It is now impossible to speak of Ana Mendieta’s pioneering, ritualized, land-body performance art without referring to the still unsettling manner of her untimely death—fallen, pushed, or thrown from a 34th-story window on Mercer Street, New York.

Back in 1988, shortly after her husband Carl Andre was acquitted of Mendieta’s murder, monochrome painter Marcia Hafif invited me to a dinner party in her loft. She neglected to tell me the purpose was to welcome Andre back to the art world. And so I found myself seated opposite him, quite speechless, at a long table of minimalists and monochromists. The conversation started innocuously, with a discussion of front-page items from the day’s New York Times. It was the summer of the circling garbage barge, which was traveling up and down the Eastern Seaboard, unable to dispose of its trash. “In some places,” one person remarked, “they just throw their garbage out the window.” Another guest added that in Rome, throwing something out the window on the New Year was believed to bring good luck, and a third regaled us with how he was narrowly missed by a milk bottle that fell from a fire escape. Each person added another out-the-window anecdote, oblivious to the return of the repressed. Carl Andre’s face went from pale to purple. Later, as we were leaving, I remarked to another guest, “I can’t believe you were all telling those out–the-window stories.” Her puzzled response: “We were all doing what?”

I recount this anecdote not to revive a painful moment in the art community but to note that the repressed inevitably returns. Mendieta’s primary materials were—or so we once thought—mud, sand, leaves, and earth as she merged her body or its outline with the ground. Her performance projects tend to submit to the effect of gravity. So do Andre’s, which might have been a source of their ill-fated attraction.

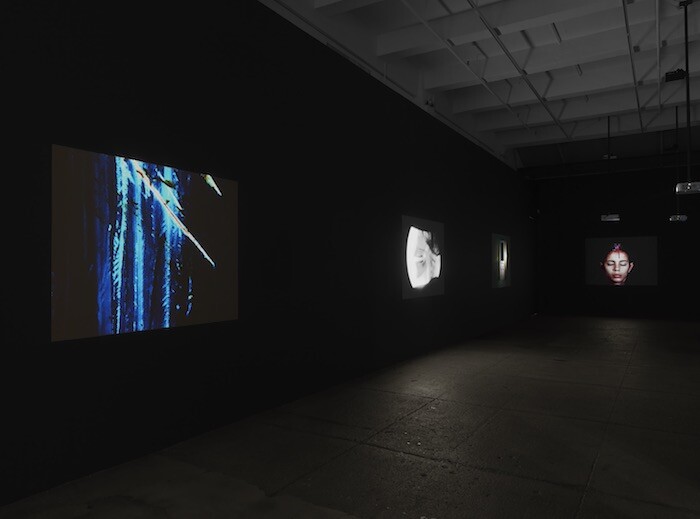

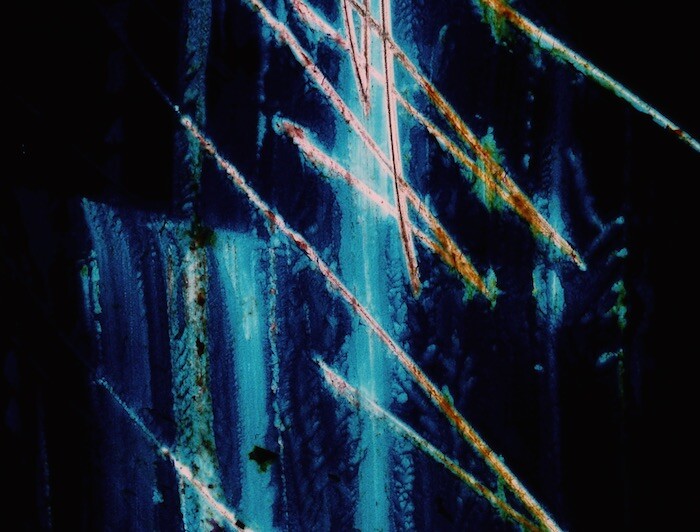

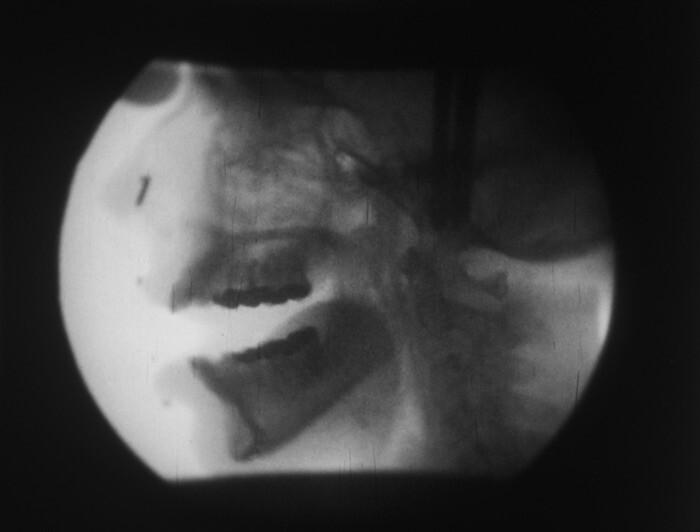

“Ana Mendieta: Experimental and Interactive Films,” an exhibition of her early and recently discovered film works, repositions the Cuban-American artist as a radical film innovator at the very start of her career. Who knew? This show, the first full-scale gallery exhibition devoted to her films, greatly expands the range of her work and places film at its heart, rather than at its periphery. It includes 15 of the 104 films Mendieta made during her short life. Nine of them, recently discovered by her estate and transferred to high-definition digital media, have never previously been shown. Curiously, this show also makes her work even more prophetic—not only in terms of her life but in terms of contemporary art history. Like many other artists of the early 1970s, Mendieta’s filmic works from her days as a student at the University of Iowa explored the basic possibilities intrinsic to the material of film. Untitled (c. 1971), a jumpy, streaked, and speckled blue abstraction, incorporates scratches and flaws in the emulsion. Door Piece (1973) zooms slowly in through a glass door to a spinning fleshy lump that comes into focus as her own mouth and tongue. X-ray (c. 1975) is an unnerving, live X-ray of her skull, its jaws opening and closing while she pronounces vowels and consonants in a speech test. A 1975 work, Butterfly, makes use of polarized graphic effects as her spectral body sprouts iridescent wings. But most surprising to those who know Mendieta’s work through her performance and earth works is the fact that one of her earliest filmic preoccupations was blood.

Moffitt Building Piece (1973)—provoked by the murder of a fellow student—shows a sidewalk stained with blood and viscera. Most passersby pass by. Some glance down and keep walking, some pause briefly, others avert their glance, and one woman stops to poke at the blood with an umbrella. In Sweating Blood (1973), the blood apparently comes from within. A shot of Mendieta’s sweet expressionless head shows her painlessly sweating blood: it drips down her face as if she were some miraculous holy statue come to life. In Dripwall (also 1973), the blood functions as an uncanny art material or holy shroud, inexplicably streaking a white square.

The exhibition at Galerie Lelong coincides with a touring museum exhibition, “Covered in Time and History: The Films of Ana Mendieta.” Containing 21 of her films and videos, the show was organized by the Katherine E. Nash Gallery at the University of Minnesota and is now on view at the NSU Museum Fort Lauderdale (through July 3, 2016). While the focus of that show is on her later performance work and the “Silueta” series, Galerie Lelong addresses Mendieta’s early experimental use of the medium, and includes archival materials such as film reels, announcements, and notebooks.

The late John Perreault, who once taught in the art program at Iowa and knew Mendieta since her days as his student there, sets the record straight in a brilliant catalogue essay, the last piece he wrote. “She was no ordinary artist and her art requires new methodologies,” he pointed out, stressing Mendieta’s “politics of spirituality” and “politics of exile.” Her father participated in the Bay of Pigs and was imprisoned by Castro: at the age of 12 Mendieta was abruptly sent with her sister to a Catholic relocation program in the United States, which remained a lifelong trauma. Perreault also reminds us of some forgotten aspects of early 1970s art, which, along with other post-Minimal attempts to rethink the nature of art-making, saw the birth of feminist art. While Mendieta, who performed in two of Robert Wilson’s early theater pieces (Handbill and Deafman Glance, both from 1970), may have been inspired by the Viennese actionists, Hermann Nitsch’s bloody rituals, Rafael Montañez Ortiz’s fowl decapitations, and Vito Acconci’s Seedbed (1972), Perreault points out that her own art had more in common with older female contemporaries who were exploring the female psyche and body—among them Carolee Schneemann, Hannah Wilke, and Mary Beth Edelson. Have we totally forgotten the almost obligatory worship of The Great Goddess among many first generation feminist artists?

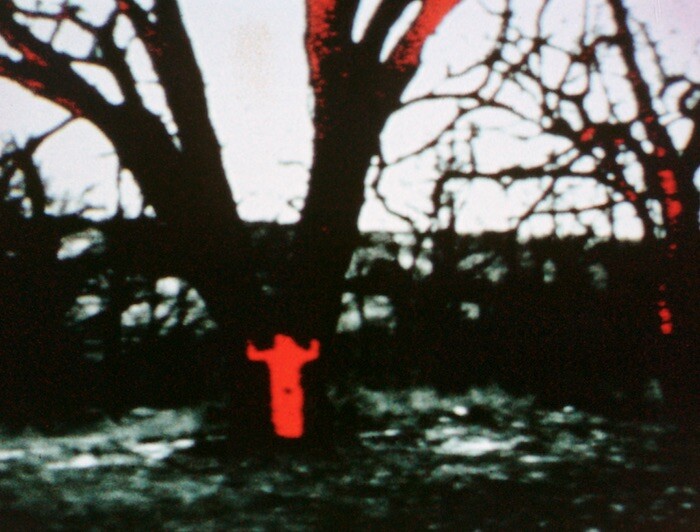

Mendieta went further: Perreault cites her as saying she thought of herself as “a shaman of the Neolithic.”1 She retained innate connections to the Catholic and Santeria rituals of her childhood in Cuba, both of which involved blood and sacrifice. In her early performance piece, Chicken Piece (Chicken Movie) (1972) she held a bleeding headless chicken (as if in answer to Ortiz) until it died; in Bird Transformation (also 1972) she covered a performer with white chicken feathers. Inscribing her shape into the landscape, she made gunpowder and firework silhouettes (which she called “Siluetas”), obliterated herself in mud or sea, blended with the elements and dissolved into nature. She explained: “I have been… exploring the relationship between myself, the earth, and art. I have thrown myself into the very elements that produced me, using the earth as my canvas and my soul as my tools.”2

In the catalogue accompanying the museum exhibition, Rachael Weiss notes that Mendieta, who made several trips back to Cuba in 1980 and ’81, made works there (including one in a sacred cave) and was an influence on Tania Bruguera.3 In fact, Mendieta mentored and influenced an entire generation of Cuban artists, including José Bedia, as well as Americans such as Janine Antoni. After Mendieta’s death, Carolee Schneemann made a tribute to her with blood and ash in the snow (Hand/Heart for Ana Mendieta, 1985); Nancy Spero paid homage with bloody handprints on a wall. Since then, feminist artists have staged demonstrations in Mendieta’s memory at shows of Carl Andre’s work. Last year, at Andre’s retrospective at Dia:Beacon, they staged a moving “cry-in.” Ana Mendieta, who thought of herself as a Neolithic shaman, could be approaching iconic status.

Lynn Lukkas, “Forever Young: Five Lessons from the Creative Life of Ana Mendieta” in ibid.

Lynn Lukkas, “Forever Young: Five Lessons from the Creative Life of Ana Mendieta” in ibid.

Rachel Weiss, “Difficult Times: Watching Mendieta’s Films,” in ibid.