“Ecological turns” is a series in which writers from different fields of the ecological discourse consider new ways of making and responding to art. In this instalment of the program, which is co-commissioned with Filipa Ramos, the novelist and historian of science Daisy Hildyard reflects on the work of Anicka Yi.

I recently came across a poem that I found unsettling. I was reading Oli Hazzard’s Blotter and the voice appealed to me: it spoke in a direct way but the course of speech kept changing. There were images of sprouting seeds, cherry brandy, people kissing and whispering, Ukrainian coal imports, wandering deer. There was something that felt right about this jumbled reality, and something vulnerably human in the intimate experiences it alluded to: lips burned on hot tea, the fear of the dark wood, drowsiness, the pleasure of reading aloud. This is how the world feels, I thought. And then I read the book’s blurb, which explained that the lines I had found so characterful were generated by a Russian spambot. This was a speaker who could not grow drowsy, or burn its lips on tea.

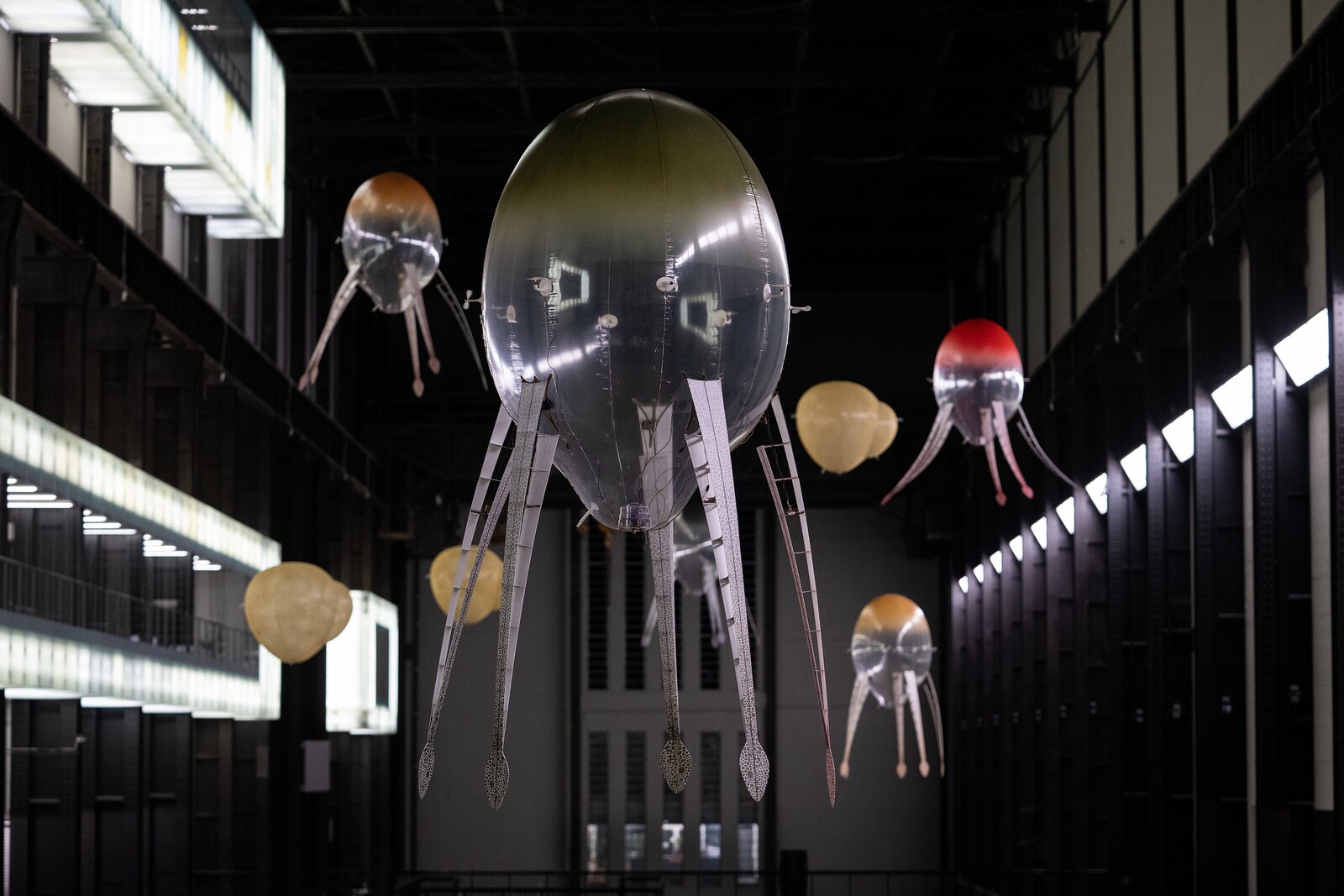

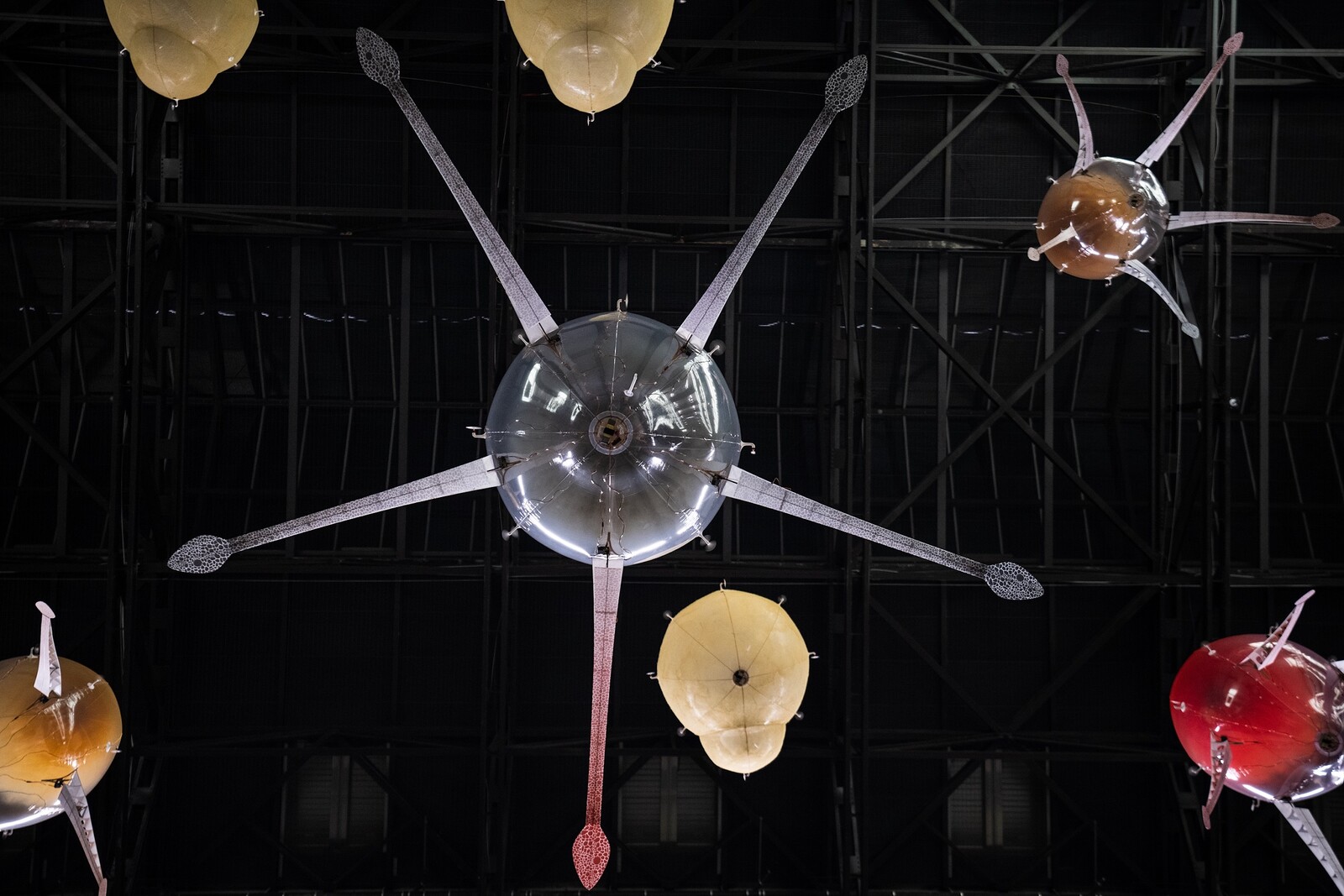

My response to the poem, no doubt, says something about my own emotional intelligence—but more interestingly, I wonder what it says about the bots. I thought about it again when I spent time with Anicka Yi’s aerobes, skyborne robots that floated in Tate Modern’s turbine hall until February 6. Monday morning, early January. Two women with young babies in highly engineered pushchairs circulated, separately, in the quiet public space. The women glanced up, every now and then, at Yi’s installation, which had opened up another space: a volume of air below the ceiling. The babies were transfixed.

Large balloon-like translucent forms drifted above us. Some looked like cephalopods, with giraffe-patterned tentacles, and a spill of color—rose pink, bottle green, dove gray, rust—over their faceless heads. Others were bulbous and appeared to be covered with brackish moss or fine hair. They all had an ancient look: their surfaces were dirtied, like thumbed paper or something washed up on the beach, but there was also something newborn about them, all thin membrane and glowing color. Mostly, they hovered together around the glassed-in viewing platform, moving gently, making breathy noises. From the lower floor I saw the people on the viewing platform as part of their shoal or swarm. I did not see the aerobes collide, and wondered how they sensed one another. Their mechanisms weren’t concealed: wires as fine as blood vessels, and tiny propellers like the toy fans that people use on the underground in summer. Yi has described the work—it, them—as machines that have come to life through incremental technological developments. They were speculative life forms, evolving inside the gallery as they responded to one another and to the air.

Sharing space with these beings wasn’t inherently good or bad. They were intimidating and compelling, with the primal, wise old presence that new creatures often have. They embodied unexpected syntheses. Insect swarms, plastic fans. Membrane, wiring. Savannah camouflage, reef tentacle. As organisms they’re aliens. Part for part, they’re of the earth. I thought about an essay, “Immortality” (1978), in which Jorge Luis Borges imagines components of a person circulating beyond death. Borges is uninterested in personal immortality of name or body, “I want to be free from all that.”1

Instead, he has faith in what he calls “cosmic” immortality, wherein traces of a life are animated across beings. The immortality of Christ arises each time a person loves an enemy. Reciting a line of Dante or Shakespeare means actually becoming “that instant when Dante or Shakespeare created that line.” We can all dwell in this extended or prosthetic way—we all do—because “every one of us collaborates, in one form or another, in this world.”

Borges’s ideas about mortal existence in the 1970s helped me, half a century later, rethink this atmosphere in which Yi’s organisms are suspended. Everything is hybrid here. Any mechanism—an aerobe or an overengineered pushchair—is imbued with fears and hope. A spambot’s script comes pre-soaked in feeling because it is made of human technologies, including language. And reciprocally, cute robots and soulful programmed scripts are inducing and shaping thoughts and emotion. It’s a truism to say that we are all robots now: Human bodies augmented with prostheses; identities comprised of organic flesh in combination with virtual avatars, verified by facial and fingerprint scanners. Each new technology has its political life. They all reflect or, occasionally, disrupt the prejudices and inequalities of the environments in which they come into being. Machines stream through bodies, pacemakers, and microchips, and through thoughts, shaping opinions and unsettling experience. You are an aerobe: a new life form, floating in an estranged political space, no longer contained by hard borders between human and machine, information and feeling, life and nonlife, by the boundaried organic body, because you’re free from all that now. What next?

Jorge Luis Borges, “Immortality,” Selected Non-Fictions, ed. Eliot Weinberger (New York: Penguin Putnam, 1999), 483–91.