The past decade has seen a shift in art’s center/periphery model, as so-called “Outsider Art” gains both curatorial and market visibility. Yet far from losing its particularity, as David Maclagan notes in a 2012 frieze roundtable, Outsider Art risks becoming “a prospective concept, continually enlarging itself, not least because of the commercial pressures driving it.”1 The term, in other words, may remain an expedient, ignoring the wildly different interests and circumstances of the artists in question.

One of the roundtable discussants was Paul Laffoley, a Boston-based artist who sometimes falls into this category, though prefers to describe his relationship to the art world as that of a “lightly touching tangent.”2 While Laffoley has a few of the stereotypical qualities of the Outsider—an intensely private studio practice, a spiritualized singular vision—his commitments to theology and philosophy are too vast and scholarly for easy categorization.

This partly owes to his upbringing. Laffoley’s father, a lawyer, cultivated an interest in occultism and Eastern faith practices (supposedly performing as a medium). When diagnosed with mild Asperger’s Syndrome, the artist found himself in the tutelage of an Indian Brahmin who taught math at Harvard. That said, Laffoley’s creativity might also derive from a more unusual muse: a small implant discovered, in 1992, during a routine CAT scan of his brain. After consultation with a local chapter of the Mutual UFO Network, he concluded that “the implant is extraterrestrial in origin and is the main motivation of my ideas and theories.”3

“The Force Structure of the Mystical Experience,” currently on view at Kent Fine Art, New York, is a retrospective-scale treatise of Laffoley’s thought. Its paintings, sculptures, and drawings—many shown here for the first time—date from 1962 to 2013, though one can scarcely tell the decades apart. The artist cuts wild lines through philosophies and belief systems (Neoplatonism, Kabbalah, Theosophy, etc.) with a consistency that belies chronological time but plays to his advantage on the market. Laffoley may consider himself a “tangent,” but he nonetheless benefits from the paradoxical valuation of Outsider Art. To wit: he’s prized precisely for being at odds with the logic and temporality of the art world.

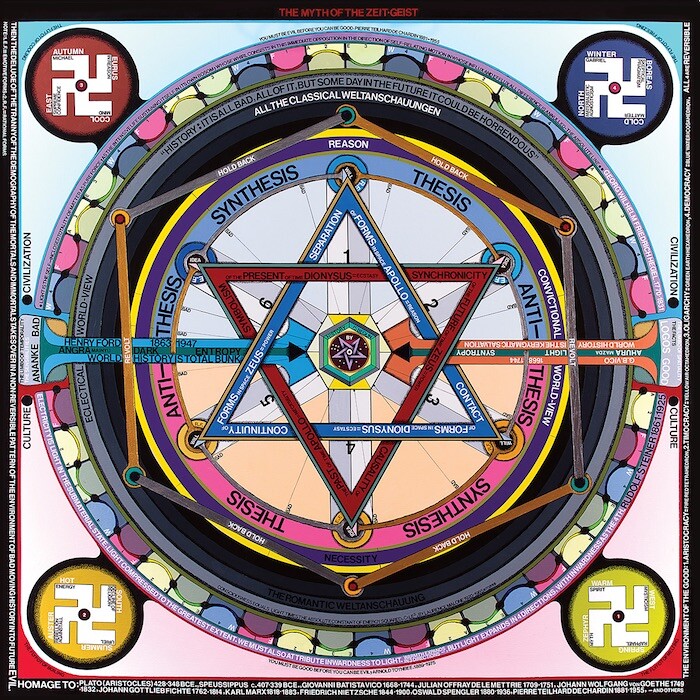

Laffoley is best known for his square, mandala-like paintings, systematically organized by blocks of vinyl lettering. A characteristic piece, The Myth of the Zeitgeist (2013), departs from the contention that evil is the source of history, powering a temporal dialectic in three repeating world cycles. Ostensibly, Laffoley’s painting takes on an ambitious representational task, with the swastika, hexagram, and pentagram providing symbolic support. In fact, it may be closer to a schematic; the artist has remarked that the elements of his work are not symbols but “entities,” which, under the right viewing conditions, can “manifest.”4 The nature of these conditions is unclear. Laffoley’s work demands too much from those seeking a spiritual quick-fix—and, he notes, some of his collectors have needed as many as fifteen years to even begin comprehending their purchases.5

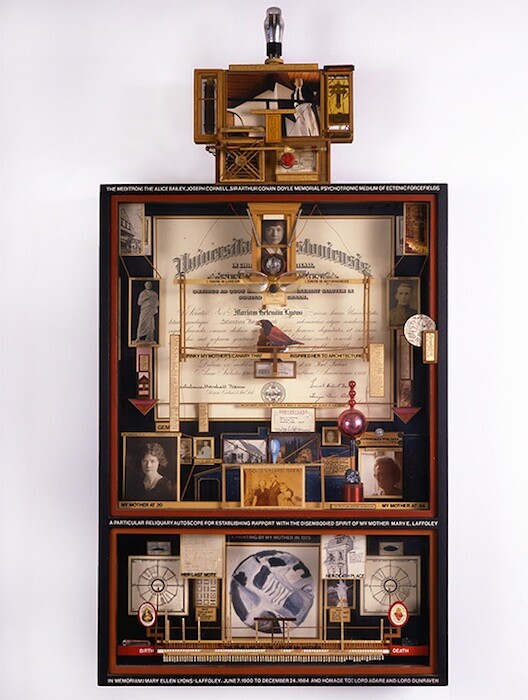

The most poignant work in the exhibition is The Meditron (1985), a psychic device that allows Lafolley and loved ones to communicate with the spirit of his mother, who passed away the previous year. With an explicit nod to Joseph Cornell, this shadow box contains innumerable contents, from his mother’s birth certificate and spectacles to a small timeline, made of wooden sticks, marking the significant moments of her life. A copper wire runs throughout the box and connects to a crystal set, comprising one of the device’s mechanisms. Another mechanism, a vinyl text states, is “stronger than death”: “There is love or there is nothingness.” Laffoley has communicated with other spirits (most famously Nikola Tesla), but this piece makes the most emphatic claim for reaching beyond the physical realm.

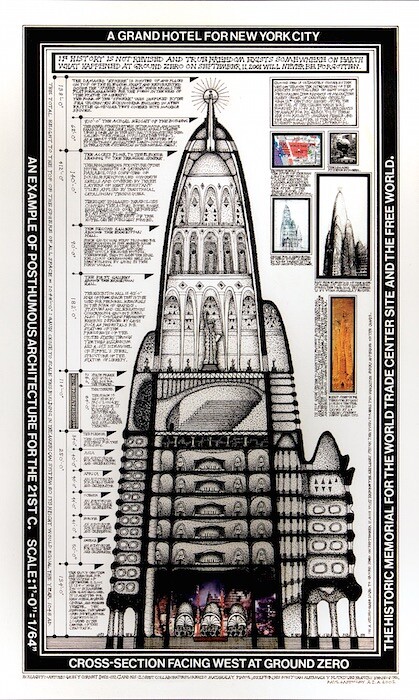

At moments in his life, Laffoley has brushed up against architecture: in a stint as a student at Harvard, during an apprenticeship for Frederick Kiesler, and as a drafter of the floor plans for the World Trade Center. Several maquettes on view at Kent Fine Art bear testament to the artist’s ongoing interest in the field. Das Urpflanze Haus (Model) [The Archetypal House] (1981-97), for example, offers a housing solution for the swelling global population. Taking its name from an archetypal plant, which Goethe imagined as the source of all vegetal life, Laffoley proposes splicing genes of Ginkgo biloba with those of other plants, towards the creation of botanical dwellings. In a sense, this aspiration is currently taking form, as architects like David Benjamin and Ginger Krieg Dosier explore innovative building techniques with mushrooms, sand, and bacteria. Laffoley’s prescience about living architecture, in short, begs consideration that some of his many other visions may also come to pass.

Jonathan Griffin, “Frames of Reference,” frieze no 150 (October 2012), http://www.frieze.com/issue/article/frames-of-reference/.

Ibid.

Paul Laffoley, “Disco Volante,” Official Paul Laffoley Website (1998), http://paullaffoley.net/writings-2/disco-volante/.

Phil Weaver, “Paul Laffoley’s Alchemy: The Telenomic Process of the Universe” (2013), http://www.imperiumpictures.com/portfolio-item/paul-laffoleys-alchemy-the-telenomic-process-of-the-universe/.

Rupert Howe, “Paul Laffoley,” Wonderland (September 24, 2009), http://www.wonderlandmagazine.com/2009/09/paul-laffoley/.