In the context of the current Turkish political climate, there is a tongue-in-cheek criticality to the work of Vahap Avşar. Just across the street from the New Museum, in the swanky Charles Bank Gallery, the multifaceted work of this Turkish artist troubles the viewer—just enough for a double take. His work is charged with politics, in particular the local politics of New York. But expression is not easy. The mixture of aesthetics—found imagery, painting, installation, and video—exposes the artist’s struggle with different media to represent Avşar’s immediate concerns ranging from the militarization of Turkey to delineations of public space.

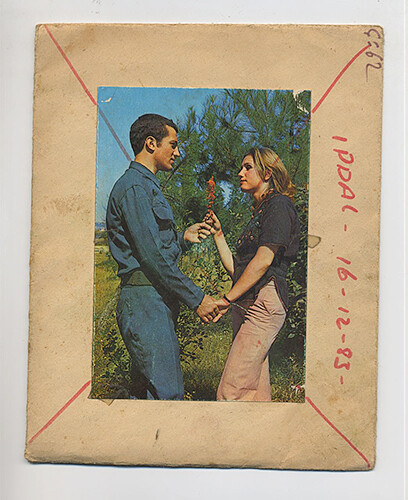

The first striking note of the show is the abundance of red X’s crossing out seemingly innocuous images, be it censorship or the artist’s personal ire. As it turns out, Ipdal (2010) is a series in which Avşar employs these odd postcards rescued from a printer’s collection found in Istanbul. From over 20,000 postcards produced between the late 1960s and 1990s, Avşar chose to enlarge and exhibit those that were marked by the word ipdal, Turkish for “cancelled.” On his website, the artist explains that this particular form of censorship was executed by the military government in the 1980s in an effort to eradicate anything that did not fit into its vision of Turkey. Included in these “cancelled” images are soldiers in overtly staged romantic poses with women. The dates on the images indicate that they were all “cancelled” on the same day in 1983, highlighting the swift character of the censorship. The artist’s decision to enlarge these postcards reads as both a formal and political gesture, and the street-level gallery space becomes a public shaming of the Turkish government—both now and then.

Ipdal is juxtaposed with two abstract canvases titled I.E.D. and W.T.C. (both 2010). They depict a man falling through a landscape of light orange clouds and a vaguely discernible crumbling tower, seemingly crushed by a dense cloud of smoke. As if he were seeking a moment of solace or contemplation in the middle of the disaster, the artist has used subdued colors, yet the tone remains ominous.

There’s nothing subdued however about the police car in the middle of the gallery. It is shocking in a momentary, amusement park-like way, the result of an encounter with the Terminator. But then again, it seems to cry of civil disobedience (and, it must be said, it’s not unlike Gustav Metzger’s destroyed car across the street in the New Museum). But Avşar’s police car was smashed inside the gallery, leaving shards of glass everywhere: it’s a decision that puts out the fire in the kindling sense of danger invoked by the over-the-top Hollywood nature of the work.

The best work of the exhibition by far is the video Tekmil (2010) in the downstairs screening room. The close-ups of a soldier’s face reveal beads of sweat, humanizing the military. It’s an image rarely seen in the context of a developing country with a strong military culture like Turkey. But even for a native-Turkish speaker like myself, the soldier’s words are extremely hard to follow. His off-screen interrogator asks a series of questions, which in the end become so much background noise, exponentially expanding on the tension created upstairs.

Exhibited shortly before national elections in Turkey, Avşar’s work has the potential to be read unilaterally. But it is the shifting idiosyncrasies that mark his work and the precise imprecision of the exhibition that make it all the more obvious that the artist is moved by personal reasons beyond the outcries of a larger political agenda.