The work of the American artist Bruce Conner—dime-store assemblagist, quick-splice cineaste—is too little seen in the UK, and so we should be grateful to Thomas Dane Gallery for their recent periodic exhibitions of his work, each focused on a single film. Following CROSSROADS (1976) in 2015 and A MOVIE (1958) in 2017 comes BREAKAWAY (1966): three films from three different decades. Their achronological presentation seems appropriate, given Conner’s fascination with the temporal shifts which film afforded him.

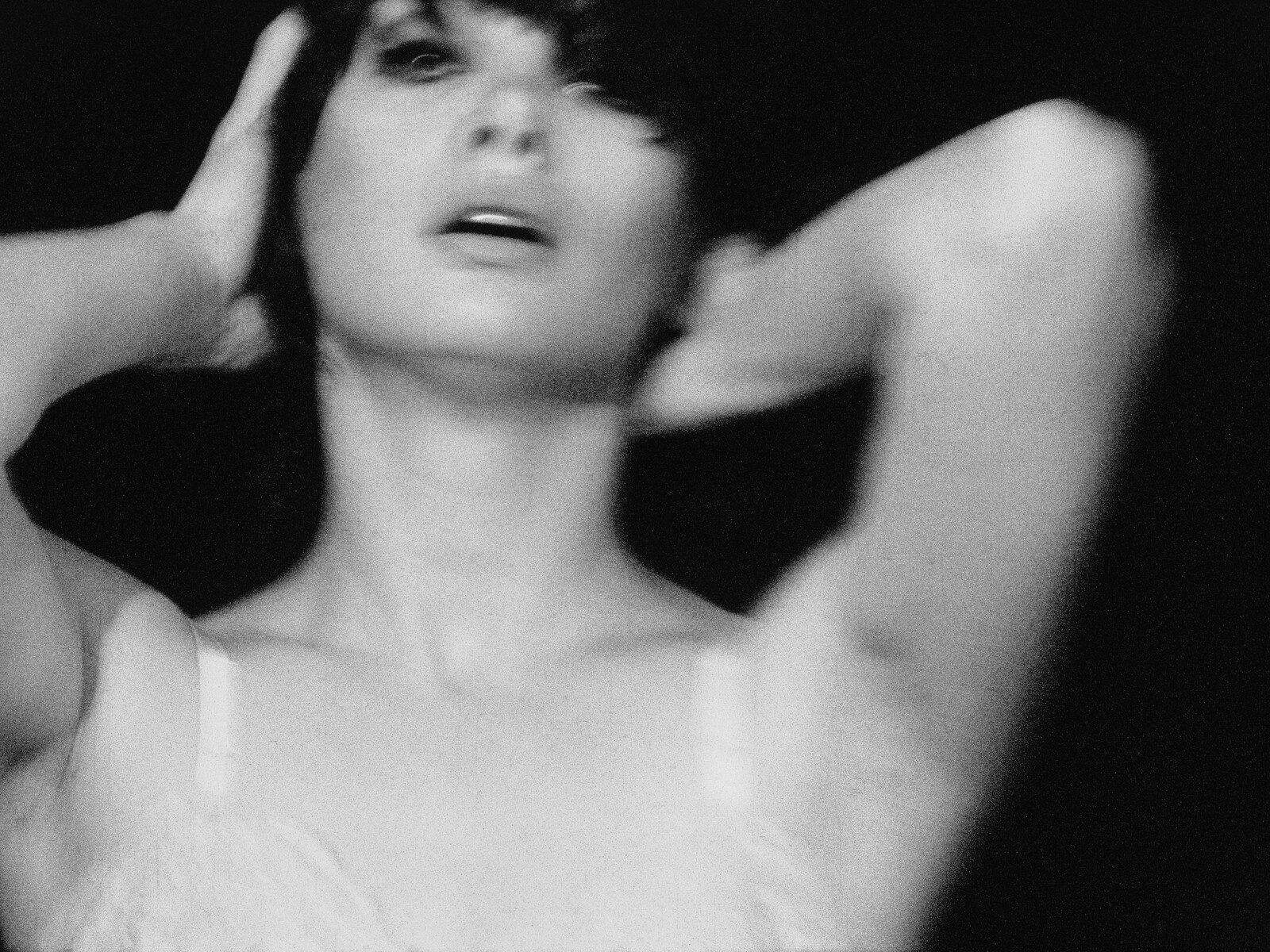

While BREAKAWAY shares some of the concerns of these other films—such as the destructive impulses of desire and the emptiness that lies at the center of things—it is in many respects the simplest of the three. It is also the only one made from footage Conner shot himself, rather than material found from other sources. The location was a collector’s house in Santa Monica. Conner’s friends, the actors Dean Stockwell and Dennis Hopper, held the lights, and the subject was Antonia Christina Basilotta, a young singer and choreographer whom Conner had met through Stockwell and artist Wallace Berman. The five-minute film opens with a flickering image of Basilotta posing against a black background, dressed only in a black bra and black tights into which holes have been cut, like a peep-show Yayoi Kusama. After a few seconds the music starts: the B-side of the titular single released in February 1966 under her stage name Toni Basil, a driving, high-tempo track which sets the pace for the film. Basil’s dancing is lively, but through Conner’s quick-zoom camera and stroboscopic editing it becomes almost frenetic, her underwear changing—then disappearing—in the blink of a camera’s gate. Just over two minutes into the film, as the song fades and the screen goes black, the film plays in reverse, sound and vision, from its end to its beginning.

If dance has long made use of film’s ability to record its movement—think of Loïe Fuller’s “Serpentine Dance” almost captured by Léon Gaumont, the Lumière brothers, and Georges Méliès in the 1890s—then it has also harnessed film’s mechanisms to create impossible movements, such as the leap made by Talley Beatty in Maya Deren’s A Study In Choreography For Camera (1945), in which a jump cut allows him to leap from one place to another, from museum foyer to forest floor. The disjunction of time and space delighted Conner, and the seemingly simple act of reversal necessitates our asking what it was, exactly, that was going forward? Here, it is an assemblage of fragments held together by splicing tape and a 4/4 beat.

In 1973, Conner described the impact of Alain Resnais’s Last Year at Marienbad (1961)—“Time, space, breakup, past, future, bits and parts of concepts and still photographs”—and this might be considered a concise description of BREAKAWAY, too, even if it makes absent something else which both films share: a coolly displaced eroticism. Basil’s Breakaway is an upbeat anthem to social and sexual liberation, but BREAKAWAY is rather less certain. Yes, the film presents Basil in a particular way, with her oh-my-God eyes and a fringe like a lowering veil, but Conner’s frenetic vision of her denies the more immediate straight male pleasures pervading the culture of the time, whether pop or Underground, where a woman’s liberation was most often merely a different form of subjugation.

The dancing figure is clearly sexualized, but Conner distances her from the viewer with whip-zooms and shifting frame rates. As in much of his work, especially the films Cosmic Ray (1961) and Marilyn Times Five (1968–73), Conner encourages certain desires while alienating them also, getting them to flicker like his edits, dazzling and disorientating, turned on then off, off then on. It is utterly captivating, and we are not the only ones who are caught: as the film goes on, and turns back, Basil does not—cannot—break away, but is pulled around, and returns inexorably to the place from where she began. Her liberation is only momentary, and flittingly incomplete.