Respected artists in their own right, Rosalind Nashashibi and Lucy Skaer have also led a fruitful collaboration since 2005, pairing their unique temperaments in taut, reflexive films and installations. Theirs is a method that emphasizes the transformations, shifts, and slippages that images and ideas can undergo: through the entropic sedimentation of time, for example, or an act of misrecognition (willed or otherwise) with which an artist can build a new language from extant matter.

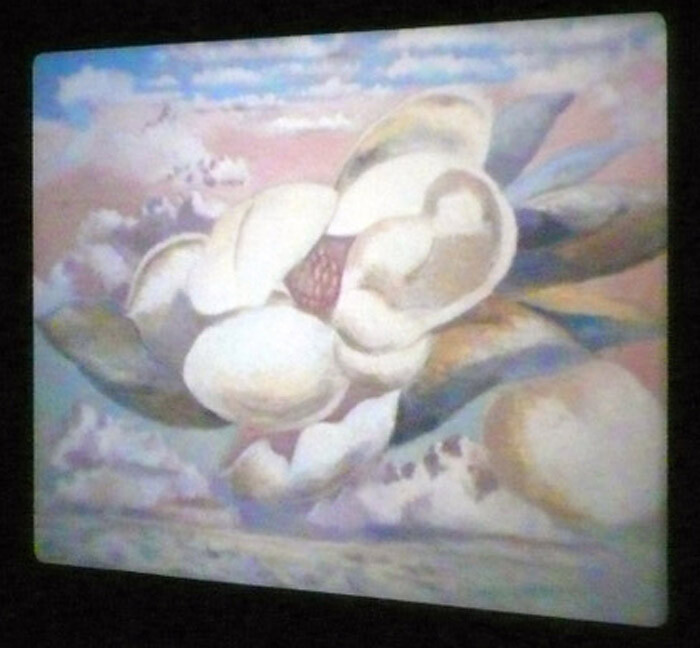

For their first collaborative solo exhibition in the US, the British duo tell two mythic stories with both structuralist and iconographic syntaxes. The single-channel film Our Magnolia (2009) expands outwards, in portentous swoops, from British painter Paul Nash’s Flight of the Magnolia (1944). An official artist for both World Wars, Nash ended his career with an essay and series of paintings, entitled “Aerial Flowers,” that channel wartime paranoia into depictions of flowers hovering like enemy parachutes across the English sky. Nashashibi and Skaer’s associative montage shakily traces a path through figures of mortality and militarism into the neoconservatist age, moving from alternating close-ups of the painting and aristocratic flowers to sequential reframings of the hollowed eye socket of a decomposing whale carcass; two photographs of Margaret Thatcher, shown first on an office desk and again in unflattering close-up; airport security documentation of passenger aircraft; and a heart-rending scene of a female griever in the looted National Museum of Iraq. Her cry punctures the previously mute soundtrack and resounds until the last shot of the film, when Nashashibi and Skaer cover the actual 16mm filmstrip (of footage of Nash’s painting) with a flurry of scratches. These moments have an expressive force unmatched by the rest of Our Magnolia, which approaches but ultimately falters at the threshold of the political.

In Pygmalion Event (2008), Nashashibi and Skaer explore the well-worn Greek myth through footage shot at the Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence, a French chapel Henri Matisse conceived towards the end of his life—right down to the décor and vestments. Matisse’s designs play the role of the statue-made-flesh, given life in scenes of a priest trying on the colored chasubles of the different seasons of the Dominican calendar. The pastel purples, yellows, and reds of the garments, woven with cutouts of clovers, flowers, and crosses, prove jarringly radiant against the priest’s spare, personal quarters. Sacral work here takes form as an everyday ritual carried out before the rhetoric and pageantry of the service beyond the chapel halls, in a setting where transcendental drives assume softer, permeable contours. Responding in kind, the artists film the priest so as to show the in-between moments when he enters a period of prayer and exchanges words with a person off-camera.

These small asides, which occupy many of Nashashibi’s own films, carry across a second, synchronized projection of monochromatic fields, still lifes, and other shots that offer visual and gestural echoes too piecemeal and varied to be merely analogous to the footage of the first. A shot of a rocky hill accompanies a close-up of the yellow palm leaves and black Xs of the red chasuble; and at another moment, a shirtless man mimics the twirl of the priest in a coincidental pas de deux. Desire provides a motivating drive for a film that yields no conclusive shape—only voices to add to the many. Contesting the reductive teleologies that structure many collective beliefs, Nashashibi and Skaer have reread the Pygmalion myth as a narrative of artistic method and creative potentiation.