The logic of contagion rests on an “us vs them” binary—healthy/sick, in/out, loved/feared—and this exhibition of nine mostly UK-based Latin American artists has the feeling of a diverse group banding together for support. Instigated and curated by the Venezuelan painter Jaime Gili, it foregrounds the importance of collegiality and self-organization in an increasingly hostile environment.

The show tackles pressing political questions with a looseness and lightness of touch characterized by subtle metaphors rather than on-the-nose statements (the exception is a billboard-sized map at the entrance to the gallery, which shows the proliferation of legal and illegal mines across the Amazon basin). In Martín Cordiano’s Host (2020), a tall reading lamp pierces through a mid-century sideboard, on one corner of which a massive sphere of plaster bulges like a tumor. The result is witty, oddly beautiful, and violent. The exhibition text identifies Jacques Derrida’s writing on hospitality as an influence on Cordiano, who seems here to be giving form to the anxieties generated by the a guest’s fragile relationship to their host: a figure who ostensibly extends care while constantly policing the boundaries of the offer of hospitality.

Resting on a nearby plinth is an oversized bronze cast of a breadcrumb. The 2012 work by Manuela Ribadeneira, titled Partícula de dios (o una miga de pan) [God Particle (or a breadcrumb)], was inspired by a ridiculous—or sublime, depending on one’s spiritual inclinations—true story. In late 2009, while scientists at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN were attempting to prove the existence of the Higgs boson (the “God particle”), a bird believed to be a pigeon dropped a piece of a baguette on a part of the accelerator, causing it to overheat. Birds and bread are biblical symbols, and there is something both amusing and numinous about these religious motifs conspiring to halt the efforts of science.

In his own work in the exhibition, Gili wrestles with the limitations of geometric abstraction as a means of representing political concerns. The bright colors of a528 (Republic Announcement) (2019)—painted in response to Juan Guaidó’s bid to oust President Nicolás Maduro and end the crisis engulfing Venezuela—convey a glimmer of hope for a better future. But its neon, sugary hues betray a sense of inflated and manufactured promise, which the painting’s rough edges and blotchy patches substantiate. Alexandre Canonico’s But (2020), an irreverent painting-cum-sculpture, trades in similar bright colors, though the emphasis is on the formal interplay of disparate materials. The work comprises a rectangular plank of plywood spray-painted red, with movable parts fitted into curved paths carved into its surface: yellow wheels and a blue plug which fits on the top, like a silly hat. Sitting somewhere between a wood puzzle and a pop painting, it’s a playful, cartoonish work.

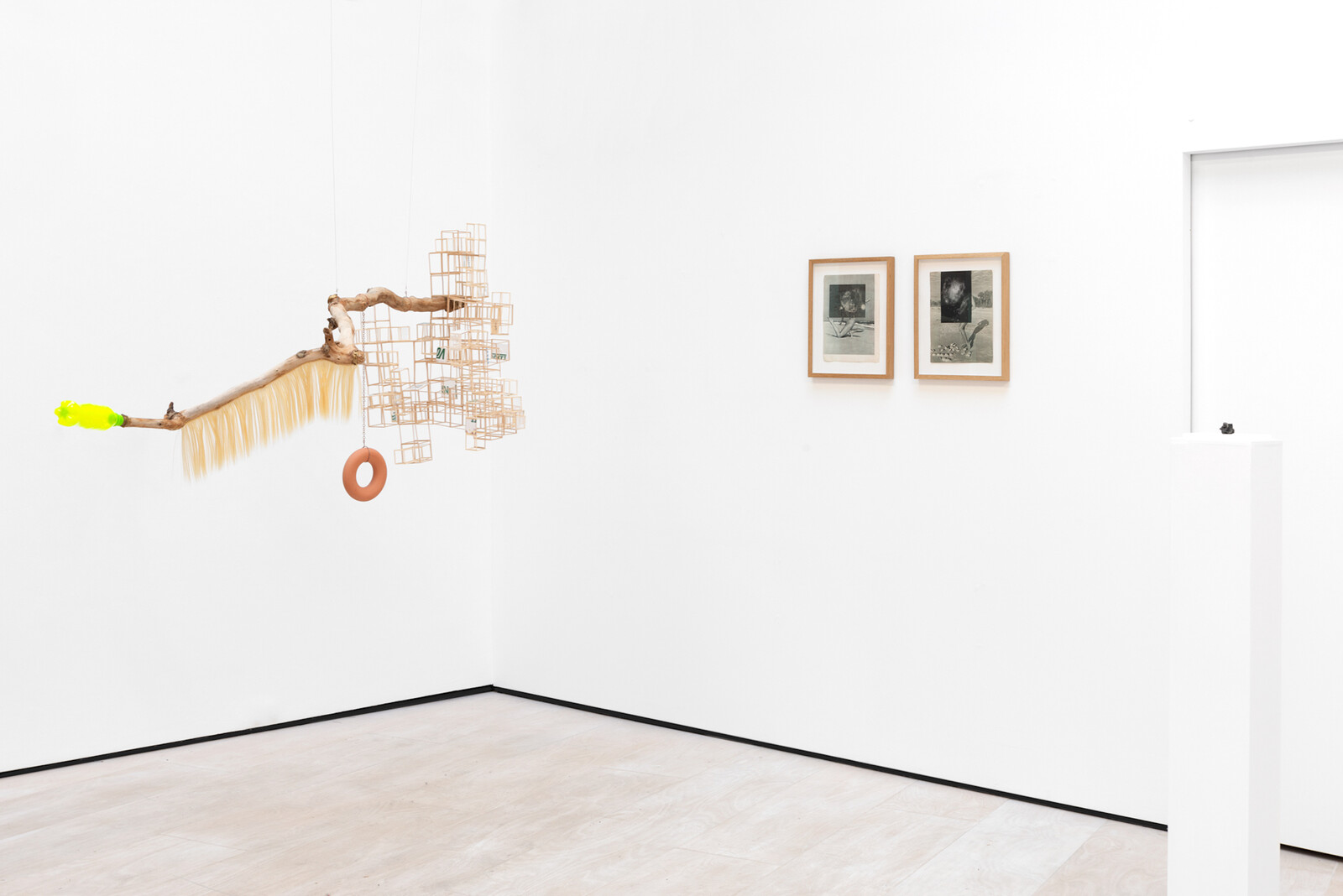

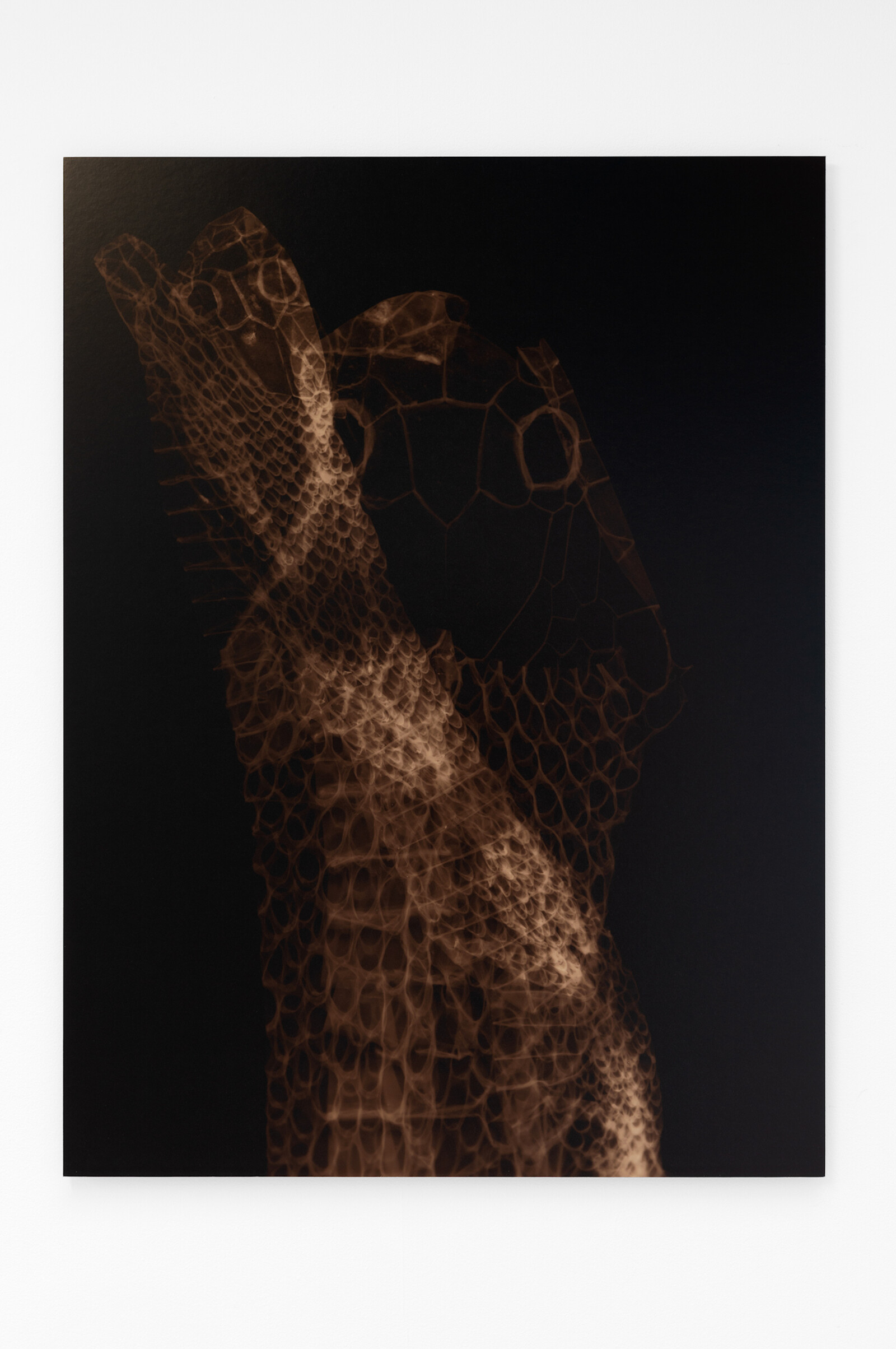

But in the world of this small, artist-led exhibition, the ludic and the gruesome sit side-by-side; an open-ended approach that allows free associations to emerge naturally between the heterogenous works. Lucía Pizzani’s Todopoderosa (2019)—a digital enlargement of a brown-hued photogram made with (ecologically sourced) translucent snakeskins—references the Aztec rituals in honor of Xipe Totec (or Flayed Lord), a god of fertility and regeneration, during which priests flayed sacrificial human victims and wore their skins.

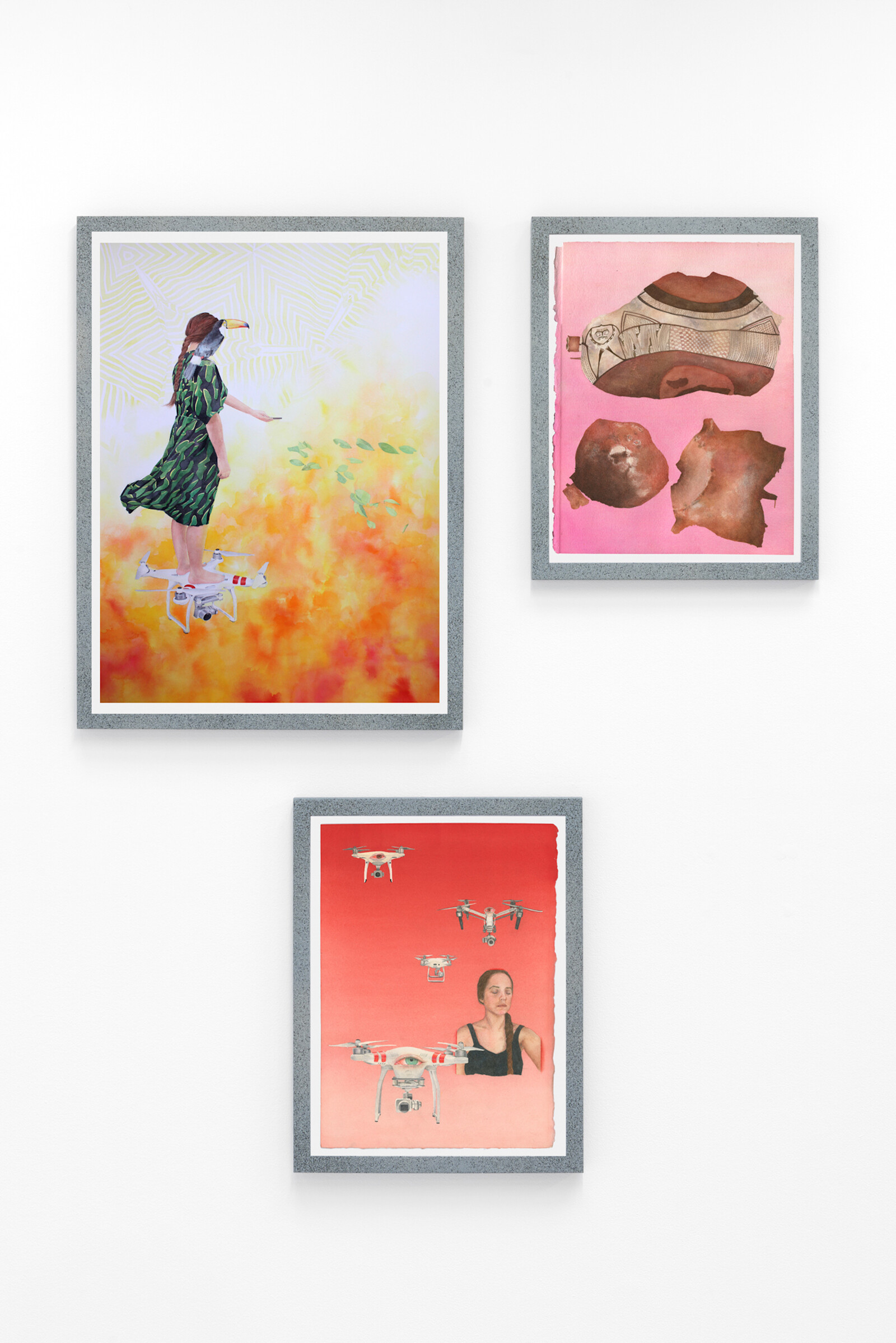

On the same wall, Patricia Domínguez’s watercolors explore the troubled relationships between humans, animals, and the natural world. In Monsters of Levitation, a young woman with a toucan on her shoulder floats mid-air on a drone as she tends to vegetation against a flame-red background, while in Shapeshifting Lines (both works 2019) she is surrounded by flying drones which each have a single human eye, like uncanny cyclopses. The surreal images, which stem from Domínguez’s experiences caring for animals blinded by fires in the Bolivian Amazon, also allude to the anti-government protesters who have in recent months been blinded by tear gas canisters in her native Chile. As these works’ combination of dreamlike imagery and pressing contemporary issues suggests, “Contagio” presents a cacophony of voices, ideas, and styles, foregrounding artistic association rather than a cogent curatorial theme. While this may frustrate those seeking a neatly packaged picture of contemporary Latin American art, it delivers something messier and ultimately more alive.