Several installations from P.S.1’s inaugural exhibition “Rooms” (1976) have left a lasting mark on the institution—literally so, as they’re embedded into the building. In the attic, Richard Serra’s steel-beam Untitled is sunk into the concrete; Alan Saret’s The Hole at P.S.1, Fifth Solar Chthonic Wall Temple pierces through a wall. These enduring physical remainders make the history of P.S.1 inseparable from that of site-specificity. Through considerable renovation, the building has retained the character of its Romanesque Revival architecture and traces of its original use as a school. Its spaces are so emphatically idiosyncratic that, even in the case of artworks long absent, it’s difficult to view a new installation without also perceiving the after-image of what stood there previously.* Though it’s been covered over for years, you can still see the cut marks from Gordon Matta-Clark’s Doors, Floors, Doors in the floorboards.

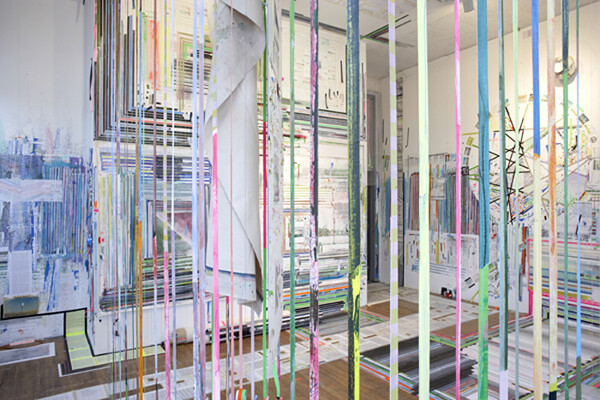

At “Greater New York 2010,” the museum’s first major exhibition since the departure of its founding director Alanna Heiss and its re-christening as MoMA P.S.1, the emblematic piece might be Franklin Evans’s timecompressionmachine, (2010) which occupies the same first-floor corner gallery where Matta-Clark once sawed through the ceiling and floorboards. Evans has smothered the space with colored tape, mylar, canvas, and, most curiously, numerous press releases from recent gallery exhibitions. It’s the latter element that reverberates with GNY10 overall, since a substantial swath of the same or nearly identical work has appeared elsewhere in New York within the past nine months: by Tauba Auerbach (at Deitch Projects in September), Zipora Fried (On Stellar Rays, September), Tommy Hartung (On Stellar Rays, November), David Benjamin Sherry (Sikkema Jenkins & Co., March), and Amy Yao (Jack Hanley Gallery, May—that is, concurrently), to name just a few. If Evans’s installation “compresses time” by incorporating past exhibition press releases into a spatial collage, GNY10 accomplishes a similar effect by including so much recently exhibited artwork.

The resulting moments of déjà vu are experiences markedly distinct from the chance discoveries of half-hidden artworks that traditionally typified a visit to P.S.1. Those sorts of surprise encounters were certainly plentiful during GNY’s previous iteration in 2005—an exhibition of such density that artworks were stuffed into every available crevice—but are largely absent this go-round. It’s difficult to state forthrightly whether this should be attributed to the shared vision of its three curators, Klaus Biesenbach, Connie Butler, and Neville Wakefield, or to the discreetly shifting sensibilities of the city’s artists, but this much is clear: big gestures and eccentric interventions have lost out to works of modest ambition and diminutive materials. The exhibition’s profusion of photography comes primly framed, mixed-media pieces are tidily arranged, and signs of mess remain sealed within video documentation (as in the case of deliriously gooey investigations by Alex Hubbard, Gilad Ratman, and Leidy Churchman). In deference to two years’ backlash against Wall Street, material excess of any kind seems frowned upon.

This pared-down approach has the advantage of giving artists ample maneuvering space to showcase their full repertoire. For instance, Leigh Ledare has assembled a suite of photographs exploring his unsettlingly explicit yet tender relationship with his troubled mother that spans eight years. There is ample evidence that GNY10 aspires to the condition of multiple solo shows, or, in Ledare’s case, even retrospectives-in-miniature. Of course P.S.1 has an extensive record of solo and retrospective exhibitions—perhaps most notably of influential-yet-overlooked figures like Jack Smith or Manny Farber. It’s a new development to apply that same treatment to younger artists, who often debut at P.S.1 with a single original piece specific to the building. Of these, there are comparatively few: in the boiler room, Aki Sasamoto has annexed a lair-like alcove, and Saul Melman has taken to periodically gold-leafing its arcane plumbing fixtures; Evans and Dominic Nurre make room-sized rubrics out of their respective corner galleries; and David Brooks has turned the duplex space into a rainforest environment devastated by concrete. In general, however, most work feels shipped in from elsewhere.

Rather than conjuring the image of a building overrun by artists busily installing up until the press preview, GNY10 suggests an alternate scenario: artists present through the duration of the exhibition as contributors to an extensive schedule of live programming. Every weekend, P.S.1 will host performances, lectures, and artist “office hours,” thus framing the works on view as the backdrop for on-site activity. This implies that private studio practice now needs to be supplemented by a live public component. In this respect, Naama Tsabar’s sound-sculpture Untitled (Speaker Wall) (2010)—which appears to be a black 2001-type monolith from one side, and as a blocky, oversized guitar body from the other—may be the new exemplary model; the piece exists autonomously yet doubles as a musical instrument for performance.

If GNY10 is an indicator of anything, then, it’s a shift in emphasis from site specificity to live programming. Instead of discovering a covert artwork in a stairwell, visitors are now likely to stumble across Ryan McNamara temporarily inhabiting a corridor for his daily performance-cum-dance-class Make Ryan a Dancer (2010). The question is whether this shift is anything more than a consequence of financial straits. After all, P.S.1 pulled the show together with an avowedly tight budget, and the time an artist devotes to a performance is less dear in an accountant’s ledger than the by-the-hour expenses of installation crews. Or does GNY10’s cocktail of studio-based practice and performance announce a definitive change in ethos, for P.S.1, other institutions, and artists more broadly? That is, will it leave a lasting impression?

* Full disclosure: I probably experience this after-image effect at P.S.1 more acutely than most, since I was employed there in 2006.