen’s edges, where the projection falters and the empty glass block becomes visible. The illusion is further ruptured by the flutist’s birdsong which, isolated from any ambient sound, is unconvincing. Each item here performs a failed attempt to find depth, confronting us with only surface. Narkevičius materializes the interior of a flute by creating a solid mass with only exterior. He claims the cast captures the instrument’s “essence,” but it resembles another object altogether—a branch. And he responds to an obscure old photograph by reproducing the scene from the outside. Instead of offering a revelatory view into the building, the resulting picture shows just window reflections and brick wall. It shuts us out, confirming our distance from the original photo. Narkevičius’s work renders the search for depth or truth futile: subjects (the nightingale, the flute, the fifer, the past) metamorphose and disappear in his hands.

The artist’s early, nine-minute film Europa 54° 54′ – 25° 19′ (1997) plays on an old TV in the gallery’s larger room. It documents a drive he took “one Friday morning” from his flat in Vilnius to the (much-disputed) geographical center of Europe less than twenty miles away. Trams, buses, and cars roll along; pedestrians wait at crossings and walk past; ornate nineteenth-century facades in the town are replaced by suburban apartment blocks, illuminated by strong sunlight against a clear blue sky. In a monotone voiceover, Narkevičius explains that he has travelled equal amounts east and west of this point, so for him it is the center of time “spent elsewhere.” A smashed-up car lies on the hard shoulder; roadworkers excavate the pavement; two men pass with a donkey. He turns off the main road and eventually completes his voyage on foot, walking across a stream and up a small hill to the stone that marks the spot.

Narkevičius personifies here the new internationalism of post-Soviet Lithuania, driving towards a monument that marks not history or culture but a position in relation to “elsewhere”—that is, as he acknowledges, an expression of “ethnocentric ideology typical of a young country.” The film is enlivened, though, by tension between his journey and the reality he records on the way. The camera moves ceaselessly onwards to reach the center while people and vehicles slip by—forwards and backwards, left and right—their scattered movements antithetical to the artist’s linear progress. His musings on the relationship between distant travels and his hometown sound pretentious—perhaps knowingly—alongside the sight of pedestrians going about their days, oblivious to his grand mission. And, most obviously, his trip to the “center” takes him away from city and people to an empty field. With these juxtapositions the work elegantly allegorizes the uneasy encounter between cartographic abstraction and the fabric of society, geopolitics and life.

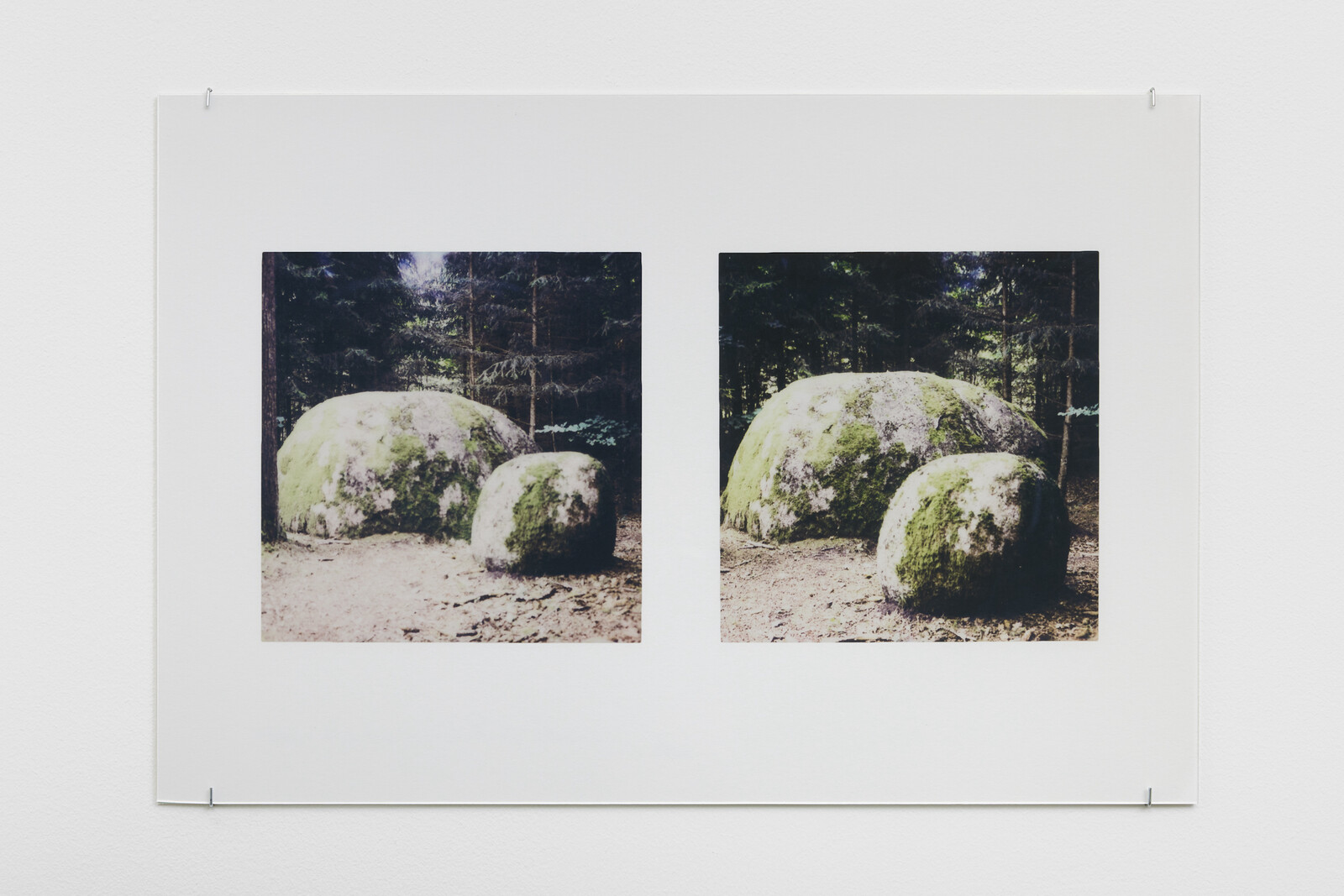

On the wall to the right is “Akmenys Po Du” (2023): a grid of sixteen pairs of photographs—each of a different boulder, each incidentally recalling the rock that marks the middle of Europe. These vast stones, which mysteriously appear across Lithuania’s landscape, feature prominently in local folklore. Narkevičius’s exquisite enlarged Polaroid prints pay testament to the majesty of these sites: to the country’s beauty and heritage. The display of numerous stones as doubles in a grid, though, undermines their power as singular, miraculous objects. This simultaneous celebration and subversion is typical of the work on display here—which upholds contradictions between singularity and multiplicity, essence and resemblance. Narkevičius concludes his journey in Europa 54° 54′ – 25° 19′ with a flippant denial of its significance: he describes feeling that he “had been there before,” that it “could have been anywhere in Europe.” His work articulates post-Soviet ambivalence—delighting in the histories and mythologies of his country while remaining skeptical of the construction of origins and essences central to nationalist ideology.