For a few years in the mid-2000s, writing made a notable dent in contemporary image-saturated culture—what’s ever more loosely called the society of the spectacle. With the explosion of texting and blogs, written language almost seemed to rival visual culture for the attention of citizens, consumers, and everyone in between. The gatekeepers of all things well-behaved bemoaned the linguistic crudities of texting (lol) and the way in which blogs gave more people an opportunity to express their (sometimes misinformed) opinions (a still prevalent complaint in the art- and music-writing worlds). But this brief efflorescence of the written word didn’t last long, as the clean graphic interface of the iPhone (etc.) reemphasized the visual experience over the linguistic one. Of course, many other factors played a role in this as well, such as the unsustainability of regular blogging without financial recompense. The utopic democracy promised by the Internet since its more widespread inception in the early to mid-1990s (everyone will have a website! omg) only first pushed toward this potential—in my mind, anyway—with the blogspot.com suffix. These days Tumblr pages—granted, a blog, but a predominantly visual one—outnumber those using the more linguistically oriented WordPress, and Facebook is losing its younger audience to Instagram (in the West, at least).

There are two iPads as part of the artworks gathered in the International Center of Photography (ICP)’s third photography triennial, entitled “A Different Kind of Order.” Thomas Hirschhorn’s Touching Reality (2012) is a video that gives a frame to a hand scrolling through images of dead, severely injured, and mutilated victims of war in the Middle East. Images include splattered brains, body parts, and internal organs no longer internal. As the hand pauses over them, it pinches and expands certain images or scrolls back to previous ones. It’s a seeing hand of sorts. Though horrifying, the three-plus levels of mediation—initial image, image downloaded to an iPad and manipulated, image and iPad recorded—mute the images slightly, which would seem to be part of the point. What makes Hirschhorn’s work in general so curious is that unlike most other socially engaged artists, who either create propaganda or seek to counter it, he designs the space around it, but does very little to the propaganda itself (the artist’s background in advertising, in which the object isn’t altered, only the environment for it, probably contributes to this). By putting the resources for propaganda into play—whether war atrocities or the writings of Antonio Gramsci—Hirschhorn short-circuits the relationship between ideology and the gaze.

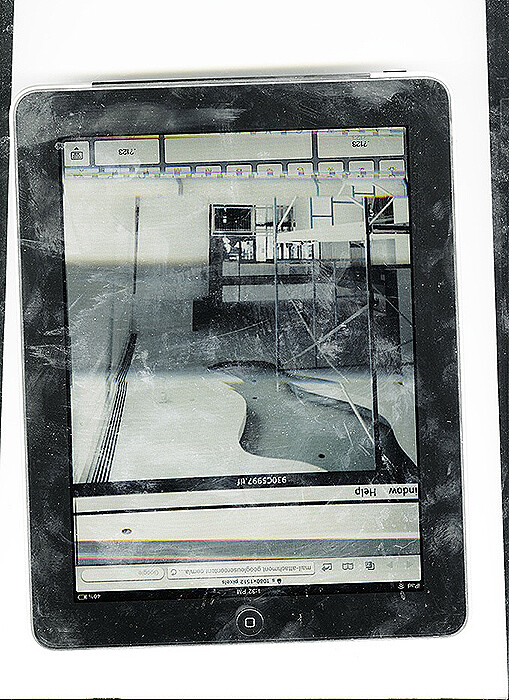

The other iPad appears in work by Andrea Longacre-White that seeks to respond to the institutional context. She took digital photographs of ICP’s interior and transferred them to an iPad, which was then scanned face down. The resulting three large photos on display (all 2013) contain distorted reproductions of the architectural interior, the immediately recognizable tablet screen (complete with fingerprints), and the scan’s stark white background. The look feels a bit messy and collage-like, even if, as with Hirschhorn’s contribution, this is (again) the result of degrees of mediation—image, its scan, then enlarged print. But, in fact, the hand-produced (and hand-produced looking) is one of the main themes running through “A Different Kind of Order,” and the exhibition opens with a few of these: Mishka Henner’s Dutch Landscapes (2011), which substitute colorful geometric abstractions over sensitive areas the Dutch government ordered blurred when photographed by Google Earth; Huma Bhabha’s drawings on photographs she’s taken of ruins around Karachi; and Elliott Hundley’s Pentheus (2010), a large-scale collage of images and texts, with scattered cutout figures protruding from the surface of the work with pins. In retelling—and dismembering—Euripides’s presentation of the Dionysus myth, Hundley introduces another important theme of the exhibition: the body, both under threat and yet like a return of the repressed, asserting its fleshy, messy self into technology’s increasingly shiny sheen.

Albeit much less extreme than in Hirschhorn’s images, this body nevertheless mostly exists in fragments throughout the work on display. Even the fairly conventional portraits in Gideon Mendel’s video and photographs (some of which are installed around ICP’s exterior) show people from different parts of the world standing waist-deep in floodwaters, their legs eclipsed by the surface. Legs and feet feature prominently in A. K. Burns’s video installation, Touch Parade (2011). On five monitors, each presents a different reenactment of fetish videos found on YouTube: in one, the artist’s bare feet work a car’s clutch, brake, and accelerator pedals; in another, she slogs around in muddy water while wearing thigh-high galoshes; in a third, new white sneakers squish vegetables and eggs. While very different from Hirschhorn’s clumps of intestines and brain matter, Touch Parade similarly aims for a queasy viscerality that tears through the veil of a hypermediated society of images. Here, the image is mediated less by technology than by the viewer’s response to it.

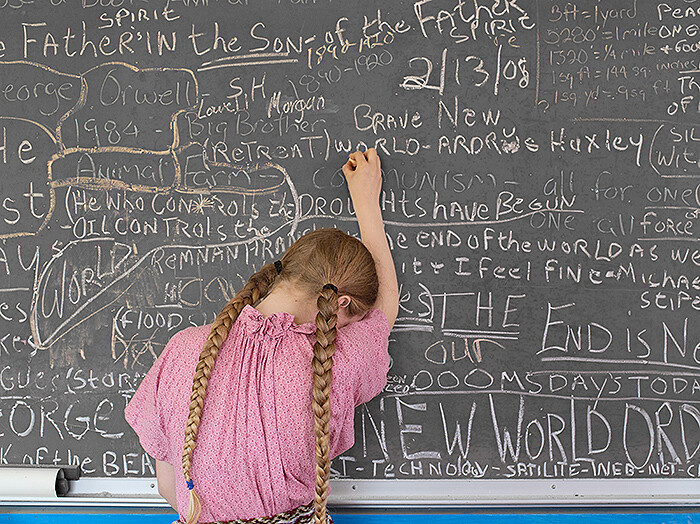

Lucas Foglia’s A Natural Order collects photographs he took of individuals and groups creating alternative economies, communities, and cultures outside of mainstream U.S. society. A couple generations ago, these might have been hippies living on communes, but one of the striking aspects of these works is how they isolate the individual—a bare-chested man in the woods with his possum stew (2006), an exhausted girl standing at a homeschool chalkboard (2008). There’s a rugged individualism (even in the group portraits), and not much sense of infrastructure. One wonders how long these survivalists will actually survive. A very different sense of individualism appears in Nayland Blake’s extensive installation, Knee Deep in the Flooded Victory (2013), combining photographs, publications, and small objects from his personal collection and the ICP archives celebrating gay liberation. As the only artwork in “A Different Kind of Order” that viewers are forced to physically negotiate, Blake’s contribution breaks with what throughout the exhibition feels like last century’s—i.e., static—mode of viewing. The World as Will and Representation (2007), Roy Arden’s hour-and-a-half-long video of circa 28,000 digital images organized by subject—while obviously impressive—is only the most extreme example of this relatively passive spectatorship.

There are exceptions. The most pleasant surprise for me was Oliver Laric’s instigation of a different kind of engagement. His Versions (2010, 2012) are six-to-ten-minute digital videos that fantastically recombine images, and in this sense not unlike two other strong contributions: Wangechi Mutu’s animal, human, vegetable hybrids (pieces that feel less fashiony than some of her other collage-based work) and Walid Raad’s reimagining of the material, psychic, and aesthetic distortions of art and cultural objects from the Arab world. Laric’s Versions brush image and language against each other with a voiceover delivering a simultaneously real and fictional assemblage of theoretical discourse. Both image and text flow according to associative logic and imaginary taxonomies—religious icons, Disney movie characters, sports photos, Iranian military propaganda, etc. At one point, the stilted, official-sounding female voice proclaims, “The set of possible books outnumbers the set of actual books.” It’s an idea represented in a variety of approaches, and with varying degrees of success, in “A Different Kind of Order.”