I didn’t think I’d be this excited to go back to a gallery. In some ways, I’ve enjoyed experiencing art within the confines of my Brooklyn apartment over the past months, and I’m still excited by the possibilities arising from the advent of novel digital platforms. But this time away from real-life art viewing has made the experience a novelty, and as galleries started to reopen it felt like a much-needed indulgence—after months of social distancing, and then weeks of defying said social distancing to protest in the streets against the most recent examples of state-sanctioned violence against Black bodies—simply to be back.

At “Jack Whitten. Transitional Space. A Drawing Survey.” at Hauser & Wirth on the Upper East Side—an exhibition which outlines Whitten’s exceptional works on paper chronologically, from the 1960s to the 2010s—I was surprised by the boyish glee I felt just at noticing the pronounced physicality of paper: the deckled edges, the wrinkle in the page, the raised contours of paper cut-outs collaged onto another flat surface. The show demonstrates the careful evolution in Whitten’s work from figuration to abstraction, but also focuses on the artist’s attention to material, and the various techniques that make his later drawings feel almost sculptural. Site #2 (1986), made during a period where Whitten was exploring the connective threads between the seemingly opposed realms of advanced technology and spirituality, is a delicate work made with sumi ink and acrylic on rice paper. The thin, translucent sheet is heavily marked with black ink and white paint, formed and crumpled to resemble a 3D topographical map, perhaps showing a dark, snowy mountain range—effectively turning something so weightless into solid form.

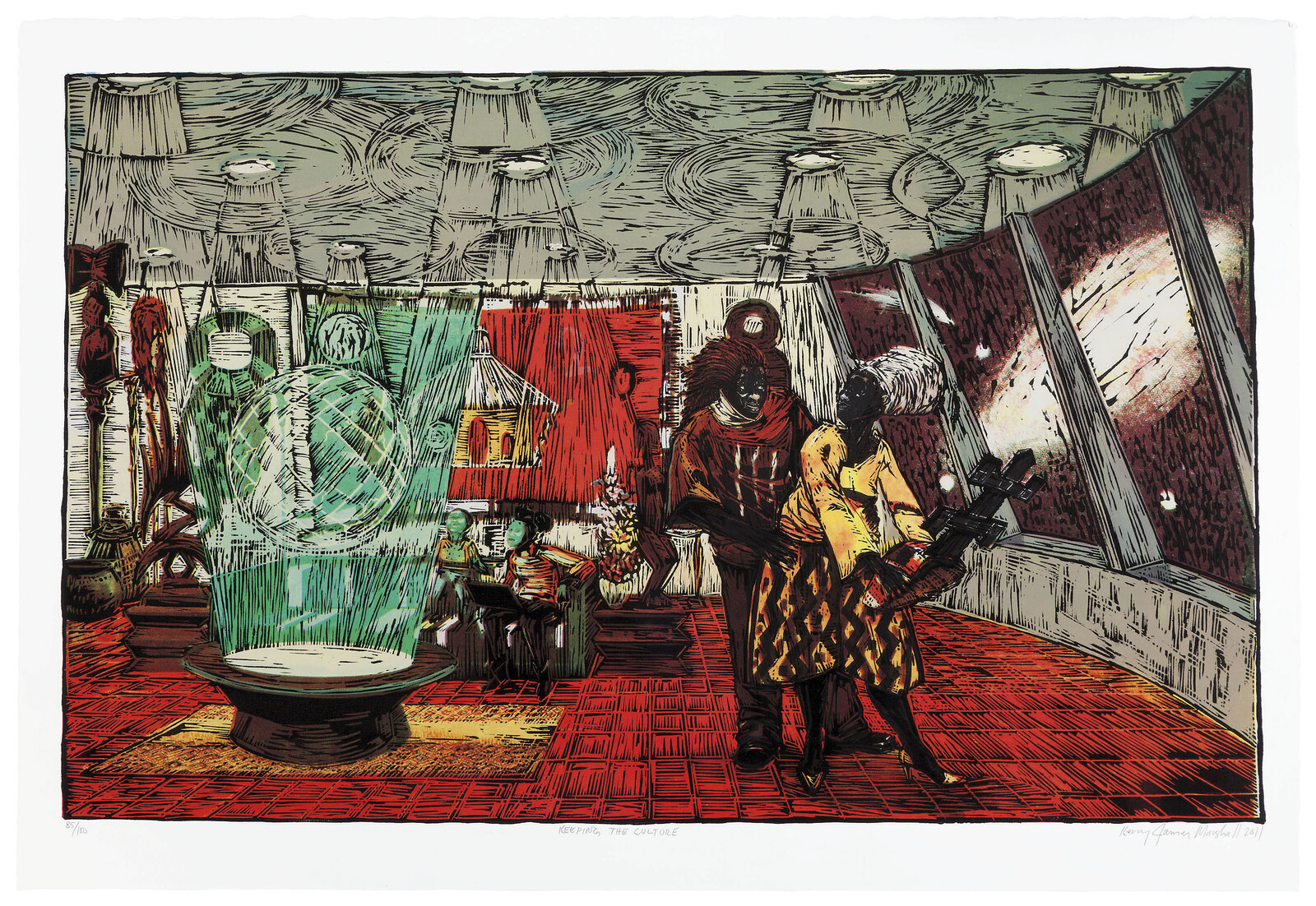

The group show “Young Artists: One” at Fridman Gallery also showcases works that call attention to their own materiality. On display is a diverse selection of works on paper, paintings, and sculpture from 33 different artists, among them Kerry James Marshall, Lorna Simpson, Alteronce Gumby, Amani Lewis, and Al Loving. Nanette Carter’s colorful abstractions—oil on sheets of Mylar that are layered over each other with different textures and color patterns—stand out as sculptural paintings, often mounted on foam board to enhance a sense of form and volume. Nate Lewis achieves a similar effect in his work, which takes inkjet prints of photographic images and manipulates them through frottage, a technique that reveals the white of the paper and creates a more textured surface. In Probing the Land II (2019)—part of a series of works that looks at problematic American monuments—Lewis presents an image of the equestrian relief of William Jenkins Worth, a general in the Mexican-American war, whose mausoleum is located just outside of Madison Square Park in New York. Lewis uses frottage on the limbs of General Worth and his horse, forcibly abating the hardness and significance of the bronze plaque. His process of eviscerating the figure’s charisma and presence as a war hero through mark-making recalls the recent acts of public protest that have seen Confederate monuments splattered in paint.

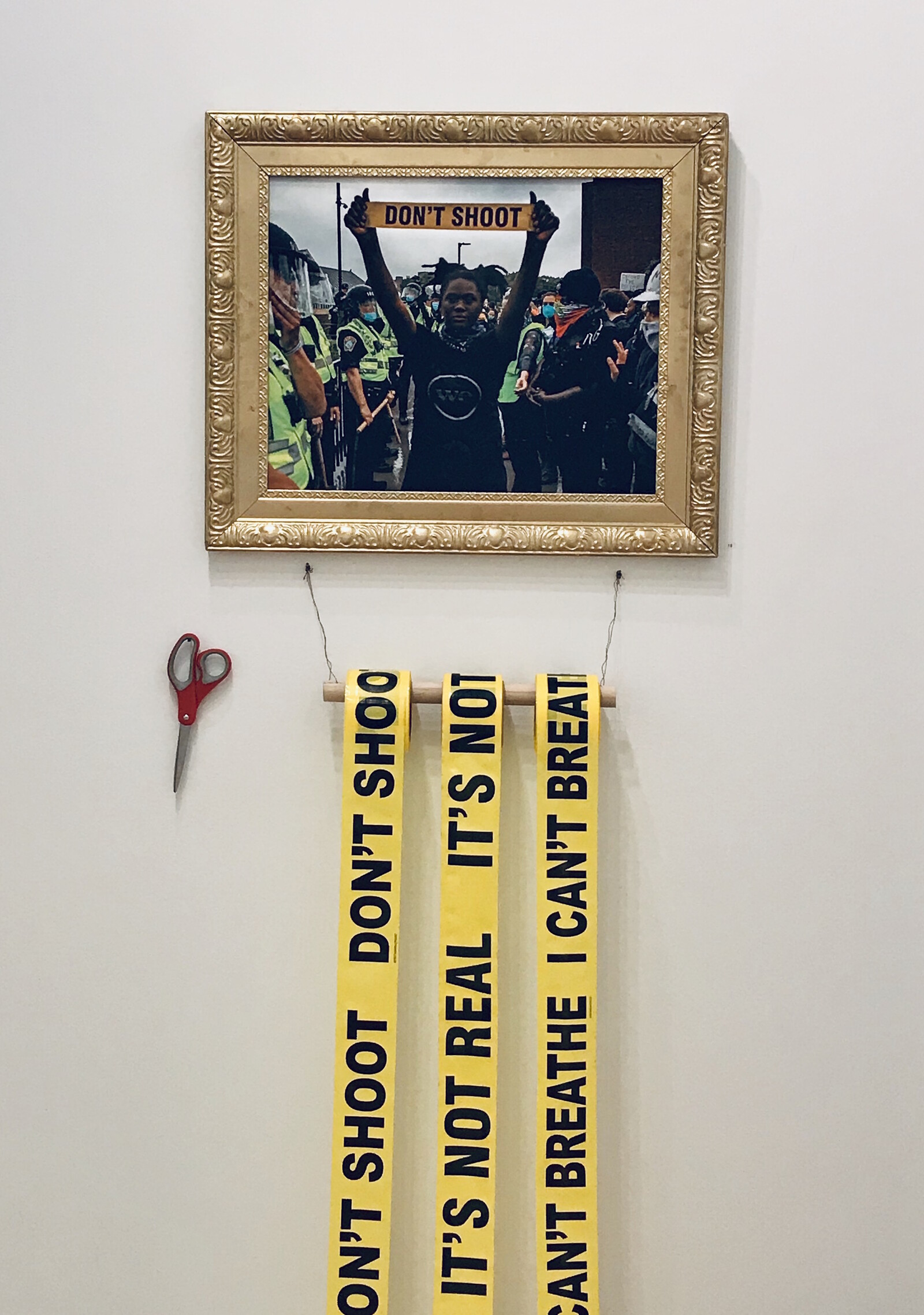

The group show “I Am My Best Work” at the Painting Center in Chelsea makes a more pointed response to contemporary politics. Inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement, the exhibition—curated by Shazzi Thomas and Perri Neri—sets out to amplify the voices of 15 Black, Indigenous, and People of Color artists, while also examining the present climate of social unrest and mass demonstrations. Cedric “Vise1” Douglas, a designer and street artist, presents two works that simultaneously act as instruments for demonstrations: a series of tambourines or noisemakers with painted black-and-white portraits of the nine victims in the Charleston shooting massacre, and a photograph of a protestor holding caution tape that reads “DON’T SHOOT.” Hanging below the photograph is a dowel with three separate rolls of caution tape (“DON’T SHOOT,” “IT’S NOT REAL,” and “I CAN’T BREATHE”) and a pair of scissors, there for viewers to cut off a ribbon of tape to use at future protests.

At Bridget Donahue in Chinatown, Lisa Alvarado presents a body of work that looks back at the deportation from America of roughly two million people of Mexican descent during the Mexican Repatriation of 1929 to ’36. The exhibition, titled “Thalweg”—the line of lowest elevation within a valley or watercourse that defines the border between two states—features sound installations, sand textures, family photographs, and large free-hanging paintings, incorporating lace, burlap, and wood, that conceive the border, space, and memory as fluid abstractions. The works render changing topographies, real and imagined, and fluvial shapes and designs. Much like Whitten’s work, Alvarado’s paintings (or assemblages) explore a cosmic sense of memory and place, with an added emphasis on sound and movement.

Alvarado’s work calls attention to the idea of mestizaje, which refers to the cultural and ethnic mixing in Mexican history, and is here expanded to mean a mixing of ideas and materials as a way to resist or bridge cultural and conceptual divides. At Petzel’s newly expanded Upper East Side gallery, Rodney McMillian continues his investigation into the link between American landscape painting and abstraction. Here, the artist uses as his canvas crocheted blankets made of colorful yarn. Heavy layers of latex paint sit on the surface, absorbing threads of yarn into stiff, dry pastes of muted colors, at times resembling an off-color American flag. Its stars morph into diseased blobs, plagued by a growing sickness: racism. Like many of the works I viewed, these breathtaking pieces become objects to encounter with the body. The viewer moves around them, finding solace in the experience of looking, but also in the act of resistance to accepted truths.