The first thing I saw upon entering the tent at Frieze New York was Elmgreen and Dragset’s Rite of Passage (2014) at Massimo De Carlo, a tattered sign bearing the word “MIRACLE” with a white vulture perched on top, flanked by lengths of torn chain link fence. This dismal tableau fitted the mood: when I left my apartment for the preview on Thursday morning, Congress was, for the second time in as many months, debating a bill that would return millions of Americans—including most of the artists and writers I know—to the ranks of the perpetually uninsured.

This unreal quality of the fair, literally ensconced on an island, was the subject of Dora Budor’s Frieze Projects commission, MANICOMIO! (2017), for which she hired several Leonardo DiCaprio impersonators to meander around in the guise of the actor-collector’s notable characters. Details were left intentionally murky in the advance press materials, presumably to enable moments like the one I experienced upon seeing a man with a scraggly beard and fur cape walk by: I jotted down in my notebook “is the man dressed like he belongs in The Revenant a performance artist, or just weird?”

Still, I was pleased by the distraction. Though the overall atmosphere of the fair was subdued, even anxious, explicit references to the dire state of world politics were few and far between. When they appeared, I found them mostly facile and unwelcome: Paris/Brussels Galerie Nathalie Obadia brought a selection of large-scale photographs from Andres Serrano’s “America” series (2001-04), a collective portrait of the nation through a catalogue of its stock types. Occupying the role of grotesque tycoon is Donald Trump, photographed in 2004, back when he was merely an obnoxious celebrity. His smug pout was given pride of place at the center of the booth, bracketed by portraits of Snoop Dogg (Snoop Dogg, 2002) and a young Mexican migrant worker (Cheneke Nanaoxi, Mexican Migrant Worker, 2002)—a cheap attempt at ironic political commentary.

Also largely absent were the sorts of selfie-friendly oddities normally trotted out at fairs. (The presence of neons, normally an art fair staple, was confined to a single booth, Pace Gallery’s solo presentation of recent light sculptures by Keith Sonnier.) Instead, galleries tended towards smaller, subtler works that rewarded close looking, which was equally refreshing and frustrating; I saw any number of things I wished I could return to in a more forgiving environment. Even Gagosian opted to fill its behemoth booth with a salon-style hang of dozens of little drawings and sketches by John Currin in lieu of paintings. Nearby, David Zwirner divided its booth into two mini solo shows, with one half featuring photographs by William Eggleston, and the other several exquisite new assemblage sculptures by Carol Bove made from contorted pieces of found steel painted in primary colors (such as Prélude à l’aprés-midi d’un faune, 2017). New York/LA’s Matthew Marks displayed three small, charming ceramic sculptures by Ron Nagle (Young Throng, 2016; Hardy Plank, 2014; and Exposed Prosthetic, 2016) on individual plinths placed around the booth, giving them plenty of room to breathe. I was similarly taken with a series of wall-bound sculptures constructed from found refuse that alluded to the forms of African masks by Romuald Hazoumè, at the booth of London’s October Gallery (among them Passe Temps, 2015 and A mi chemin, 2016). Though Blum & Poe’s booth was a more typical art fair mishmash of gallery inventory, it included my favorite work of the day: Henry Taylor’s Deana Lawson in the Lionel Hamptons (2016), a portrait of his Whitney Biennial neighbor kneeling casually in a sundress, the title suggesting a covert dig at the fair’s collector class denizens.

That’s not to say that ambitious booths were altogether absent: the Frieze Stand Prize-winner, New York’s PPOW, brought together street-art inflected works from the downtown New York scene of the 1980s—Martin Wong, Charlie Ahearn, David Wojnarowicz—alongside a recreation of Anton van Dalen’s installation The Pigeon Car (1987), a pigeon coop with live birds in the shape of a car (the artist has maintained his own rooftop coop in the East Village for decades.) A few booths over, another New York gallery, Canada, decided to embrace the eclectic booth principle, allowing Marc Hundley to arrange small paintings, prints, sculptures, and books by his fellow gallery artists within a pseudo-domestic interior modeled after his own studio apartment, replete with a bed, couch, and shabby carpets.

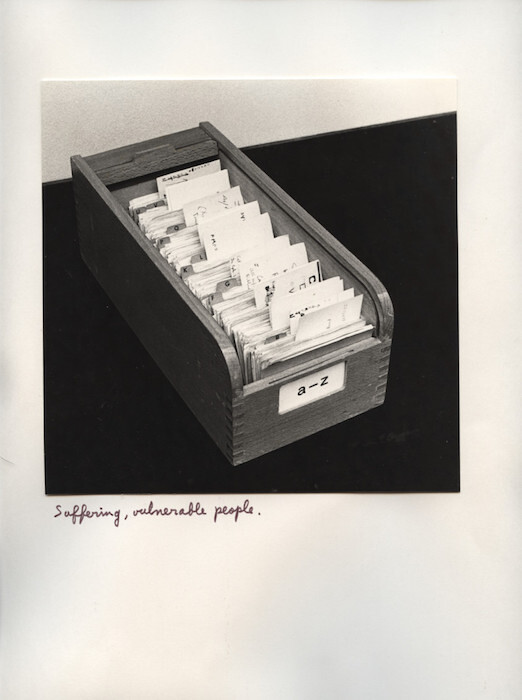

As is often the case with Frieze, the highlights of the fair were mostly found in the sections devoted to smaller galleries with tightly curated booths. In the Frame and Focus sections, selected by curators Jacob Proctor and Fabian Schönleich, Warsaw’s lokal_30 brought an intergenerational trio of Polish women artists. A grid of photographs from pioneering feminist conceptual photographer Natalia LL’s series “Sztuka Postkonsumpcyjna” (Post-Consumer Art, 1975) and “TAK/YES” (1971) was placed alongside Zuzanna Janin’s video Walka/Fight (2001)—in which the artist boxes the professional heavyweight Przemysław Saleta—and new paintings by the emerging artist Ewa Juszkiewicz based on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century society portraits. Walden Gallery, from Buenos Aires, brought a series of spare conceptual works on paper from the 1970s by Ulises Carrión, with a vitrine of fascinating ephemera related to his work as an artist, publisher, and poet at the center of the booth.

In the Spotlight section, devoted to solo presentations of historical works, Brooklyn’s Southfirst brought a selection of performative photographs by Jared Bark, made between 1969 and 1976, for which he employed the predetermined grid of the automatic photobooth strip, reprising the gallery’s recent critically acclaimed exhibition of the artist. Honor Fraser, Los Angeles, featured early works by Kenny Scharf, including an array of psychedelically painted consumer electronics—boomboxes, answering machines, and blenders—from the early and mid 1980s. New York’s Bruce Silverstein Gallery’s booth was dominated by the massive three-panel mural Americans, Youngstown Ohio (1977-78) by Alfred Leslie, a stark, realist portrait of the town’s residents painted shortly after the closure of a factory anchoring the local economy. I disliked the painting, with its dour palette, ungainly figures, and shallow humanism, but admired the gallery for bringing something so insistently unfashionable.

Though I am reluctant to complain about thoughtfully arranged booths highlighting works by older, under-recognized artists as an art fair trend, another word for it might be “safe.” Though there was certainly examples of engaged art on view, those works were mostly made in response to crises of the past: AIDS, the Civil Rights movement, the Cold War, and so on. From a commercial standpoint, work by regionally influential postwar artists from, say, Latin America or Eastern Europe, who have rarely exhibited abroad satiates collectors’ desire for the new and unfamiliar without any of the risk of emerging contemporary art. Or maybe everyone just wanted a temporary escape. By the time I returned home, the bill had passed the House. It seemed like the wrong moment to be at an art fair.