While Charles Baudelaire’s definition of “the ephemeral, the fugitive, and the contingent” is a familiar truism of contemporary understandings of “the modern,” Baudelaire’s casual, even offhand 1863 observation, “nature, being none other than the voice of our own self-interest,” is less well known. Yet if one were to draw a line from Baudelaire’s nineteenth-century evocation of the early days of modernism to our twenty-first century epoch of over-modernism(s), who but the artist Mark Dion would affirm Baudelaire’s prescient observation? As Dion knows, and explores once again in his exhibition “The Library for the Birds of New York and Other Marvels,” we live in an era when this self-interest has cast the very planet we live on into a melancholy condition of the “ephemeral,” “fugitive,” and “contingent.”

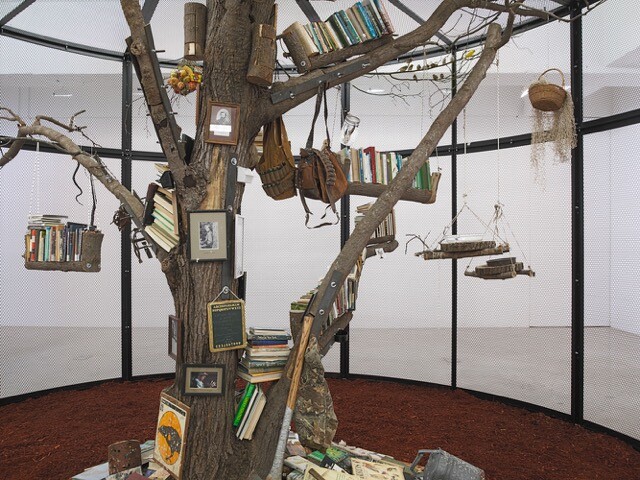

While a quick impression of the works on view suggests Dion has broken no new ground, and may even be recycling what have become all-too familiar tropes, it is the contingent, the detail, the specificity of the subject matter of each piece, that reveals once again Dion’s cogent, nuanced, and up-to-the-minute dissection of this self-interest we call nature. For instance, the formal elements (monumental bird cage, dead tree trunk, shelves and piles of books, photographs of iconic figures, paraphernalia from the study of nature-culture, and 18 live zebra finches and 4 yellow canaries) of the large immersive atrium The Library for the Birds of New York (2016) look much like what one sees in photographs of Dion’s 1993 installation The Library for the Birds of Antwerp. But context and historical juncture is key to both. The Library for the Birds of Antwerp referenced art history, birds and painting, and colonial aspects of owning birds, parrots in particular, as symbols of stability after the Thirty Years’ War, while The Library for the Birds of New York juxtaposes images and books of progressive nature conservationists with the study and culture of science (there is a well nibbled chemistry textbook in the bird poop-covered pile at the base of the tree). These themes are contrasted with references to the persecution of birds by hunting and study of them (the zebra finch is the laboratory corollary of the white lab mouse; the canary is the obvious metaphor in the coal mine), but also through our devotion to the domestic house cat—a copy of Catwatching and Catlore, Desmond Morris’s 1986 book on cats, peeks out from the pile of books. Nonetheless, the wonder, pathos, and humor of hanging out in a transient home for these robust and clearly delighted avian constructs of human research and signifiers of mortal toxicity is a blast.

Continuing the exhibition’s interest in nature as pop and play, The Phantom Museum (Wonder Workshop) (2015), a collection of neo-1970s glow-in-the-dark chartreuse 3D sculptures based on seventeenth-century engravings (and made with students from Colgate University), are displayed in their own room as though in a horror-house natural history museum. Among them is the famous nineteenth-century multi-headed Hydra of Hamburg about whom it fell upon Carl Linnaeus, on his visit to the city, to remark, “You are aware it is a fake?,” crushing the imaginations of child and adult alike. While Phantom Museum is good-natured and whimsical, An Archeology of Disorder (2016)—a trophy or specimen case complete with shelves of crowded dusty objects and emblems of mental affliction—explores the exhibition’s interest in the darker, indeed sinister side, of natural history’s constructions of the normal and the pathological. Forming a kind of essay of objects, An Archeology of Disorder is as serious and studied as an essay by Foucault.

Of all the works in the show, Cabinet of Marine Debris (2014) is the piece most in need of background, as the magnitude of what is on display is easy to miss. Marine-themed objects, displayed in familiar natural history museum cabinet format, attest to Dion’s self-described role as disaster-chronicler because they are selected from tons—yes, tons—of garbage Dion collected while part of an expedition of researchers, material scientists, and artists (sponsored by the Smithsonian, National Geographic, and the Alaska Wildlife Federation, a foundation founded with the settlement money from the far from transient 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill). As with The Library for the Birds of Antwerp, it is not the formal construction of the piece (unless one is seeing Dion’s work for the first time) so much as the significant horror of the subject matter that sticks in one’s gut, like the ubiquitous plastic bags we now find twisted inside birds. For these bottle caps, arranged by color, from as far away as Japan, China, and India, plastic buoys from Japanese squid fishing nets, barnacle-covered light bulb, rubber gloves, and tools are merely a tiny selection of the knee-deep garbage thrown daily onto these remote Alaskan shores by the gargantuan Pacific Gyre (also known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch).

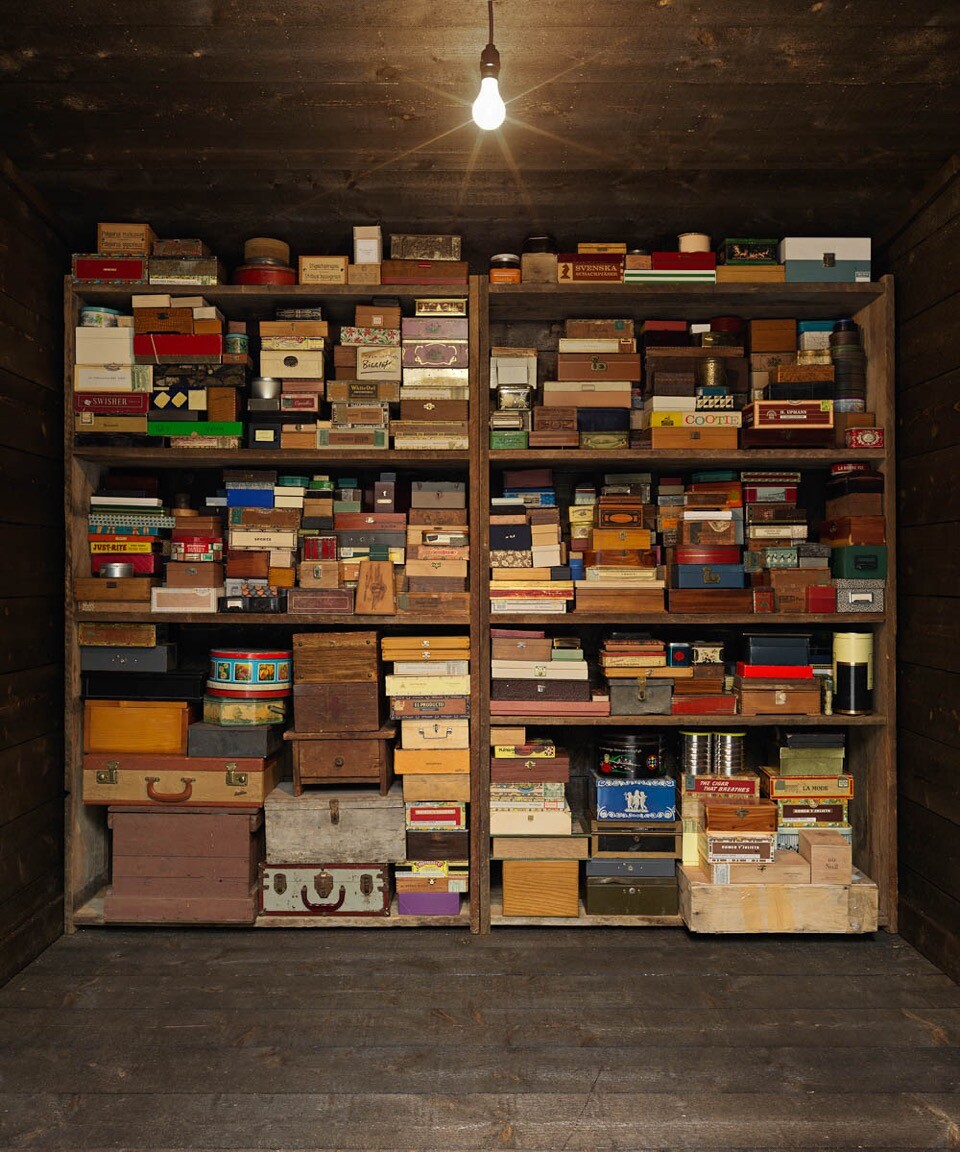

Memory Box (2016) takes the theme of the castaway, the lost object, and the remainder back into a more colloquial, even personal, evocation of the obsessiveness of collecting. In fact, this ramshackle shack, reminiscent of the structures found at Dion’s and J. Morgan Puett’s living artist’s colony Mildred’s Lane, in rural Pennsylvania, rivals The Library for the Birds of New York for the interactive, immersive pleasure with which it engages the viewer. After one enters by stepping up and into its dark interior, one is confronted with hundreds of variously sized and functioning beat-up metal, silver-plated, cardboard, wood, even velvet boxes and drawers. These ungainly piles, as if discovered in a dead uncle’s attic, line the wall from floor to ceiling with mystery and obsession. Each contains some oddity Dion has collected over decades of expeditions to flea markets, thrift shops, and rural yard sales. What makes it so enjoyable is also what makes it so quietly subversive: visitors are given full freedom to open and fondle, break and steal (although that was not the artist’s intent) anything—from a set of wish bones placed in an old silverware box (“one of my favorites,” he says), to a miniature metal reindeer sculpture, or tiny nineteenth-century ivory double-edged comb for combing lice from one’s hair, old board games, and even actual fauna (a centipede). When asked whether it bothered him that things might be stolen, or even broken and mutilated, Dion responded with pointed emphasis, “The wear and tear is definitely part of it. I mean, isn’t that the whole point? These ideas we have about art are not natural so we need to push back.”