He was considered a lightweight in the early days of post-minimalism but for decades Bruce Nauman has been praised as one of the most wildly influential artists of our time. His video performances with the sounds of their own making hover between tedium and enthrallment, banality and profundity, repetition and distortion. Nauman’s art probes the failure of language and the betrayals of the body and what used to be known as “the eternal verities.” One Hundred Live and Die (1984), his huge flashing neon wall piece at the Benesse House Museum on the Japanese island of Naoshima, proclaims a litany of one hundred oxymoronic alternatives: “LIVE AND DIE, LOVE AND DIE, SHIT AND DIE, PISS AND DIE, EAT AND DIE, SLEEP AND DIE, HATE AND DIE,” and their opposites, “EAT AND LIVE, SLEEP AND LIVE, LOVE AND LIVE, HATE AND LIVE.” His Clown Torture video installation (1987) is as excruciating to listen to as it is to watch. Nauman’s art goes straight to the crux of the human condition.

One of his best-known early video performances is Walk with Contrapposto (1968), in which the young Nauman sashayed back and forth along a narrow corridor, swinging his hips from side to side.(1) His exaggerated sway from one hip to the other—absurd, infuriating, and comically sexy as well as grotesque—embodied a classical Greek pose that implied past and future movement in an attempt to make a statue seem more alive. He made use of his body as a template in videos and sculptures. Installed at the Whitney’s 1969 exhibition “Anti-Illusion: Procedures/Materials,” the narrow corridor he had used as a video prop became a sculptural object (entitled Performance Corridor) that referred to his own absent body. He tested existential limits.

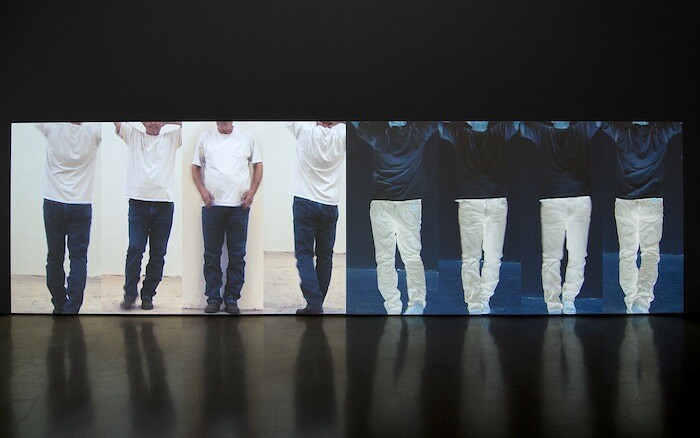

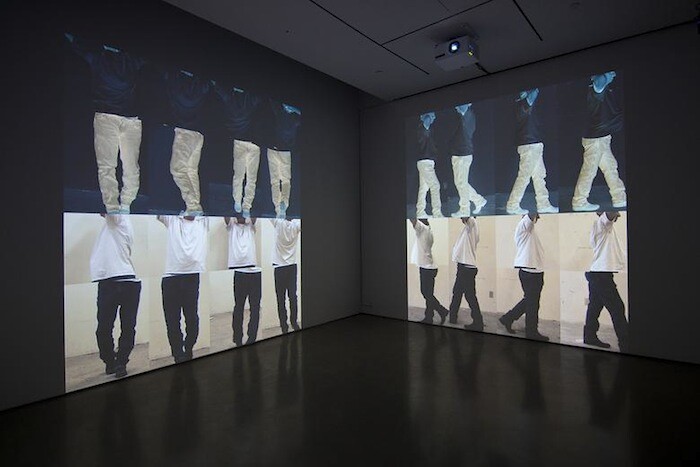

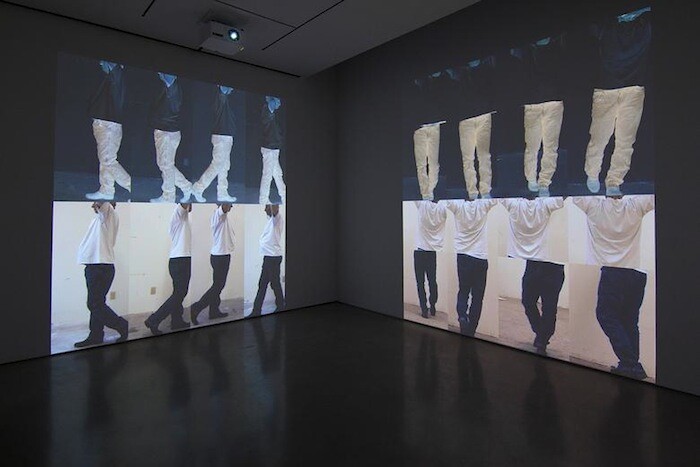

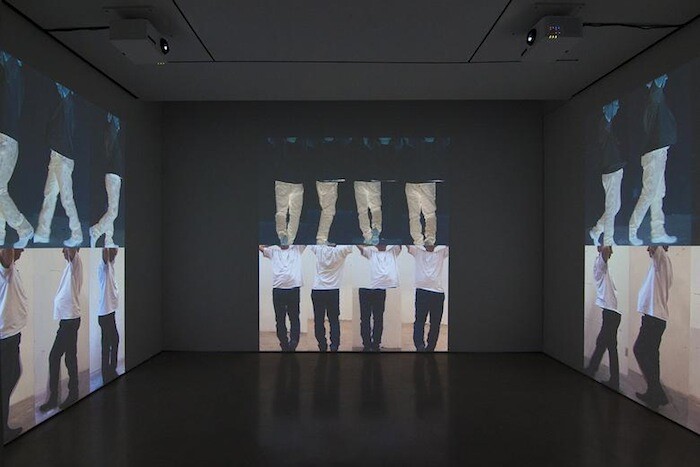

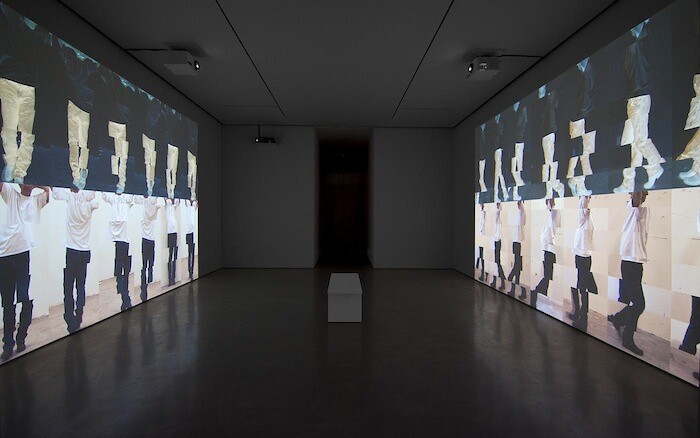

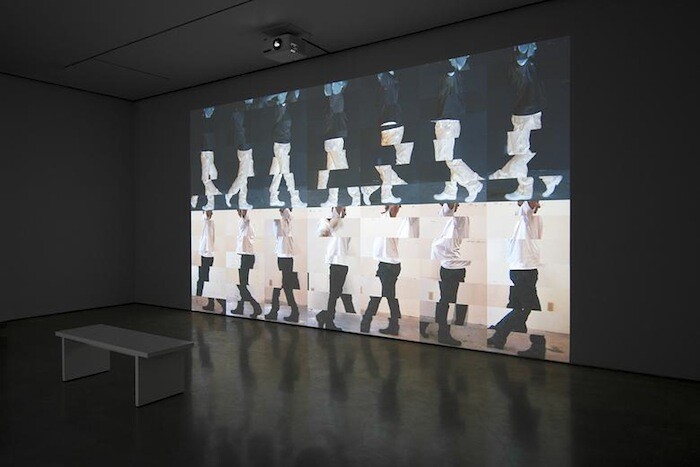

The installation Contrapposto Studies i through vii at New York’s Sperone Westwater (the Philadelphia Museum of Art is showing an alternate version, Contrapposto Studies, I through VII [2]) is an elaborate remake of that early video, and Nauman’s first major work since he represented the US in the 2009 Venice Biennale. The new Contrapposto Studies sum up his lifelong concerns while providing a fuller experience than the original work. In the context of a different century, these seven large-scale, high definition projections with sound revel in the aspect of time as it breaks through the limits of video space. Time disintegrates the moving figure of the aging artist, it wraps around his body, dematerializes its singularity, fragments his figure beyond comprehension. If the principle of Contrapposto added the potential of movement to figural sculpture, it also hinted that a statue need not be an inanimate object: it could contain the germ of motion, could question stasis and time itself. If Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912) raised a similar question at the start of the modernist century, Nauman, using his own body as the moving artwork, raises the dilemma anew in our own increasingly anxious context. He progressively slices and dices his own image by means of the filmmaker’s time-enabled and time-defying craft: the edit, the cut, the juxtaposition, the mismatched image. Nauman moves in these seven studies from a simple dichotomy of positive and negative, forward and backward, to increasingly complex forms of rotation and simultaneity. Progressing through them, you can’t help feeling that time is mocking space.

When we get to the final studies in the gallery’s third-floor “moving gallery” (i.e. the large elevator), we see that Nauman has sliced his own figure not only vertically into seven off-kilter parts: head, shoulders, torso, hips, thighs, legs, and feet, all of which move every which way at once, but also sideways into seven variations. He has created an inexplicably complex choreography that conjures not only Duchamp’s nude but also a dysfunctional chorus line or the Surrealist cadavre exquis. As the parts of the body disintegrate into impure abstraction, it also becomes a formalist dream of random patterning. And let’s not ignore the number seven, an existential digit that implies the days of the week, the genesis of the world, and the epitome of luck itself—a loaded number that has the concept of past and future time written all over it.(3) Moreover, the soundtrack of incidental studio noises in those final two Contrapposto Studies builds in intensity to become an extraordinary post-Cagean symphony. Nauman’s apt remake is a remarkable dance to the music of time.

(1)That early piece was preceded by and may have been provoked by his earlier related video titled Walking Around the Perimeter of a Square in an Exaggerated Manner (1967). (2)The two installations complement each other. Where, at Sperone Westwater, Nauman’s image in the projections is rendered in positive while walking backwards and negative while walking forwards, the opposite applies at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (the exhibition runs September 18, 2016–January 8, 2017). (3)Nauman’s Body Pressure (1974)—a performance in which he pushed his body against a plate of glass, while thinking (as he noted at the time) of “an image of yourself on the opposite side … pressing against the wall very hard”—was the first of Marina Abramović’s “Seven Easy Pieces” (2005) at the Guggenheim, in which she re-enacted seven historically significant early works of performance art. With the Contrapposto studies, Nauman joins a number of twenty-first-century artists who have turned to remakes. As time stopped progressing when the twentieth-century faith in a glorious future ceased to be believable, it skidded to a stop in countless works as video loops replaced linear narrative and “Make it Again” became more relevant than “Make it New.” While Abramovic’s “Seven Easy Pieces” may have seemed self-serving and Barney’s current video replay (“Facility of DECLINE” at Gladstone Gallery, reviewed for art-agenda by Thyrza Nichols Goodeve on October 14, 2016) with props from the 1991 exhibition that launched his career might be disappointing for those who saw the original performance (in which Barney, naked in a harness, navigated the ceiling using ice-clamping screws), Nauman’s elaborately simple and infinitely complex remake carries its original to a satisfying conclusion.