The most useful warning ever given to me while studying the Parisian avant-garde was “don’t forget they were all sleeping with each other!” A vital reminder that modern art was not the product of a pure and original creative act, but rather the consequence of cross-pollination that occurred thanks to friendships, sexual relations, and confrontations. That idea of purity and originality, still often fed to modern art scholars like mother’s milk, is a construction deeply compromised by power, politics, and, yes, sexuality. This context is inescapable, especially when wandering through FIAC at the Grand Palais. A leftover of the Exposition Universelle of 1900, the Grand Palais is a paradigmatic example of how France displayed its hegemonic power over culture and technology.

As a scholar of feminism and decolonialism, I am determined to deconstruct the canon I was handed. I resolved during my visit to focus on practices that signal a transformation in mainstream narrative and to ignore outdated (albeit seductive) presentations dedicated to contemporary mainstays, or booths like Gagosian’s all-male display dedicated to artists who spent time on the French Riviera. My main inquiry is, how are artists articulating the notions of impurity, disjunction, difference, and desire this week in Paris?

Zineb Sedira’s work Scene 3: Way of Life (2019), produced for her exhibition “A Brief Moment” at the Jeu de Paume, is a diorama of the artist’s living room, which visitors are welcome to sit in. Sitting on the sofa, they can read transcripts from the first Pan-African Festival held in Algiers in 1969, or watch the euphoric account of a woman remembering the Festival that took place when she was 17 years old. Bearing in mind that the first Pan-African Congress took place in Paris in 1919 with delegates from 15 countries and colonies, the Festival in Algiers 50 years later was the first initiative of its kind to be held in North Africa and it marked the desire for liberation from imperialism and racial inequality after the crumbling of the French colonial empire. Making a strong case for decolonial art, Sedira locates vivid desire for liberation across time, between the 1960s and the present day, begging the question: To what degree have things changed?

The first display at FIAC to strike a chord with my mission to see difference and desire was Sāo Paulo gallery Mendes Wood DM’s solo presentation of oil paintings by Antonio Obá, whose work confronts his difficulty in asserting his non-normative subjectivity as an Afro-Brazilian man. His subject matter ranges from personal anecdotes to historic episodes of civil rights activism to religious syncretic imagery. In Mero Aprendizado [Mere Learning] (2019), Obá depicts a smiling figure holding a platter with a severed head on it, making a reference to both the sacredness of ex-votos, often in the shape of severed body parts, and the biblical stories of Salome or of Judith severing the head of Holofernes. Linda Nochlin has argued that after the French Revolution the dismembered body, especially the guillotined head, became a metonym for the very idea of revolution, which shows how Obá is using this imagery to carve out space within a traditionalist Catholic history.1

Dealing with the exclusions of history is also the artist and feminist writer Mira Schor, represented by New York’s Lyles & King (whose stand at FIAC is the artist’s first substantial presentation in Europe). In Hairy Semi-Colon (1993), she depicts a punctuation mark, a silent symbol that determines a pause, but not an interruption. By surrounding it with fleshy paint and pubic hair–like brushstrokes, she conjugates a formal investigation into the medium of painting with feminist research into new forms of language that challenge phallogocentrism. In simpler terms, she connects body and language.

There is a remarkable visual link between this sense of visceral fleshiness in Schor’s use of oil and Mandy El-Sayegh’s exhibition “White Grounds” at Bétonsalon, in which El-Sayegh transformed the single room the exhibition occupies into an immersive environment with tapestry-like canvases hanging and overlapping on the walls accompanied by an open metal vitrine gathering the source materials for her paintings—photographs, clippings, faux-organs, and found objects. Most strikingly, the floor is tiled with rectangular sheets of latex, which completely alter the way visitors walk and feel in the space.

A connection between language and body is also central in Sarah Tritz’s exhibition “J’aime le rose pâle et les femmes ingrates” [I love pale pink and ungrateful women] at the Contemporary Art Centre of Ivry – Crédac. Alongside her own works, Tritz invited 29 other artists to participate in the show, which she says connects two forms of pleasure: “erotic pleasure strictly speaking, that is, glamour; and cognitive pleasure, that it, grammar.”2 Liz Craft’s sculpture Me Princess (2008–13), a sinister naked female figure seated with her legs open with bright red lips, nipples, and vulva, is displayed staring straight at Tritz’s Pulpe espace (2017), a deep-red enameled ceramic oval (the artist’s take on Lucio Fontana’s “Concetto Spaziale” works). The show concludes with a screening of Ellen Cantor’s sexually explicit video Club Vanessa (the London Tape) (1996), in which she tests the boundaries of polyamorous relations, gender, and love, practicing a détournement of some of the devices of pornography.

The notion of the boundary is addressed by Kiki Smith’s solo exhibition at La Monnaie de Paris. Following no specific order, the exhibition fluidly takes viewers on a journey through Smith’s cosmology of references: from casts of human organs to monuments to witches burned at the stake, and humans merging with animals or coming out of them. In homage to the city of Paris is the depiction of Saint Geneviève (the city’s patron saint, traditionally surrounded by sheep and wolves) as a nude figure emerging out of a wolf (Sainte Geneviève, 1999). In addition to a reference to Little Red Riding Hood, I prefer to read this work as the embodiment of trans-species kinship, an interpretation indebted to Rosi Braidotti and Donna Haraway. Over at Paris Internationale, a fair characterized by much bolder and experimental displays and performances, local gallery Sans titre (2016) showcased works by Robert Brambora, who also presents an inquiry into trans-species relation. His silhouettes of heads kissing are filled in with animals (dogs) and plants. His overlaying of the human with the flora and fauna, simply but beautifully forwards the idea of love across taxonomic boundaries.

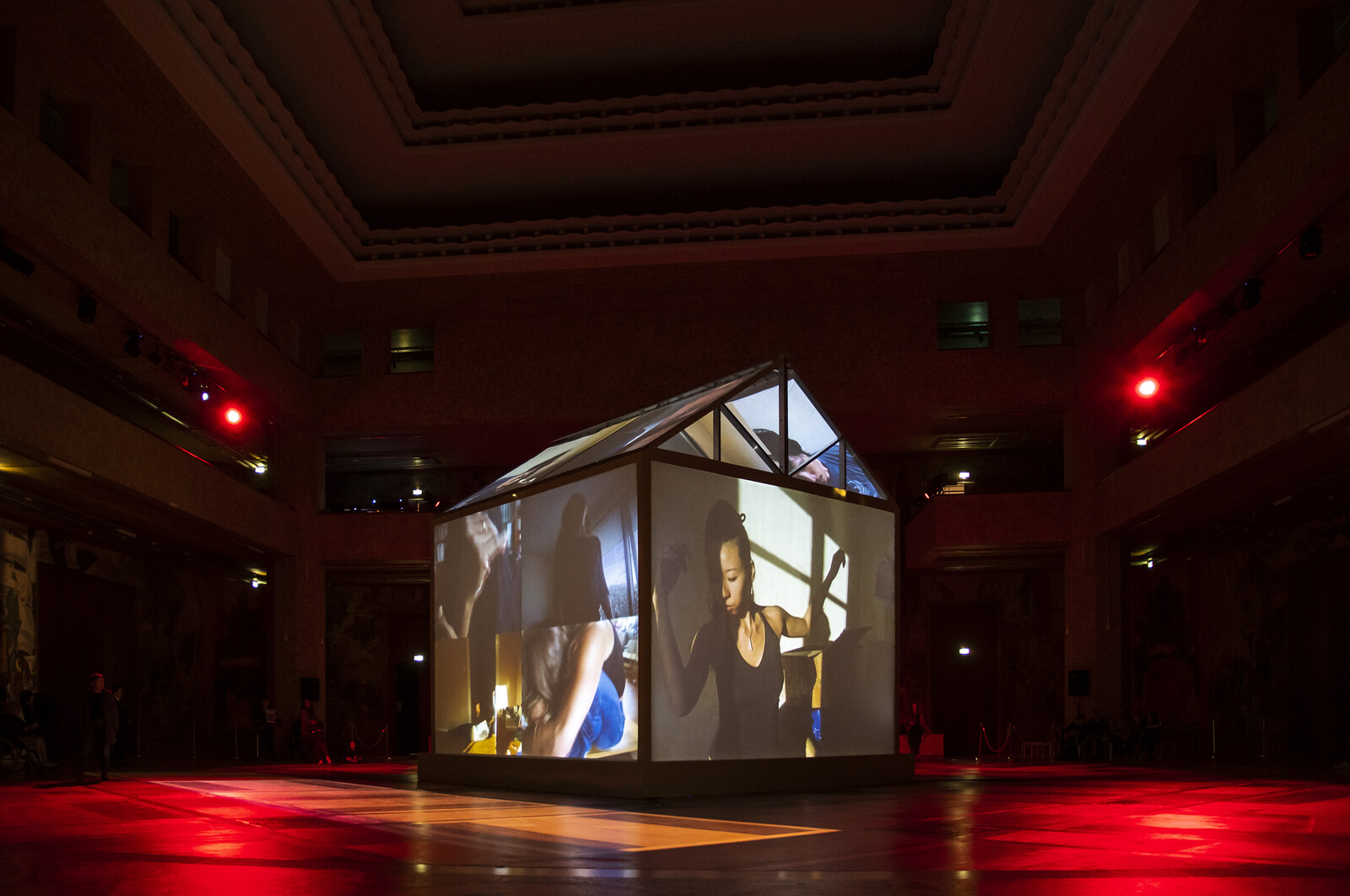

I found a corollary of my itinerary in La Zon-Mai (2011–ongoing) by choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui and artist and film director Gilles Delmas at the Museé national de l’histoire de l’immigration. The work is a monumental house-shaped structure onto which a mosaic of 21 looped videos are projected. In each video, professional dancers who experienced displacement or migration were invited to reflect with their body on the ideas of habitation, home, and belonging. The resulting videos, filmed in the actual home of each dancer, show us the point of union between the body’s unregulated spontaneous movement and the assertion of subjectivity, through the idea of home. Located in such a connoted space, this work underscores the potential of culture to liberate minds and bodies.

Linda Nochlin, The Body in Pieces: The Fragment as a Metaphor for Modernity (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1994).

Sarah Tritz, exhibition guide, “J’aime le rose pâle et les femmes ingrates,” Contemporary Art Centre of Ivry – Crédac, 2019.