Muhammed Ahmed Faris is the only Syrian who has traveled to outer space. A colonel in the Syrian Air Force, Faris—the subject of Turkish artist Halil Altindere’s video Space Refugee (2016)—joined the Soviet cosmonaut program in 1985 and was part of a mission to the Mir Space Station in 1987. “Those seven days 23 hours and five minutes changed my life,” Faris told The Guardian.1 He saw this experience as a privilege that he could share with other Syrians through education in science and astronomy, but that was not on the agenda of President Hafez al-Assad, who controlled Syria following a coup in 1970.

When in 2000 al-Assad died and his son Bashar succeeded him, Faris was the head of the Syrian Air Force Academy and a military advisor. To The Guardian, Faris describes both father and son as enemies of the people, who ruled by maintaining their population as uneducated and divided as possible. In 2011, when the revolution in Syria broke out, he marched in Damascus, calling for reform; the next year he defected to Turkey, becoming one of the five million Syrian refugees to leave the country.2

Faris and Altindere met in Istanbul, and the cosmonaut became the subject of a 20-minute video conflating his life story with a crazy, cynical, optimistic idea—if no country wants them, let’s send the world’s refugees to Mars. In the video, Faris describes the difficulties of the journey out of Syria, then talks to fellow refugees, telling them to be patient, to raise their children in the values and traditions of their homeland because they will return. And if not—“I hope we can rebuild cities for them in space, where there is freedom and dignity and where there is no tyranny, no injustice.”

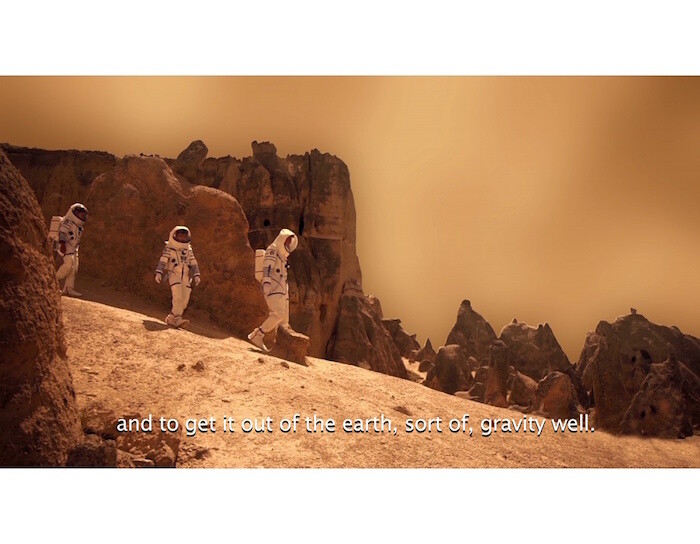

The video then moves on to explore the practicalities of this desperate proposal. It portrays three astronauts as they explore the reddish deserts of Mars and interposes these scenes with interviews with scientists about settling the planet. The Martians, one scientist explains, will have to find ways to grow food and sustain themselves. They will have to bring 3D printers with them, in order to make whatever objects they require. They will need to send thousands of rockets over with supplies. Water is a concern. An architect states that due to the levels of radiation, homes built on Mars will have to be underground. Some of the footage of the astronauts, shot in the volcanic region of Cappadocia in Turkey, is also presented as a virtual reality video titled Journey to Mars (2016). Putting on the headset, the viewer follows the three as they explore the landscape. The immersive technology creates an environment so real that the experience of wandering through the desert feels isolating.

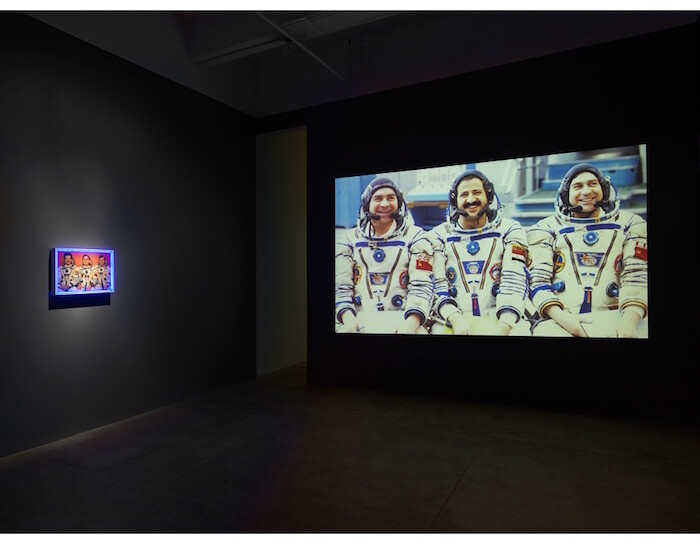

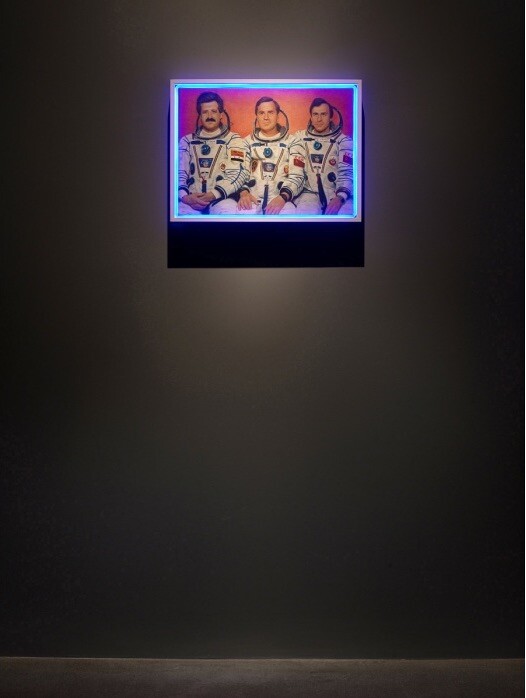

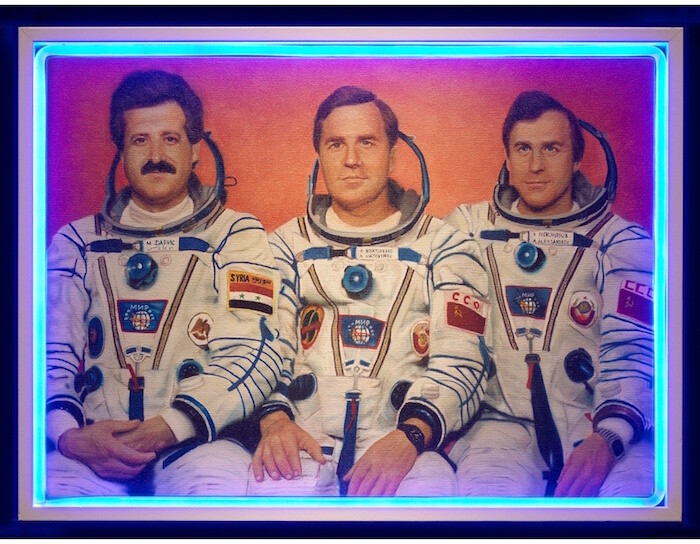

The exhibition design is reminiscent of an old-fashioned space museum, with wallpaper of a galaxy superimposed with an image of Faris in a spacesuit holding onto a shuttle. A Soviet Realism-style oil-on-canvas, encased in an LED frame and titled Muhammed Ahmed Faris with Friends #1 (2016), looks like an official portrait of the cosmonaut and his crew. Altindere’s work relies on the romantic imaginary of space exploration, but the viewer remains aware that its heyday was during the Cold War.

These polarities—the romance of seeing earth from space and the Cold War reality of space exploration, the astronaut-hero and the refugee—are the reason Space Refugee is so evocative and resonant. Though one of the talking heads in the film says we will send humans to Mars in his lifetime, it’s too late for the millions of refugees looking for asylum. The ironic suggestion could be read as cynical, but in Altindere’s work it’s a proposal that hones in on the popular imagination and uses it to draw attention to something else. It’s a strategy he’s employed before: in Wonderland (2013) he created a hip hop video with Roma kids whose Istanbul neighborhood was razed by the Turkish government as part of an urban renewal program. The imaginary of hip hop as an urban, Straight Outta Compton–style phenomenon draws attention to this marginalized urban community’s fate.

Space Refugee was shown at the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein last year, and in a country that has taken in about a third of the current wave of refugees into Europe, it may be the intimacy and warmth of the work—the meeting between Altindere and Farsi which sparked the artist’s imagination—that resonates. In the United States, it is the distance. The exhibition was on view when Donald Trump issued an immigration ban excluding the citizens of seven majority Muslim countries from entering the United States, closing the country’s borders to refugees as well as many legal residents. In these trying times, the humor and humanism of Altindere’s project is effective, but its loneliness and uncertainty are much more poignant. The sentiment in the VR film of walking in uncharted land, in unsteady places, is most descriptive of our lives today.

Rosie Garthwaite, “From astronaut to refugee: how the Syrian spaceman fell to Earth,” The Guardian (March 2016), https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/mar/01/from-astronaut-to-refugee-how-the-syrian-spaceman-fell-to-earth.

As documented by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. See Ariane Rummery, “Syria conflict at five years,” UNHCR (March 2016), http://www.unhcr.org/uk/news/latest/2016/3/56e6e1b991/syria-conflict-at-five-years.html.