At the time of his death in 2007, Jörg Immendorff was celebrated in his homeland as one of postwar Germany’s most famous artists, and also as one of its most infamous. Earlier that year the terminally ill, functionally incapacitated painter had directed a team of assistants to produce an official portrait of the former Chancellor Gerhard Schröder. The commission from Schröder, a friend of the artist, offered him a chance to redeem himself after a spectacularly louche scandal in which police found the wheelchair-bound Immendorff enjoying the company of seven prostitutes in a posh hotel suite, accompanied by some eleven grams of cocaine (on a Versace tray, no less). Whether because this rehabilitation was in fact successful, or more probably because Immendorff’s improbable escapade only enhanced his rakish reputation, a decade later the artist’s status in his homeland looks to be secure.

However, outside Germany matters are less clear. While Immendorff’s name is widely recognized, he has failed to attain the sort of superstardom associated with peers like Isa Genzken, Sigmar Polke, or Gerhard Richter, or even with younger artists like Martin Kippenberger. Although his work is in the collections of MoMA and Tate Modern, along with many other prominent museums, in the decade since his death he has yet to be the subject of a major international touring exhibition, leaving his place in art history somewhat uncertain.

The immediate explanation for this uneven reception abroad is that critical consensus on Immendorff’s oeuvre varies, most likely because he tended to buck prevailing tendencies or norms. His early art, which migrated from neo-Dadaist anti-aestheticism to explicit Maoist propaganda, could read to many as too extreme or uncompromising in its politics. More mature work like the series “Cafe Deutschland” (1977-82) might well have been found lacking in subtlety or irony, or were perhaps thought to be too German-specific for an international audience. The modest but carefully curated exhibition “LIDL Works and Performances from the 60s,” currently on view in New York at Michael Werner after stints in London and Berlin, makes a convincing case that Immendorff’s early output deserves closer consideration, not despite its many oddities and contradictions but because of them.

Some might argue that the artist’s earliest work, undertaken as a student of Joseph Beuys at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, should be dismissed as derivative juvenilia. But a more attentive reading reveals that it demonstrates genuine inventiveness, together with a strong contrary streak and a laudable indifference to risk. Like his teacher, Immendorff turned to intermedia performance as a means to flout high modernist doxa, but he quickly pivoted away from Beuys’s po-faced utopianism to develop forms of public action that were at once more militant and less tightly controlled.

This reorientation took place in the latter half of the 1960s, at the same time that the political and cultural landscape of West Germany was undergoing a massive transformation due to the ascendance of the New Left and the emergence of youth countercultures. At the beginning of this period Immendorff was mainly working in a faux-naïf mode, painting blithe cartoons of babies (Zwei gelbe Babies [Two Yellow Babies], 1967) and forest animals (Laufen [Running], 1965) while taking playful potshots at art world grown-ups like Beuys or the local gallerist Alfred Schmela (Blaue Punkte/Grüne Punkte [Blue Dots/Green Dots], 1965). The work has a kind of willfully immature, post-Pop sensibility; the precedents of Polke and Konrad Lueg are clear.

By 1969, Immendorff had staged several one-man protests at the national parliament building in Bonn; he had also helped lead a campaign against the leadership of the Kunstakademie, culminating in the occupation of the school and his expulsion. In addition, he had demoted painting to a supporting role in a practice that had jettisoned any conception of artistic autonomy, and was increasingly centered around making interventions in the world outside the gallery.

The Werner exhibition usefully reminds viewers that Immendorff also studied with the Swiss stage designer Teo Otto, who had supervised set design for productions of Bertolt Brecht’s work in Berlin and Zürich during the Nazi era. Aspects of this legacy are evident in the fact that much of Immendorff’s early work was produced for the express purpose of breaking whatever vestiges of the fourth wall might have remained in extra-theatrical performance.

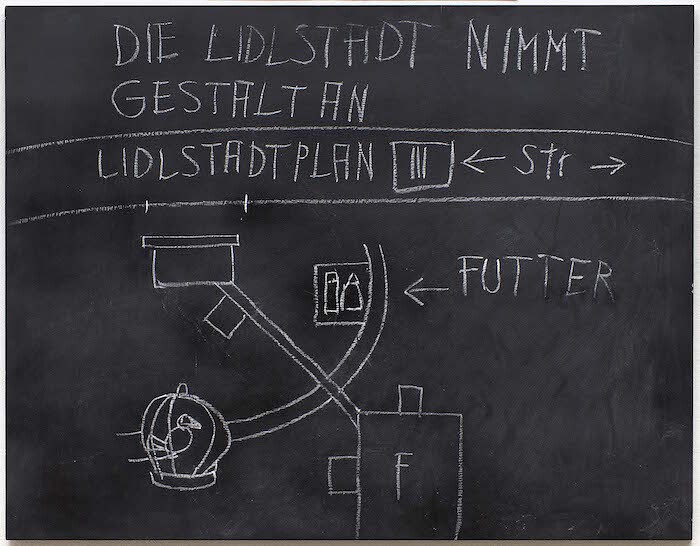

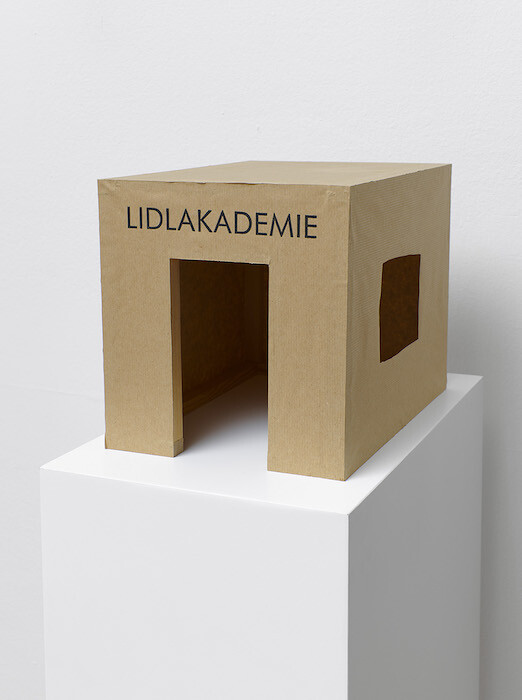

Many of the materials on view at Werner are essentially homemade props: a LIDL flag like the one flown from the roof of the occupied Kunstakademie (LIDL, 1969); sportswear for the LIDL Olympiad (100 Meter Lauf [100 Meter Run], 1969); the wooden LIDL-Block (1969), painted in the colors of the West German flag, that Immendorff used in one of his crypto-absurdist protests at the Bundeshaus. None of these objects is artfully made; instead, they exude the kind of unschooled, everyone-is-an-artist stylelessness that more recent artists like Thomas Hirschhorn have used to try to dehierarchize the entrenched class stratifications of the art world.

Like other openly leftist Western European artists, Hirschhorn is often reflexively compared to Beuys. Yet such parallels can obscure other important genealogies, like the one Immendorff’s LIDL period suggests. Partly because Immendorff and his collaborators lacked Beuys’s notoriety—but also because they eschewed his tendency to mix politics with myth-making, media events, and his own cult of personality—they were able to execute events that were more seamlessly integrated into everyday routines, and therefore more subtle, unexpected, and confounding. The most powerful LIDL actions don’t read clearly as either performance art or radical politics; they somehow manage to combine pathos, absurdity, and conviction. In this sense, they have less in common with Beuys than with Vito Acconci, Adrian Piper, or even Andy Kaufman.

What is arguably most important about the LIDL work is that it further radicalized the potential of the ascendant non-aligned left, and that it did so in ways that productively articulated aesthetics and politics. Unlike the German Student Party or the Organization for Direct Democracy—independent parties that Beuys largely organized around himself (and which also helped enable the formation of the Green Party in 1980)—LIDL represented a model of non-governmental politics, one that was laterally organized and focused on more direct forms of engagement. LIDL was distinctively scrappy and ad hoc, either anarchistic or just anarchic; it makes no sense to call it an “organization.”

With that said, the group helped initiate the reform of the Kunstakademie and sought to forge alliances between art students and the national artists’ union. LIDL opened what would now be called an artist-run space in Düsseldorf, where it held teach-ins on global insurrection and hosted performances by Nam June Paik, Charlotte Moorman, and the Spanish-Italian Fluxus-aligned Zaj group. It helped organize an occupation of a central public plaza in efforts to mobilize tenant activism.

As Immendorff’s politics shifted further left (in 1970 he joined a Maoist sect, the League Against Imperialism), he came to think that his position within the group had failed to overcome the petit-bourgeois character of the artist’s authority. He returned to painting, adopting a seemingly unironic, heavily didactic, figurative style that reframed the medium as a vehicle for the realization of Marxist praxis; he also spent 11 years as an art instructor in public schools, where he came to be known as a fantastic teacher.

What sense did it make for Immendorff to negate his earlier anti-aestheticism by essentially appropriating Socialist Realism? How can this turn be reconciled with his earlier absurdism, irony, and obliquity, or with his later incarnation as a farcically grandiose, Teutonic Dionysus? And what sort of relation existed between these tensions in one artist’s practice and the evolving structural contradictions of postwar West German society?

While the Werner exhibition doesn’t highlight these questions as clearly as it might, neither does it shy away from them. The show is not without its own contradictions, the most obvious of which is its attempt to retroactively designate Immendorff’s makeshift props as masterworks, transforming them into collectible luxury goods, even relics. All the same, it suggests that the articulation of aesthetics and politics should not be regarded as a given, but as a problem, a question, and a struggle; an opportunity but also in some sense an obligation. Over and against the unimaginative pieties of “committed art,” practices like Immendorff’s can still serve as examples of how such connections might work and what they might yet be able to do.