The Garden of Six Seasons, which lends its name to this “precursor” to the forthcoming Kathmandu Triennale, was designed by the architect Kishore Narshingh in 1920 for Kaiser Sumsher Rana’s palatial home in the capital of Nepal. The group show, held across two sites in Hong Kong, takes the entangled infrastructures and cultures that produced the garden—Edwardian neoclassical design transplanted to Nepal—for its organizing concept. In doing so, it establishes a space in which varied vantage points on the world can be expressed and different cosmological systems explored; by packing 150 works together in narrow spaces and under low ceilings, the curation forces the visitor to read diverse works together, and to make unexpected associations between them. Individually and collectively, they relate to local mechanisms of imperialism, feudalism, and modernism, but also indigeneity as a means of resistance, resilience, and remedy.

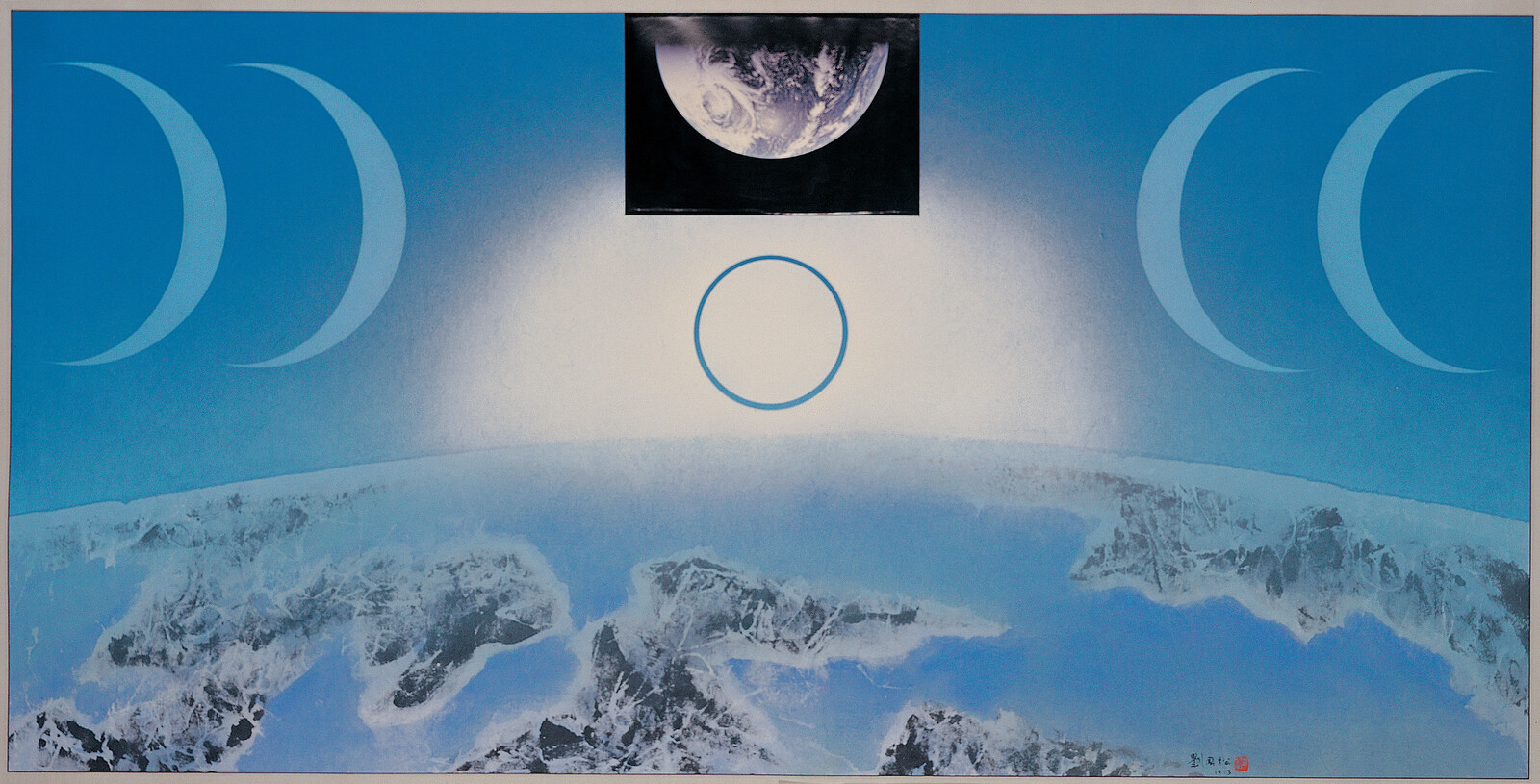

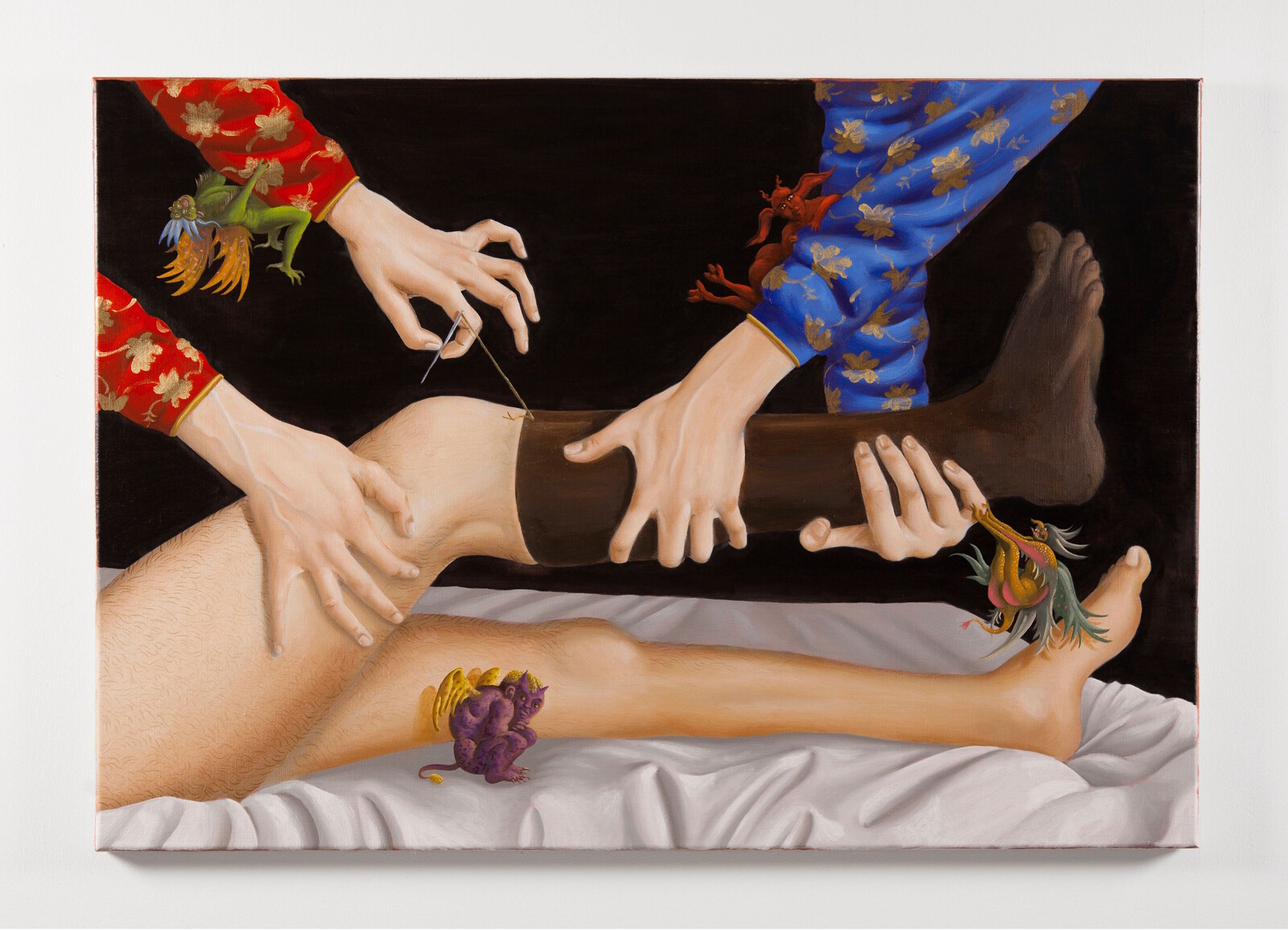

Para Site’s exhibition space in North Point speaks to how the eclectic design of the Garden of Six Seasons—in which Chinese elements coexist with Roman columns—undoes the positivist and empiricist connotations of neoclassical architecture. You enter via an outer corridor in which, according to the accompanying text, “artworks connect our bodies, their insides, the networked maps of our social worlds, and the cosmos.” Liu Kuo-Sung’s scroll work The Ring B (1973) hangs across from a nineteenth-century representation of the cosmos, and both articulate the exhibition’s interest in presenting different ways of ordering knowledge. The core of the space, with a squarish plan and orthogonal axes, resembles the Persian more than the neoclassical garden, and reflects on “what is to be healed, what can be left untouched, and when to let go.” Placed opposite one another, Batsa Gopal Vaidya’s oil-on-paper Ayurvedic Yantra II (1971) depicts the symbols used in traditional Gazipur medicine, while Patrizio di Massimo’s oil-on-canvas The Ethiopian Leg (2020) retells the Christian story of the twin saints Cosmas and Damian, who were reputed to have transplanted the leg of a dead Ethiopian onto a white man’s body.

The garden is defined by its separation from the outside, and the exhibition at Soho House moves beyond the garden’s walls: here, a more documentary and less abstract mode is in evidence, although this analysis is also complicated by subjectivity and self-reflection. Take for example Liu Chuang’s three-channel video installation Bitcoin Mining and Field Recordings of Ethnic Minorities (2018), which researches industrial projects in southwest China. In doing so it draws attention to how the modernities of Europe and Asia collapse into one another, creating new and composite realities. Hao Liang’s silk scroll Fire and Water (2013–14), in which animals take refuge in the diminishing space between a raging fire and a rising sea, reflects on our relationship with a changing environment. The Uzbek ikat tapestries and Moroccan Azemmour embroideries that hang on the walls of Soho House, meanwhile, conjure the original garden: early Persian gardens, or pari-daizi, provided the inspiration for the first walled gardens in Spain and the etymological root of “paradise” (through the Greek paradeisos).

Indeed, both the original and the restaged Garden of Six Seasons are hybrids and translations. The original garden’s pavilions represented the six seasons of the region’s climate, while the moon gate, the stone urns, and plants from around the world were intended to summon Eden. Trevor Yeung’s two sculptural works, Volcanic lover 3 (2019), composed of volcanic rock and coral skeleton, and Our home is too small for you (2017), which juxtaposes Venetian lion-head terracotta pots with clay figurines reading books, are among the works that speak to this eclecticism and entanglement. Britta Marakatt-Labba’s Siellu (The Soul) (2003), which combines fish skin and embroidery on linen in its depiction of indigenous Sami life, is another.

Two standout works in the exhibition seem particularly to resonate with contemporary discussions around the environment and identity. Balinese artist Citra Sasmita’s ink-on-leather installation Timur Merah Project II; The Harbour of Restless Spirits (2019), which refracts creation myths through the lens of contemporary concerns about environmental destruction, and the celebrated music video director Andrew Thomas Huang’s single-channel installation Kiss of the Rabbit God (2019), in which a Chinese-American waiter falls in love with a Qing Dynasty deity, create spaces in which it is possible to imagine other futures by mediating the present through fantasy. They also illustrate how, by creating a space in which such different works can be housed, the curators allow each to flourish individually and in combination with their nearest neighbors. By proposing a methodology of knowledge production which is nonlinear, nondeterministic, and nonhierarchical, the curators of this exhibition practice good gardening.