Delicate sheets of paper are scattered over the floor of Jala Wahid’s exhibition at Niru Ratnam Gallery. The pieces are reminiscent of leftover protest flyers and posters, giving the sense that a demonstration has taken place. The Kurdish-British artist’s exhibition continues her interest in exploring materiality, investigating the symbolic elements of archival objects. Wahid’s latest series of works is heavily informed by her research at the Kurdish Cultural Centre and the UK National Archive in London. The two archives focus on contrasting aspects of Kurdish history, with the former dedicated to the lived experiences of the Kurdish community, and the latter serving as a public record, listing details of treaties, conflicts, and political policies.

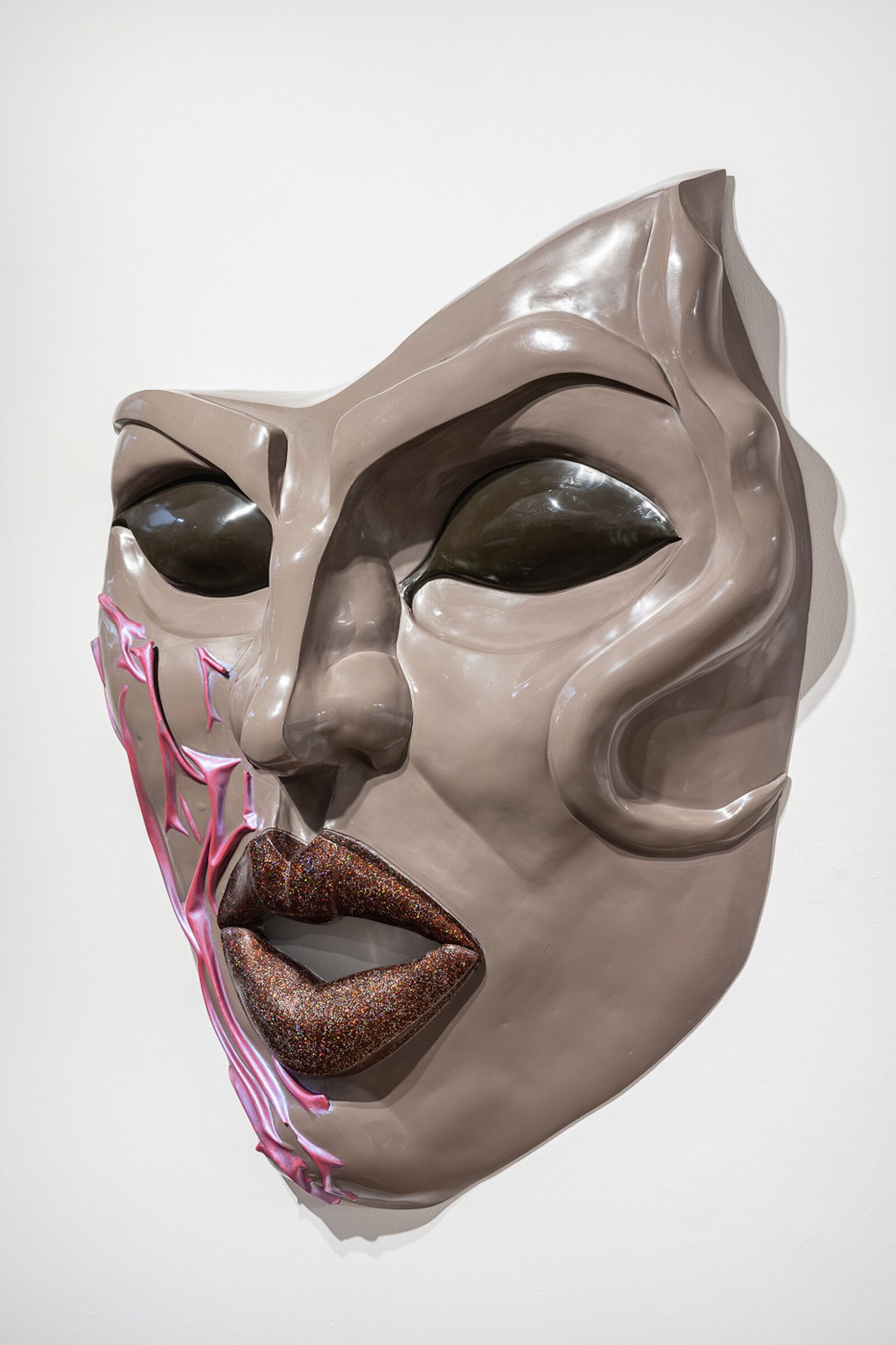

“Aftermath” is a collection of seven compelling objects and texts, with two sculptures hung on the wall, two sculptures placed on a long base, two text pieces displayed on plinths, and the paper cut-outs spread across the gallery floor. The exhibition prompts questions including: Who is allowed to narrate history? How does one document that history? And, most importantly, how are cultural identities formed? As with much of Wahid’s work, these recent pieces embody a sense of memory. The artist captures moments of conflict and celebration, questioning forgotten histories by preserving the past. Her resin and fiberglass sculptures celebrate the untold histories of Kurdish culture by focusing on women. Glossy surfaces are accented with expressive color, oozing glamor as Wahid depicts fragmented representations of women, their eyes closed and their lips painted with shimmering lip gloss. In Inflammatory, Revolutionary Fever (2021), a smooth-textured green-skinned woman reclines, tendrils of her hair dipped in gold glitter.

Alluring and sensual, these works exist outside of the controlled narratives surrounding Kurdish culture, paying homage to Kurdish music and offering an image of Wahid’s heritage that sidesteps representations of tragedy and war in favor of a more nuanced link between the cultural and the political. Wahid’s glazed sculptures are juxtaposed with archival texts that narrate the history of Kurdistan through the lens of western society using excerpts of correspondence taken from the National Archive. The Profitless Gift (2021) reimagines archival texts, weaving together excerpts and quotes to form a play that follows the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and discusses Britain’s attitude regarding Kurdistan. Narrated by government officials, the Kurdish ethnic group are referred to as “primitive,” with one official describing “The Kurd” as having “the mind of a school boy.” Through texts from the public archive, the viewer observes how power is exercised, returning to the role that such narratives play in shaping international politics and cultural identity.

By displaying these excerpts in the gallery space, Wahid decontextualizes past narratives, contemplating notions of collective memory and cultural erasure. In his essay “An Archival Impulse,” Hal Foster describes the nature of archives as “found yet constructed, factual yet fictive, public yet private.”1 Wahid explores the topology of two existing archives, observing how they work in tandem to paint a picture of the complex documentation of Kurdish culture. These two archives are a catalyst for a conversation that tiptoes between the poetic and the political: while Wahid’s sculptures are influenced by the poetics of the materials she found in the Kurdish Cultural Centre, her texts are anchored in the political narratives of the National Archive. Large-scale sculptural works such as Nothing but Small Wars (2021) and Let Me Breathe You In Before They All Do, Tastes Like Everybody’s Fighting For You (2021) are singular, tactile objects that depict acrylic nails and an expressive portrait of a woman’s face, eyes closed, mouth open, mirroring the fragmentation of archival materials.

Dizzying and disjointed, Wahid’s sculptures and texts evoke contemplation around historical bias, specifically the history of minority ethnic groups. Progressing through the exhibition, the viewer is presented with fragments from a community with a long and complicated history, observing the connection, or lack thereof, that these artworks have to one another, and the transformative potential of revisiting memories and historic events through a contemporary lens. What type of exchange takes place when two archives are placed in dialogue with one another? By examining the interrelationships between the archives and stories Wahid focuses on, one can begin to understand both how they coalesce to tell a story of the past, and how they influence cultural identity in the present. Although the archival texts narrate tales of violence and suffering, the artist revels in the beauty of her diasporic community. Her sculptures capture the nuances of Kurdish culture, demonstrating that marginalized communities are not defined by their collective trauma.

Hal Foster, “An Archival Impulse,” October, vol. 110 (Fall 2004), 5.