While driving through the Mojave Desert two hours east of Los Angeles in the area surrounding Joshua Tree National Monument, among the most striking aspects of the scrub-and-bleached landscape are abandoned wooden shacks that regularly punctuate the view. The majority are nothing more than weather-blasted frames with doors and windows gone. Most are the products of a Small Tract Act that lasted from 1938–1976, whereby the federal government sold small parcels of land for cheap to those who built structures on the property and made an effort to inhabit it. As the current vacancy rate shows, most denizens couldn’t maintain a viable existence in the unforgiving desert environs.

It’s to this area that Andrea Zittel moved from Brooklyn in 2000 to make an attempt at total living, which involves designing and building domestic and work spaces, producing clothes, growing food, and having greater agency over one’s social and cultural experiences—all of it done on a relatively small and sustainable level. Although since expanded to 50 acres, Zittel’s experiment is still dwarfed in comparison with, for instance, Donald Judd’s related project for the art of living in Marfa, Texas. (Of course, he initially had many more resources at his disposal.) A one-person Bauhaus, Zittel aims for a milieu of complete design incorporating architecture, furniture, textiles, and housewares as part of an educational process (for her) that serves as a pedagogical project for its recipients (us). Exhibitions, in turn, are simultaneously displays of her latest research and product launches.

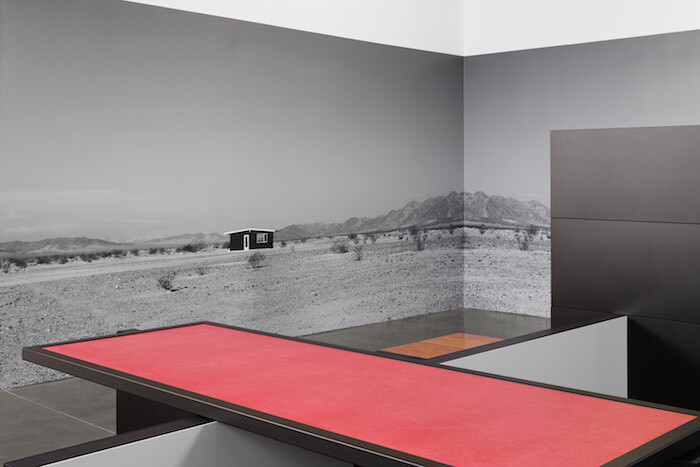

An enormous panoramic black-and-white photograph featuring a renovated pair of those Mojave Desert shacks wraps around two walls at Zittel’s current Andrea Rosen show. Although they might look inhospitable, Zittel has produced matching interior settings for them that are on display in the gallery. These two Planar Configurations (all works 2016) could be Constructivist sculptures, but in fact are a large table, a room divider, a bed frame, and a detached wooden floor meant to create a living space in which to cook, sleep, and recreate (which would appear to involve reading and working on a laptop computer). That these two units go in the photographed shacks isn’t obvious at first, but another large photograph high on the gallery wall shows a version of this modular interior installed in one of them.

Each Planar Configuration is sutured with a long vertical plane that would seem to limit the ability to reconfigure it. This is a key feature to much of Zittel’s practice: finding freedom within constraints, ones decided upon by the artist. Part of this freedom would seem to demand an element of depersonalization, almost a ridding of personality. Zittel’s abstract patternings and modes of assembly are certainly unique, yet there’s also an element of distance and formality to them, despite so frequently engaging with the intimacy of domestic spaces. Even the two Parallel Planar Panels hanging textiles whose stitched designs mimic the geometries of the modular units are intended to erect limits and divide rooms as opposed to adding interior warmth or decoration.

Zittel’s disassembling of the domestic has a clinical quality to it; it’s almost psychoanalytic in its relentless investigations of how home is imagined. Yet therein lies its liberatory appeal, both in stripping away habituation and attempting to reconceive how to live in a world tearing apart at the seams—socially, politically, environmentally. Very little feels left to chance in Zittel’s work; problems are made manageable. Hence, the fixity of the Planar Configurations, with their visible support structures, eliminates one set of uncertainties so that another can be confronted, possibly the more challenging one of what it means to be human. There’s also something almost comforting, although not quite cozy, in how every work in the show exists in twos, including the gouache and watercolor sketches for the units on display.

In the back gallery at Andrea Rosen, a wall-sized photograph shows a Planar Configuration in situ back in the Mojave, again connecting the exhibition’s two venues. Also installed in this room and at Zittel’s residence near Joshua Tree is a pair of Linear Sequences, which include a padded seat and two small cushions around a small, low table. It’s hard to envision these as sites for socializing or even extended relaxing. Humans don’t organize the space; space is meant to organize the human, which is another way of acknowledging the power of the desert landscape directly outside. Zittel makes sites within sites, which is a form of theater. The Planar Configurations and Linear Sequences in ways feel like stage sets, and the three photos of their installation are a documentation of their performance. This is social sculpture for domestic abodes situated in a harsh environment. That’s a metaphor, a psychological symptom, and totally real.