Our contemporary ontology is one of acceleration and mania. Along with the logic of global and cognitive capitalism, we look to our iPhones and the internet as the source for these intensified temporalities. Indeed, walk out on any street and hundreds of individuals are engaged in locating their sense of self and place via the rapid click of the cell-phone snapshot. Jean-Luc Mylayne’s 38-year oeuvre of patiently staged conceptual nature photography is the philosophical inversion of this state. Famous for his extensive labor and Zen-like patience, not to mention the huge amounts of time and ethical sensitivity he invests in creating his images of birds (as if that is all he is doing), Mylayne has more in common with Proust’s distended moments of reflective memory than the manic attention deficit of today’s amnesiac iPhone present. In fact, while preeminently photographic, his work calls more upon the fixed, contemplative gaze of modernist cinema and Bergsonian duration than upon the gee-whiz gimmickry of still digital photography. And yet Mylayne has also been linked to a new ethics of animal studies, since his work depends upon trust and mutual recognition, not force or artificial hierarchies of human versus animal. These “bird photographs” are much more than indexes, as Fiona Mann states in her essay “Angel of Repose”— “for Mylayne’s pursuit is, in the end, a register of ontological awareness.”1

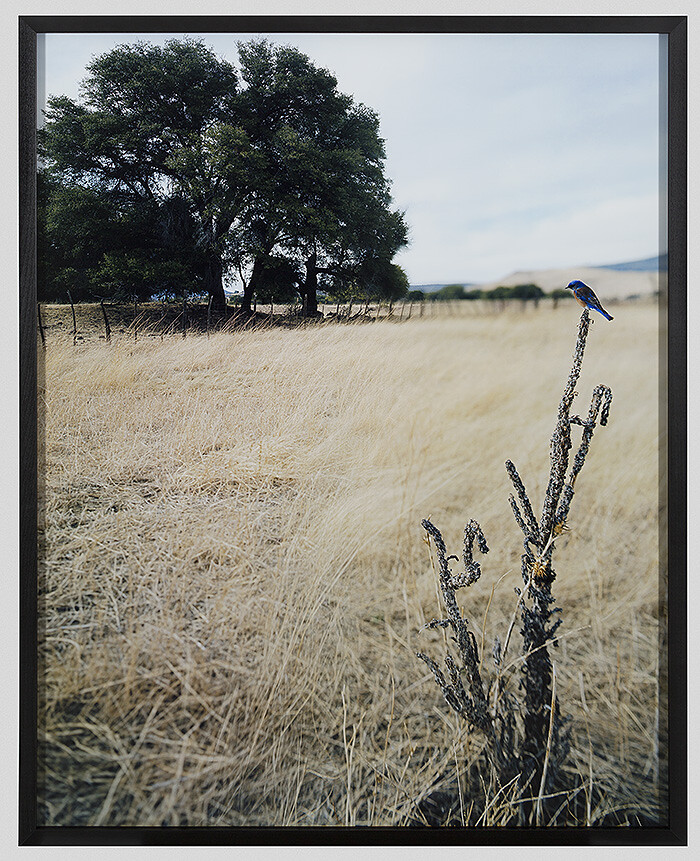

“Chaos” raises this call for awareness through themes of the vanishing and vulnerability of birds (here, bluebirds), susceptible as they are to their environment and surprisingly brief lifespans (unlike parrots who can live to 80, most bluebirds don’t make it to one year). Selected from his relatively small collection of works—considering he started photographing in 1976, yet in 2000 had only 150 prints—“Chaos” is a collection of nine C-prints numbered and dated by month, and almost all are from January and February of the years 2004, 2006, 2007, and 2008.

The exhibition begins in the main gallery with a series of portraits of the same scene, each taken at a different time of day, from January to February of 2004. In each, a line of tiny bluebirds balances delicately on the rim of a wooden barrel filled with water, set against the backdrop of a rural landscape. Framed so the horizontal line of birds, rim, and water stretch along the base of each photograph, the greater part of these six-foot vertical frames is filled with the overwhelming block of color of the metamorphosing natural sky. As the colors change, so does the time of day, reminding us how time is, in the words of poet Robert Kelly, “a lie/that color tries to heal us from.”2

From late day, to sunset, to dark night, these works depict the effect of the earth’s 24-hour rotation on the planet, as a color wheel sky, weighty in its presence, transforming from blue to black. In No. 195, Janvier Février 2004 (2004), the azure sky overwhelms the tiny cornflower bluebird bodies which stand out in contrast to the mottled ecru of the wooden rim. The water below mirrors the azure of the sky. In No. 191, Janvier Février 2004 (2004), the sky is blue-black and the water a steely moonlit blue-gray. In each, the bluebirds are merely dots of varying blues (like the variations on a paint chip sample), actors in the drama of nature and culture, which Mylayne never sets up as an opposition. In other words, “birds” are never a simple symbol of arcadia inhabiting a zone of innocence outside of culture. Indeed, it is Mylayne who uses the word “actor” to describe the birds he photographs, as if to say: remember this is culture I am interacting with.

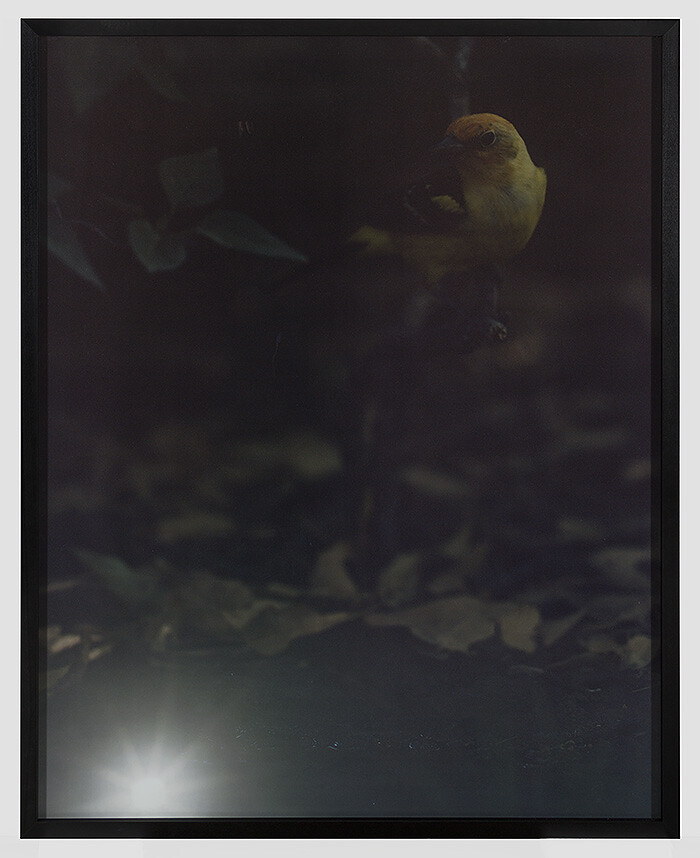

As one circulates through the gallery, the call to awareness increases. No. 401 Avril Mai 2006 (2006)— ironically the one photograph taken in spring—is dark. We can barely make out the trace silhouette of a bird in a tree taken at night. This is an unusual photograph for Mylayne. It is absent of context—landscape—and the bird is shot in close up so as to fill most of the frame. The aura of the photograph is one of death as claustrophobic inevitability. In contrast, isolated in the project room around the corner, No. 560 Janvier Février 2008 (2008) portrays the explosive time lapse shuddering white blur of wings in motion, set against the backdrop of a barren tree and piercing blue sky. Unlike most of the others, it is spliced and layered from a series of images. Mylayne does not hide the shifts in temporality when he layers the images, but exaggerates them, so that tree and bird stutter in haunting bands of temporal and visual rhythm. Abstract and exhilarating, it is the showpiece of the exhibition, the very embodiment of the color of time as a drive towards entropy.

Flawed only by the annoying reflection of oneself or others, due to the lighting and surface reflection of the works in the gallery, “Chaos” is ultimately an operatic encounter, a soulful proto-cinematic allegory of birds in time and as time; a whisper in our ear to be sensitive to our ontological awareness of the winged blink that constitutes this blur we call life.

Fiona Mann, “Angel of Repose,” Parkett, no. 85 (2009): 56.

Robert Kelly, The Color Mill: An image/poetry collaboration between poet Robert Kelly and artist Nathlie Provosty (Brooklyn: Spuyten Duyvil, 2014).