Robert Smithson grew up collecting rocks, shells, and insects. He adored The American Museum of Natural History, about which he famously said: “There is nothing ‘natural’ about the Museum of Natural History. ‘Nature’ is simply another eighteenth- and nineteenth-century fiction.”1 An iconic figure in what we now know as “Land Art” or “Earthworks,” he is best known for the conceptually radical distinction between site and non-site and the brilliant aesthetic repurposing of natural history, industrial decay, geology, cartography, photography (“art that is made out of casting a glance”[2]), entropy, erosion, gravity, the monumental, and the crystalline into tools and methods of conceptual and minimal art. Such works as Asphalt Rundown (1969), Spiral Jetty (1970), Partially Buried Woodshed (1970), and Floating Island to Travel Around Manhattan (conceived in 1970 but realized some 30 years after his death by Minetta Brook in collaboration with the Whitney in 2005), have given him an ambiance of neutral colors and earthy hues, tones drawn from the layers of geological sedimentation and industrial waste from which he made his art.

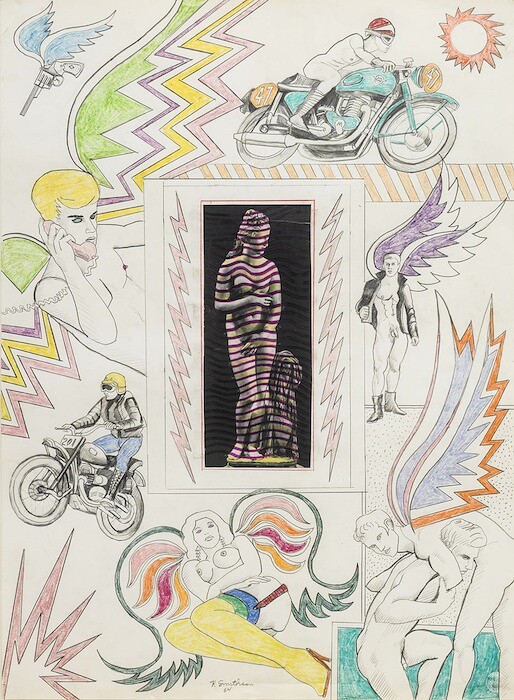

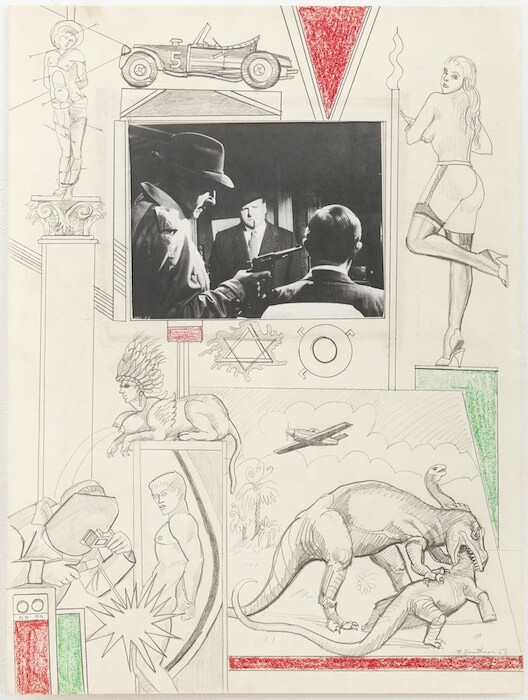

For this reason, you wouldn’t be the only one who passed through the glass doors of James Cohan’s handsome new gallery on the Lower East Side and wondered if someone had pumped laughing gas into your brain. “These are not by Robert Smithson,” was a remark overheard amidst the eye-popping psychedelic colors of Smithson’s “works on paper and sculptures” from 1962 to ’64, “I just refuse to believe it.” Not even the exhibition’s title, “Pop,” prepares one for the shocking psychedelic hues of burning chartreuse, hippie lavender, electric orange, lemon citrine, and bold aquamarine. One stands in marvel, taking in these rarely seen (although previously exhibited in various Smithson retrospectives) drawings, collages, and sculptures that offer little hint of Gravel Mirror with Cracks and Dust (1966), Nonsite—Essen Soil and Mirrors, or Mirror With Crushed Shells (both 1969).

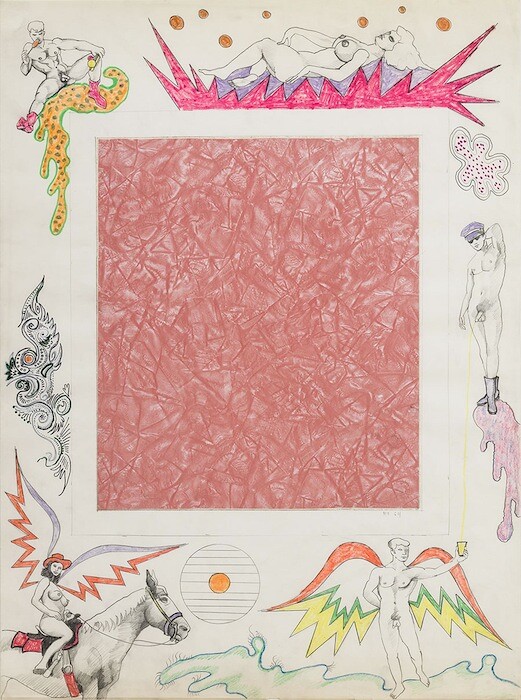

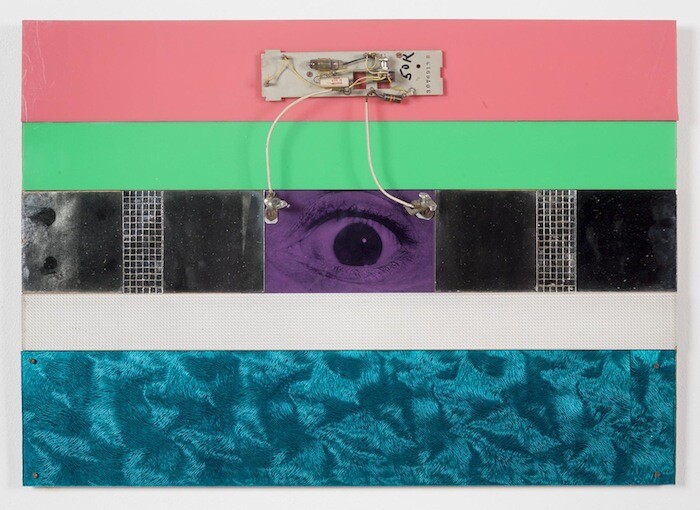

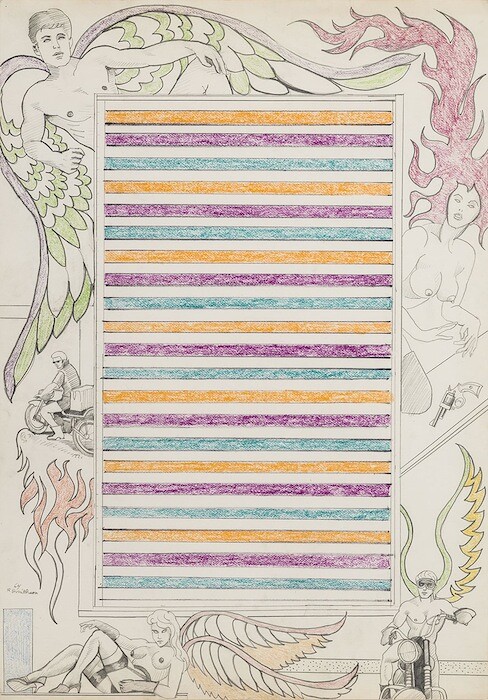

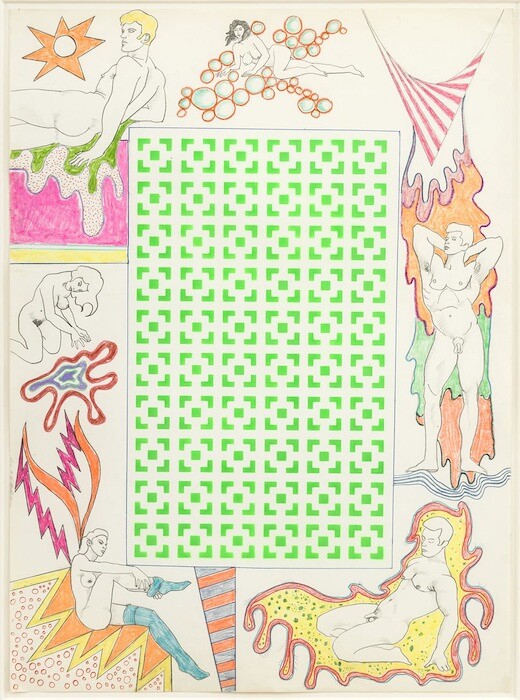

Take Untitled [Pink linoleum center] (1964), a hot pink, mottled-patterned laminate floor tile that sits proudly in the center of a 30 x 22 inch piece of paper, like a religious icon or illuminated manuscript, surrounded on all four sides by pencil drawings of winged big busted women, one on horseback, the other supine upon a psychedelic pink jagged lightning bolt. Archetypal homoerotic beefcake nudes expose their genitals proudly, one in classical contrapposto dressed only in biker boots and leather cap, another in hot pink booties, as he sits spread-eagled, penis and testicles prominently displayed, sucking on popsicles that appear to be made with the most toxic neon food coloring imaginable. The floating homoerotic gods produce a chuckle because they do not hang in the air on fluffy white clouds but rest on comic book renditions of dollops of dripping paint, sketched with pink and orange pencil. Out with the abstract expressionist drip and in with the blobby puddles of tears familiar from Roy Lichtenstein’s Drowning Girl (1963), derived from DC comic illustrator Tony Abruzzo’s “Run for Love!” (Secret Hearts no. 83, November 1962). In Untitled [Pencil write “less work for mother”/telephone cord spells “hello”/man on orange blob] (1963), the divine central image is a Day-Glo citron Op Art vertical square maze, while in Untitled [motel text] (1963) an abstract swirl made of chartreuse lava lamp-like blips outlined in pink fills the center, surrounded by more kitschy porno putti traced from underground pornography, popular male physique pictorials, and nudist magazines.

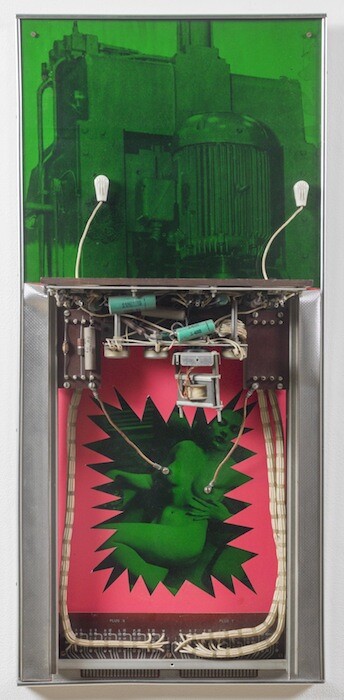

Although the show title orients us to Pop Art, the sensibility of these works is better appreciated by leaving such art historical categories in one’s back pocket, available for reference but not explanation. Imagine instead the young man as a mad modernist scientist-engineer constructing garish sci-fi contraptions (“sculptures”) such as The Machine Taking A Wife (1964) out of a girly pin up nude placed under magenta and green fields of Plexiglas, amplified with an actual rectifier tube,2 or Honeymoon Machine (1964) where the nipples of the mechanical bride are hooked up to electric circuitry. But the gut laugh of it all is Untitled [Record player] (1962)—an open record player that is at once a poor man’s Christian altar and kitsch Joseph Cornell box. An ornate pink and metallic plastic crucifixion, glued to the inside of the open lid, is surrounded by black-and-white photographs of celebrities—Warren Beatty, Ann-Margret, Annette Funicello, Elvis Presley—cut out of fan magazines, and plastic flowers. The “record” on the turntable is a white, pink, and green disk made of swirling streams of paint, propped on hay like an Easter Egg, topped with miniature rubber toy ducks.

Here is “solid state hilarity” avant la lettre. The phrase appears in Smithson’s first published essay—“Entropy and the New Monuments”3—in which he sets out to define the new monumentality he finds in the sculpture of his peers Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, and the fourth dimensional explorations of the Park Place Group. Riffing on Buckminster Fuller’s notion that for scientists the fourth dimension is “ha-ha,” Smithson founds a theory of “Generalized Laughter” based on linking six crystal systems with a taxonomy of laughter: “the ordinary laugh is cubic or square (Isometric), the chuckle is a triangle or pyramid (Tetragonal), the giggle is a hexagon or rhomboid (Hexagonal), the titter is prismatic (Orthorhombic), the snicker is oblique (Monoclinic), the guffaw is asymmetric (Triclinic).”

Regardless of whether one chuckles, giggles, titter, snickers, or guffaws, it is clear that “Pop” directs us to a material rarely associated with Smithson. As he puts it, “From here on in, we must not think of Laughter as a laughing matter, but rather as the ‘matter-of-laughs.’” “Pop” is a welcome initiation into Smithson’s delight with “the entropic verbalization” of just such matter.

Quoted on the first page of Jack Flam’s “Introduction: Reading Robert Smithson” in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, edited by Jack Flam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), xiii.

Rectifier tubes transform voltage from AC to DC which one is inclined to associate with DC as in comics.

“Entropy and The New Monuments,” (first published in the June 1966 issue of Artforum) in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, 21-22, in which Smithson also writes that “The order and disorder of the fourth dimension could be set between laughter and crystal as a device for unlimited speculation” and that “Laughter is in a sense a kind of entropic ‘verbalization.’”