Archival documents “are not items of a completed past, but rather active elements of a present,” writes Ariella Azoulay. As e-flux Criticism takes a break from publishing new material in August, the editors have selected a few pieces from our free-to-access archive (of more than 1,700 articles) that might relate in new and unexpected ways to the moment.

Matthew Barney’s recent show at Gladstone Gallery explored the limits of the body by pushing the boundaries of his materials. Thyrza Nichols Goodeve’s response to his 2016 show at the same venue—which “mirrors but does not reproduce” the 1991 show that transformed Barney’s reputation—offers a nuanced overview of a career characterized by continual reinvention that comes from repeated return to a creative source. Barney’s new video installation SECONDARY is on view at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in Paris through September 8.

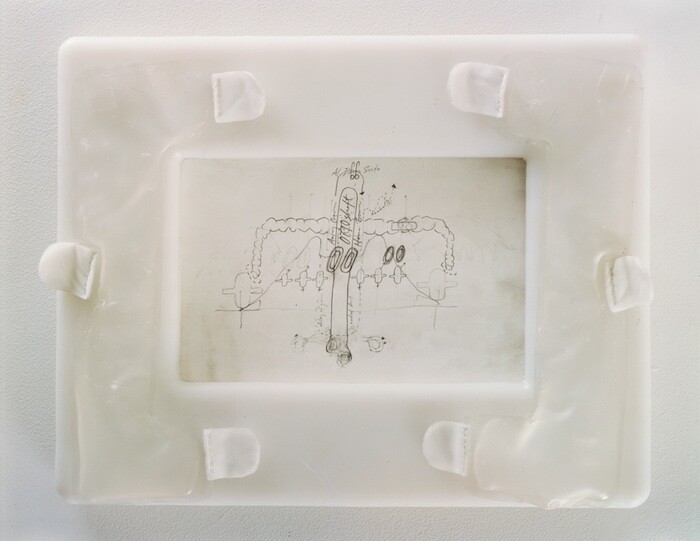

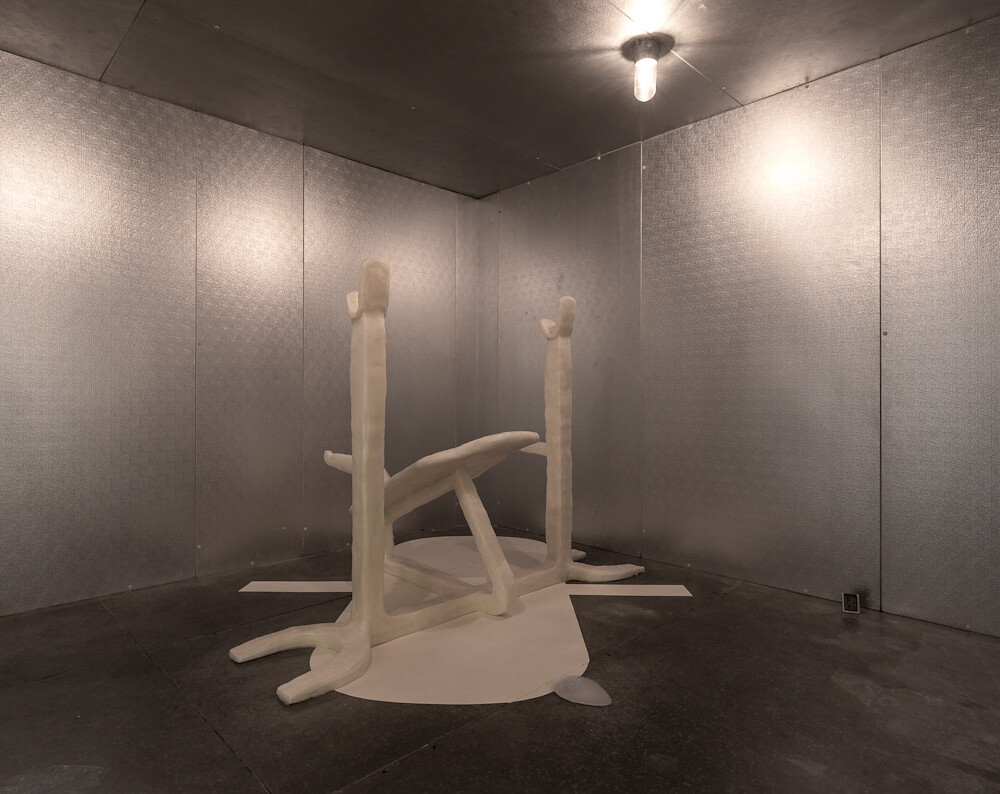

“Facility of DECLINE” at Gladstone Gallery, New York, “mirrors but does not reproduce” Matthew Barney’s iconic 1991 exhibition of the same name at the gallery’s SoHo space.1 Immediately upon entering, one is immersed in Barney’s now familiar yet ever fantastic world of petroleum jelly, mythic characters, seductive hermeticism, and ever-revelatory aesthetic invention: the signature hermetic conceptual drawings in self-lubricating plastic frames and petroleum jelly (rendered in graphite with that gorgeous, light, sinuous, even awkward Old Master hand); Caucasian flesh and bright yellow wrestling mats; football and weightlifting paraphernalia; speculums; cast sucrose capsules and barbells; saltwater pearls; an NFL jersey numbered “00”; thermal retractors, red skeets, binding belts, a hydraulic jack with glucose syrup; a “hubris pill”; various electronic freezing devices; numerous references to Oakland Raiders football star Jim Otto; Harry Houdini, dubbed “the Character of Positive Restraint”; and the melancholy intersex diva TRANSEXUALIS (1991), a weightlifting bench cast in petroleum jelly and enclosed in a walk-in-cooler.

Twenty-five years after its first exhibition this critical early work—which transformed Barney from a recently graduated pre-medical student into one of the most astonishing and influential artists of the 1990s—is not only alive and well, but finally has its moment. What was ungraspable, eccentric, and misread in 1991 as merely a rehashing of 1970s performance art via white male hetero/homosexual privilege is, as Maggie Nelson argues, of a body and desire that “has no gender; it is neither male nor female, neither human nor animal, neither animated nor inanimate. Its orientation emphasizes neither the feminine nor the masculine and creates no boundary between heterosexuality and homosexuality or between object and subject (…) It favors no organ over any other, so that the penis possesses no more orgasmic force than the vagina, the eye, or the toe.”2

The re-staging of Barney’s ’90s debut coincides with a general interest in foundational exhibitions from the era, such as “The Nineties,” a section curated by Nicolas Trembley at this year’s edition of Frieze London. Returning to groundbreaking exhibitions, not just works, reminds us of the profound ontological transformations of art and objecthood that occurred at this time. In a way the generative effects of trauma (such as Barney’s interest in hypertrophy or the death of Houdini by a punch to his abdomen) were not only a major theme of this period but remain its essential presence in the narrative of contemporary art history.

Barney’s work, as this lag in understanding implies, is not easy. It does not truck with resolutions and wholes but demands attention, synthetic analysis, time, and most of all sensitivity to materials. Storytelling is one of his most inventive forms, and each of his stories is rooted in the associative and formal potential of physical materials. REPRESSIA (1991)—a (white-)flesh-colored wrestling mat with a wound held open as in a surgical operation by a sternal extractor, oozing a life-fluid of petroleum jelly that slides over a pair of twin testicular red skeets, while a cast petroleum-wax and petroleum-jelly Olympic curl bar, punctuated by cotton socks, hangs above—is both a polymorphous pulsating creature and narrative of metabolic process. Like TRANSEXUALIS and the transcendent Jim Otto Suite (both works 1991), is all verb rather than noun. We may speak of them as sculptural works but they express the condition of “-ing.”

Even his drawings are diagrams and embodiments of living systems. Stadium (1991), purposely positioned as the first work of the exhibition, contains a plan of the system you are about to encounter; where football drills on a playing field become the sucrose producing, gonadal, intestinal, rectal, hypertrophic forces of bodies3 cut from organic chemistry, biology, internally lubricated plastics, rock climbing, physiology, and industrial materials such as the iconic petroleum jelly whose entropic tendencies over time (stains, discoloring) are not signs of wear so much as testaments to Barney’s interest in what happens to physical materials as they are subject to pressures and forces over time.

Here is one of the most misunderstood aspects of Barney’s work: he does not work on a human but rather a glacial timescale, unafraid to take eight years to make The Cremaster Cycle (1994–2002) or River of Fundament (2006–2014); the “Drawing Restraint” series began in 1987 and shows no sign of concluding. Each of his works—whether film, sculpture, or video action—should be experienced as an instantiation of an alive system in time, joints and materials that are always striving to become rather than being.

Aligned with this is the necessity of including Barney’s titles and lists of materials with, and as, the work. For instance, the full title: TRANSEXUALIS (decline) —-HYPERTROPHY (pectoralis majora) H.C.G. —-JIM BLIND (m.) —-hypothermal penetrator OTTO: Body Temp. 66 degrees (1991) not only links the creation of aesthetic form with the process of weight training (hypertrophy) where muscles are built by tearing and scarring but introduces, as a detail, H.G.C. H.G.C. is Human Gonadotropin Hormone, which is produced during pregnancy, but “when injected intramuscularly, stimulates testosterone production in the male athlete, which in turn enhances athletic performance.”4

It is therefore unfortunate that the gallery maintains the convention of the checklist, which one must ask for at the desk. CONSTIPATOR BLOCK: shim BOLUS – OTTOshaft – (transverse) TFE squat –HEMORRHOIDAL DISTRACTOR 5 (1991) might read like a visual diagram or science experiment, but that is the point. Barney’s work does not follow the rules of the white cube—it always exceeds and forces us beyond, challenging the very definition of art and objecthood in times deformed by the art market. But none of this lessens its impact, which is more like being injected into the body of a David Cronenberg film than an afternoon visit to a Chelsea gallery show. It is all guffaws, goose bumps, and goo, infused with the groans of the grotesque.

One in a series of exhibitions and bodies of work referred to as the “OTTO Trilogy”: “Facility of Incline” (Stuart Regen Gallery, Los Angeles, May—June, 1992); and “Facility of Decline (Gladstone Gallery, New York, October 1991 in New York); OTTOshaft (at Documenta IX, 1992).

Maggie Nelson, “On Porousness, Perversity, and Pharmacopornographia,” in OTTO Trilogy (New York: Gladstone Gallery, 2016), 19.

Jim Otto, the center for the Oakland Raiders from 1960 to 1974, “was the first player in the NFL to choose the jersey number 00, a reference to his palindromic name. Otto underwent twenty-eight knee operations, nine of which were performed during his playing career. He was fitted with prosthetic knee joints made from Teflon, a self-lubricating plastic whose chemical makeup lends it an intrinsic resistance to friction.” Matthew Barney, “Playbook 91-92,” in OTTO Trilogy, 175.

Matthew Barney, “Playbook 91-92,” in OTTO Trilogy, p. 176.

Maggie Nelson, “On Porousness, Perversity, and Pharmacopornographia,” in OTTO Trilogy (New York: Gladstone Gallery, 2016), 19.