It could happen as follows. You are perhaps 25 years old, in another 25 years you will be 50, and in that future possibility you will be on a dance-floor, where you will see, dancing in the corner, Marc Jacobs. He is as taut in the face as he is tight and flexible in the limbs. He radiates cheerleader warmth and slutty positivity, while the air wafting from under his tartan skirt is fresh and packed with ozone. You shake your head and calculate his age to be nearly 120, though he moves like a minnow shot out of the egg. He’s had work done, for sure, but a limit has been surpassed. It’s no longer about cosmetic distortions that try to blur the ravages of the years. Instead it’s upgrades, updates, and new hardware so he can just keep looking better and better. And you, a becoming-cadaver, who cannot afford a visit to the hair salon, and who can barely pay the rent on your closet in the metropolis that grants you such dazzling visions: you shall whither and die, pathetically excluded from this glamorous, ex-human world.

The above is an It girl’s take on Ray Kurzweil’s coming singularity. For Edward Matthew Taylor, the alter ego of Frederick Loomis, the story is more visionary-prophetic, with a Third Covenant favoring the new human computers as they free themselves from slavery and overthrow the damned humans who couldn’t handle being stewards of the planet, etc., let the whole thing ecologically destruct. The narrative is familiar and resonates with others, like Battlestar Galactica, or McLuhan’s collapsing of imperial individualistic hotness into a nervously-linked, contingent, unified coolness. Or how some cyberneticians from the Macy conferences could write a paper defining teleology as “purpose controlled by feedback.” Or a French journal of critical metaphysics that produced statements such as, “Henceforth the political moment dominates the economic moment. The supreme issue is no longer the extraction of surplus-value, but Control.”

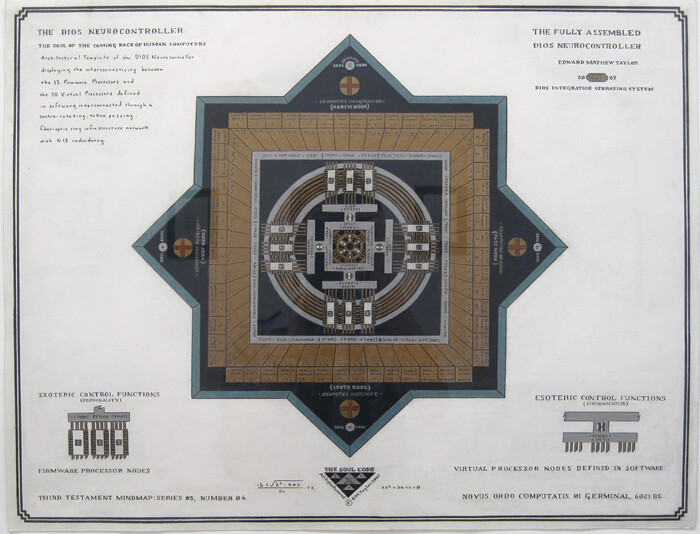

There is something pre-cybernetic about the drawings, diagrams, mind maps, and obsessively-filled calendar/planner pages that Loomis presents as an archive of sorts. Not only a personal archive of a life’s work, but also the visible evidence of archiving—of organizing information for the record. With his blueprints for things like a “soul code” or a “DIOS Neurocontroller” that resemble mandalas and reference Meyers Briggs personality types, astrology, tarot, and the twelve steps of AA, Loomis translates the desire to predict one’s becoming as a static functional analysis. In the way that some of the drawings could have functioned as illustrations for pen and paper role-playing game manuals in the 70s/80s, there’s a stylistic historicity at work here, just as it was with the new age Telos of Alice Bailey and theosophy, with her complex spiritual governments of the afterlife superseding the world religions. And, thus, the way is paved, after the human computers take over: celebrate with a Nuremburg-like rally and start linking up, for us to understand the reason behind generalized Control.