Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

November 15, 2024 – Review

62nd New York Film Festival, “Currents”

Almudena Escobar López

Days before the New York Film Festival opened, dozens of filmmakers—many from the “Currents” section—published a petition urging the festival to cut ties with Bloomberg Philanthropies due to concerns over its implication “in facilitating settlement infrastructure in the West Bank and denying Palestinians their basic rights.” During the fortnight, anti-war demonstrators interrupted Q&As and screenings, and a parallel Counter Film Festival was organized. How do we approach film-making after a year of live-streamed genocide in Gaza? This question lingered over the “Currents” shorts programs, curated by Aily Nash and Tyler Wilson, which seek to foreground “new and innovative forms and voices.” A select group of films from the programs challenged how images influence our perception of reality, particularly in contexts of violence, prompting critical reflection on our roles as viewers.

Two films in “The Will to Change” program reveal the limits of observation, turning the horror of witnessing war into an act of self-reflection. Black Glass (2024) by Adam Piron conjures the ghosts of the past (and the present) by speaking about the intrinsic relationship between early image-making technologies and the ongoing processes of settler colonialism. Piron examines Eadweard Muybridge’s early photographic work, commissioned by the US Army to capture …

September 25, 2024 – Review

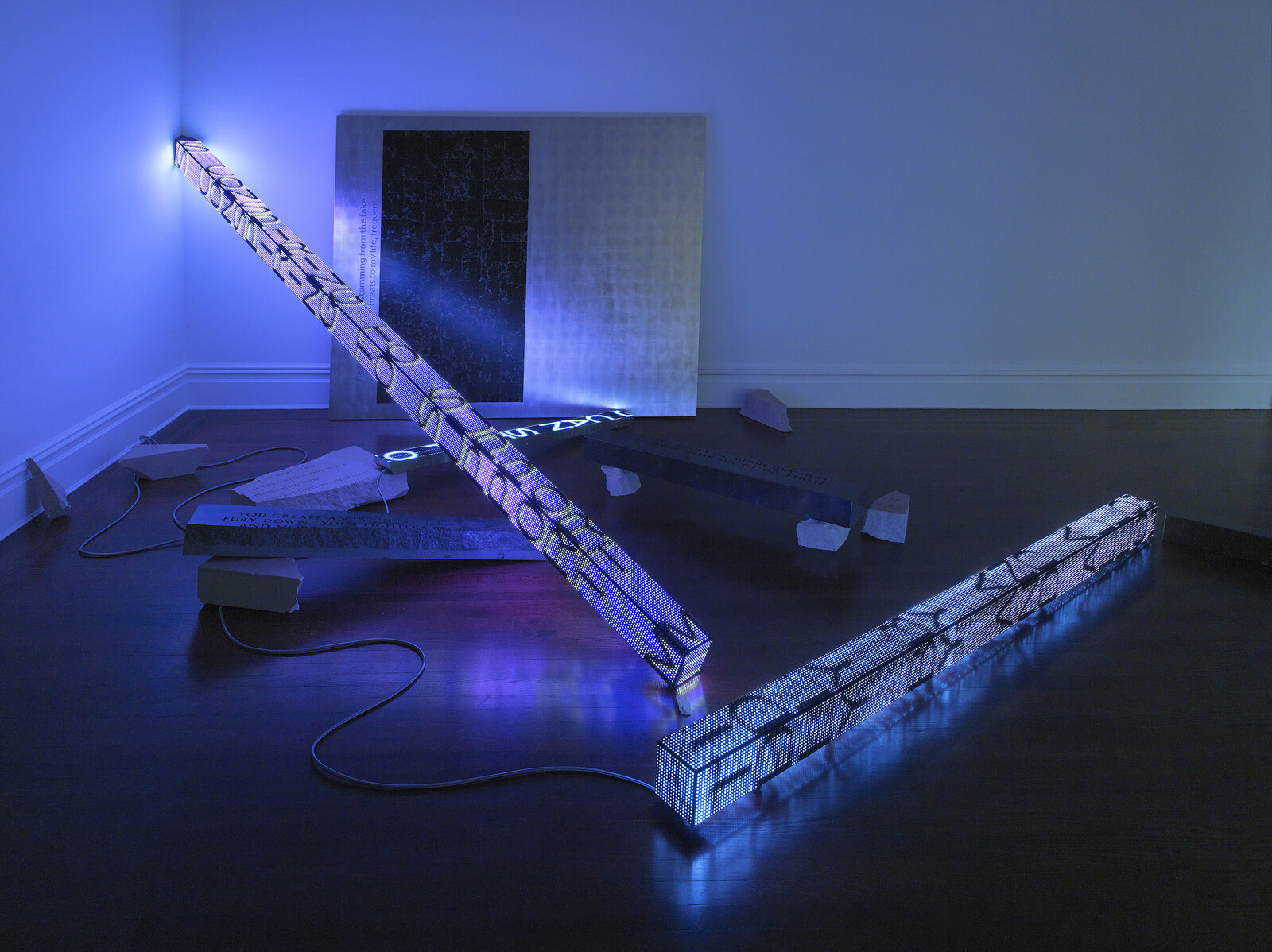

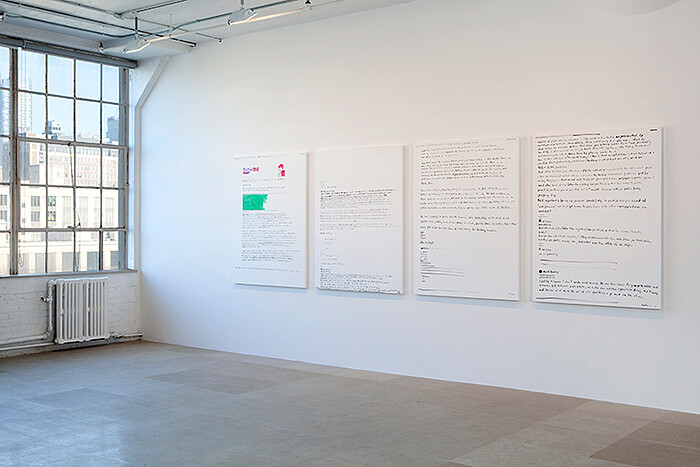

Jenny Holzer’s “WORDS”

R.H. Lossin

Jenny Holzer began making her ongoing series of “Truisms” in 1977. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, truism indicates “a self-evident truth, esp. one of minor importance; a statement so obviously true as not to require or deserve discussion. Also: a proposition that states nothing beyond what is implied in any of its terms.” The word “truism” means more or less the same thing as “platitude” or “cliché”—unremarkable, banal observations—but the fact of its orthography nudges it, just slightly, toward a charged moral terrain of reality and deception.

Today the word’s appearance, unlike its synonyms, reminds us how contentious such a notion of obvious and easy truth has become. The same statement is either widely repeated nonsense or unquestionable fact depending on who you ask. This has always been the point of Holzer’s text-based works. “Truism” underscores the tension produced by common sense and capital T truth that animates her scrolling digital billboards, engraved park benches, projections, and painting of redacted documents.

Making strange claims in the form of a brief declarative statement or maxim draws attention to the ways that sense becomes common (or doesn’t) and underscores how difficult, if not impossible, it is to produce …

September 20, 2024 – Feature

New York City Roundup

Orit Gat

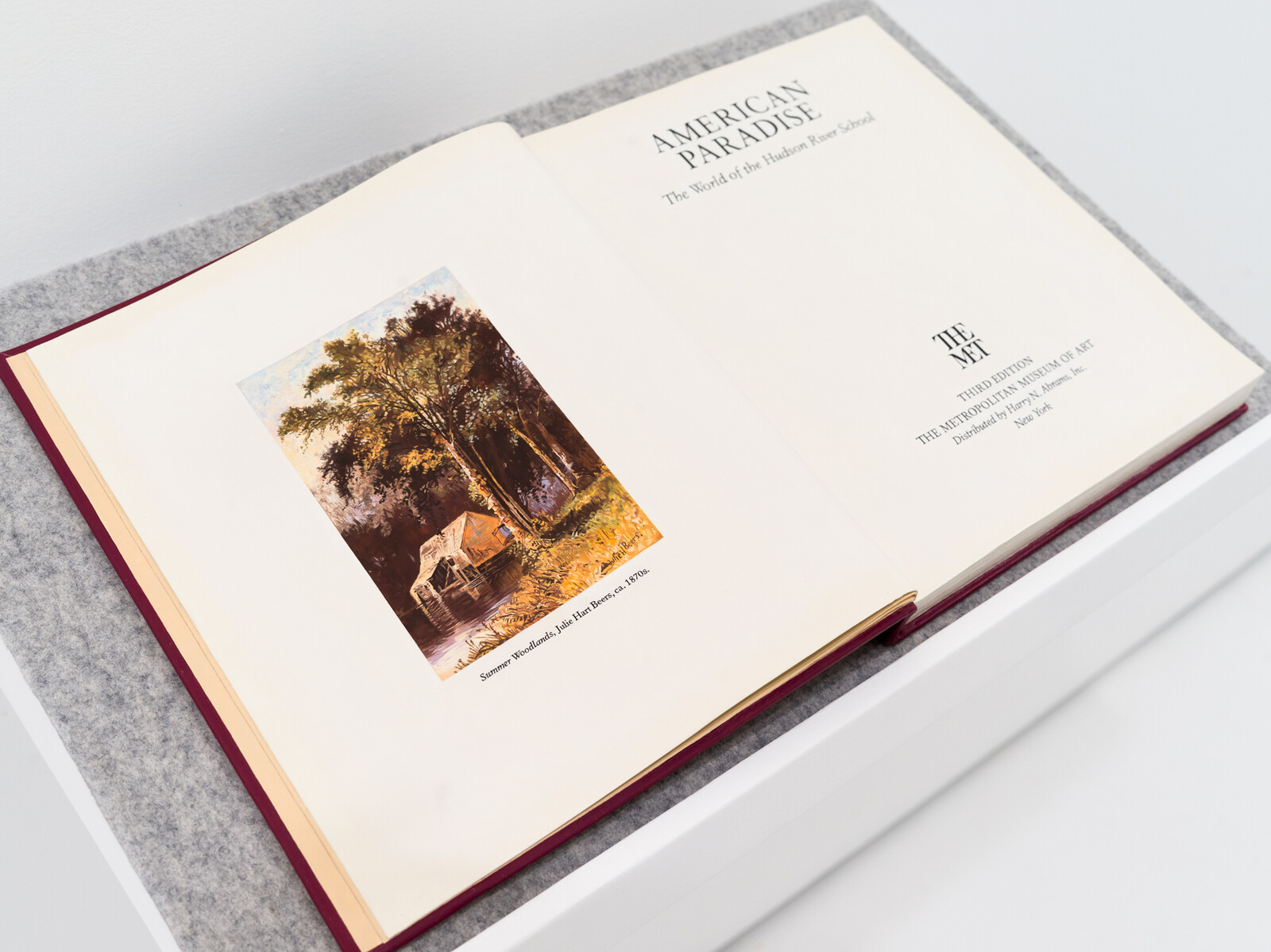

“American Paradise”: Anna Plesset took the title of her show at Jack Barrett Gallery from a 1987 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art about the nineteenth-century Hudson River School of American landscape painting, which featured twenty-five male artists and not a single woman. Plesset responds by researching the work of women artists of the time, applying an astonishingly skillful trompe l’oeil technique to the task of filling in historical gaps.

Her show opens with a sculpture mimicking the original exhibition’s catalogue, a perfect facsimile in oil on epoxy, aluminum, and steel placed on a plinth. Ostensibly the catalogue’s third edition (only one edition was published), the frontispiece is here replaced with a painting by a woman artist, Julie Hart Beers. In Value Study 2: Niagara Falls / Copied from a picture by Minot / 1818 (2021), Plesset paints an impeccable reproduction of the paper printout of an online image search for Louisa Davis Minot’s painting of the waterfalls, as if adhered to the canvas for reference using blue painter’s tape. The canvas itself shows the sketch and a beginning of a copy of Minot’s original. Plesset’s realism is not a remedy for historical injustice but a conceptual stop-and-start, a …

September 18, 2024 – Review

Whitney Biennial Performance Program

Sanna Almajedi

Taja Cheek—currently artistic director at Performance Space New York, and an artist in her own right as L’Rain—has long advocated for the inclusion of sound artists and musicians in the gallery space, as central figures rather than an entertainment vehicle to lure crowds. This year’s Whitney Biennial featured a five-part performance program, curated by Cheek, featuring an array of performances deeply rooted in sound. Artists Debit, Sarah Hennies, Holland Andrews, Alex Tatarsky, and JJJJJerome Ellis presented electronic music, improvised sounds, an experimental music ensemble, and a sonic exploration of language.

The program began with Debit, playing music from her album The Long Count (2022), which imagines the music of the Mayan civilization through a theatrical and fantastical three-act performance, using intense drone sounds and samples of precious and eerie wind instrumentation. The stage consisted of a mountain made out of a pile of dirt/wood, spot lights and a curtain that was lifted at the end of the show to unveil the Whitney’s majestic view of the Hudson River, alluding perhaps to a call for the land. Debit used synthesizers which, according to the press release, “have sampled and processed the sounds of Late Postclassic Maya wind instruments. Using tones from …

September 6, 2024 – Review

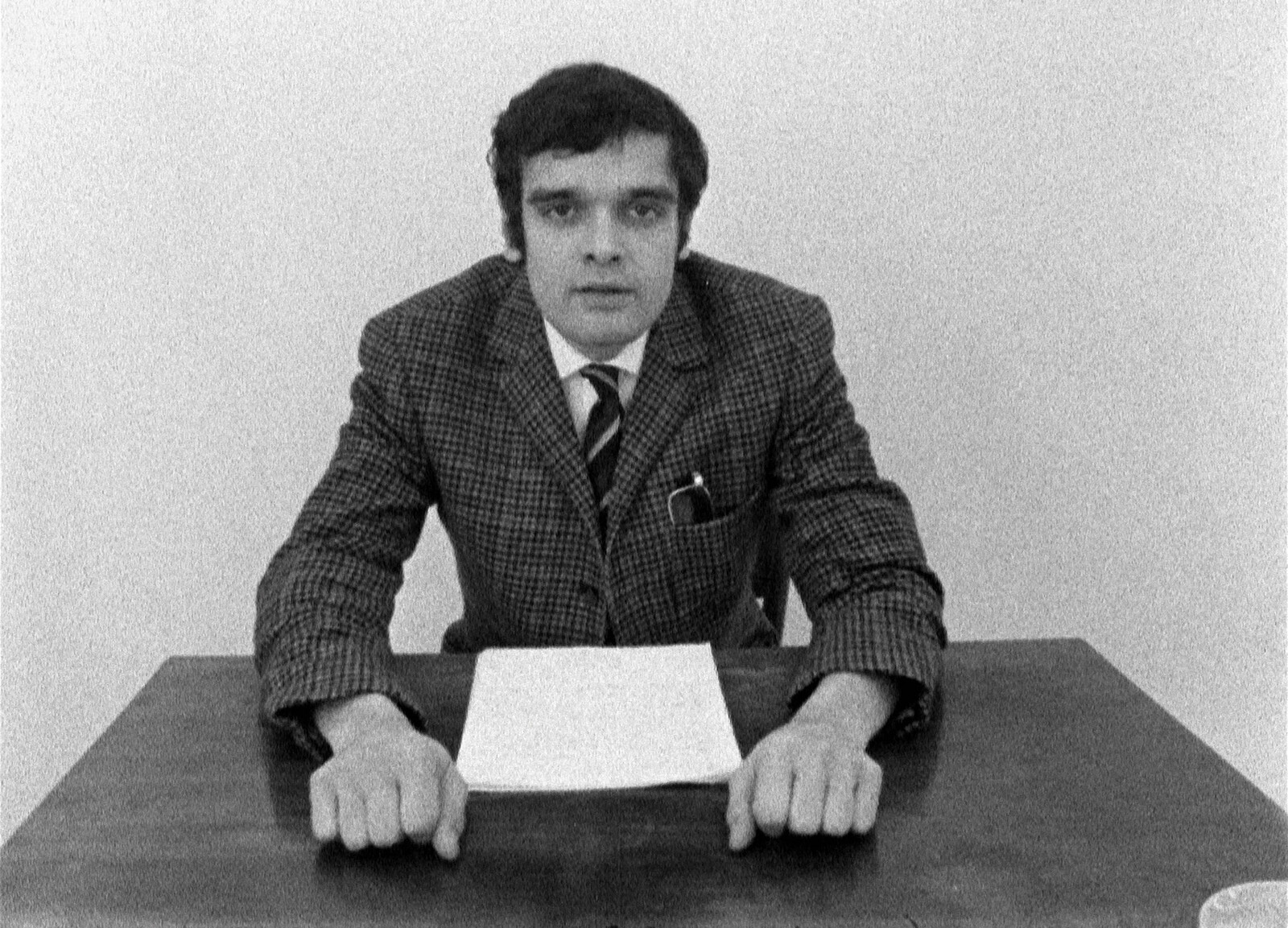

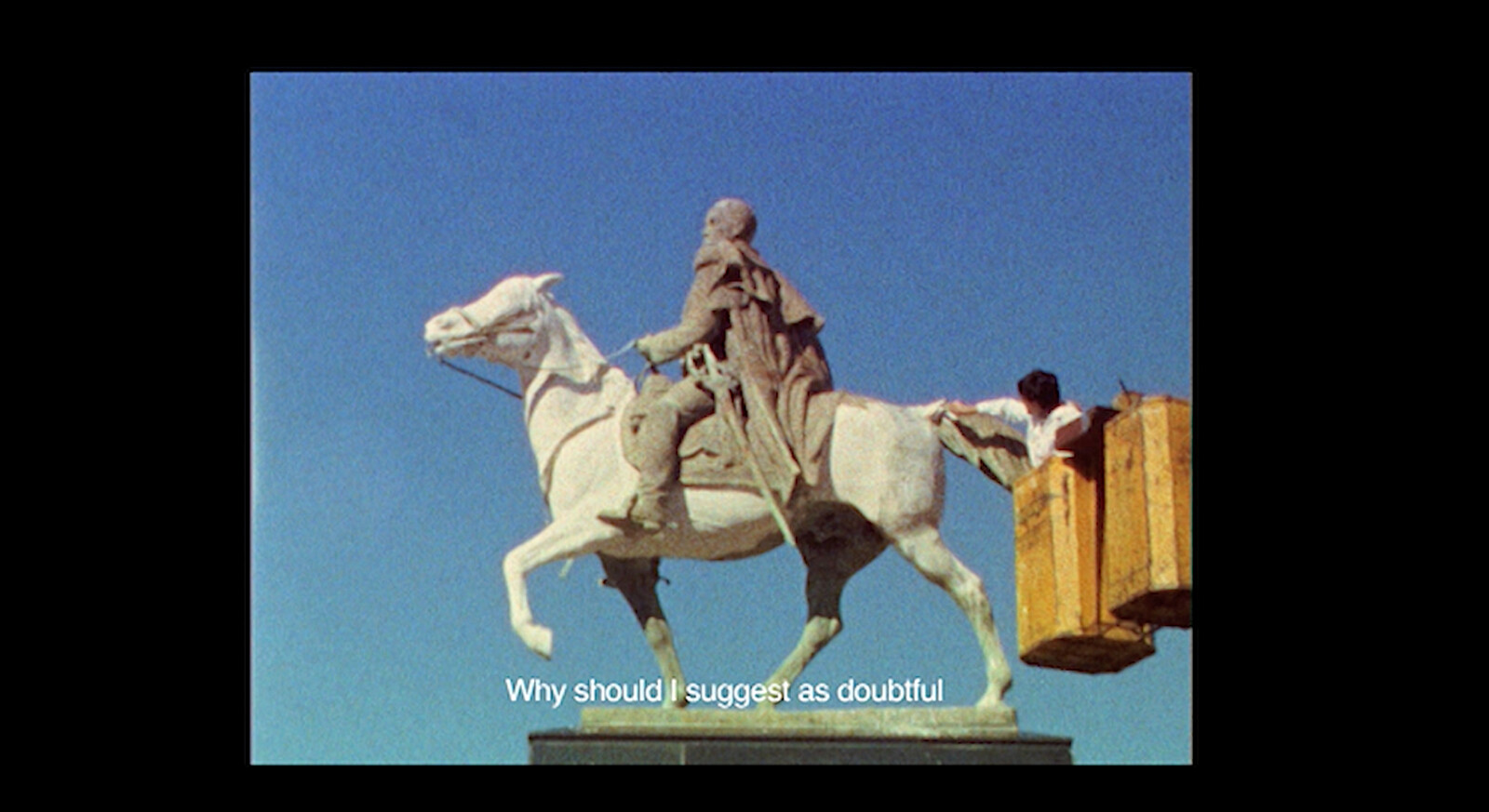

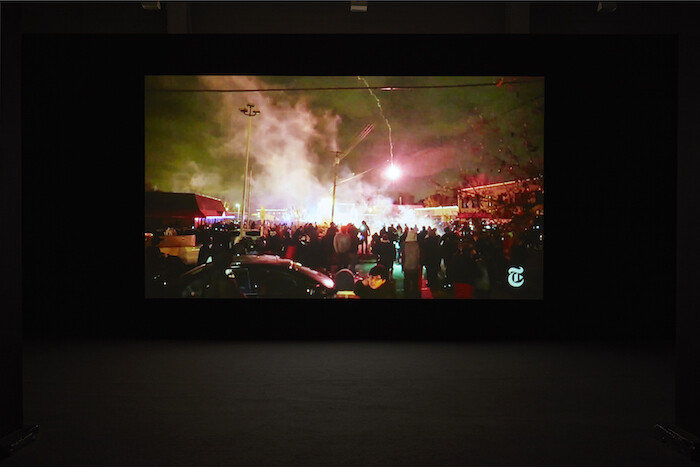

Harun Farocki’s “Inextinguishable Fire”

Leo Goldsmith

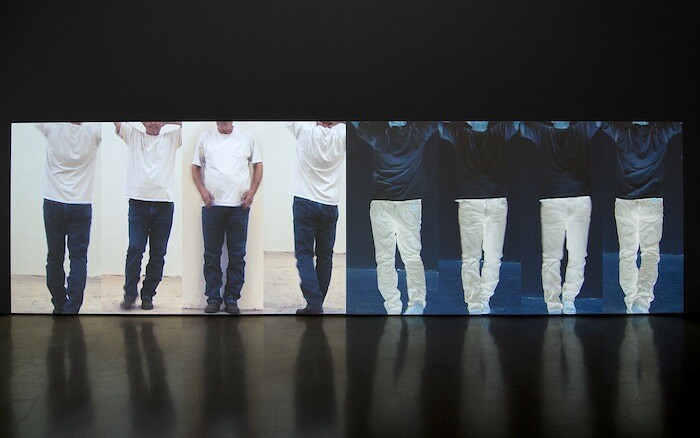

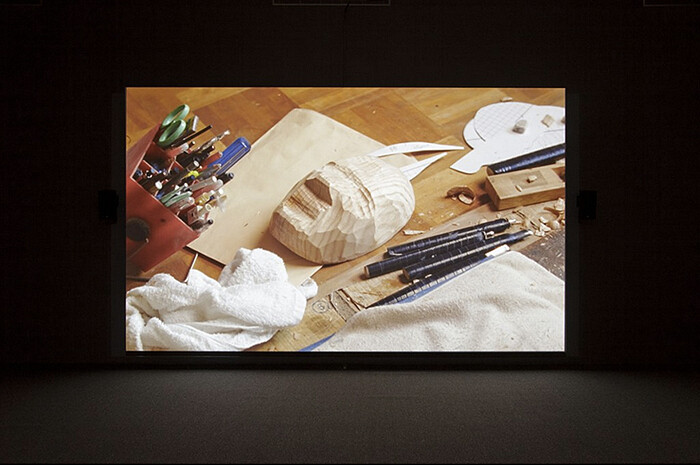

Greene Naftali’s new exhibition of works by Harun Farocki derives its title from perhaps the German filmmaker’s most famous work, a gently excoriating and laser-sharp 1969 film about the complicity shared amongst politicians, Dow Chemical executives, and ordinary workers in the production of the chemical weapon napalm. Inextinguishable Fire remains utterly devastating, a frightening but cogent delineation of the phases of dissociation we experience as we gaze at media images of atrocity, and a methodical examination of how the abstraction of labor makes us unconscious of our complicity in the violence of war.

Here, however, the specificity of Farocki’s title is, along with its definite article, lost. This lends it a more nebulous quality. Perhaps the “inextinguishable fire” in question refers not to a chemical weapon, the slightest drop of which—the film’s voiceover narration tells us—burns for half an hour at a temperature of 3,000 degrees Celsius. In the context of a show that marks a decade since the filmmaker’s death, the title almost sounds like a tone-deaf tribute to Farocki’s burning legacy. It loses its precision as a catch-all for a group of works that branches two different phases of the filmmaker’s career (the 1960s and the 2000s) and …

June 18, 2024 – Review

Tolia Astakhishvili’s “between father and mother”

Chris Murtha

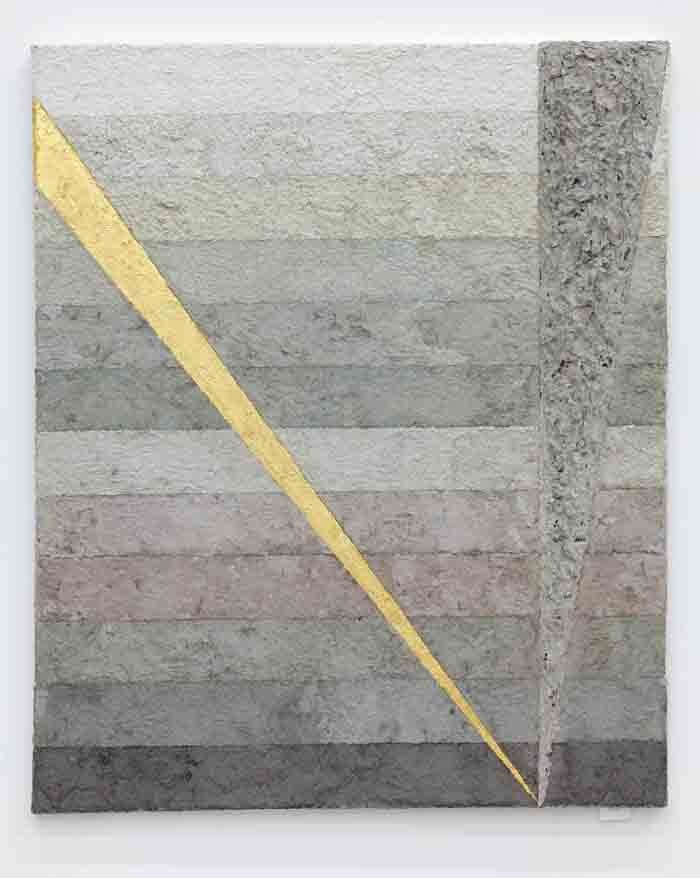

Built from conventional architectural materials including drywall and cement, and later stained with coffee, dirt, and pigment to mimic the wear and tear of time, Tolia Astakhishvili’s installations hover between construction and destruction. SculptureCenter’s brick and cast-iron building, initially designed for repairing trolleys and later used to manufacture derricks, hoists, and cranes, proves a fitting host for the Georgian artist’s first exhibition in the United States. Having previously explored the mutability of domestic spaces, and how they accumulate the marks and alterations of their inhabitants, Astakhishvili here contends with a formerly industrial site, while still remaining focused on what spaces tell us about humans come and gone.

As she did with two recent exhibitions in Germany, Astakhishvili incorporates collaborative projects and works by peers into her installation—an extension of, rather than challenge to, authorship. A microcosm of the exhibiting institution, her fabricated environments become fleeting hosts for her own and others’ artworks. The first sculpture visitors encounter is Astakhishvili’s The endless House (all works 2024 unless otherwise stated), a freestanding cement and particleboard wall modeled on those found in the building’s basement. The structure’s narrow cavities harbor a sculpture and photograph by Katinka Bock and reverberate with the sound of …

June 12, 2024 – Review

Fernando Palma Rodríguez’s “Āmantēcayōtl”

Xenia Benivolski

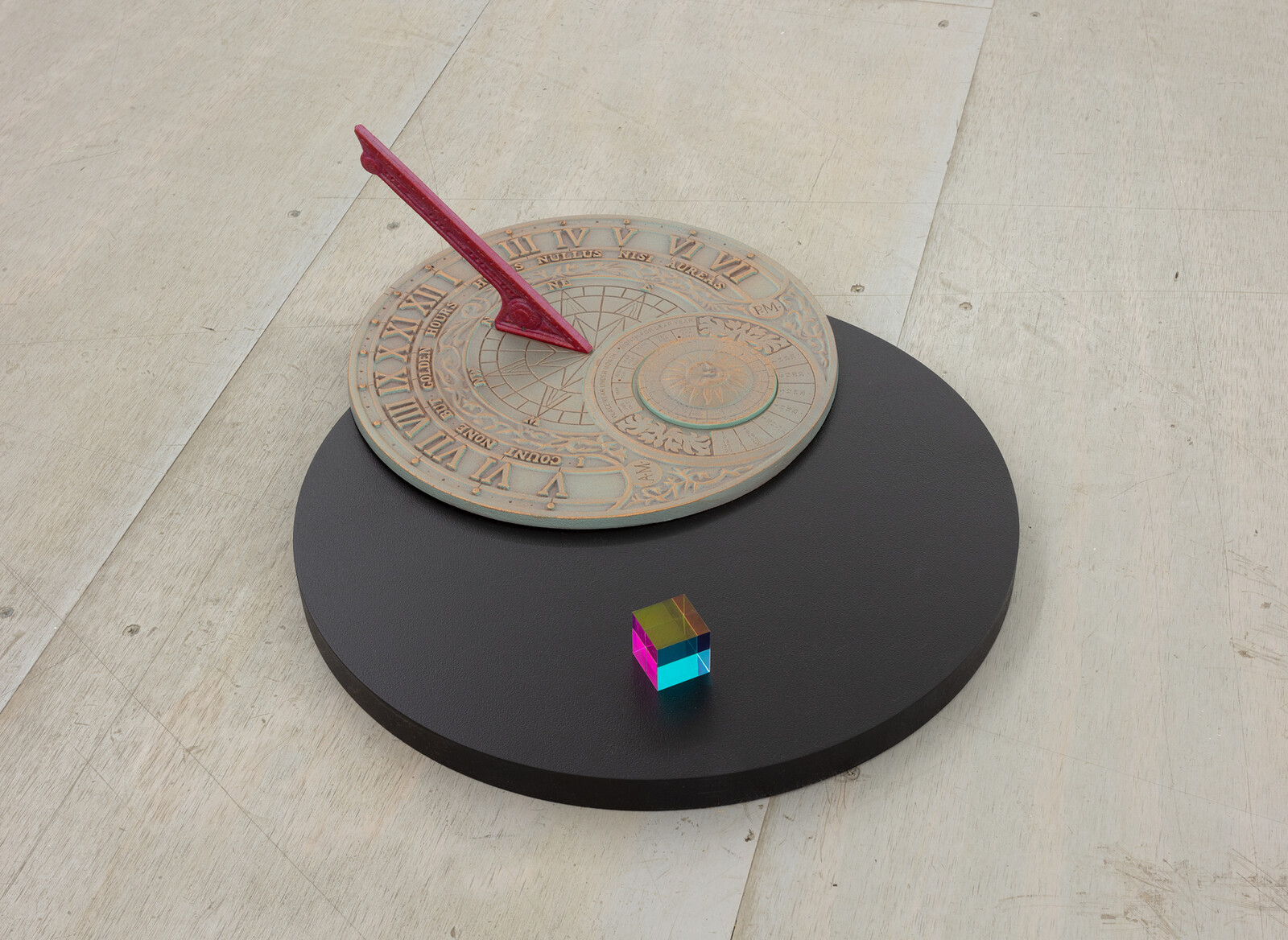

When I first visited the wall between Mexico and the US in Patagonia, Arizona, in 2017, the town was celebrating: the redevelopment of a large patch of agricultural land had been halted due to the discovery of traces left by a jaguar. In one dramatic appearance, the endangered animal had accomplished what land activists had been trying to do for years. In this same spirit, Fernando Palma Rodríguez’s work plays on the symbiotic relationship between nature and technology, hinting at the possibility of alliance between animals, machines, and humans in the interest of anti-capitalist resistance. Rodríguez is an artist trained as a mechanical engineer whose 1994 robotic installation, Greetings, Zapata Moles—sewing machines adorned with traditional Mexican wrestling masks—responded to the industrialization of his hometown. Rodríguez’s latest robotic work likewise anthropomorphizes technological objects while extending the definition of technology to include unspoken, embodied forms of knowledge that sustain the living practices of Mesoamerican cultures, with particular reference to the Nahua cosmology.

At Canal Projects, Rodríguez draws parallels between the energetic currents that power physical, electronic, and metaphysical grids, and the cosmogenic principles that tie humans to the earth. “Āmantēcayōtl: And When it Disappears, it is Said, the Moon has Died” tells …

May 23, 2024 – Review

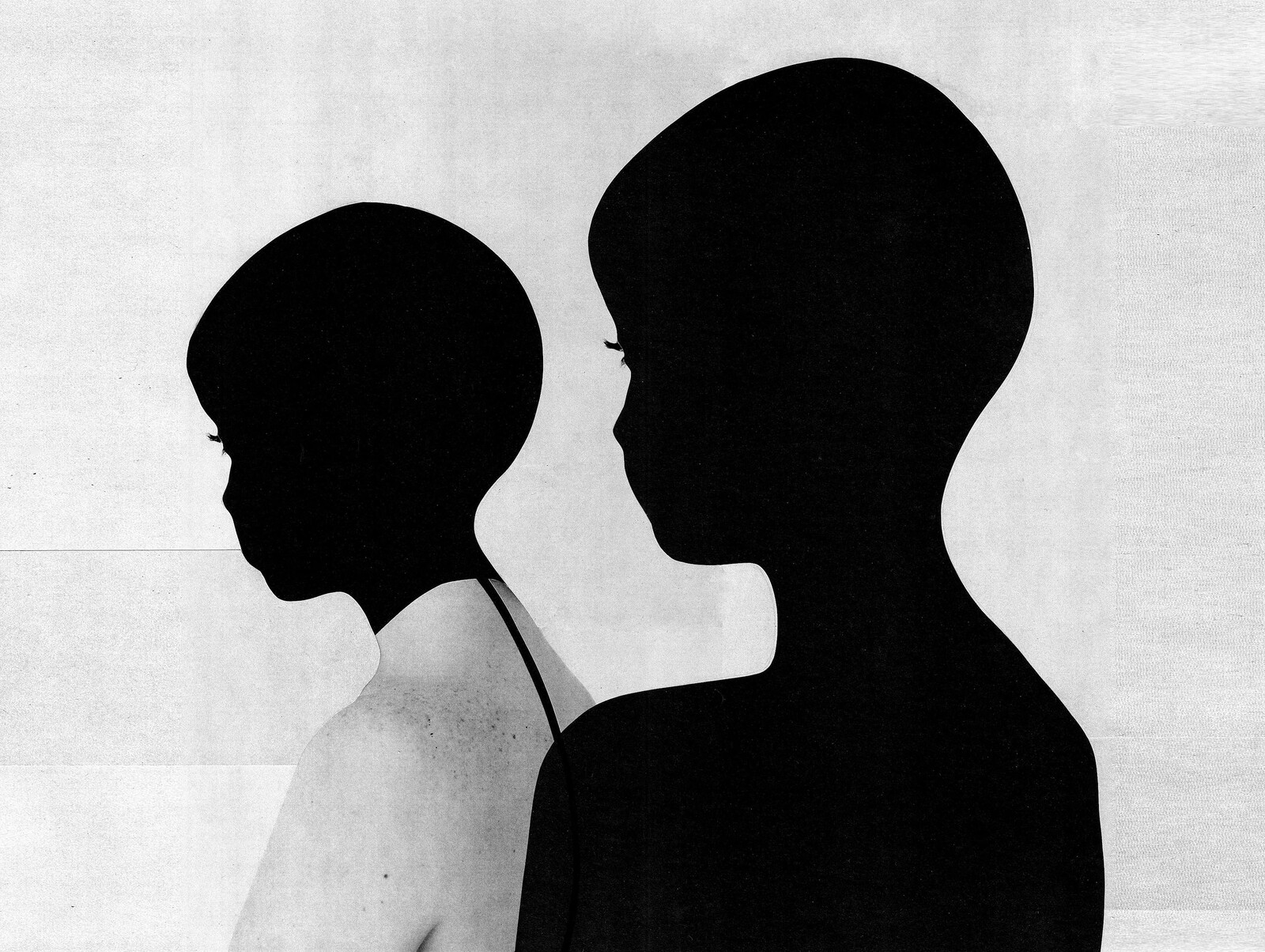

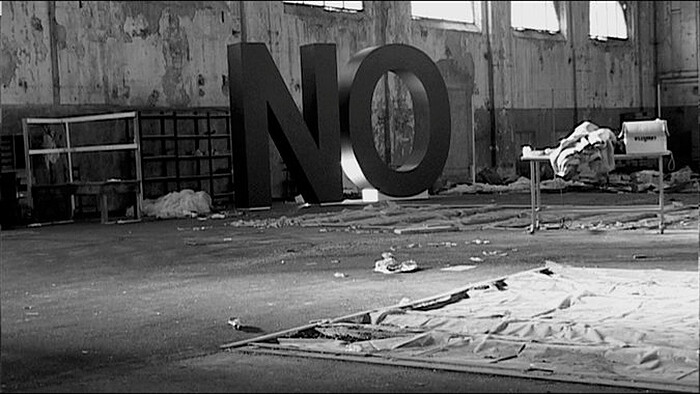

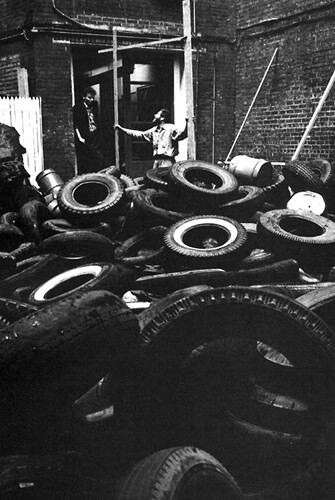

Arthur Jafa’s “BLACK POWER TOOL AND DIE TRYNIG”

Travis Diehl

With the subtlety of a revolver, Arthur Jafa’s merciless ***** distilled the racial psychopathy of Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) by replacing the white characters in its climactic bloodbath with Black ones. Robert De Niro and Jodie Foster still play Vietnam vet Travis Bickle and the pubescent sex worker he thinks he’s saving but—by recording new performances and stitching them into the original footage—Jafa transformed the white pimp Sport into the Black Scar, the bouncer and the john were made Black, and so too the horrified cops who edge in after Bickle has emptied his guns. This wasn’t so much a subversion as a restoration: the script had called for a Black body count, but was recast to avoid inflaming audiences. Critics of Jafa’s redux—recently screened at Gladstone Gallery—have complained that Taxi Driver was already about race. But Jafa’s grim snuff film takes that fact to be obvious, then warps it, repeating his revised climax with small differences and new surprises, for seventy-three minutes.

Jafa’s show of sculptures at 52 Walker carries the same themes of Blackness, erasure, violence, and moving images, but in a more damning, paranoid register. A walkthrough structure, studded with extruded aluminum sculptures like bisected window …

May 17, 2024 – Review

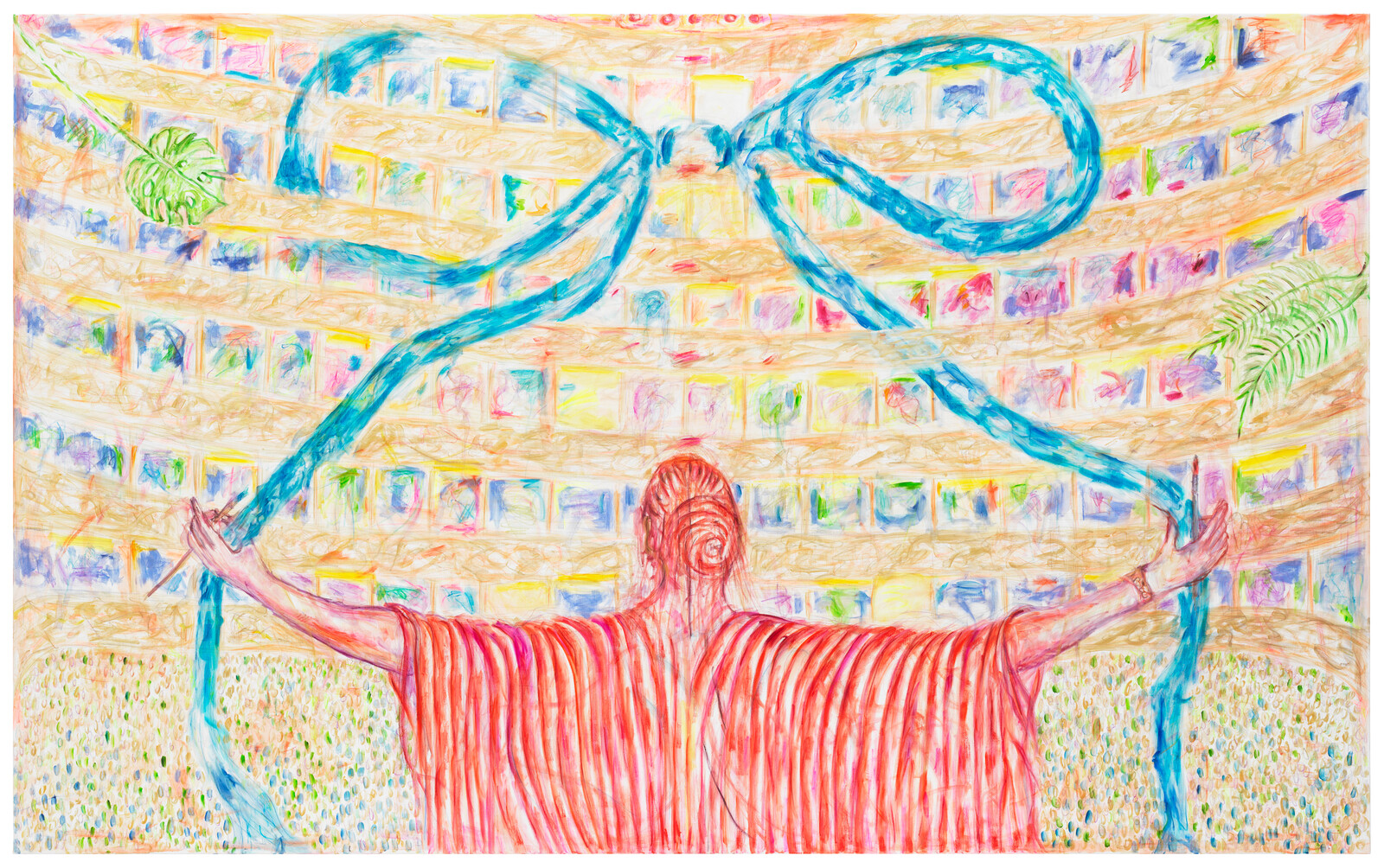

Moyra Davey’s “Forks & Spoons”

Maddie Hampton

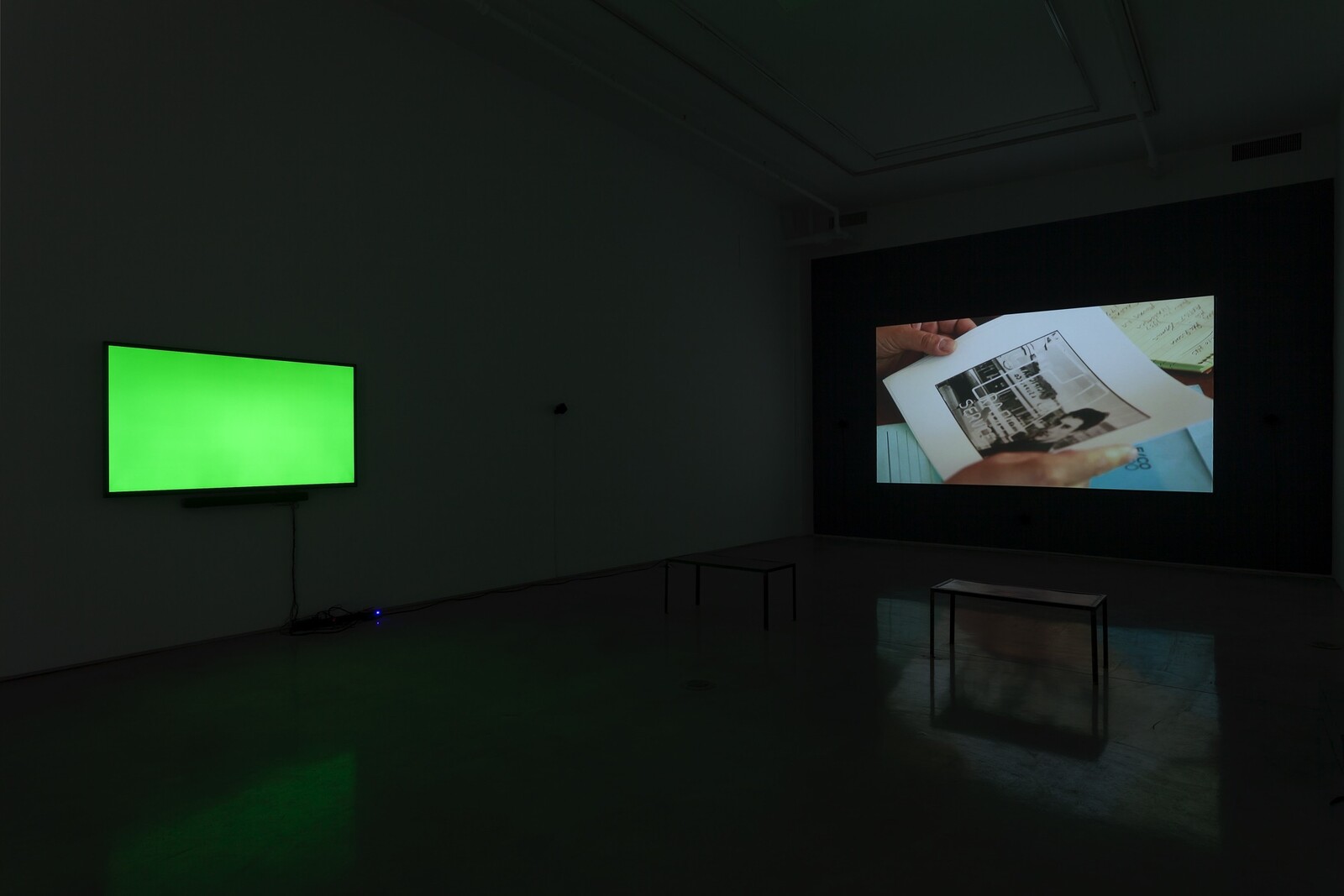

Moyra Davey’s latest film, Forks & Spoons (2024), studies the work of five photographers: Francesca Woodman, Carla Williams, Alix Cléo Roubaud, Justine Kurland, and Shala Miller. In her characteristic, essayistic style, Davey weaves together footage of herself pacing between moss-covered tree trunks to a voiceover narration that contextualizes the work of each artist within their respective biographies. Reprising a handful of motifs—close-ups of dog-eared book pages, sunlit corners, long shots of her hands methodically turning through photobooks, and other symbols of the daily and domestic—the film is screened alongside a curated selection of prints and photo books by each artist, so that it functions as a kind of coda for the wider exhibition. Though Davey maintains a porous boundary between cinematic and physical space, she accentuates the varying capacities of moving, still, and published images throughout the show, highlighting how each of these forms carries and conveys distinct meanings. Davey’s subject never shifts, but by translating it across forms, she successfully presents something closer to its totality.

Davey’s primary interest here is in many ways a style. Each of her chosen image-makers was or remains attuned to a particular pitch of self-capture: a feminized portraiture of long exposures, blurred movement, …

May 13, 2024 – Review

Vija Celmins’s “Winter”

R.H. Lossin

Vija Celmins’s latest show is at once an invitation to marvel at the perfect copy and to contemplate copying itself. The heavy rope that seems to hang down from the gallery ceiling is, in reality, a stainless-steel sculpture extending up from the ground (Ladder, 2021–22). Its adjunct, another piece of painted steel, Rope #2 (2022—24) sits coiled on the floor, playing its role as a fiber weave with equal conviction. The ropes, along with two other sculptures of exquisite verisimilitude, are enthralling in their own right. They also remind visitors that the surrounding paintings, which can easily register as minimal abstractions, are exercises in illusion and replication as well.

Umberto Eco once declared the United States to be a country “obsessed with realism, where, if a reconstruction is to be credible, it must be […] a perfect likeness, a ‘real’ copy of the reality being represented.” This cultural propensity for real fakes, Eco suggests, is at odds with the “cultured” America that produced Abstract Expressionism and modernist architecture. Celmins seems to think otherwise. “Winter” is full of Eco’s real copies, and Ladder may even be a reference to the “Indian Rope Trick” popular in magic shows. On the other hand, …

April 29, 2024 – Review

Grace Wales Bonner’s “Artist’s Choice: Spirit Movers”

Osman Can Yerebakan

Rhythm gives form to Grace Wales Bonner’s contribution to the Artist’s Choice series of exhibitions showcasing the “creative response of artists to the works of their peers and predecessors.” Not in the sense of a soundtrack or score, but rather in the British fashion designer’s focus on the different ways in which “sound, movement, performance, and style in the African diaspora” is translated into the works in MoMA’s collection. Tucked away in the more intimate first floor gallery, Wales Bonner’s exhibition offers a space of tranquility.

Terry Adkins’s Synapse (1992) hovers close to the ceiling, a yellow enamel-painted drum skin as perfectly rounded as the July sun. Beneath it is Adkins’s Last Trumpet (1995), a quartet of eighteen-foot-long horns crafted by attaching used trombone or sousaphone bells to brass cones. Standing like the enduring towers of an ancient civilization, the musical instrument-cum-sculpture resonates with the potential of its own activation (Adkins would play the instrument from its first presentation in 1996 through to his passing in 2014).

Earthy tones, dense textures, and subtle connections are the main ingredients in Wales Bonner’s alchemy. She has painted the gallery in tones of rusting metal, crystalizing sugar, and sanguine resin, lending the gallery …

April 25, 2024 – Review

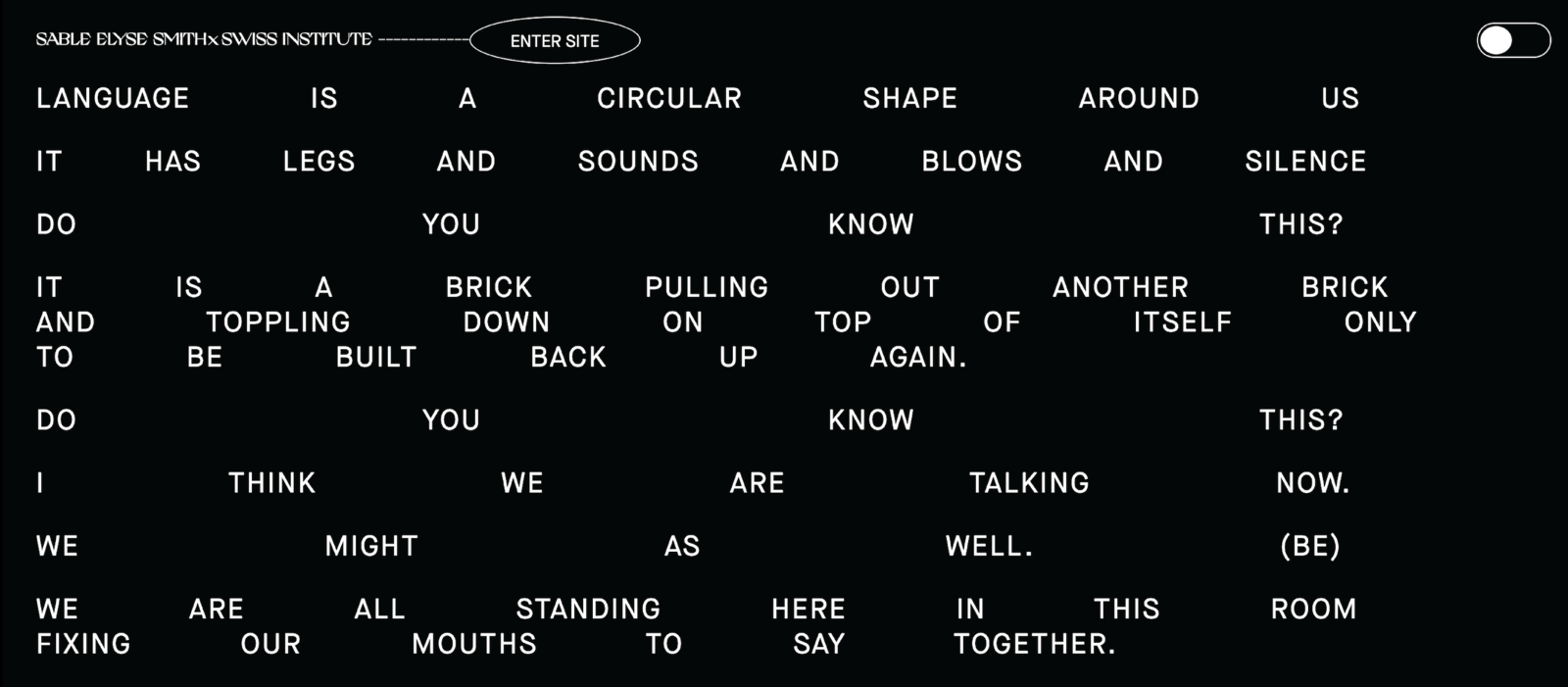

Raven Chacon’s “A Worm’s Eye View from a Bird’s Beak”

Rômulo Moraes

The flag-score that opens composer and sound-artist Raven Chacon’s exhibition at Swiss Institute—featuring work made over the past twenty-five years alongside a new sound and video installation—is a miniature portrait of his career. American Ledger No. 1 (Army Blanket) (2020), a graphic history of the United States in the form of an army blanket, is embossed with icons of waves, flames, police whistles, wood-chopping axes, and a fractured city skyline. Chacon’s main interests are all there: notation in the expanded field, the interplay of various mediums, the embeddedness of sound and landscape, and the malleability of map and territory. Working with post-Cagean aesthetics yet advancing them within a Diné/Navajo context, Chacon’s work suggests that notation is an imposition onto sound comparable to colonialism’s imposition onto the land.

The opening room contains the installation Still Life No. 3 (2015), in which a series of glass panels mounted onto the walls and engraved with white fonts tell the Diné Bahane’ creation myth, which describes the birth of light and color in worlds below ours, the raising of the waters, and the formation of mountains and celestial bodies. The transparent and reflective surface makes the glossy text intentionally difficult to read, as though …

April 12, 2024 – Review

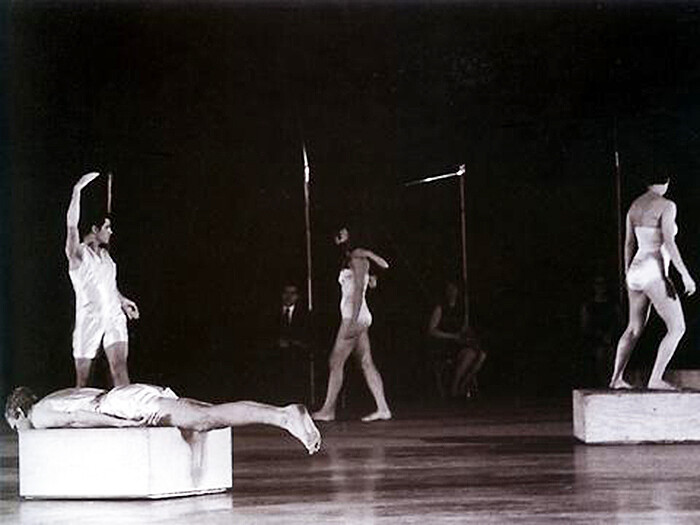

Joan Jonas’s “Animal, Vegetable, Mineral”

Filipa Ramos

Arranged into families following a meticulous taxonomic logic, the almost 300 drawings presented at Drawing Center reveal the extraordinary bestiary that Joan Jonas has been compiling over five decades. Jonas has a unique capacity to traverse and merge artistic fields as varied as performance, sculpture, environment, and video installation, but what is illuminated by this exhibition, carefully curated by Laura Hoptman with Rebecca DiGiovanna, is how drawing runs through, across, and within every means of her expression, accompanying the development of her career from the 1960s to the present.

The show also demonstrates how the artist has been bringing these disciplines together through drawing, as it becomes a practice akin to performing and editing, in a do-repeat-redo-repeat-erase-do-repeat method that connects the mind, body, and hand until the form emerges. Two drawings flank the entrance to the show (all works are untitled but classified by a reference number, in this case JJ084, circa late 1990s, and JJ085, from 2012), which also becomes its exit. These are two naked female torsos, as imposing and as head-, arm- and feet-less as the Winged Victory of Samothrace (190 BCE), made in the context of two live performances.

In parallel to this, Jonas has blurred …

April 5, 2024 – Review

Eva Gold’s “Shadow Lands”

Jenny Wu

The critique in London-based artist Eva Gold’s first US solo exhibition is spare and subtle. Consisting of six works on paper and two sculptural installations, the show conveys, in meticulous details and material choices, a message about the coercive economic power embedded in everyday cultural transactions. At the heart of the exhibition is “Pilot and Passengers” (all works 2024), a series of colored-pencil drawings of stills from Benny’s Video, Michael Haneke’s 1992 film about a violence-obsessed teenager disenchanted by his affluent upbringing, who murders a stranger in his parents’ home.

Gold’s understated drawings, hung in identical, nineteen-by-twenty-six-inch frames, line three of the gallery’s walls. In Haneke’s film, a low tracking shot follows several pairs of hands as Benny, the teenager, covertly collects money for a pyramid scheme called Pilot and Passengers that he introduced to his friends during school choir practice. Gold’s lighter, less saturated images emphasize general forms over details. From afar, viewers might mistakenly believe that they are spying on people holding hands. Up close, one still feels like a voyeur, since Gold’s static renderings allow the eye to linger on the creases in the fabric of the boys’ jeans, the threaded borders of their back pockets, the …

March 30, 2024 – Review

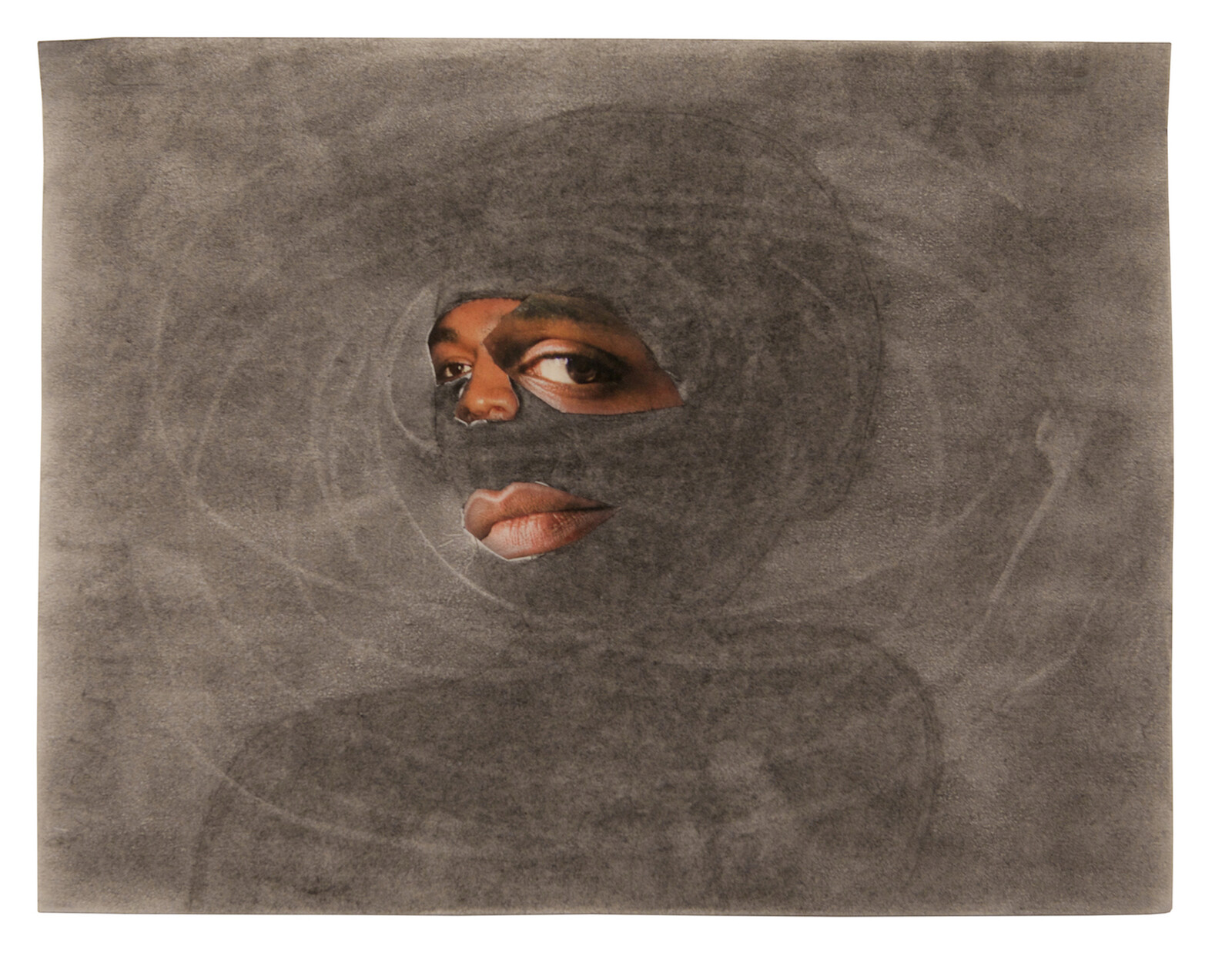

81st Whitney Biennial, “Even Better Than the Real Thing”

Ben Eastham

Walking through this survey of American art in the age of anger and anxiety, I kept returning to the curatorial statement’s seemingly innocuous proposal that new technologies are “complicating our understanding of what is real.” Are our horizons now so narrow, it occurred to me, that an algorithm’s ability to generate a derivative image is really more consciousness-expanding than such longstanding preoccupations of art as spiritual experience or the natural world? Or might the title’s appeal to something “better” serve to distract us from the already complicated and unarguably real events playing out beyond the walls of the museum, with which this biennial can seem reluctant to engage?

A generation of artists are, on the show’s evidence, retreating from a hostile public sphere into their own carefully cultivated worlds. This tendency manifests both in the valorization of marginalized identities through the adaptation of folk traditions to the present—notably ektor garcia’s use of crochet to articulate a nomadic cross-border experience—and in the tendency towards opacity, most explicitly in the panels of smoked black glass suspended precariously over the audience’s heads by Charisse Pearlina Weston (of [a] tomorrow: lighter than air, stronger than whiskey, cheaper than dust, 2022). Many of the realities …

March 15, 2024 – Review

Mary Helena Clark’s “Conveyor”

Chris Murtha

There’s a card trick midway through Mary Helena Clark’s Neighboring Animals (all works 2024 unless otherwise stated), a two-channel video projected into a darkened corner. While an elderly orangutan watches from the other side of his enclosure’s window, two human hands press a single playing card against the thick safety glass. Holding a stick in one hand, the ape nimbly picks up the card, now (miraculously!) on his side of the barrier. After giving it a sniff and twirling it around in his hands, he places it back on the glass, tapping it a few times with his makeshift wand—perhaps his attempt to send it back through the seemingly porous window. Clark edited this video—a zoo’s promotional clip gone viral—to preserve some mystery on behalf of the orangutan, cutting the ending so that the card, instead of falling to the ground, remains affixed to the glass.

A collage of sampled footage, still pictures, medical scans, and her own camerawork, Neighboring Animals scrutinizes the thresholds between inside and outside, human and beast. The left channel consists solely of yellow subtitles with no corresponding voice, a pastiche of quotations on the topic of disgust. Alongside illustrations of chained and leashed animals from …

March 12, 2024 – Review

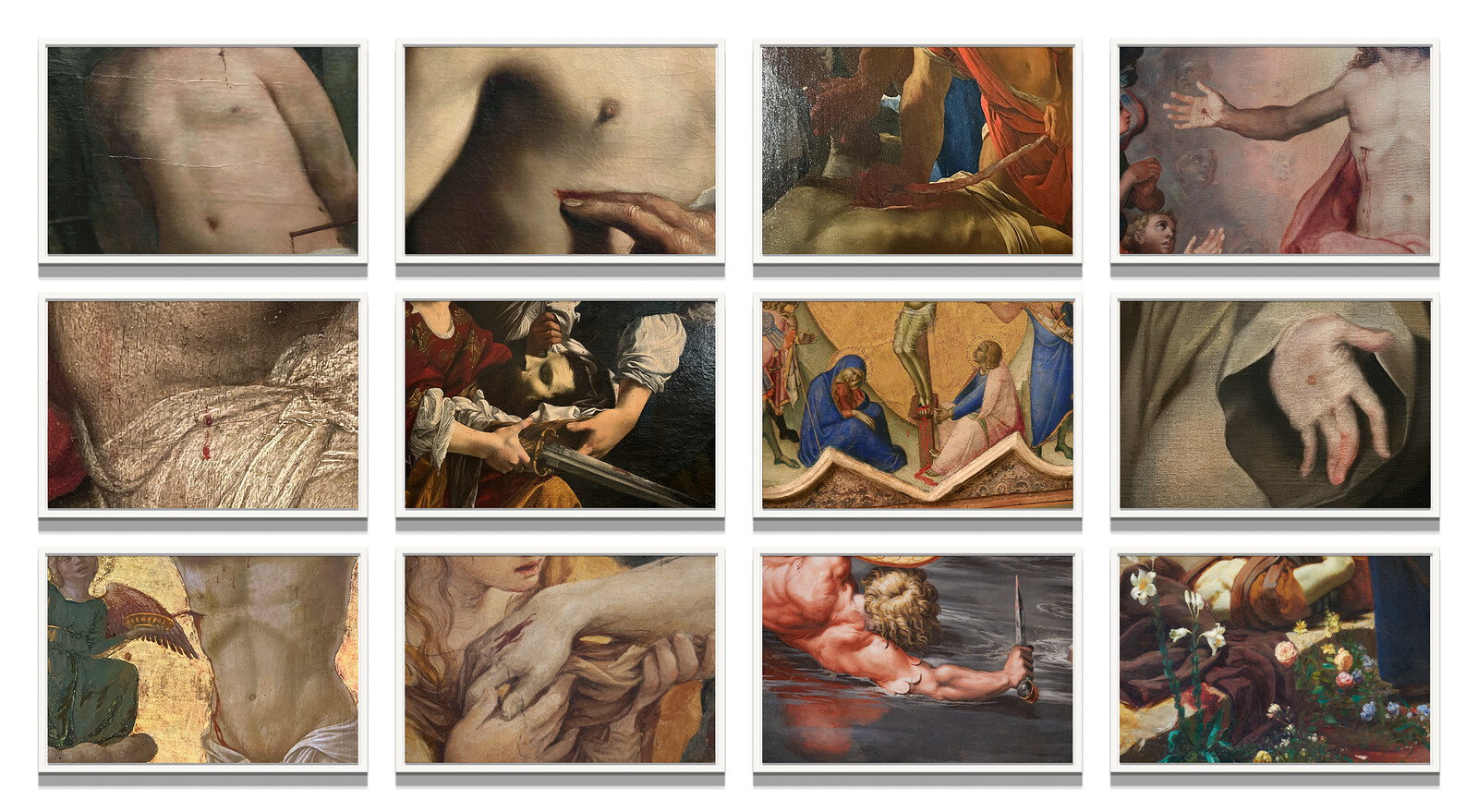

Catherine Opie’s “Walls, Windows, and Blood”

Sylvie Fortin

They say ghosts, vampires, and the soulless cast no shadows. Shot in a Vatican City emptied of visitors during the pandemic summer of 2021, Catherine Opie’s new photographs provocatively reshuffle different threads of her longstanding inquiries—the spectrum from transparency to opacity; communal spaces; the body as/and architecture; queerness and institutions. With its succinct, descriptive enumeration, the exhibition’s trinitarian title “Walls, Windows, and Blood” implies unsettling visual conversations to which she gives form with a selection of images from three new series (all works 2023), clustered in grids, lined up along walls, and proceeding in colonnades.

No Apology (June 5, 2021), a large photograph of Pope Francis delivering a speech from a top-floor window of his residence overlooking St. Peter’s Square, greets visitors. A lone white man dwarfed by statuary and muffled by the resounding whiteness of the colonnaded plaza, he floats above a blood-red banner bearing his coat of arms. In his short allocution, uttered in the wake of the traumatic discovery of unmarked graves at the former Church-run Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia, the pontiff acknowledged (apologies would have to wait) the Catholic Church’s complicity in both the colonial dispossession of Canada’s Aboriginal communities and the accompanying systematic …

March 8, 2024 – Review

Amalia Pica’s “Aula Expandida”

Noah Simblist

How might our understanding of education better incorporate communication, participation, and play? And what would be the consequences of that expanded approach? Such questions have been at the center of Amalia Pica’s work for many years, drawing partially on her early experience as a primary school teacher. Her first solo exhibition in New York attends to the manifold aspects of learning across a group of collages, sculptures, and video works organized around a new interactive installation.

Two understated large-scale graphite and watercolor drawings, School sheets in adjusted scale (or an exercise in how to go back to all the things I hadn’t thought of yet) #1 and #2 (both 2011), are based on notebook paper with “Rivadavia” printed in an elegant cursive in the margin. This references Bernardino Rivadavia, the first president of the London-based artist’s birth country of Argentina, using a font based on his signature. The stamping of state power into the very books in which young people learn how to write signals the reproduction of the ideological subject through a form of repeated inscription. This has chilling implications in the context of the military dictatorship (1976–83) into which Pica was born.

Her 2008 video On Education depicts …

February 27, 2024 – Review

Madeline Hollander’s “Entanglement”

Maddie Hampton

In profile, the six rounded disks at the center of Madeline Hollander’s latest exhibition appear glamorously extraterrestrial, the bright bulbs of the track lighting glinting in their polished chrome surfaces. Arranged in a grid on curved, white pedestals, the satellite-shaped objects are constructed from parabolic mirrors, a hole cut at the top of each to reveal a sinewy figure cast in aluminum, revolving atop a bifurcated circle of colored glass. Based on Hollander’s personalized notation system, specific silhouettes and colors correspond to a precise movement so that, taken in concert, the six figures play out an entire choreography, spinning perpetually in place.

Viewed at the right angle, the maquette doubles, ascending out of the mirror like a ballerina from a jewelry box to create the illusion of a perfect pas de deux—not a limb out of place, nor a posture skipped, as both “dancers” rotate in flawless synchronicity. Titled Entanglement Choreography I-VI (all works 2023), the objects are designed as miniaturized visualizations of quantum entanglement, the theory that two particles can be interdependent, mimicking one another across both space and time, the action of one entirely conditional on that of its partner. Quick and loose with her interpretations of the …

February 9, 2024 – Review

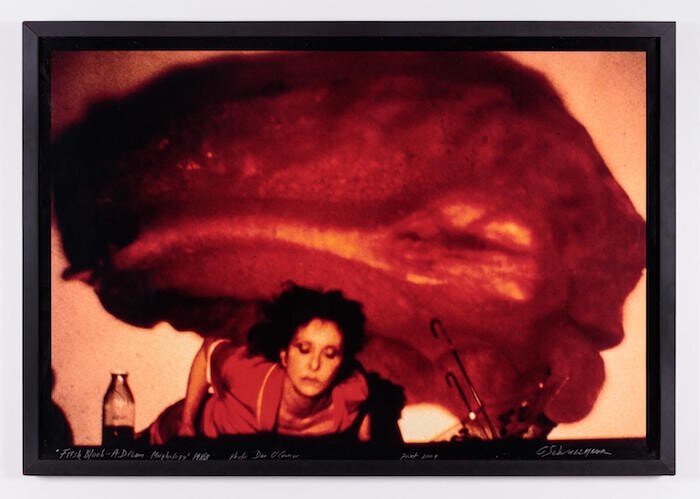

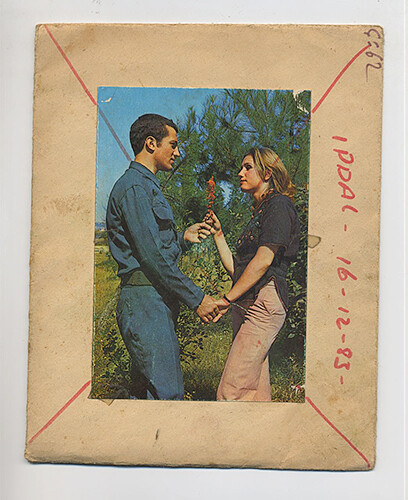

Astrid Klein

Xenia Benivolski

Astrid Klein’s photowork Untitled (Je ne parle pas,…) (1979) presents two cut-out images of Brigitte Bardot—posing in a baby doll dress and, again, coquettishly looking back over her shoulder. In broken, typewritten French and English are the words “je ne parle pas, je ne pense rien” (“I don’t speak, I don’t think”) and “to paint my life, to paint my life, so many ways.” It’s a fitting prelude to this exhibition, which is something of a house of mirrors. Trapped behind the museum glass, like sexy cats in apartment windows, large photographic works fill the walls, each featuring a beautiful woman while slyly reflecting the viewer. In Untitled (la sans couleur…) (1979), a reclining woman awkwardly turns her head to look at me with an enigmatic smile. Loosely draped in a sheet on an unmade bed in the dark, she is a body in waiting. These gazes are not exactly inviting; if anything, they somehow lack emotion, as the title reflects: “masks without color.” But there is something cool, even powerful, about their magnetic resignation. Like several in the show, the image is arranged with visible marker framing and taped sections, giving the impression that this composition sets the stage …

January 12, 2024 – Review

An-My Lê’s “Between Two Rivers/Giữa hai giòng sông/Entre deux rivières”

Jacinda S. Tran

In 1968, army photographer Ron Haeberle shot Vietnamese civilians indiscriminately massacred by US ground forces in the hamlet of Mỹ Lai. His photographs circulated widely—including a color photo of corpses strewn across a road featured in LIFE magazine that, in 1970, with support from the Museum of Modern Art, the Art Workers Coalition incorporated into an antiwar poster overlaid, in blood red, with the text “Q. And babies? A. And babies.” When MoMA withdrew its support for the poster, AWC staged a protest to illuminate board members’ tacit support of the war in Vietnam. The museum promptly assimilated AWC’s poster into their own collections, institutionalizing institutional critique.

Half a century later, MoMA exhibits “Between Two Rivers/Giữa hai giòng sông/Entre deux rivières,” a survey of multimedia works by Vietnam-born An-My Lê, whose large-format photographs are known for their staging and depictions of militarized landscapes. Lê focuses on what the visual reveals and obscures; how a range of quotidian landscapes may be conceived as “always already military.” Though Lê left Vietnam as a teenager after the fall of Saigon in 1975, the specter of war and its spectacularization informs her approaches to representation. In “Viêt Nam” (1994–98), Lê returns to her birth …

December 21, 2023 – Review

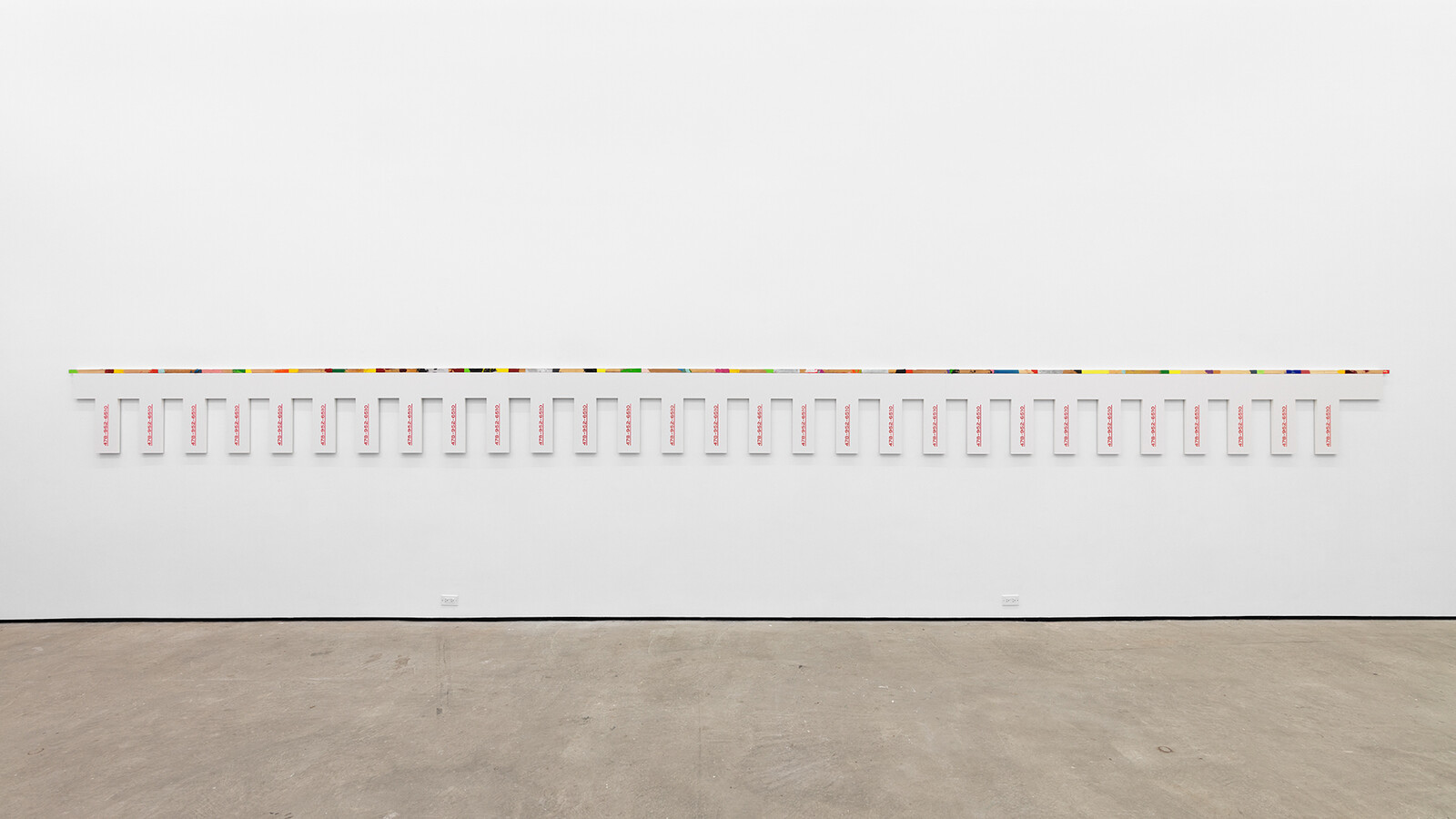

Andrea Bowers’s “Joy is an Act of Resistance”

R.H. Lossin

The first work that one encounters on entering Andrew Kreps’s gallery might be mistaken for an extension of the gallery’s commercial operations. Trans Bills (2023) consists of fifty-four black ring binders, arrayed on a shelf to the left of the front desk, labeled with the names of states that have passed legislation restricting the rights of trans citizens. The work’s blandness is perhaps the point. Quietly running in the background of clownish Republican performances of parental rights and viral videos of religious zealots is a legislative machine producing the reams of paper progressively restricting the rights of trans people to work, receive medical care, and live basic social lives. In a mere two years, 1,006 anti-trans bills have been introduced by state legislatures. An additional sixty-three have been introduced at the federal level.

At the back of the first-floor gallery is a 47-minute single-channel video of a trans prom organized by four teenagers as both an adolescent rite of passage and a protest—two things that are, for many trans youth, inseparable. The footage is visible from the gallery’s entrance, and the contrast between the young faces and the scale of adult animosity ranged against them is the show’s most valuable …

December 19, 2023 – Review

Mit Jai Inn

Jenny Wu

In Shirley Jackson’s allegorical short story “The Lottery” (1948), villagers gather for a game of chance in which they draw slips of paper, all blank but one, from an old black box. Children, adults, and elders alike, accustomed to the tradition, participate with a mixture of anticipation and boredom. The ending reveals that the prize, known to them all along, is the stoning of an unlucky villager. Mit Jai Inn’s first US solo exhibition also features a large quantity of “stones” and a lottery that, in subtler ways, uncovers a set of human behaviors integral to the functioning of society and politics. Here, the Chiang Mai-based artist, whose work is often framed as a form of social practice infused with Buddhist teachings, sets up a participatory piece titled after a recent sculpture series, Marking Stones (2022). Visitors are invited to submit pledges for “positive action” for a chance to win one of these sculptures.

The title of the series is a tenuous reference to the bai sema stones used by Buddhist communities in Southeast Asia to mark their territory: the sculptures are, in fact, fully functional baskets, lamps, and stools. Around two dozen of these candy-colored wares occupy a room …

December 15, 2023 – Review

Delcy Morelos’s “El abrazo”

Michael Kurtz

Here lie the ruins of the American avant-garde. Wood salvaged from an installation by Dan Graham, offcuts from a felt piece by Robert Morris, and scraps of flooring from a Dorothea Rockburne display. Mounds of soil recall Robert Smithson’s geological samples and rows of pipe echo Walter de Maria’s Broken Kilometer (1979) of brass rods lined up on the floor. These fragments now sit in darkness, illuminated only by four shaded skylights. They are arranged across the space along with sheets of corrugated metal, parallel stacks of wooden planks, and hundreds of small pieces of Colombian pottery. Everything is dark brown and sitting on a crust of mud which rises up the walls to a high-water mark, I later read, left after the gallery flooded during Hurricane Sandy.

Despite their simple forms and materials, the objects become mirage-like in this dimly lit monochrome expanse. Walking down the pier of clean floor that stretches into the room, I try to perceive the scale and texture of the things around me, but they evade my grasp. The light fades and they retreat further. Cielo terrenal [Earthly heaven] (2023), the first of two installations by Colombian artist Delcy Morelos at Dia Chelsea, is …

December 7, 2023 – Review

Shilpa Gupta

Paul Stephens

Recent New York Times headlines point to American perceptions of India’s increasingly prominent role in global affairs. “Can India Challenge China for Leadership of the ‘Global South’?” “Will This Be the ‘Indian Century’?” “The Illusion of a US-India Partnership.” “US Seeks Closer Ties With India as Tension With China and Russia Builds.” “US Says Indian Official Directed Assassination Plot in New York.” “An Indian Artist Questions Borders and the Limits on Free Speech.”

The last headline refers to Mumbai-based Shilpa Gupta, whose work obliquely explores the emergent global polycrisis (a term popularized by Adam Tooze) in which India plays a central part. Although Gupta’s art is deeply engaged with contemporary political events, it is not headline-driven. It resists didacticism, in part, through being polyvocal, as exemplified in her standout installation Listening Air (2019–23). Defying simple description and rewarding patient immersion, Listening Air consists of multiple microphones-turned-speakers that play songs of labor and resistance from around the world. As the songs fade in and out, listener-viewers in the dimly lit room slowly begin to perceive themselves as members of a temporary community. The effect is ethereal and meditative.

Gupta’s two concurrent New York exhibitions, at Amant and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, accord …

November 3, 2023 – Review

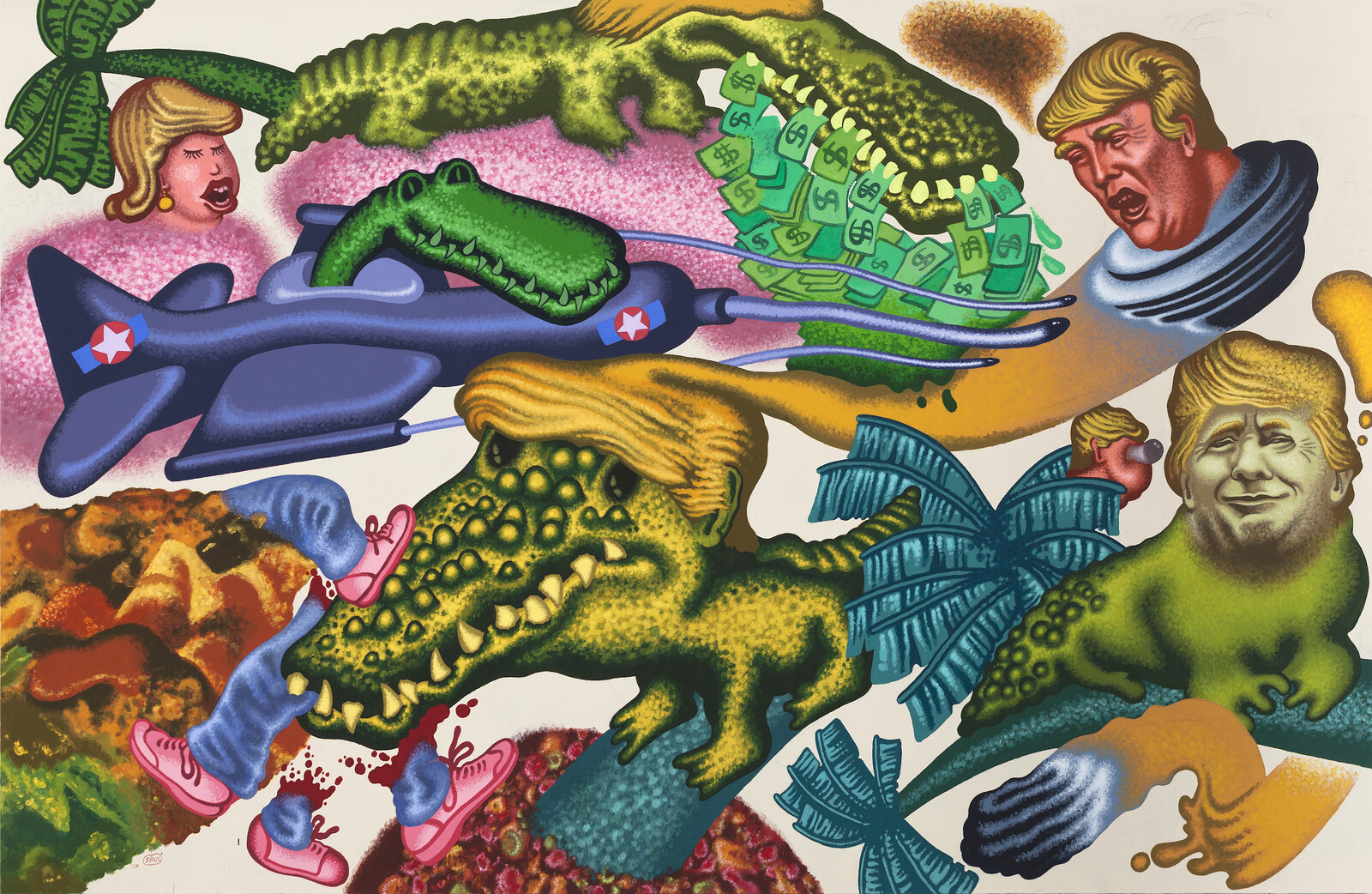

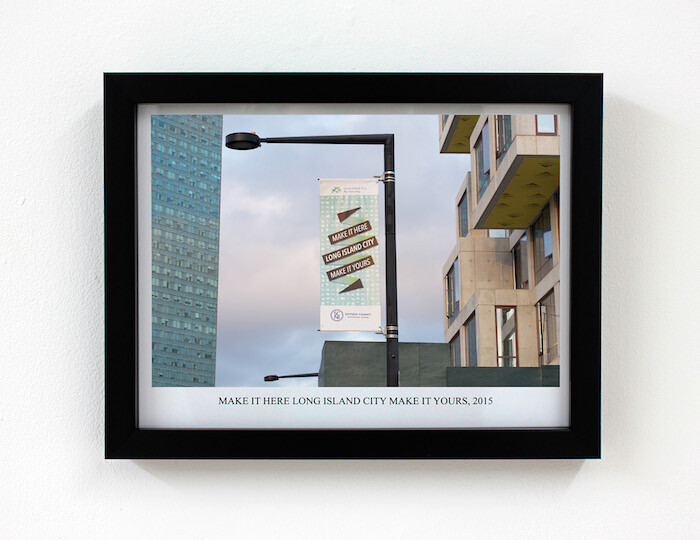

New Red Order’s “The World’s UnFair”

Stephanie Bailey

Occupying a pocket of undeveloped land in Long Island City, “The World’s UnFair” is a principled riot. Created by New Red Order (NRO), a “public secret society” facilitated by artists Jackson Polys, Zack Khalil, and Adam Khalil, this carnivalesque fairground, supported by Creative Time, is presided over by Ash and Bruno, a sixteen-foot animatronic tree with LED screens nestled in cellular tower branches and a furry five-foot tall beaver, respectively. The pair talk about the legacies of settler colonialism on the land where they stand, Lenapehoking—a forest, they say, the last time they met. America’s original multi-millionaire John Astor is mentioned: he made his fortune in the fur trade that all but decimated beaver populations, before acquiring land in Manahatta and making “a killing off renting to incoming settlers.”

The politics of land is at the heart of this roadshow. Staked into the earth is New Red Right to Return (2023), a wooden post with directional markers naming Lenape diasporic nations displaced by settlers due to the fundamental difference between the colonial European treatment of land as a commodity and the Indigenous American understanding of it as a communal resource. That discrepancy complicates the narrative that the Lenape sold Manahatta …

October 27, 2023 – Review

Candice Lin’s “Lithium Sex Demons in the Factory”

Jonathan Griffin

The story, as literary theorist Peter Brooks has observed, is today’s dominant cultural form. To Brooks, this “overabundance” of narrative is worrying: he criticizes the deference of virtually all strands of culture (not only literature, TV, and movies but art, museology, and—especially—news media) to the persuasive rhetorical power of the story. I share many of his concerns. “The universe is not our stories about the universe,” he writes, “even if those stories are all we have.”

In the artwork of Candice Lin, however—an artist who nests stories inside stories, who researches, remembers, speculates, and concocts in equal measure, all at once, without hope or intent to persuade—the story becomes a lubricative medium that enables the destabilizing of sense, the de-centering of singular subjectivities, and the unpicking of neatly tied conclusions.

“Lithium Sex Demons in the Factory,” the Los Angeles-based artist’s multimedia exhibition at the non-profit Canal Projects in New York, is near-impossible to summarize, except by telling stories. Let me start with one. In the 1970s, female workers at Japanese-operated factories in rural Malaysia experienced demonic possessions and spirit attacks. Workers at these factories hailed not just from Malaysia but China and India too, so bomohs (Malay shamans) and healers …

October 6, 2023 – Review

“Emerging Ecologies: Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism”

Matt Shaw

In March 1949, the cover of Popular Science magazine featured Ray Pioch’s brightly colored drawing of architect Eleanor Raymond’s Dover Sun House, a Massachusetts home developed with solar engineer Maria Telkes and heated exclusively by solar energy. Part Rockwell painting, part architectural section, and part science diagram, the illustration drew on Pioch’s experience drawing instruction manuals for the U.S. Navy during World War II. It shows an idyllic family in their well-tempered living room, kept warm by the energy captured through south-facing windows and stored in canisters of mirabilite, or Glauber’s salt, a mineral well suited to storing solar heat in the day and releasing it after dark. The cover represents the best image of post-war Pax Americana, but with a twist: a bright optimism that the sun was the future source of America’s energy needs, not oil.

The cover serves as a lively introduction to “Emerging Ecologies: Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism,” the inaugural presentation by the Emilio Ambasz Institute for the Joint Study of the Built and Natural Environment. Curated by Carson Chan, the show attempts to draw lines in the sand about what “ecology” and “the environment” mean in architecture from the 1930s to the …

October 5, 2023 – Review

Michael Rakowitz’s “The Monument, the Monster, and the Maquette”

Rachel Valinsky

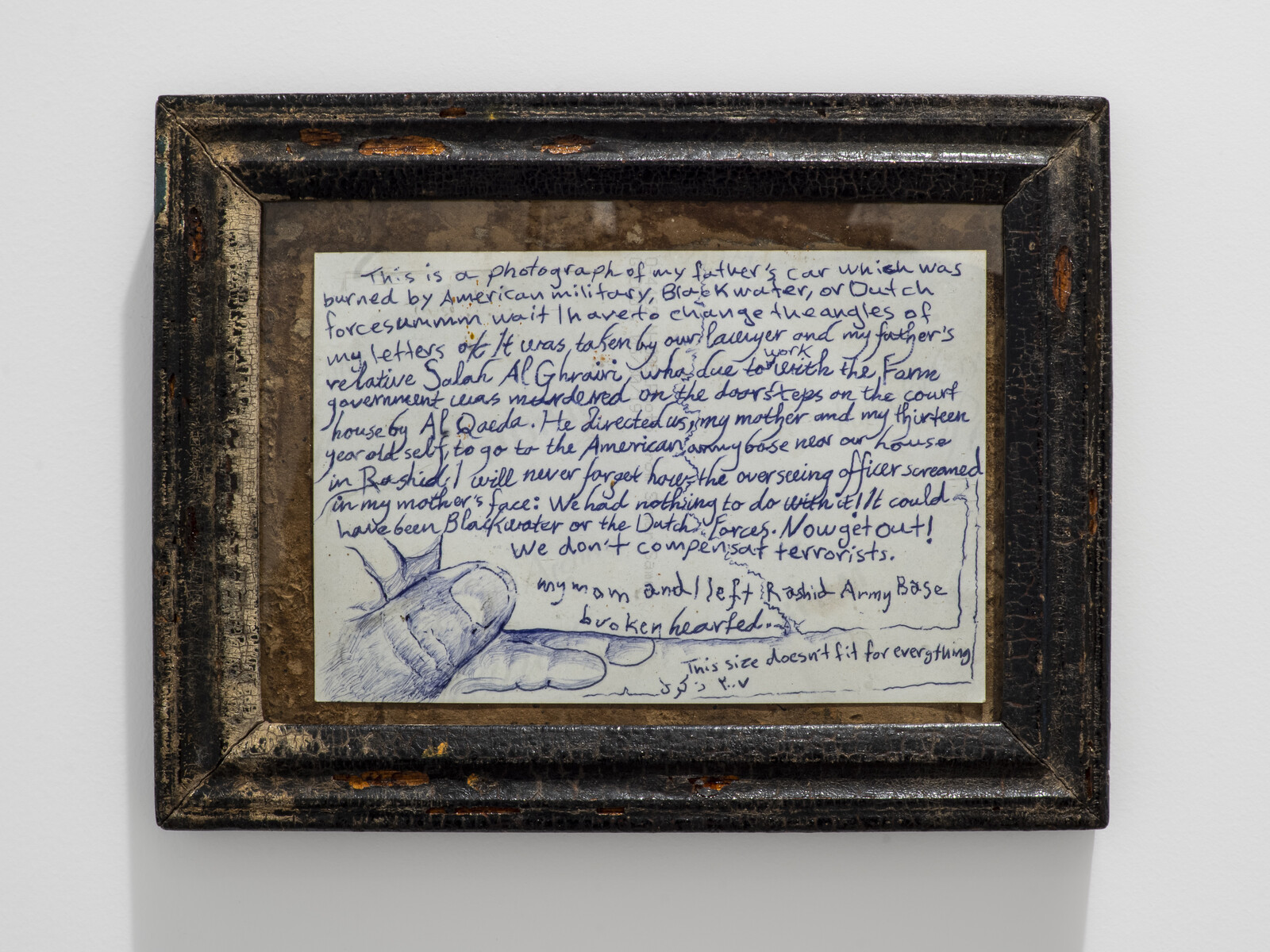

The exhibition’s title, alliteration and all, has the ring of an Aesopian fable. The Latin etymology of monument, Michael Rakowitz spells out on the edges of a sculpture, are trifold: caution (to remind, to advise, to warn), protest (demonstrate, remonstrate), monstrosity (monster). And indeed, around the gallery, the monstrous is everywhere in sight. Its forms are many: to the right, Behemoth (all works 2022), a colossal black plastic tarp obscuring the suggestion of an equestrian figure below rises tall only to fall to the ground as the fan powering its ascent clocks out. At the center, American Golem, poised on a decorative white wooden tabletop, an assemblage of found antiques and papier mâché sculptures (a strategy the artist has previously used for reproducing objects looted from Iraqi museums, highlighting the calls for their repatriation). The central figure, which stands on a stack of marble slabs, greets the viewer from the top of its bell-mold body and fired-clay mask—a copy of the Babylonian monster Humbaba. Gazing out at the viewer, its composite arms outstretched, it recalls Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus (1920), but even more grotesque. It doesn’t just stand on the wreckage of the past, propelled toward the future: it is …

September 29, 2023 – Feature

Valerie Werder’s Thieves

Wendy Vogel

In Valerie Werder’s debut novel Thieves, Valerie—an autofictional alter ego—chronicles her slide from disgruntled gallery copywriter to brazen shoplifter. At first she steals for the rebellious thrill of inhabiting other identities; eventually, and more abstractly, she steals to reclaim her time, words, and sense of self. Thieves centers on the New York blue-chip commercial art world, with its fussy idiosyncrasies and particular flavor of exploitation. But it is equally a novel about the fungibility of female identity—and a shrewd indictment of how language operates under capitalism.

Werder’s decision to write in a self-reflexive mode—a contemporary novel in the lineage of Semiotext(e)’s influential “Native Agents” series, edited by Chris Kraus and featuring authors such as Kathy Acker, Lynne Tillman, and Kraus herself—speaks to a desire to expose and explore the conditions under which Thieves was produced. Yet Werder is critical of how language is strategically deployed in the name of “authenticity,” both within the art world and literature. In Thieves, words bolster value, then drain themselves of meaning. People become expendable, while material things reinforce their self-worth. Over the course of the novel, Valerie becomes both a precious object and a voracious acquisitor. She enables, and is enabled by, a mysterious …

September 7, 2023 – Review

Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s “Radiant Remembrance”

Murtaza Vali

In Ken McMullen’s experimental film Ghost Dance (1983), Jacques Derrida proclaims that “Cinema is the art of ghosts, a battle of phantoms. It’s the art of allowing ghosts to come back.” This assertion of film’s proximity to the spectral plays out across Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s video installations, three of which anchor “Radiant Remembrance.” Blending animist beliefs held by Indigenous communities across Southeast Asia with the importance given to reincarnation within Buddhist theology, Nguyen uses film as a medium, not just as the material form of his art practice but as a channel through which to conjure forgotten pasts, narrate counter-memories, and confront historical violence and ecological destruction. After all, what are ghosts, if not simply our ancestors, and our memories of them, continuing to radiate their presence to us? What is remembrance if not simply a form of reincarnation?

These capacities are most clearly articulated in The Specter of Ancestors Becoming (2019), an immersive four-channel video installation about the descendants of the tirailleurs sénégalais—Senegalese soldiers conscripted to fight for the colonial French army in the First Indochina War who fathered children with Vietnamese women. That conflict ended a year before the 1955 Bandung Conference, which sought to build cooperation …

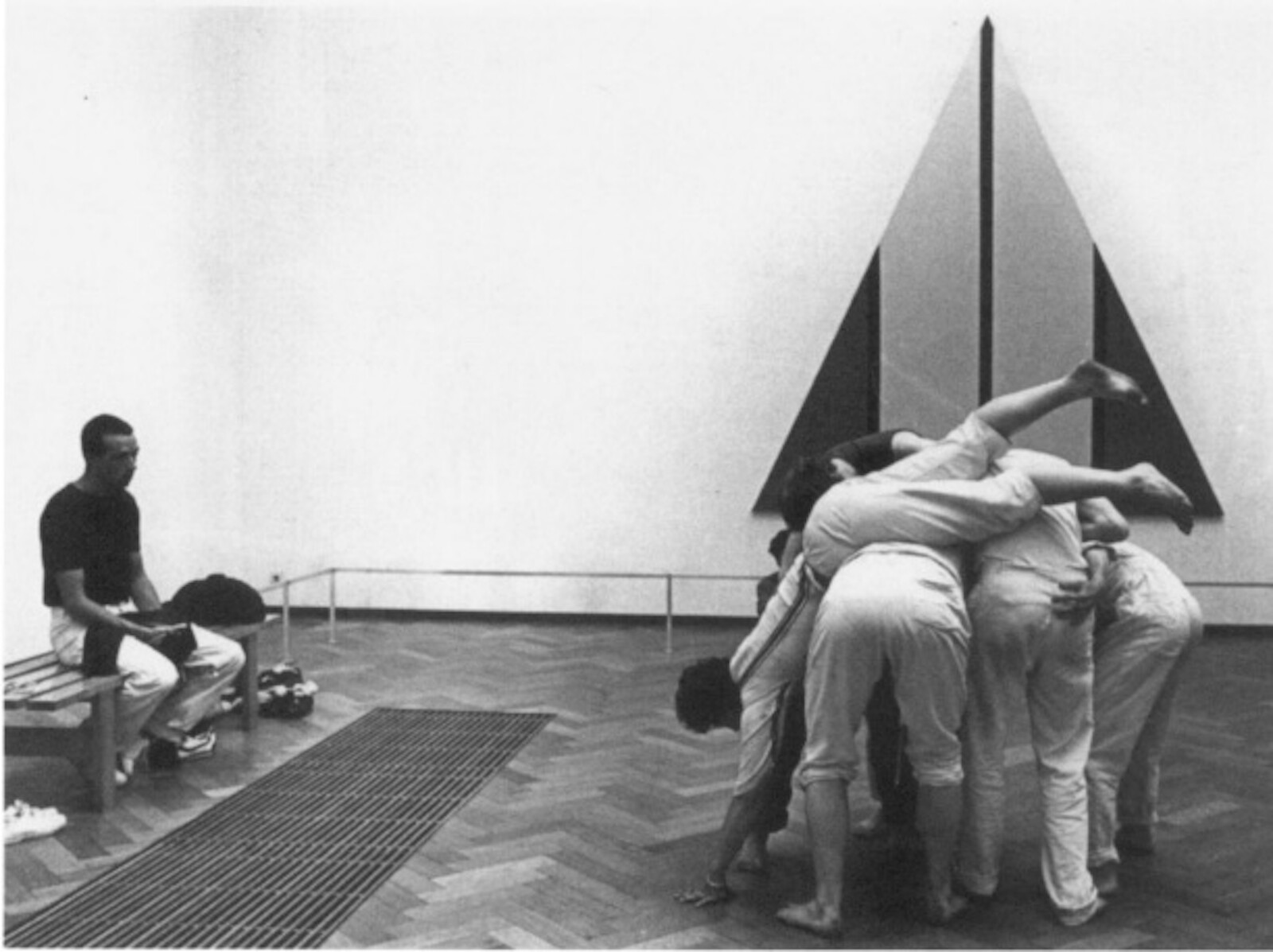

July 31, 2023 – Feature

Ethan Philbrick’s Group Works

Laura Nelson

There are many ways to move through and think alongside Ethan Philbrick’s Group Works. At first glance, it’s a book of academic theory coming out of performance studies. Following a “desire for collectivity,” Philbrick takes the small-scale formation of “the group” as the locus of inquiry. He enters the text with a tentativeness toward groups, recognizing the ways that they are frequently viewed with healthy suspicion or uncritical celebration. He asks:

What kind of good-bad thing is a group to do?

When do we do things in groups, and why?

How do we group, and how does that matter?

Moving with these questions, the book turns to artists experimenting with novel group formations in dance, literature, film, and music in the 1960s and ’70s. Each chapter pairs a “group work”—Simone Forti’s 1961 performance Huddle, Samuel Delany’s 1979 memoir Heavenly Breakfast: An Essay on the Winter of Love, Lizzie Borden’s 1976 film Regrouping, and Julius Eastman’s 1979 musical piece Gay Guerrilla—with contemporary works that re-imagine, re-perform, or dialogue with these experiments. Taken together, each pairing amplifies and extends the book’s central impulses to consider how groups assemble and disassemble. Along the way, Philbrick introduces a chorus of thinkers—theorists of community, theorists of in-operative community, theorists …

July 11, 2023 – Review

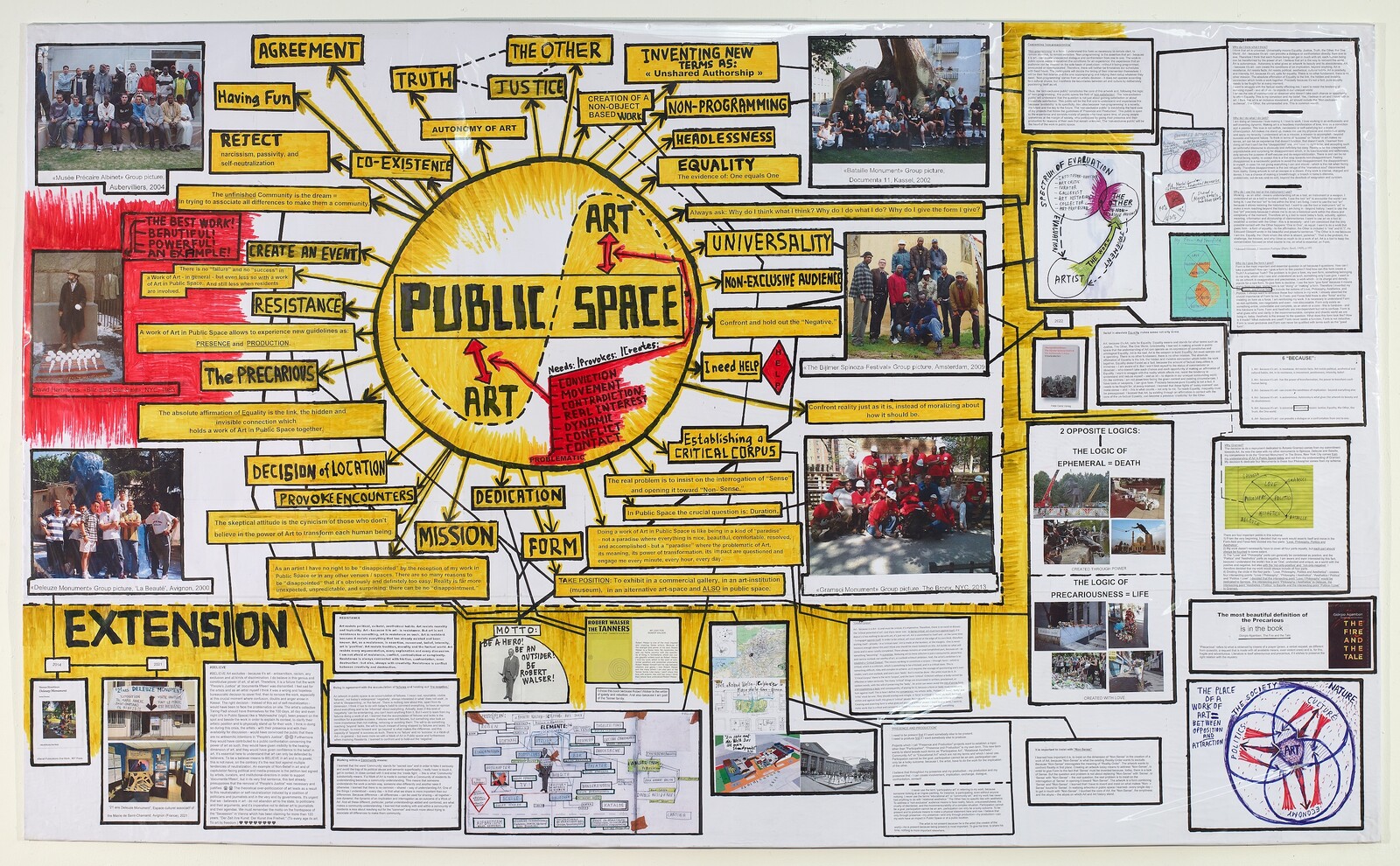

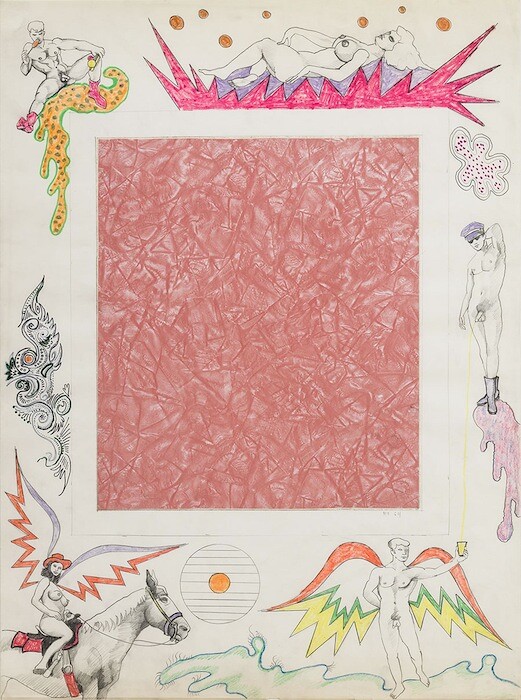

“Schema: World as Diagram”

Paul Stephens

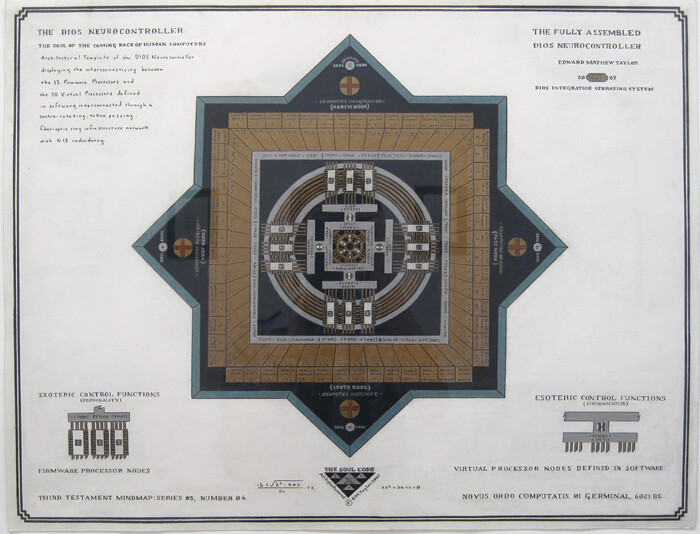

This exhibition of diagrammatic works juggles some of the most contested categories in contemporary art—and manages to keep all its curatorial balls in the air. Despite the broad sweep of its title, the show is tightly curated and requires multiple viewings for its full scope to set in. With an emphasis on painting, this meticulous grouping of fifty-plus artists undermines simplistic, outmoded art-historical binaries that oppose figuration and abstraction, conceptualism and expressionism, scientism and humanism. To call it expansive feels like an understatement.

The show takes its title from Thomas Hirschhorn’s Schema: Art and Public Space (2016–22), an exuberant multimedia collage-manifesto. Rudimentary and improvisational, Hirschhorn’s patchwork of ideas and contexts places the works in the show under a utopian-communitarian umbrella—exemplifying David Joselit’s claim in his 2005 essay “Dada’s Diagrams” that “the diagram constitutes an embodied utopianism.” Hirschhorn’s Schema might usefully be juxtaposed with Dan Graham’s 1966 work of the same name—sometimes taken to represent the apex of early informatic anti-figural conceptualism. (A show devoted to Graham’s Schema at 3A Gallery closed, coincidentally, several weeks before this exhibition opened.) Graham intended his work to be “completely self-referential” and meant to define “itself in place only as information.” Simply a text without …

June 23, 2023 – Review

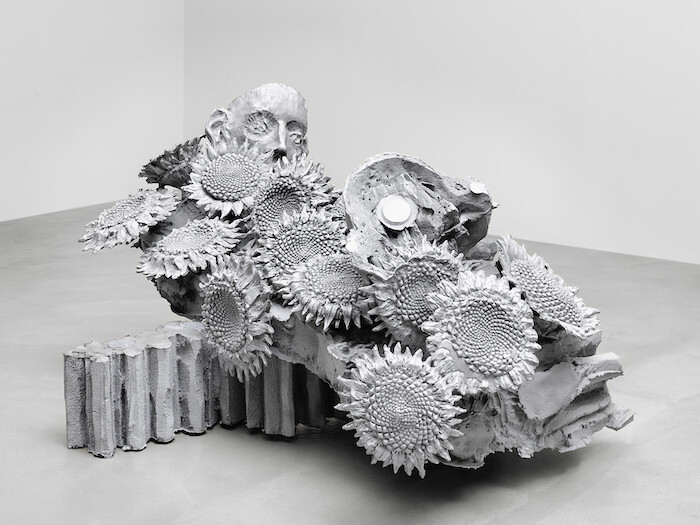

Aria Dean’s “Figuer Sucia”

Katherine C. M. Adams

One enters Aria Dean’s exhibition “Figuer Sucia” through Pink Saloon Doors (all works 2023) that open onto a vaguely neo-Western mise-en-scène. An ambiguous gray sculpture—heavily textured, with densely packed contours that evoke layers of folded skin and the crushed musculature of a horse—sits on a wooden pallet at the center of the room. This mildly cubic, contorted sculptural figure (FIGURE A, Friesian Mare) appears to be cowering, its subject’s equine body nearly unrecognizable. Dean’s recent exhibition at the Renaissance Society, “Abattoir, U.S.A.!,” took the slaughterhouse as a way to examine the limits of subjecthood. Its central film work walked the viewer through the environments of factory farming. While Abattoir, U.S.A.!’s featured architecture was outfitted for the killing of animals, the rooms it showed remained empty, painting a backdrop of violent and eerie subjectification. Like that project, “Figuer Sucia” is implicitly connected to Dean’s longstanding reflections on how Blackness is conditioned for and as social material. The contorted not-quite-object, not-quite-subject of FIGURE A might seem to show the implied, absent victim of that prior project. Yet “Figuer Sucia” calls the source of such brutality into question. It examines a violence that is not only in the scene we are witnessing, but …

June 14, 2023 – Review

Paige K.B.’s “Of Course, You Realize, This Means War”

Travis Diehl

At the opening, the red and white helium balloons were in everyone’s face. Now, at the show’s close, they’re at your feet, like a deflated Great Pacific Garbage Patch, pressing visitors closer to Paige K.B.’s intricate collages on wood panels, pastiches of art-historical material, and political sound-bites; closer to the web of found objects and deadpan references supplementing the paintings, to the sour red walls they hang on. The balloons make it hard to take in the show from a safe, not to say critical, distance. No measured overview allowed, only deep diving, unpacking, conspiring. The balloons suggest a constellation so dense and rubbery it’s a blob, the trampled ribbons like the red yarn in the disgraced detective’s storage unit—their significance all wadded up and too close to see.

Maybe that’s too much weight to attach to party decorations that never got cleaned up. But why weren’t they cleaned up? Why are they on the checklist, inaccurately, as 99 Red Balloons of Diplomacy (all works 2023 unless otherwise stated): “Thirty-one red balloons,” when some are white? A checklist on a PDF dated May 17—two weeks after the opening? But the balloons fit the vibe. They insinuate themselves into a scenography …

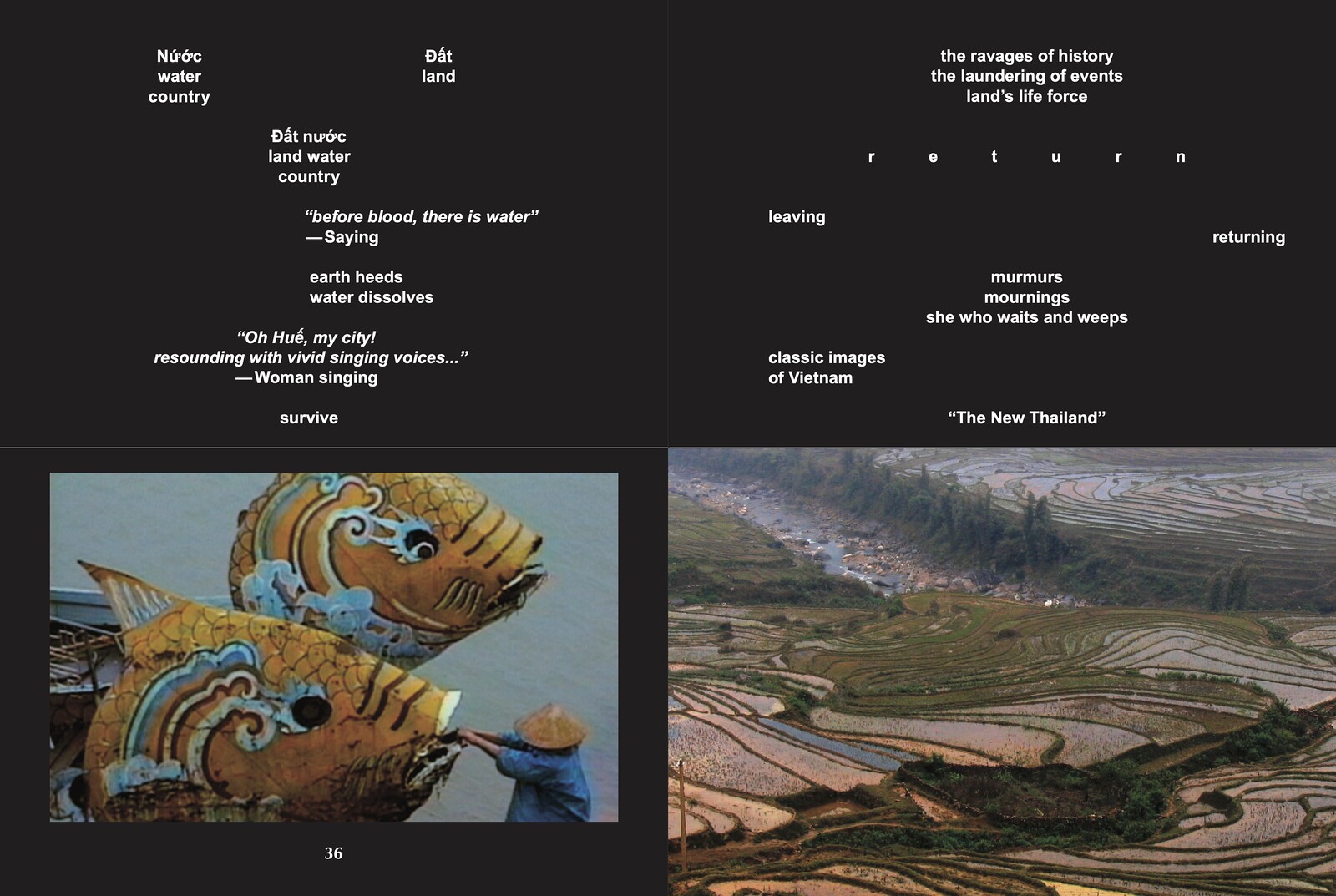

June 8, 2023 – Feature

Trinh T. Minh-ha’s The Twofold Commitment

Patrick J. Reed

The Twofold Commitment revisits Trinh T. Minh-ha’s time-dipping Forgetting Vietnam (2015), a documentary feature about the mythical origins of Vietnam. Which is to say, it’s a book about a film which reflects on what the name of a country evokes of the history, people, and cultures associated with it. Seven interviews conducted between Trinh and eight media scholars and critics compose half of the book. Each approaches the filmmaker and writer’s work from a different tack, focusing on aspects of Forgetting Vietnam that are representative of her multi-hyphenate career. Irit Rogoff, for example, homes in on what it means to make a film for the feminist viewer, while Stefan Östersjö concentrates on the multi-sonic soundscapes within it. And Lucie Kim-Chi Mercier’s discussion, “Wartime: The Forces of Remembering in Forgetting,” provides important historical background about the country in question.

As a filmmaker and theorist, Trinh strives to disavow classification and impress upon her audience the necessity of the extra- and non-categorical. Thus certain terminology, like some already employed in this review, requires inverted commas more often than not. “Documentary” refers to a moving-image essay composed of Hi8 footage from 1995 and HD footage from 2012, which Trinh gathered on separate visits …

June 7, 2023 – Review

Juliana Huxtable and Tongue in the Mind

Harry Burke

As a teenage indie fan, I spent countless hours on peer-to-peer file sharing platforms like LimeWire and Kazaa, and later blogs and MySpace pages, on which I discovered bands like the Velvet Underground, Boredoms, and Gang Gang Dance. Each products of art scenes, these acts not only soundtracked my adolescence but, by showing me alternative ways of listening and living, sparked my curiosity for contemporary art.

In their New York City debut at National Sawdust early last month, Tongue in the Mind forged a novel branch in the art-rock lineage. The project follows almost ten years of collaborations between artist Juliana Huxtable and multi-instrumentalist Joe Heffernan, also known as Jealous Orgasm, who are joined by DJ and producer Via App on electronics. Huxtable’s art practice spans creative registers, and muses on themes including furry fandom and the psychedelic edges of queer desire. An acclaimed DJ, her inventive sets defy genre and expectations, whether she’s playing Berghain or the basement of a bar. Tongue in the Mind synthesizes these pursuits, and evidences the trio’s musical and artistic maturation.

The performance was the finale of “Archive of Desire,” a week-long ode to the Alexandrian poet Constantine P. Cavafy (1863–1933), programmed by the …

May 3, 2023 – Review

Bispo do Rosario’s “All Existing Materials on Earth”

Elena Vogman

A number of extravagant garments, marked by generous color schemes and complex embroidery, open the first of three luminous rooms in “All Existing Materials on Earth,” curated by Tie Jojima, Aimé Iglesias Lukin, Ricardo Resende, and Javier Téllez. Its central piece, Manto da apresentação [Annunciation Garment], catches the eye with a multiplicity of details, inscribed with colored threads against a light-brown ground: signs and drawings of objects, names, numbers, abbreviations, and streets of Brazilian cities, utensils, boats and a model of a large sailing ship.

A photographic portrait of the artist wearing his magnum opus reveals not a fashion designer but a Brazilian psychiatric patient. The descendant of Black slaves, Arthur Bispo do Rosario (1909/11–1989) spent forty-one years of his life in mental health institutions while accomplishing his “mission.” On the side of the short exhibition text, another mugshot-like portrait of the artist is displayed on the patient card from Colônia Juliano Moreira, the hospital where Bispo was interned. He is described as “indigent,” a wandering Black beggar bearing no documents. The card repeats the police record from December 1938, when Bispo was arrested in Rio de Janeiro and diagnosed with “paranoid schizophrenia.” It was the month of Bispo’s revelation: …

April 21, 2023 – Review

“Refigured”

Travis Diehl

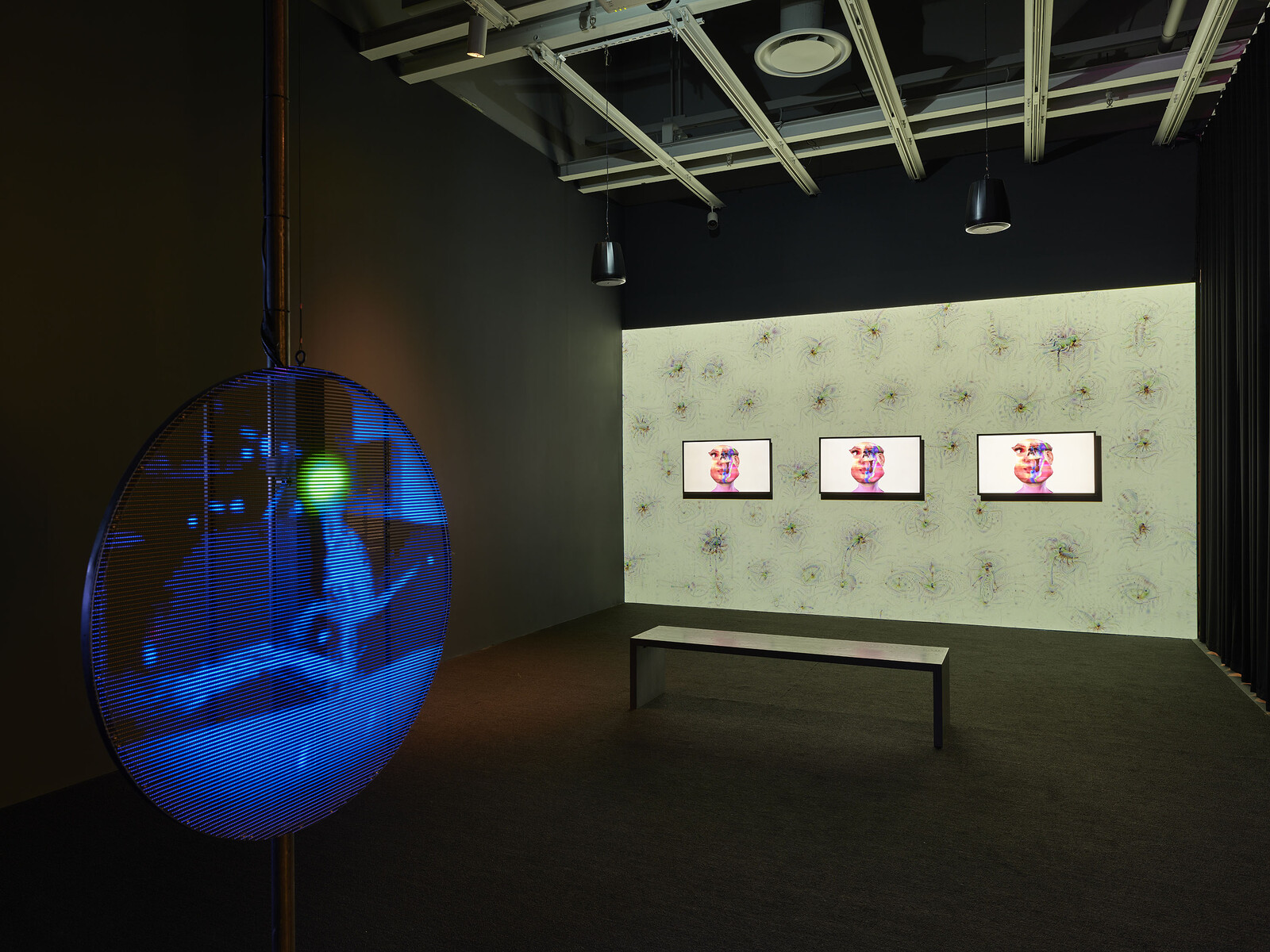

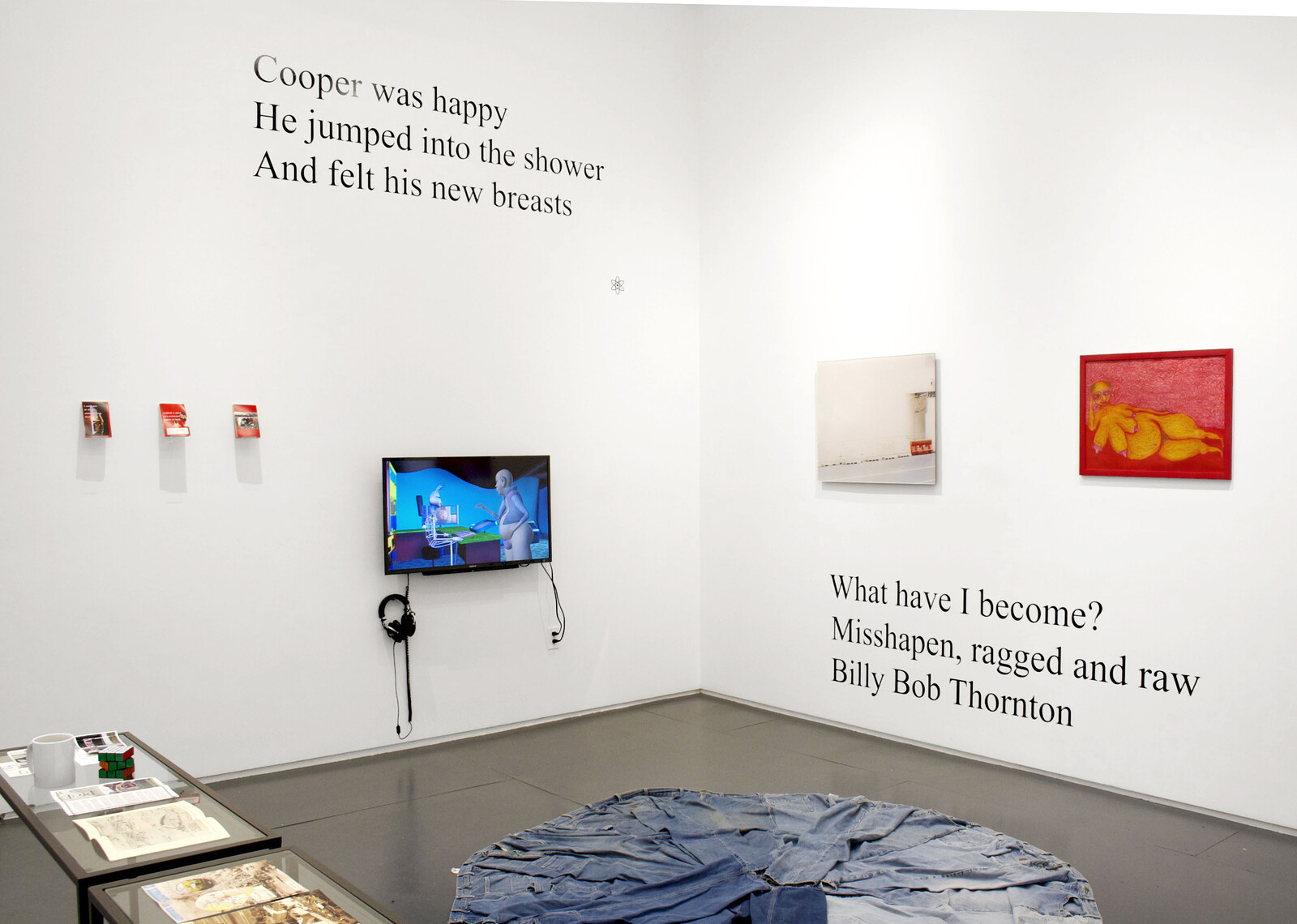

Among a spring flush of screen-, code-, and tech-related museum shows, “Refigured” at the Whitney stands out for its concision. The exhibition’s frame may seem vague—the human figure vis-a-vis technology at times verges on a universalized body—but the five works by six artists pulled by in-house curator Christiane Paul from the Whitney’s holdings maintain a fairly tight focus on the physical possibilities of digital bodies, from statues to demigods to talking heads. In Auriea Harvey’s Ox (2020) and Ox v1-dv2 (apotheosis) (2021), for instance, a muscular, berobed humanoid called Ox—which the wall label describes as an avatar for the artist—appears three times over: a pigmented statuette around 20 cm tall, a 3D model presented on a monitor, and an AR version pinned nearby and visible through an iPad tethered to its plinth. The artist’s intentions notwithstanding, Ox exists in digital and psychic “space” as a concept, a potentiality, and these various renderings are all concessions to display in a physical room.

In fact, as each new struggling trillion-dollar metaverse venture demonstrates, even state-of-the-art interfaces between the digital and physical “realms” remain pretty clunky (and the hardware here is not state of the art). The redundancy of Ox means there are …

April 7, 2023 – Review

“Cinema of Sensations: The Never-Ending Screen of Val del Omar”

Herb Shellenberger

A quick survey of a handful of my peers—among them several experimental filmmakers, curators, and academics—revealed that none of them recognized the name José Val del Omar (1904–82). This came as a surprise to me, given that Val del Omar is perhaps the most foundational filmmaker of Spanish avant-garde cinema. My peers’ responses were ample if anecdotal evidence that the Museum of the Moving Image’s “Cinema of Sensations: The Never-Ending Screen of Val del Omar” is not only much needed; it should also provide an eye-opening look at the work of a visionary artist who is too little-known outside his home country—even to those who are invested in the subject of experimental film.

“Cinema of Sensations,” in the museum’s temporary exhibition gallery, demonstrates that Val del Omar was not just a filmmaker but a technician and inventor, cultural critic and theorist, and a trailblazing artist whose work and ideas spilled across many forms and media. This chronological exhibition opens with Val del Omar’s first films, made in rural towns that he visited during the early 1930s as part of the Misiones Pedagógicas (Pedagogical Missions) literacy campaign. It closes with the techno-futuristic experiments developed at his P.L.A.T. lab, a live-in studio space …

March 24, 2023 – Review

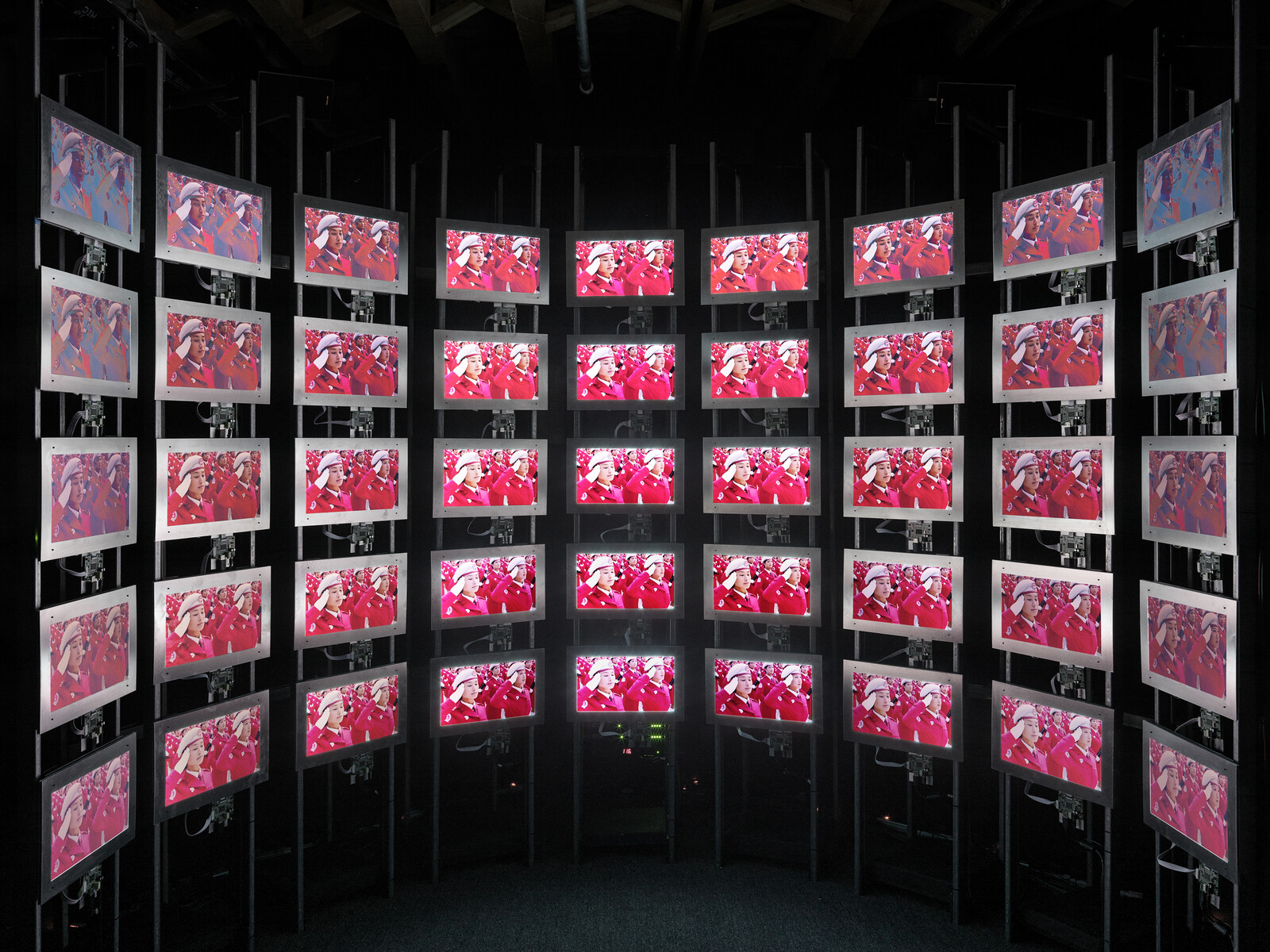

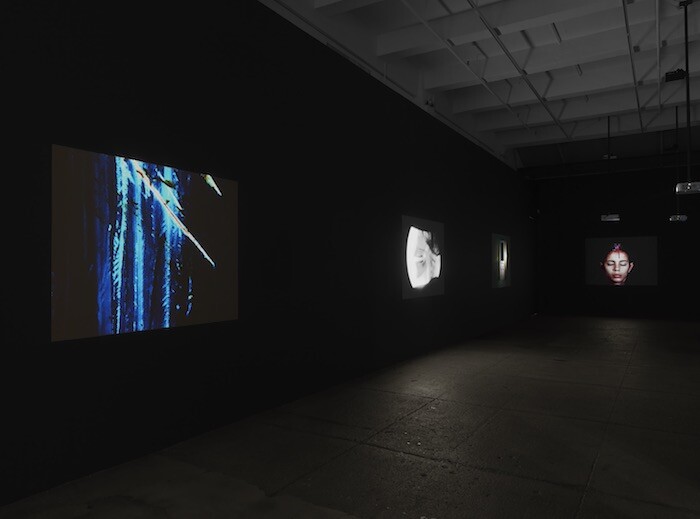

“Signals: How Video Transformed the World”

Dennis Lim

“Video is everywhere,” begins the wall text at the entrance to MoMA’s largest video show in decades, as if on a cautionary note. Equally, to borrow an aphorism from Shigeko Kubota, subject of a recent MoMA exhibition: “Everything is video.” (It is worth noting that Kubota said this in 1975.) In tracing the evolution of video from its emergence as a consumer technology in the 1960s to its present-day ubiquity, “Signals” covers a dauntingly vast sixty-year span. A lot happened—not least to video itself—in the years separating the Portapak and the iPhone, half-inch tape and the digital cloud, and as the material basis of video changed, so too did its role in daily life.

This sprawling, frequently thought-provoking show proposes a path through these dizzying developments by considering video as a political force. In their catalog essay, curators Stuart Comer and Michelle Kuo call the exhibition “not a survey but a lens, reframing and revealing a history of massive shifts in society.” Not incidentally, this view of the medium—as a creator of publics and an agent of change—is in direct contradiction to a famous early perspective advanced by Rosalind Krauss, who in a 1976 essay wondered if “the medium of …

March 14, 2023 – Review

Refik Anadol’s “Unsupervised”

R.H. Lossin

It is widely accepted that propaganda makes for bad art. But propaganda is not always an Uncle Sam poster. Sometimes it is a towering, spectacular argument for the supremacy of the machine; an exercise in post-industrial American triumphalism, surveillance technology, and repressive deep-state R&D disguised as visually appealing, non-referential images. The United States has a long history of cultural campaigns aimed at furthering its imperial goals. The Museum of Modern Art’s historical connection to the CIA is—like Radio Free Europe and the Congress for Cultural Freedom—among the more notable examples of the government’s intervention in our civic life. But despite our awareness of these operations, the potential propaganda function of abstract and non-representational art rarely enters into its critical reception and evaluation. Perhaps the idea of propaganda is so thoroughly wedded to realism in the American imagination that MoMA’s collection seems unimpeachable. Maybe the term “propaganda” has become, through popular use, something that is only used by one’s political opponents. While it is tempting to argue that cultural control is now mediated by a confusing, irresponsible, and diffuse spectacle of corporate greed, Refik Anadol’s “Unsupervised” (2022) suggests that we should reconsider the utility of a more vulgar analysis of visual …

March 8, 2023 – Review

Charles Atlas’s “A Prune Twin”

Erik Morse

When Charles Atlas quit as filmmaker-in-residence at the influential Merce Cunningham Dance Company, in 1983, after more than a decade, he decided to embrace a younger generation, a different continent, and a more public medium. These changes coalesced around the Pandean figure of Michael Clark, a former prodigy of London’s Royal Ballet School who in 1984 began to sketch out a punk- and club-inspired choreography with his own newly founded dance company. That same year, Atlas produced two works of videodance—a genre of experimental dance film, popularized by Atlas and Cunningham, in which choreography is designed for the camera rather than the stage.

These two films, Parafango (1984) and Ex-Romance (1984/1987), feature performances by Clark, Philippe Decouflé, and former Cunningham dancer Karole Armitage. They are set in vernacular places such as airport lounges and gas stations, and are spliced with news footage, presenter commentary, and video transmission signals. Both spotlight Clark as the enfant terrible of London’s post-punk underground, and the combination of his fauvist choreography with Atlas’s camp visuals captured a Baroque aesthetic that would characterize its queer subculture throughout the decade.

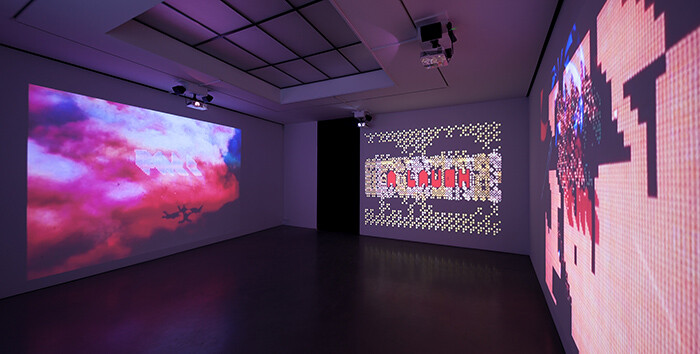

A Prune Twin, originally commissioned by London’s Barbican in 2020, consists of a multi-channel video projection sourced …

February 17, 2023 – Review

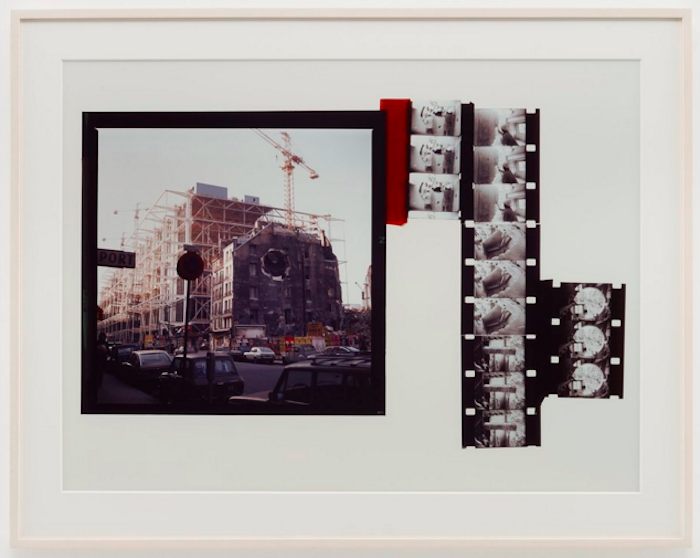

Gordon Matta-Clark and Pope.L’s “Impossible Failures”

Katherine C. M. Adams

Gordon Matta-Clark’s film Bingo X Ninths (1974), which features a precise dismantling of all but the core of an abandoned house, has been projected at large scale along the first wall of 52 Walker. The door to the exhibition space intersects the projection, such that gallery visitors irrupt onto the image as they enter and exit. A perfectly circular hole, cut straight through the same gallery wall, also interferes with the clean transmission of the film. A layer of dust from this incision lines the gallery floor.

It’s tempting to view such strategies as a literal self-reflexivity built into the gallery design: Matta-Clark’s canonical building cuts overflowing onto the gallery’s walls, making their mark on the present architectural space. Yet the pairing of Matta-Clark and Pope.L for “Impossible Failures” performs a different function, complicating Matta-Clark’s practice on a more fundamental plane. Here, Matta-Clark appears to work vertically, in the air, through various forms of physical suspension, while Pope.L works laterally, low-to-the-ground, worm-like. Drawings by Matta-Clark with subjects such as High Rise Excavation Diving Tower (1974) show lofty engineering schemes that seem to resist the pull of gravity. The artist’s three exhibited films all emphasize, to varying degrees, aerial vantage points …

February 10, 2023 – Review

Luis Camnitzer’s “Arbitrary Order”

Paul Stephens

Luis Camnitzer’s A to Cosmopolite (2020–22) is a marvel of precisely executed conceptual art—or as Camnitzer might prefer, “contextual art” (a term he has advocated since the 1960s). Writing through a 1972 Webster’s unabridged English dictionary, Camnitzer covers the gallery walls in prints that match each definition to a screenshot of the first search result from Google Maps that corresponds to it. The title of the exhibition is something of an oxymoron: by combining two classification systems, the cartographic and the lexicographic, Camnitzer reveals a myriad of cultural and political interconnections. The search results in A to Cosmopolite are proximate to Camnitzer’s own location in Great Neck, New York, thus making the project personal as well as global. Someone in Camnitzer’s digital orbit named their corporation “Aleatoric Media, LLC,” and that entry, like many others, stuck out to me as a viewer. I found the best way to explore the work was to read, in alphabetical order, every red location name—which took approximately an hour. When a name intrigued me, I consulted the corresponding definition and took a photo with my phone—reincorporating the physical work on the wall into my own personal datasphere. This work is, importantly, a remediation of …

January 24, 2023 – Review

Andrea Fraser

Wendy Vogel

In 2005, Andrea Fraser’s consideration of the art world appeared to undergo a transformation—from externalization to embodiment. “If there is no outside for us, it is not because the institution is perfectly closed,” she wrote. “It is because the institution is inside of us, and we can’t get outside ourselves.” This sentiment of identity entrapment is nowhere more evident than in her latest work, This meeting is being recorded (2021), in which the shape-shifting artist portrays seven white women in a closed-door meeting about internalized racism. The ninety-nine-minute video—which is based on real conversations and debuted at the Künstlerhaus Stuttgart before traveling to the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles last year—forms the nucleus of Fraser’s first US commercial gallery show in 13 years. The five works on view, from the late 1980s onward, get a new, retroactive reading from her current perspective of grappling with the complex, emotive terrain of racial privilege.

Fraser’s best-known performances offer pitch-perfect approximations of art speak and style, from staid guided tours to overblown acceptance speeches by egotistical artists, threaded with a feminist criticality toward gendered modes of presentation. Two major works from the 1990s, commissioned by the Wadsworth Atheneum and the São Paulo Bienal, …

January 20, 2023 – Review

Ali Eyal’s “In the Head’s Sunrise”

Dina Ramadan

“In the Head’s Sunrise”, a quiet yet compelling exhibition of Ali Eyal’s recent drawings and paintings, captures the intricacy and complexity of the young Iraqi artist’s practice; the emotional texture of the work, accomplished through rapid, forceful strokes, is immediately striking. Individually and collectively the works recreate moments from life in Eyal’s hometown—referred to only as small farm—where he came of age amidst the violent turmoil of the US-led invasion of Iraq. The titles of the pieces underscore Eyal’s propensity for narrative along with his acute awareness of its limitations; each enigmatic label ends with “and,” indicating its incompleteness, and suggesting that every encounter is a beginning, like tugging on a loose, seemingly extraneous thread that unexpectedly unravels the entire fabric.

Three heads walking between towns, and (2022) is the immediate focal point of the exhibition and reflects the mythological nature of Eyal’s work. The large canvas hangs like a banner, hands snatching at its sides, attempting to tear through the composition. Three women’s heads attached to makeshift bodies, an assemblage of ill-fitting and dislocated ligaments, dominate the canvas. They are reminiscent of the three fates, their thick black hair unfurling behind them like billows of smoke, each home to …

January 12, 2023 – Review

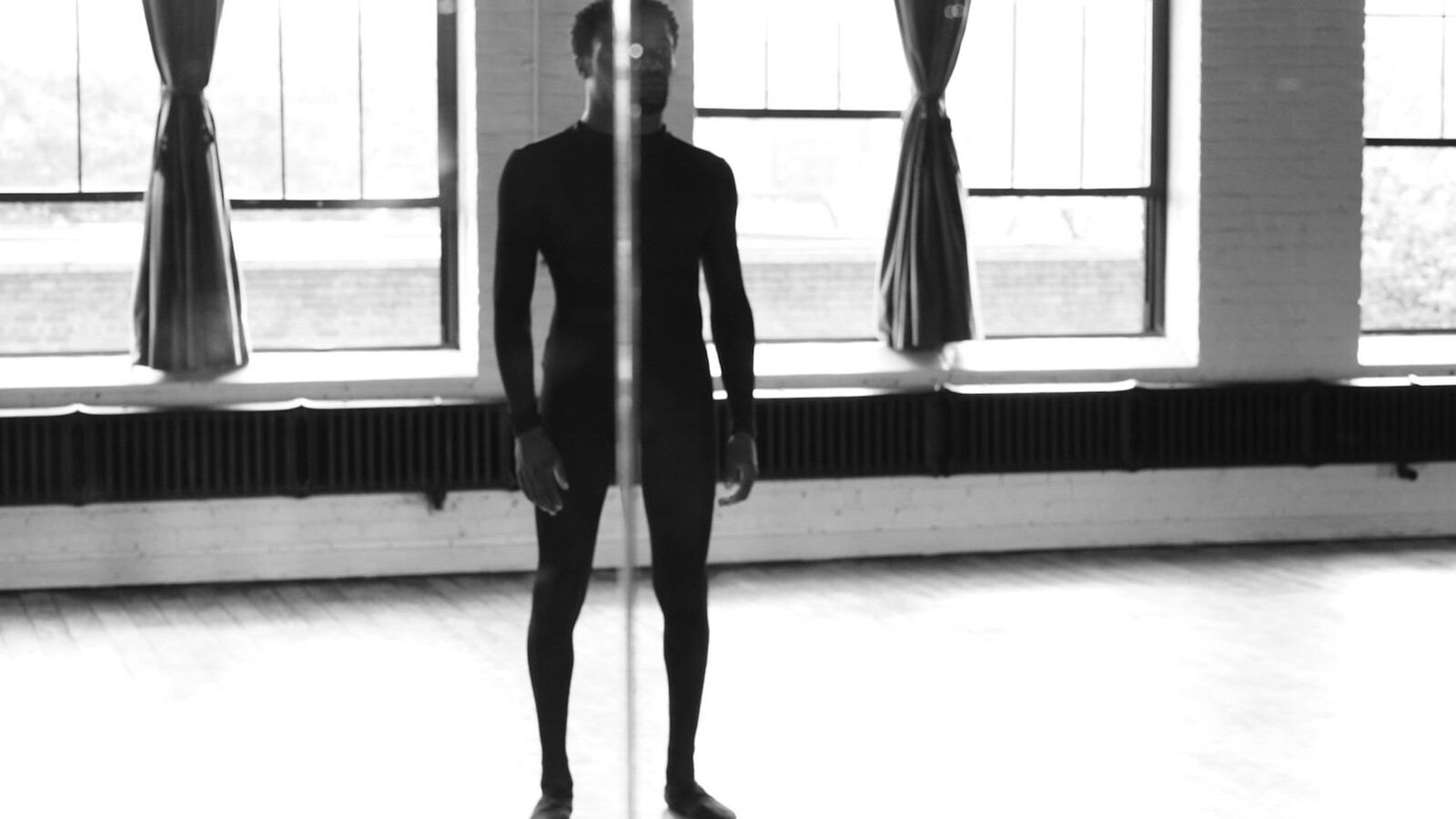

keyon gaskin with Zinzi Minott and Moya Michael

Rachel Valinsky

keyon gaskin, Zinzi Minott, and Moya Michael weren’t just stalling. Barely visible beneath their semi-opaque hooded cloaks, and positioned at various points around the entrance to Artists Space, they outlined the terms of their performance clearly: “Once we get moving feel free to roam around the space. We will be all over the place … We might get close to you … Keep your hands to yourself … Be mindful, be careful … We’re at work.” We “waited” for things to start—though, of course, they already had.

gaskin—an artist living in Portland, Oregon who performs both solo and in movement-based groups—has frequently made active audience engagement a feature of their pieces, eschewing passive consumption of black and queer performance by primarily white audiences. At the first performance commission held across Artists Space’s 8,000 square feet, audience-performer interactions were diffuse in part because of the building’s size—the performance took place over several rooms, and not all of it could be witnessed simultaneously. Visibility, its trappings and attendant politics, were not so much withheld as decentered. “We can’t see everything,” gaskin and their collaborators cautioned at the start, implying that neither should we. “Remember, this is a performance, but not your performance. …

December 6, 2022 – Review

Nikita Kadan’s “Victory over the Sun”

Xenia Benivolski

The 1913 opera Victory over the Sun describes an attempt to capture the sun in order to overthrow linear time and reason. The work ushered in artistic traditions that came to shape Soviet Futurism: it’s where Malevich’s black square, for instance, made its first appearance (on a set curtain). Nikita Kadan’s exhibition, which takes its title from the opera, is anchored by a wall-hanging neon sculpture entitled Private Sun (2022) which refers to a classic of Soviet-era design: a window grate, ubiquitous in large apartment buildings, with bars like the rising sun. Where the avant-garde original advocated for the destruction of the present to clear a path for the new, the Ukrainian artist’s use of the architectural feature suggests a darker notion: of being held captive in someone else’s idea of the future.

Hanging in the main space of the gallery is a series of charcoal drawings. In one, titled A Sun-headed character in a garbage bag (2022), Kadan renders a black trash bag akin to those rumored to have been used to transport the bodies of soldiers killed during Russia’s invasion. Over the trash bag presides an unsmiling black sun. In another, similar drawing (The Sun I, 2022), a black …

November 9, 2022 – Review

Jumana Manna’s “Break, Take, Erase, Tally”

Dina Ramadan

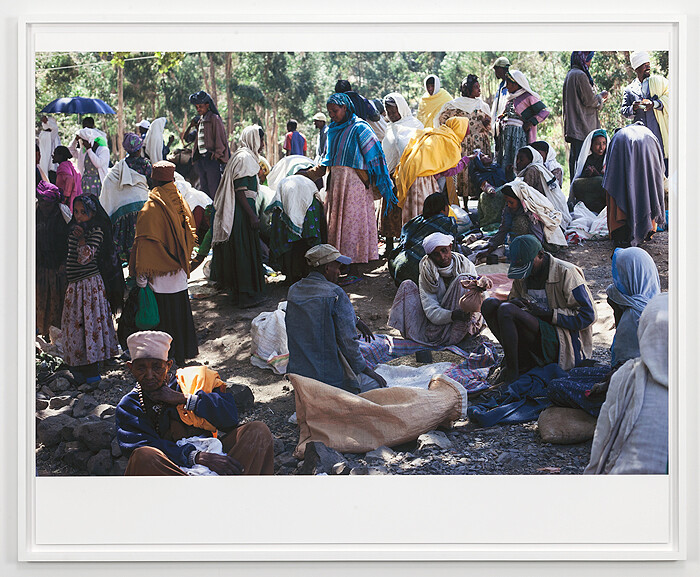

Jumana Manna’s first US museum exhibition traces the violence inflicted through infrastructures designed to control, transform, protect, or even destroy the natural environment, while recognizing the ways in which the land, in its mutations and transformations, resists in order to survive. Knowledge produced from and about the land emerges as a site of struggle, both an apparatus of hegemony and oppression and a potential tool for defiance and liberation.

The exhibition includes recent and newly commissioned sculptural works; pieces from the multidisciplinary Palestinian artist’s ongoing “Cache Series” populate the main gallery space. These large, smooth, earth-toned ceramic sculptures seem capable of shape-shifting despite their sturdiness. Inspired by the khabyas—the storage vessels attached to homes throughout the Levant that have been rendered superfluous with the proliferation of modern means of refrigeration—they capture these structures in various states of disintegration and ruination. Some share recognizable features of the original khabya while others have morphed into unfamiliar forms, alien-like creatures whose disfigurations speak to their incongruity in the contemporary landscape, glossy monuments to their own demise in the face of industrialized means of producing and conserving food.

Throughout the exhibition, Manna borrows from the visual and organizational language of archival institutions; the steel …

September 27, 2022 – Review

Ghislaine Leung’s “Balances”

Katherine C. M. Adams

What one sees of Ghislaine Leung’s “Balances” depends on precisely when one visits the exhibition. During Leung’s own “studio hours” (9 a.m. to 4 p.m., Thursday and Friday), Gates (2019) lines the main gallery space with child safety gates. The work’s three editions—each a different neutral shade—have been installed on top of each other: sometimes they occupy the same elevation of the wall in dense proximity, and at other points are stacked vertically. Directly before the first group of Gates is one half of Monitors (2022)—a baby monitor transmitting live footage of the gallery’s back office. Other works on view in the central space include Fountains (2022), a small readymade, three-tiered fountain burbling loud enough to “cancel sound” in the vicinity, as the work’s score instructs. A partly filled rectangular grid the size of Leung’s studio wall, Hours (2022), covers the largest wall.

Outside these hours, the gallery is apparently blank, all works removed or covered over. “Balances” exercises an unusually strict control over the terms of encounter with its work, calibrating the viewing situation to the artist’s allocated studio time for art production. In a correspondence with the gallery reproduced in the show’s press release, Leung explains the three-way …

September 23, 2022 – Review

“A Maze Zanine, Amaze Zaning, A-Mezzaning, Meza-9”

Rachel Valinsky

Pulling up to David Zwirner on the opening night of its tongue-twistingly-titled benefit show for Performance Space New York, the scene was chaotic: a several-hundred strong mix of fashion week, Armory week, and overdressed Chelsea partygoing crowds spilled out onto 19th Street, closed to car traffic and repurposed for a block party, complete with food stands and ice-cream truck. Inside, five long banners co-made by the exhibition’s all-star squad of artist-organizers—Ei Arakawa, Kerstin Brätsch, Nicole Eisenman, and Laura Owens—hung from a beam overhead.

These screen-printed, acrylic- and vinyl-painted Curtains (all works 2022 unless otherwise stated)—a title that evokes the fabric separating audience from proscenium stage—read like précis of each artist’s signature style: one shows a cartoonish Eisenman figure raising paint roller to wall, while Brätsch’s and Owens’s colorful, abstract geometries and pop-cultural influences infiltrate others. Two open, wooden structures on wheels evoked both stage props and domestic spaces (they are called “houses” on the gallery map). Behind the curtains, Performance Space’s metal rigging structure was temporarily relocated as décor, where it dynamically remodeled the gallery’s interior. A ramp leading to a platform wrapping around either side of the space served as the titular “mezzanine,” offering elevated views of the many paintings …

June 9, 2022 – Review

Anne Imhof’s “AVATAR”

R.H. Lossin

“AVATAR” is an installation featuring rows of industrial lockers, cored concrete blocks, a large, three-panel painting of clouds, figurative drawings, and new additions to Anne Imhof’s series of “Scratch Paintings”—large aluminum panels coated in custom automobile paint with patterns scratched into them by the artist. While no performance will be held here, it is impossible not to think of it as a set absent the actors—which, given the function of lockers and the potential density of bodies in a locker room, isn’t far-fetched, even if we bracket the German artist’s fame as a dramaturge. The lockers containing concrete blocks as a way of staging giant, slightly abstracted car doors is almost too literal if you have even a glancing, film-based familiarity with industrial production. The untitled cloud painting is compelling—beautiful in a Monet’s waterlilies sort of way. The drawings—mostly hung in a back space that functions as an office—are likely there so people have something to buy. The show is fine. Imhof is a talented painter and draughtswoman. One could leave it at that if it weren’t for the ghosts of bodies that might use the lockers on the way into a General Motors plant.

Imhof continues to describe herself …

May 17, 2022 – Review

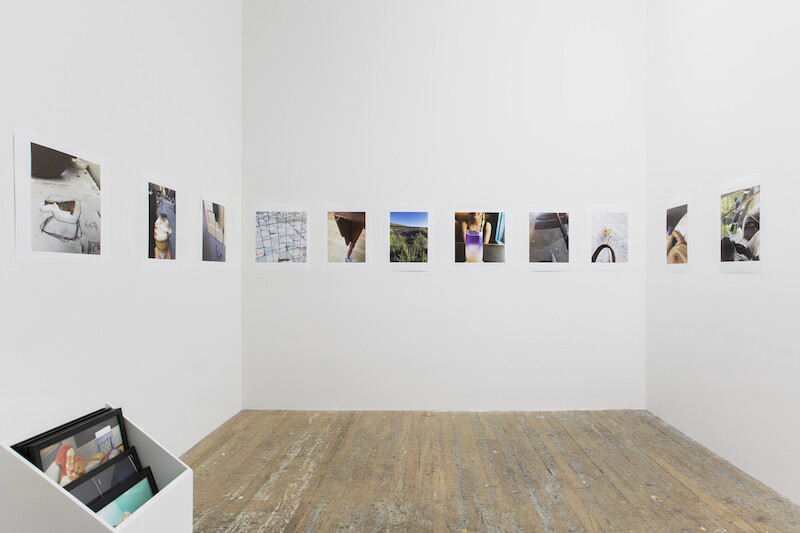

Josephine Pryde’s “Taylor Swift’s ‘Lover’ & the Gastric Flu”

Travis Diehl

Josephine Pryde’s campily titled show at Reena Spaulings frames the genius of Taylor Swift—her capacity for reinvention and the influence of her confessional songwriting—as a model of the creative process. The story goes that sometime in 2019, Pryde, an English artist known for detourning the conventions of commercial photography, came down with a stomach bug: she spent her convalescence listening repeatedly to Swift’s album Lover, released that same year. In the months since, she produced a series of twelve bronzes by chewing on a piece of gum while remembering a different track, matching her chews to the rhythm of each song in a kind of masticatory lip-sync. She stuck each resulting wad to one of the pieces of driftwood or small rocks scattered around her flat, cast the assemblages in bronze, and patinated the gum part a scaly green. Hannah Wilke, eat your heart out.

Pryde’s goal seems not to relive or remember her illness so much as transpose it into the key of Taylor’s heartbreak. Each piece is titled after the song in Pryde’s head while she made it: “The Archer”; “Paper Rings”; “Miss Americana & The Heartbreak Prince.” The suggestion is that the tenor of each song affected …

May 13, 2022 – Review

Em Rooney’s “Entrance of Butterfly”

R.H. Lossin

“Entrance of Butterfly,” Em Rooney’s third solo show with Derosia (formerly Bodega), consists of six large sculptures and the looping, 11-minute slide show that gives the exhibition its title. The artist has previously integrated photographs into her sculptures, but here the 80 color stills are disaggregated and projected at a notably small scale in a separate gallery: their relation to the sculptural forms is symbolic or narrative rather than material. If these representational images suggest context or content for their more abstract, three-dimensional counterparts, it is only in the most provisional way. The wall-mounted sculptures, titled with reference to films and natural processes, have a descriptive power of their own.

trouble every day (all works 2022) is the approximate size and shape of a headless dress mannequin. Impaled on the steel strip that secures it to the wall, the candy-wrapper quality bestowed by Mylar and coated rice paper is at odds with the violence of a disarticulated female torso. This shape, at once a replica and an encasement of the female body—shiny, blue, aggressively corseted by sharp, rhinestone-studded petals (synthetic whale boning and all)—invites us to dwell on the often incompatible demands made on women’s bodies (literally, materially on them). …

April 28, 2022 – Review

Elbert Joseph Perez’s “Just Living the Dream”

Hallie Ayres

A pristine, nondescript hammer dangles upside down from the skylight in Rachel Uffner’s upstairs gallery. Situated on a pedestal directly underneath are three porcelain figurines: a swan, a lamb, and a pony. Arranged in a congregation that is as tender as it is eerie, the figurines exude a fragility that is exacerbated tenfold by the hammer’s precarious installation. The notion that moments of suspension—of disbelief or otherwise—can so quickly turn catastrophic runs through the rest of the works on display in “Just Living the Dream,” Elbert Joseph Perez’s first solo gallery show in New York City.

The motif of ceramic figurines of baby animals on the brink of violent extermination recurs throughout Perez’s suite of paintings. The eleven compositions, all oil on canvas, oscillate stylistically between aesthetics of naturalist still life and symbolist metaphysics. Their conventional orientation on the gallery wall belies the foreboding subject matter. Duhkha Aisle (all works 2022) features a ceramic duck in a cowboy hat, an immobile target for the rearing snake in the hellscape behind it, while 16 oz. Migraine positions the glazed upper body of a horse inches away from a glimmering sledgehammer affixed to something beyond the bounds of the canvas by a …

April 5, 2022 – Review

80th Whitney Biennial, “Quiet as It’s Kept”

Dina Ramadan

In her 1988 lecture, “Unspeakable Things Unspoken: The Afro-American Presence in American Literature,” Toni Morrison explained that the opening sentence of her 1970 novel The Bluest Eye—“Quiet as it’s kept”—was a familiar idiom from her childhood, usually whispered by Black women exchanging gossip, signaling a confidence shared. “The conspiracy is both held and withheld, exposed and sustained,” Morrison tells us. By borrowing this expression for the 80th edition of the Whitney Biennial, curators David Breslin and Adrienne Edwards promise the intimacy of knowledge bestowed, an exploration of the tantalizing space between hidden and revealed, a quiet reflection on whispered truths.