Ever-regenerating discussions in mainstream documentary discourse pit form in opposition to function. It is still commonly understood that utility and representable actuality risk becoming diluted or confused by formal invention or experimentation with narrative structure. This reasoning foregrounds a perpetuating valuation in the inherent power of the documentary as a pedagogical and propaganda tool, above all else, and suggests that a kind of ideal documentary purity is always just out of reach. Consequently, this has also produced infertile grounds from which to begin discussing documentary works that sit outside of documentary convention, even after a particularly fruitful past decade of aesthetic development in the discipline.

In some sense, the documentary’s entrance into the art world as an aesthetic and as a research mode has helped to lessen this specific pressure on the form (whether that pressure is justified is another matter). The expanded material exhibition practices of contemporary art help to constellate a more coherent message—of evidence, explanation, context—that would otherwise need to emanate solely from the single work, thereby leaving it more often than not suffused in and defined by didacticism. At the same time, contemporary art does not typically require such a rigorous self-justification in terms of its usefulness. Utility, for an artwork, is rather a slippery and incidental value.

Rosalind Nashashibi makes films for exhibition in the gallery. Her works operate in terms of observation and visual comparison, and blend the captured with the constructed. In its installation, her film and video work often expands beyond the cinematic space, with additional stills, objects, and text. In her current show at Murray Guy, “Two Tribes,” Nashashibi pairs experimental documentary filmmaking with her own hintingly figurative abstract paintings. This combination leads to another kind of didacticism for the exhibitionary space: the works come together not to explain what to know or take away, but how to look, or what to look for, in the other.

Nashashibi’s single-channel, 17-minute film Electrical Gaza (2015) plays on a loop in the gallery’s back room. Originally commissioned by the Imperial War Museum in London, the film documents a journey to Gaza in 2014 (after years of attempts to cross the closed border on the part of the artist, of mixed Irish and Palestinian heritage, and her small team) on the eve of Israel’s protracted bombardment, officially known as “Operation Protective Edge.” The resulting work is an impressionistic depiction of routine life in Gaza, accented by a score that mixes and intersperses field recording and ambient electronic and classical music, at times followed by jolting transitions into silence. These punctuations are straightforward and prominent compared to the cyclical visual editing. Sometimes similar scenes repeat themselves, like a memorable view of boys washing their horses in the sea, while others play best for effect once, such as a scene of men in a living room singing songs. Scenes of the noisy and desperate chaos of the border recur throughout. While hanging mostly at street-level, at times the view suddenly pans above the city, surveying it (or surveilling it). Pulling at the other end of the camera’s observational authority, some scenes transform into animations. This augments the images’ painterly quality, and gives a different, more maudlin feeling to the filmed scenes: the animations act as incursions on the authority of the image, and overlay an “unreal” sensory view over the camera eye, both complicating and overstating the original. In another intervention into the filmed image, a black hole expands into its space, resembling the “black moon” of cinematic processing, and an omen of the coming bombardments.

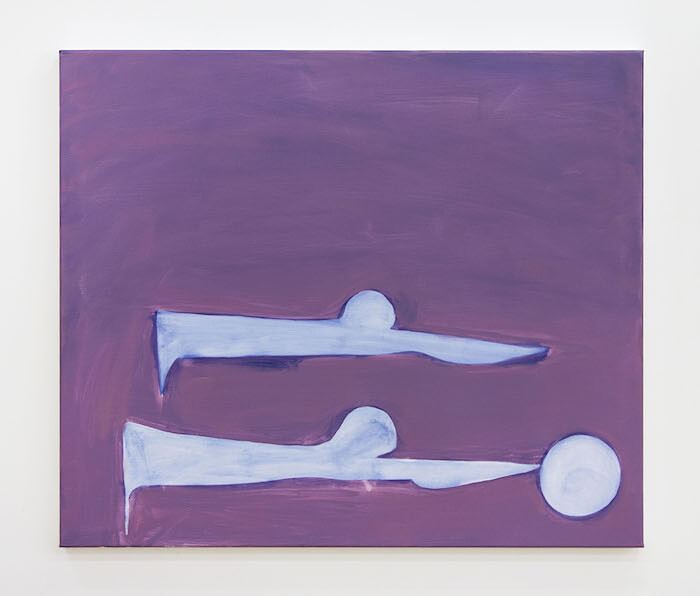

The other rooms of the gallery present a series of several new paintings by the artist. These works feature soft-edged forms that sometimes indicate bodily positions or objects at rest, while others are more deeply abstracted, suggesting, if anything, molecular forms or cells in motion. In one oil painting, titled Love and Violence (2016), two lightly blued parallel figures cut through a twilight horizon like a pair of swimmers in unison. A series of large gouache-on-paper works—X, and two works each titled The Hanging (all 2016)—depict cavities of animistic blobs. Regarding these, the attendant press release reads almost as a set of instructions, noting that paintings ”have a potential to disrupt focus and change the way in which the film is experienced, loosening its attachment to narrative or documentary.” Taking this cue, it does indeed become possible to project depictions from the film in the paintings and then go back to the film to inspect its formal plays and its color compositions over its social content. But what is this after, and what does it serve?

Are these paintings necessary to make the film seem more like an art thing, acting as a certified cover for the documentary work? Or is this a little dig to New York contemporary art audiences, in which the gallery-goers require the formal notes of the documentary to be explicated, so here are these handy paintings as a key to the art in the media? In either case, this pairing identifies respective weaknesses in documentary and contemporary art discourse as well as an intrinsic inability for either to communicate productively with the other. And in that case, the disturbance is a welcome one.