It is lamentable and somewhat curious that John Akomfrah is just now receiving his first major exhibition in the US. Despite the critical acclaim Akomfrah has received in the UK and Europe, both for his recent solo output and his earlier work with the Black Audio Film Collective, he remains relatively unknown to Americans outside the experimental film community. One hopes that the current show at Lisson Gallery’s new Chelsea outpost will begin to address this oversight, thereby bringing more attention to the pivotal, underexposed history of Black British cultural production in the Thatcher era and to its continuing relevance in the present.

Responding to the precedent of Third Cinema, as well as the thinking of figures including Stuart Hall and Paul Gilroy, groups like BAFC and Sankofa Film and Video Collective (which included Isaac Julien) used broadcast media to advance a nuanced critique of the intersections between race, neoliberalism, and postcoloniality. Rethinking the politics of the African diaspora through the idiom of emergent artistic, musical, and mediatic forms, these cooperatives laid the foundation for what would later be called Afrofuturism, establishing a crucial precedent for contemporary practices like those of the Otolith Group and Chimurenga. Perhaps the most outstanding example from this field is BAFC’s 1986 Handsworth Songs, directed by Akomfrah, a singular and still searing essay film that analyzed British race riots through a charged fusion of archival footage, still photographs, and a “sound mosaic” that intermixed poetic voice-overs with the rhythms of dub reggae and free jazz.

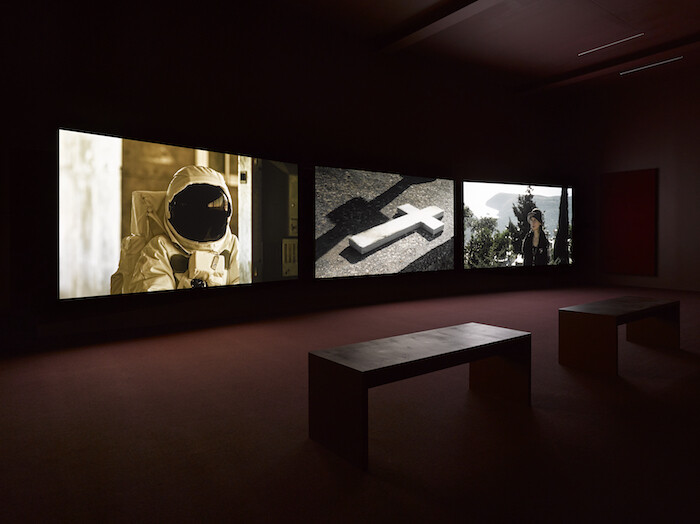

Given Brexit, the European refugee crisis, and the uprisings against racist police violence in the US, the contemporary resonance of such work is painfully clear, and the Lisson exhibition thus offers a welcome opportunity to make a case for Akomfrah’s importance. The show also gives a New York audience its first chance to evaluate the dramatic reorientation that has occurred in Akomfrah’s recent work, in films like Vertigo Sea (2015) and Tropikos (2016) as well as Auto Da Fé and The Airport (both 2016), the two pieces shown at Lisson. The most obvious change has been his move from collectively produced experimental documentaries for television or cinema to solo-authored (but jointly executed) multi-channel film installations for the gallery.

This shift of format, which necessarily entails a different audience and altered viewing conditions, has brought with it a number of formal adaptations. Juxtapositions occur not only within the frame but across screens. Production values have been conspicuously upscaled; the cinematography and mise en scène now approach the sort of art cinema associated with Steve McQueen or Wong Kar-wai. In a concession to the drop-in viewer, these pieces favor the long take and eschew any sort of linear narrative or argument, whether spoken or suggested. The overall result is something that resembles not documentary so much as silent film or dance. There is a much closer attention to the status of bodies, and to the way that posture and gesture can come to bear the weight of history and exile.

There remains much in these films to identify them as Akomfrah’s. The virtuosic sound design stands out: with its seamlessly edited cuts between lilting strains of calypso and abstract pulses of sub-bass, it implicitly compares the movement of peoples to the shifting of glaciers or the gusting of desert winds. Like Akomfrah’s recent filmic tributes to Stuart Hall (The Unfinished Conversation and The Stuart Hall Project, both 2013), these works display a keen, empathic interest in the interplay between the structural, macroscopic shifts that fuel migrations and the disparate ways that people register these changes through feeling, thought, art, and resistance. Whereas Akomfrah’s earlier work centered around the Black Atlantic, his frame has broadened both historically and geographically, such that it can now consider the relocation of Sephardic Jews from Brazil to Barbados in the 1600s alongside the ongoing flight of refugees from Iraq and Syria. In this light, the recurrent imagery of oceans in these films reads as an attempt to give redemptive form to these histories of exile, subjugation, and loss, transcoding them into something like a diasporic sublime.

As one might expect, this lyrical and rather oblique approach is a jarring departure from the much more militant and agitational character of Akomfrah’s work with BAFC. Despite the occasional reference to William Blake, those films and videos were firmly rooted in the twentieth century, drawing connections between Dziga Vertov and Santiago Álvarez, or between Sun Ra, P-Funk, and Goldie. By contrast, both Auto Da Fé and The Airport exhibit a strongly Romantic character in their fascination with desolation and ruin, falling back on a heavy-handed symbolism in their depictions of rain on gravestones, or vintage photographs being washed by waves. At times the style of these films even feels somewhat baroque, whether in the elaborate contrivances of their design or their reliance on mystery and allegory, which recalls the seventeenth-century German “mourning plays” analyzed by Walter Benjamin. There is indeed something strongly Benjaminian about this saturnine-redemptive view toward the past, and the central character of a wandering astronaut in The Airport begins to look a lot like Benjamin’s Angel of History, propelled helplessly into the future while surveying a history of ever-accumulating ruin.

Confronted with this work, the incumbent critical question is what to make of such a marked shift. Perhaps the best thing one can say in Akomfrah’s defense is that his recent films are powerfully arresting, in both senses of the term. They are consistently and intensely beautiful, saturated with feeling and unexpectedly vivid detail; one watches them and quietly aches. At the same time, they work against the viewer’s expectations of how temporality functions: time slips, skips, and sometimes seems to halt altogether. Melancholy blends into reverie, and the distinctions blur between film, photography, and tableau vivant. At their most ambitious and successful, the films represent an attempt to imagine the ways that diasporic histories inform the present at the affective level in our very experience of space and time.

With this said, one is reminded of Theodor Adorno’s famous remark that Benjamin’s dialectic lacked a certain mediation.1 Akomfrah’s recent films, though occasionally brilliant, feel like essay films without the essay. Almost every image seems perfect, in its own way, and yet the films as a whole have a listless or even lethargic character. The most sympathetic explanation for this problem is that Akomfrah is trying to balance analysis with abstraction while negotiating the challenges of a new format. A more skeptical take would be that such issues follow from the decision to address an international art audience, one that craves a certain topicality but might not have the time, patience, or linguistic facility to engage more demanding work.

It is both praise and criticism to say that both Auto Da Fé and The Airport come off like first-rate biennial art. If they manage to address quasi-universal themes through the rhetoric of global contemporary art, they also do little to challenge the hegemonic or narcissistic tendencies of privileged liberal humanitarianism. Surprisingly, and rather regrettably, these films fail to address basic problems of representation. Their lack of dialogue means that their subjects, whether historical or contemporary, are never allowed to speak; since we have no other way of effectively accessing their inner lives, it is as if they can’t even really think for themselves. The lack of attention to historical specificity, while intended to enable a kind of speculative time travel, results in highly problematic conflations: between the concrete particulars of historically contingent politico-economic conjunctures, and between the analogous but distinct conditions of the refugee, the exile, and the migrant. At their most manipulative—as in Auto Da Fé’s images of a doll washed ashore and its dedication to Aylan Kurdi—these films descend into a kind of humanitarian kitsch, much like the widely derided recent work of Ai Weiwei. Given the scale and scope of current crises, it seems fair to ask more from artists as thoughtful and capable as Akomfrah. This moment needs its own version of Handsworth Songs; one hopes Akomfrah will go on to make it.

“Exchange with Adorno on ‘Paris of the Second Empire’,” in Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings: 1938-40, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003), 101