In his 2014 lecture “The Future of Forensic Science in Criminal Trials,” judge Thomas of Cwmgiedd, Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, identified a communication problem. In light of the increasingly complex science used in court, he called for a set of judicial primers: standardized documents, written in “plain English,” to relay core scientific principles to lawyer, judge, and jury. Contrary to narratives propagated by popular crime dramas, he argued: “however eminent and reliable the expert, the presentation of forensic evidence is rarely black and white.”1

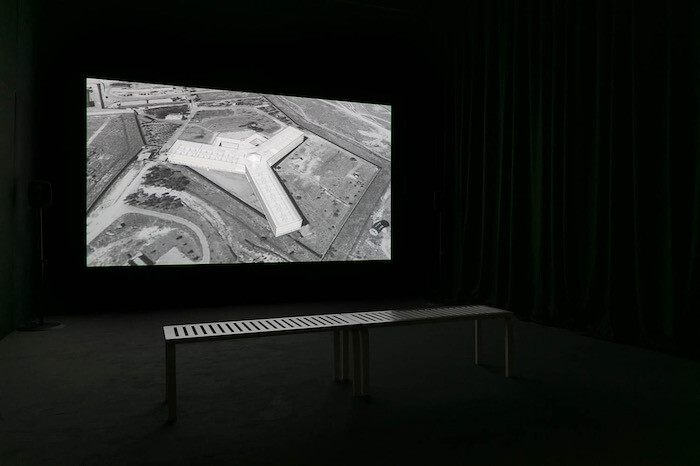

The slippery, kaleidoscopic status of evidence feels like the point and not the problem in “Counter Investigations,” a survey of work by Forensic Architecture, a research collective of academics, investigative journalists, and creative practitioners including architects, programmers, and filmmakers. Slickly installed across the Institute of Contemporary Art’s two floors, a series of multi-disciplinary investigations into human rights abuses and armed conflict unfold across video installations, models, and wall graphics. Described by Forensic Architecture founder Eyal Weizman as “the archaeology of the very recent past,”2 the group use forensic methods to map and reconstruct sites, such as the Saydnaya Prison in Syria, or events, such as Israeli military operations in Rafah, Gaza, in August 2014.

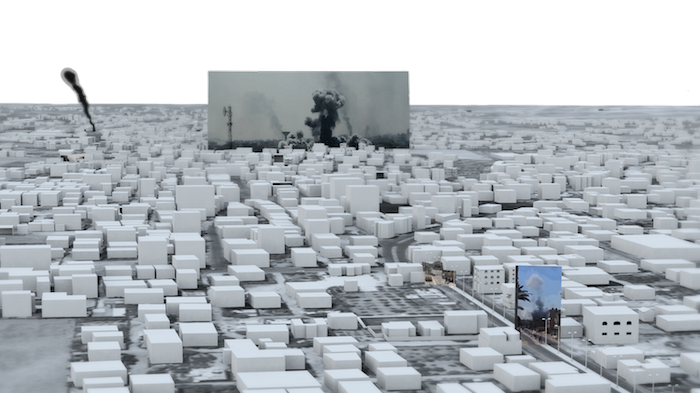

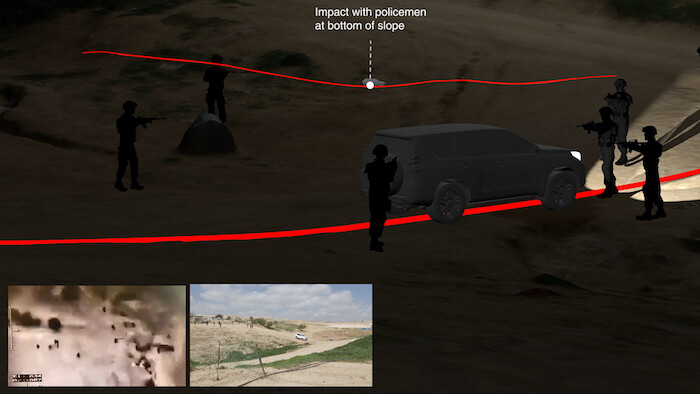

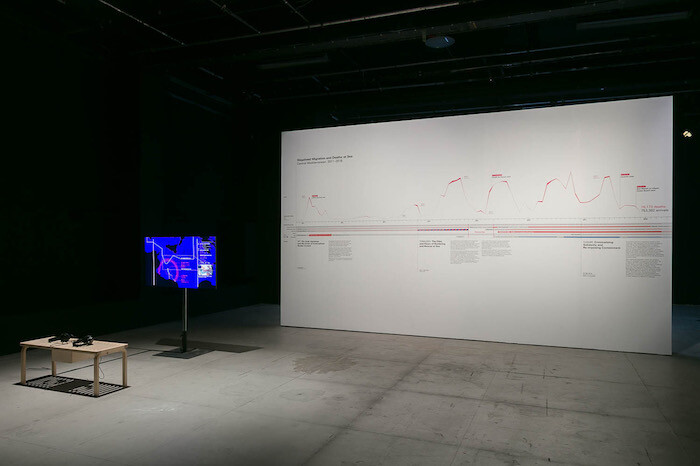

The resulting works are always in dialogue with absence—from physical absences (Drone Strike in Miranshah, 2013–16, a digital reconstruction using video testimony of a building destroyed by a drone), to absences of accountability (The Killing of Nadeem Nawara and Mohammad Abu Daher, 2014–15, in which sonic signatures of rubber-coated bullets are compared with live ammunition to determine if two Palestinian teenagers were unlawfully killed by Israeli soldiers). But the amount of information in the show can, by contrast, be distracting—there’s no avoiding it. In form and content, this exhibition is overwhelming.

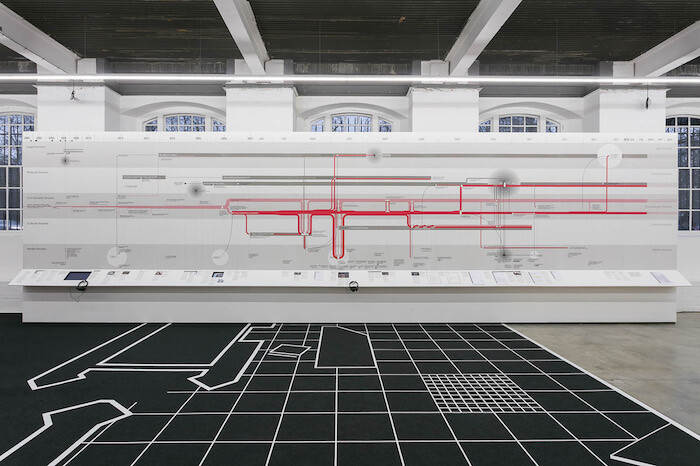

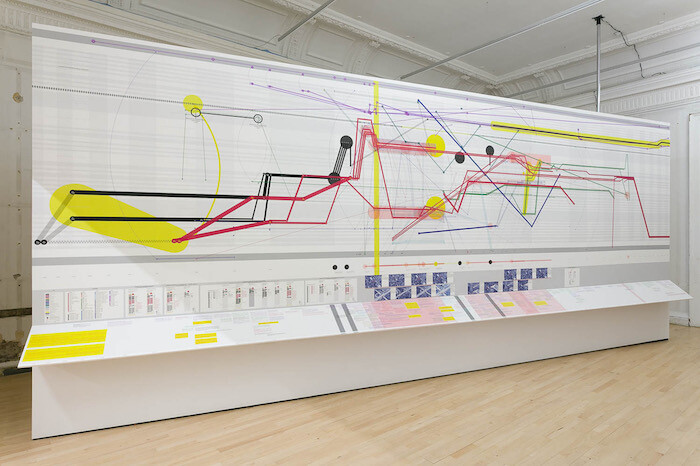

Take the large-scale mural The Forking Paths of Ayotzinapa (2017). This narrative timeline plots the police-enforced disappearance of 43 students in Iguala, Mexico, on September 26–27 2014. Red and black lines spike and diverge, intersecting with yellow beams and circles: a formally confusing and conflicting strata of data. I scan from left to right, then top to bottom, cross-referencing patterns of color with an accompanying key. A wall text explains this graphic juxtaposes the Mexican Federal Attorney General’s account of the event with conflicting ones extracted from survivors’ testimonies. Forensic Architecture describe the Mexican state’s destruction and falsification of evidence as “violence against people, but also violence against information.” Information—and the technologies that capture and store it—is given agency and weaponized. While the dense opacity of these visualizations evidence a failure to communicate clearly, they also suggest something more fundamental: the fallacy of “clear communication” when it comes to forensics.

Forensic Architecture’s investigations have appeared in courts and official inquires, but the group often presents its findings in an art context, notably at Documenta 14 last year and at their “Forensis” exhibition, made in collaboration with Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt in 2014. They define their work as “counter-forensics”—photographer Allan Sekula’s term for the adoption of forensic techniques by citizens to challenge the claims of the state. In its current incarnation, the ICA shares Forensic Architecture’s desire to repurpose power into public hands. ICA director Stefan Kalmár called in a recent interview for the organization to revitalize “civic responsibility in cultural institutions.”3 In this respect, the exhibition signals a mutually beneficial arrangement—one that attempts to re-imagine both forensics and art spaces.

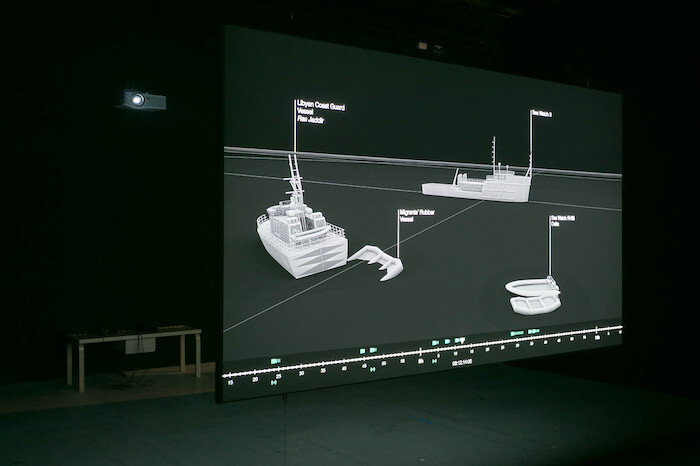

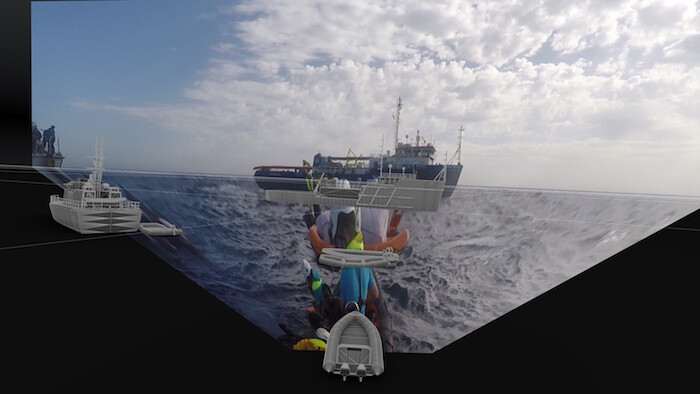

The practice of “counter-forensics” relies on material available in the public domain. Refused access to incident sites, in many of their cases Forensic Architecture analyze satellite images. Architect and academic Laura Kurgan describes the interpretation of such photographs as “an art, as well as a science.”4 The sharp binaries of subjective versus objective, art versus science, blur in the shared language of aesthetics. This intentional murkiness is evident in The European Union’s Lethal Maritime Frontier (2011–ongoing), featuring four investigations into migrant deaths in the Mediterranean over the last 30 years. Dramatically installed in the ICA’s theatre, an indigo monitor screen floats in a sea of black. A glowing white line darts from the Libyan coast, stops, veers back on itself: a scattering of green dots twinkle. This image depicts an overcrowded migrant boat drifting in distress, surrounded by commercial and military vessels, none of which intervene. In using surveillance technologies, Forensic Architecture co-opt “the master’s tools” to capture a crime of neglect.

After a while, I get stuck on the show’s reliance upon visual communication. Unlike the computer screen (much of Forensic Architecture’s work is available online), galleries allow for experimentation with sound, scent, and touch. Despite the group’s understanding of buildings as “sensors,” however, these installations fail to harness the exhibition as a sensory experience.

“Forensics” stems from the Latin forensis: “pertaining to the forum.” True to these etymological roots, the downstairs gallery hosts a short series of seminars. The sunken floor becomes a town square, the steps leading down to it seating. In his introduction to the “Forensic Aesthetics” seminar, Weizman stated that “a physical space allows for discourse and accountability.” It also exposes. Each display makes visible the methods by which Forensic Architecture assembles its cases, leaving them vulnerable to critique. These efforts at transparency feel generous. Despite my doubts, I want to believe him.

The Right Hon. The Lord Thomas of Cwmgiedd, Lord Chief Justice Of England and Wales, “The Future of Forensic Science in Criminal Trials,” The 2014 Criminal Bar Association Kalisher Lecture (14 October, 2014).

Eyal Weizman, Forensic Architecture: Notes from Fields and Forums (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2012), 10.

Stefan Kalmar, “In Profile: Stefan Kalmar,” interview by Paul Teasdale, frieze.com (February 10, 2017), https://frieze.com/article/profile-stefan-kalmar.

Laura Kurgan, Close Up at a Distance: Mapping, Technology, and Politics (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2013), 31.