The evidence that we live in a dystopia is mostly swept out of sight, and kept out of mind. So let’s be clear that Trevor Paglen is engaged in a form of politically urgent visual labor. His work, most notably in photography, has given visual texture to a very real, and very menacing, shadow-realm. Lush, compelling images dramatize his near-failure to photograph post-9/11 black sites used for extraordinary rendition (quasi-legalized kidnap and torture of terror suspects); astral military satellites hard to make out in constellations of twinkling stars in the night sky; tiny drones seen from a distance, mosquito-like, crossing florid, sunset skies. Here are the enormous blind spots of our age, mostly off-screen zones that are routinely used to exercise and abuse power.

Presently Paglen is attentive to dismantling one of the most insidious metaphors of our age—that myth of immateriality which suggests that information is held and shared in data “clouds.” At the risk of victim-shaming myself and every other person with a smartphone, it’s true to say that societal blindness to infrastructure leaves us wide open to abuses of power. A failure to understand the geophysical elements of say, the internet (the mining of metals, the labor practices of tech, the physical nuts and bolts of servers, cables, and so on) has helped to usher in an era of already-entrenched surveillance.

Like several of his peers, the artist has been focusing on the physical make-up of the global digital-military complex (other notable examples include Lance Wakeling’s video work A Tour of the AC-1 Transatlantic Submarine Cable [2011]; Ben Schumacher’s recent sculptures including portions of telecommunications cables dredged from the ocean floor; John Gerrard’s videos of server farms; Tyler Coburn’s performances in data centers). But in a notional Venn diagram where those invested in the politics of emerging technology cross over with those involved in contemporary art, Paglen has perhaps become something of a ne plus ultra.In his second show at Metro Pictures, the artist continues this materialist line of inquiry, taking for a subject the enormous undersea telecommunication cables that carry data across the globe.

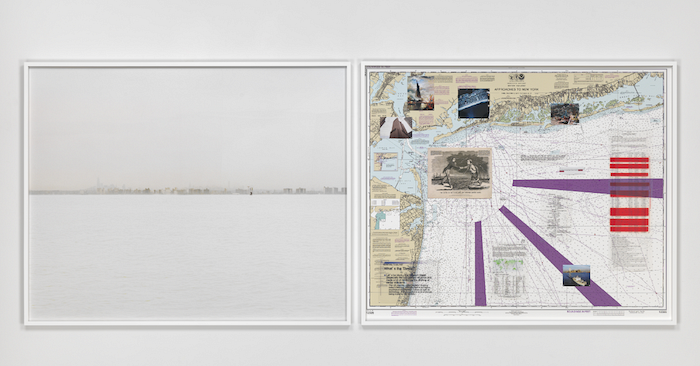

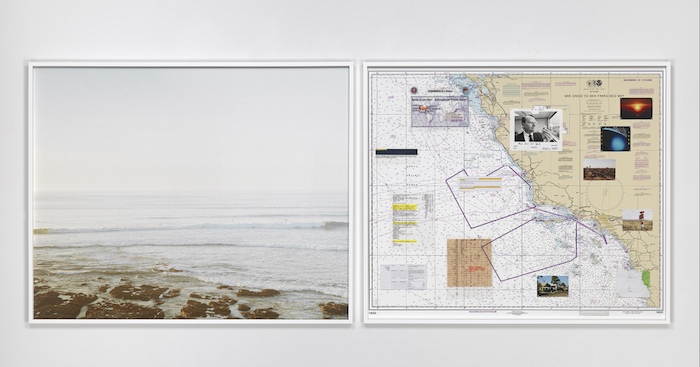

Paglen’s two diptych works at Metro—NSA-Tapped Fiber Optic Cable Landing Site, Morrow Bay, California, United States and NSA-Tapped Fiber Optic Cable Landing Site, New York City, New York, United States (both 2015)—picture “choke points” on the east and west coasts of America, where such cables land onshore and are vulnerable to tapping. On the left of each work is a pale, somewhat innocuous photograph of the coastal choke point location in question, resembling the omniscient disinterestedness of Richard Misrach’s seaside photographs more than anything else: nothing is ostensibly amiss. There are tiny surfers in California waves, and in New York the milky, chilly, Long Island coastline is strewn with buildings. On the right are collages: maritime maps of each coast overlaid with cable location details, historic material, and information from the Snowden leaks. Ominous, noirish textural details laid over the maps include NSA code names for AT&T and Verizon (“Fairview” and “Stormbrew” respectively) and notes on their compliance with regards to government surveillance, e.g.: “FAIRVIEW: … Aggressively involved in shaping traffic to run signals of interest past our monitors.”

In the name of human priorities, it seems somewhat irrelevant to criticize these works as art objects. As a reminder of what’s at stake: “[The NSA is] building the biggest weapon for oppression in the history of man, yet its directors exempt themselves from accountability” (email from Edward Snowden to Laura Poitras, 2013, quoted in Citizenfour (2015).1 However, that is what they are, and that is what I’m standing in this gallery for. And on that register, these works aren’t so great. They are rather polite, aestheticized carriers of information that seem as though they are trying to look like conceptual art from well over a decade ago: Tacita Dean without the narrative loopiness, Thomas Hirschhorn without the rabid junk—a kind of cleaned up version, actually, of all the stuff described in Hal Foster’s 2004 assessment of conceptual research tendencies “An Archival Impulse.”2 Unlike Paglen’s stronger works, these beg the question of whether this is all just brilliant rigorous journalistic research which has, for some reason, taken the form of an art object. Yes, it’s gladdening that certain forms of activism, political work, or digital communities have found a safe port in the art world (or a lucrative port, and this is arguably what happened with the gallery-bound transfer of internet/post-internet artists circa 2005-10). Still, this only works when it either transforms the material, or transforms the space around it.

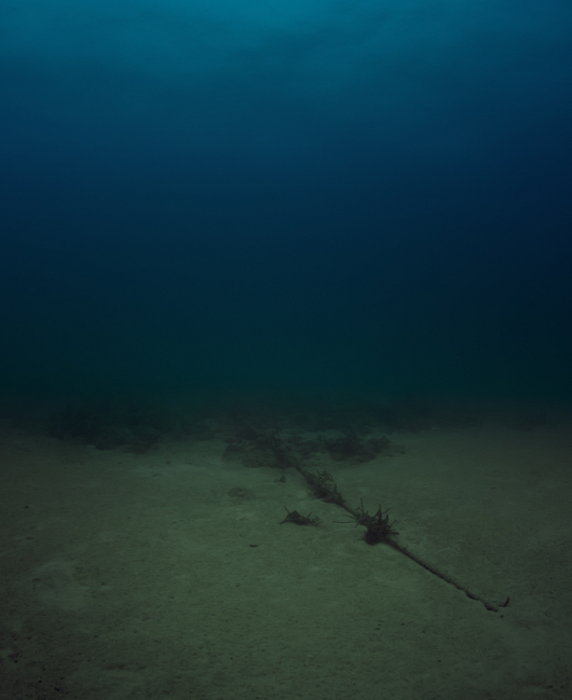

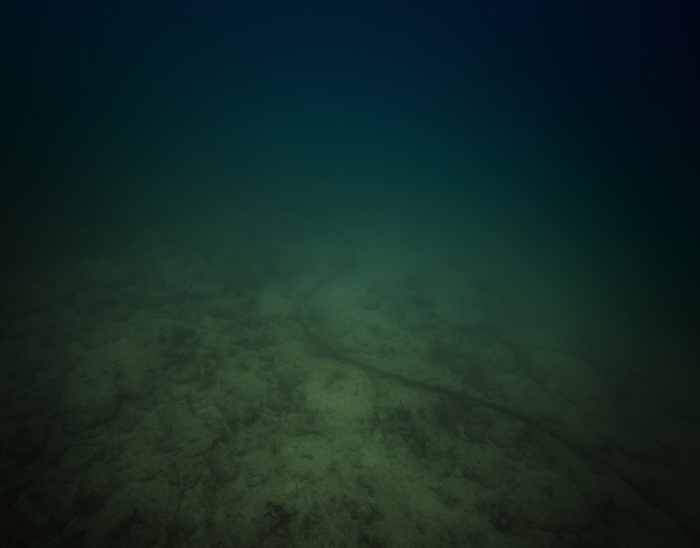

Closer to the aesthetic of Paglen’s previous skyscapes are his four photographs of the undersea cables themselves, large format C-prints that the artist captured after learning to scuba dive, Bahamas Internet Cable System (BICS-1) NSA/GCHQ-Tapped Undersea Cable Atlantic Ocean; Maya-1 NSA/CGHQ-Tapped Undersea Cable Caribbean Sea; Columbus III NSA/GCHQ-Tapped Undersea Cable Atlantic Ocean; and Globenet NSA/GCHQ-Tapped Undersea Cable Atlantic Ocean (all 2015). There they lie on the ocean floor, at the bottom of weighty waters running through shades of dark peacock, teal, petrol blue, and dull aquamarine. Stranger, and in fact more suggestive, texture is provided by Eighty Nine Landscapes (2015) a two-channel video installation in which codenames of NSA operations scroll by, connoting hints of infantilism, violence, machismo, peril, objecthood (a run through the last leg of the alphabet included RUFFLE FURBY, SCARLET HARLOT, SECOND DATE, SLEEPING BEAUTY, TURBO SNOW, VOLDEMORT). Another more decisive work is Autonomy Cube (2015), a clear plastic cube containing computers that provide a Wi-Fi connection that uses the Tor network, which anonymizes user data, providing a haven from surveillance. Joining it involves a kind of perceptive shift in which one acknowledges the openness and risk of other everyday interactions.

A final room shows unused panoramic footage of surveillance sites and apparatus that Paglen shot for Citizenfour (2014), accompanied by an ominous, atmospheric soundtrack. Occasionally, rather than a cluster of white pod buildings or anonymous government offices, the camera focuses on skies and waters—Paglen is, after all, something of a landscape artist. As silvery water shimmers mirror-like, reflecting the sky above, I thought of the similarly panoramic painting Le Bassin Aux Nymphéas (1919), Claude Monet’s long, three-panel painting of his lily pond, in which the depth of the painting shifts before your eyes, pulling you under the water, over the surface, and into the sky, with no steady place to rest. Paglen’s research and knowledge has this kind of vertigo to it, but these artworks, if they are to transform viewers, need to be transformed into something more unstable and unsettling themselves. It’s true that they have a format problem, and yet, in the name of human priorities, I still feel compelled to advocate for their existence.

Trevor Paglen’s footage of surveillance sites was included Laura Poitras’s Oscar-winning film Citizenfour (2014), which documents and explores Edward Snowden’s whistle-blowing revelations of mass government-authorized surveillance by the NSA and GCHQ.

Hal Foster, “An Archival Impulse,” October, No. 110 (Autumn 2004): 3–22.