May 28–June 27, 2015

In the “Dada Manifesto on Feeble Love and Brittle Love” from 1920, Tristan Tzara famously provided instructions on how to write a Dada poem: get a newspaper and some scissors, snip out individual words and put them in a bag, shake it and then withdraw slivers of text, write down the words in the exact order in which they appear, and—voilà!—poem. Yet even more provocative than the method is Tzara’s claim that, “The poem will resemble you.” Similarly, although William Burroughs utilized the cut-up technique to undermine authorial intention and the way in which information serves as a means of control, the writings he produced in this manner continued to bear the impression of his obsessions: the police, queer sex, death.

Over the course of 26 Sundays in 1977, Lorraine O’Grady took scissors to the New York Times to create a series of text-based works recently on display at Alexander Gray Associates. If Tzara was convinced that his aleatory approach to writing a poem would nevertheless reflect the author, what does this involve for O’Grady, a crucial yet still somewhat overlooked artist of Caribbean descent who produced an important body of work in the late 1970s and early 1980s, including “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire” (1980–83), a set of performances/activist interventions for which she donned a dress made of white gloves and, most famously, crashed the opening of a New Museum show (“Persona,” 1981) in order to draw attention to the absence of nonwhite artists?

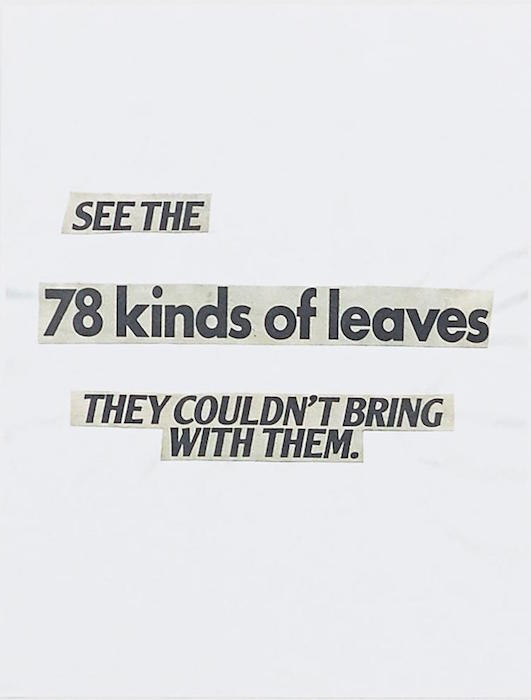

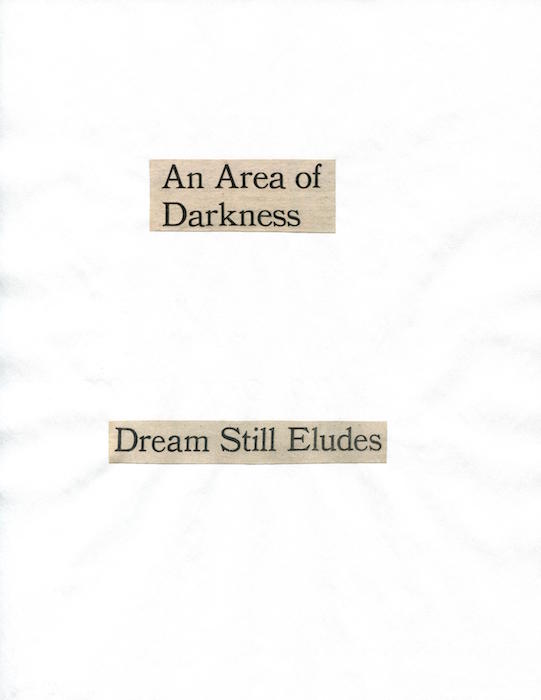

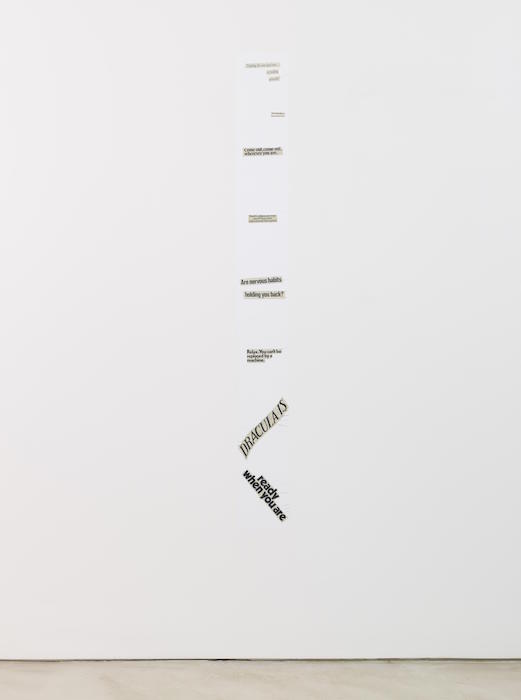

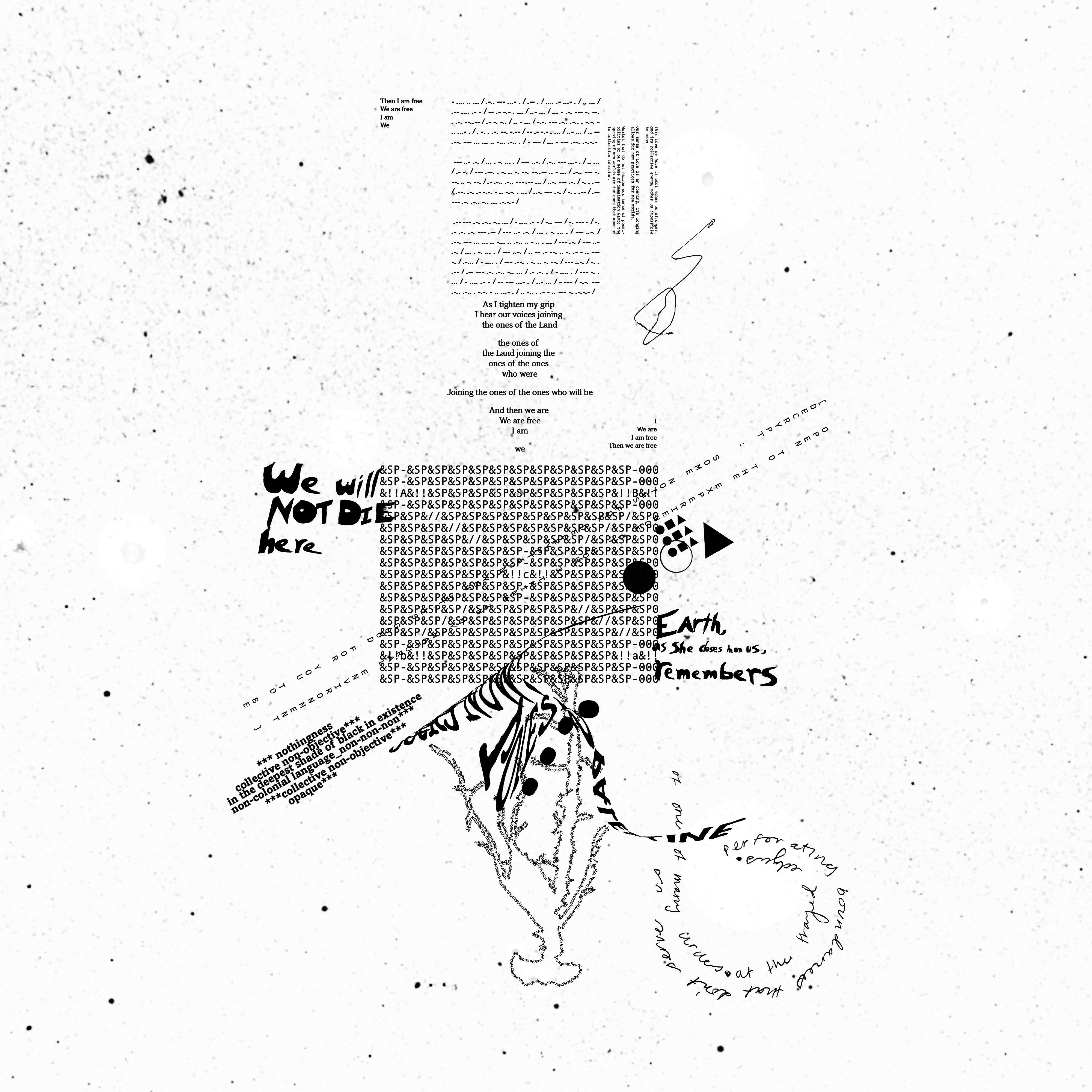

O’Grady’s exhibition at Alexander Gray was another iteration of the archival presentations of her work that have occurred at a number of different venues over the past decade or so. Cutting Out The New York Times (1977/2015) consists of 5—out of the original 26—series of newsprint-on-paper works that have been scanned, output on roughly letter-size adhesive paper, and affixed directly to the gallery’s walls with anywhere between 6 and 13 sheets per work, with 4 oriented horizontally and one installed vertically. O’Grady clipped phrases from the New York Times and scattered them on the floor, combining randomness with agency to produce her texts. Each series starts with words and a date that almost function as a title page. Made with phrases from the Sunday, September 25, 1977 edition, “the renaissance man / is back in business” alludes to race relations, contemporary art, female artists, and film as spectacle with phrases that are direct yet made elliptical when combined on each sheet and across adjacent pages.

O’Grady keeps the collage aesthetic fairly basic—words are tilted, staggered, and generally centered, but not layered or foregrounding of their materiality—in order to demonstrate clearly both a method and a message. From “M∙ss∙ng / Persons” (10/23/77): “Marathon Mother / Is Considering a Change”; and “‘Oh, God!’ / Why Has Estrogen Fallen On Such Difficult Times?”; and “or / young, black and / With A Greenhouse Dream.” Like the best experimental poetry, Cutting Out The New York Times both mocks and mines the more conventionally poetic. Upstairs at Alexander Gray, Rivers, First Draft (1982/2015) expands this approach into a personal-social narrative documenting a public art performance O’Grady orchestrated in Central Park in 1982. Mirroring the installation downstairs, Rivers, First Draft is installed in six mostly horizontal rows of photographs ranging from five to thirteen per cluster.

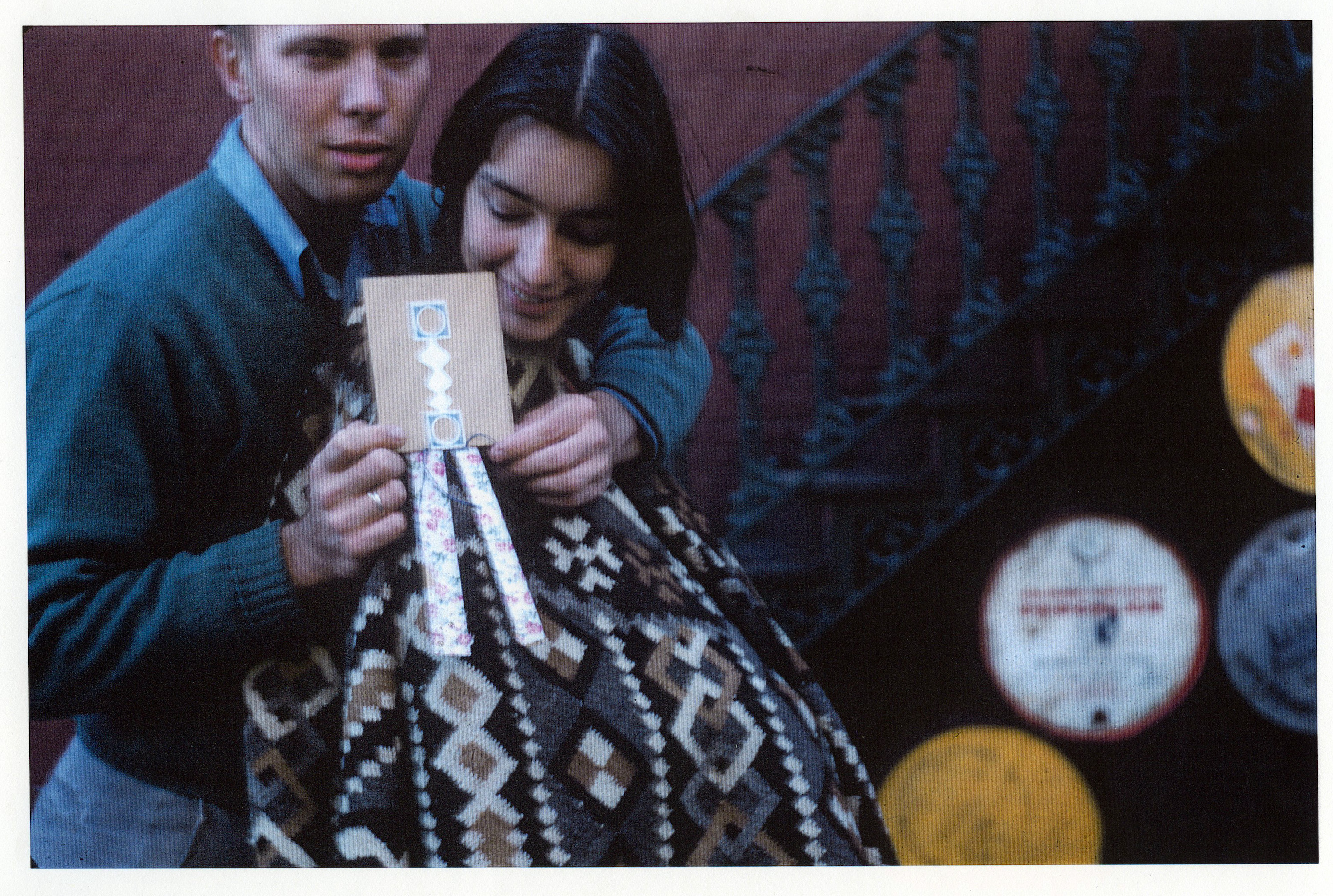

Utilizing a variety of performers in bright monochromatic clothing, each series illustrates distinct periods from O’Grady’s life: girlhood and young love, social and cultural pressures, encountering thresholds and becoming an artist (O’Grady in red spray-painting a stove the same color), and the final crossing of a stream guided by a man in a gray raincoat and hat wearing a costume of a small boat called The Nantucket. (O’Grady grew up in New England.) Precisely choreographed, with characters representing various symbolic figures, Rivers, First Draft tilts between the deeply personal and the universal as it evocatively charts a process of individuation. Its specific reference is the experience of a black female artist, and yet the documentation and its presentation at Alexander Gray remains open-ended enough—perhaps even, again, poetical—that the associative logic necessary for making sense of it all invites the viewer to become a retroactive participant in the work.