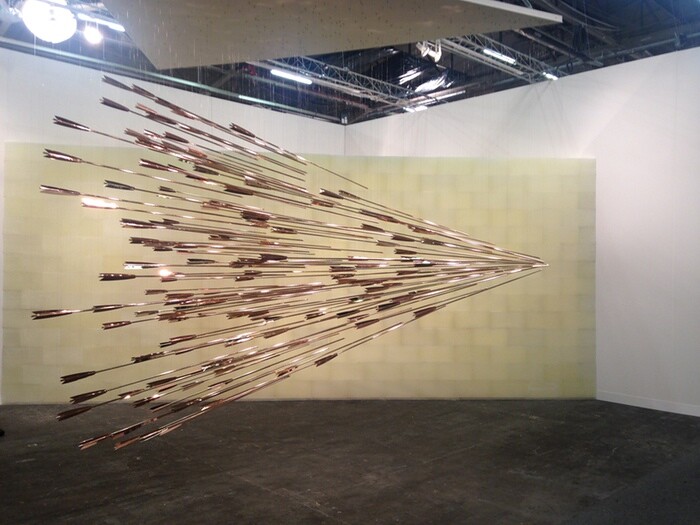

Trendspotting is a competitive sport at art fairs. Still, with every fashion, there’s always an artist who either reinvents worn forms or executes them so well it’s hard not to admire. This year, it’s the case of objects hanging from fishing lines—a frequent fair staple—and Glenn Kaino’s A Shout Within a Storm (2014) on view at Los Angeles’s Honor Fraser is the perfect example. The 149 copper-plated steel arrows, shining in the strong exhibition lighting, filled the booth, especially since Kaino’s paraffin brick wall, The Last Sight of Icarus (2014), was positioned diagonally against the back corner, pressing the space even further. They’re not site-specific, but seeing them together at a fair—where they seem monumental and ambitious in comparison to all the paintings hanging on drywall—becomes not only impressive, but also meaningful. When sameness abounds, it’s key to focus on the work that’s different.

At Philipp von Rosen Galerie, Cologne, Anna K.E. showed Post-Hunger Generation (2015), comprising drawings on paper installed in a wooden structure. The architectural configuration served to frame the drawings and a small monitor, showing a man’s hands as he unwraps plastic packages and rearranges their contents (headphones, an SD card, a USB cable) on a table, to the sound of a violin and the crackling of the plastic. It’s a smart piece that—unlike so much work at a fair, which looks polished and ready to sell—delineates process. Which is also the topic of Jorge Méndez Blake’s From an Unfinished Work (The Garden of Eden) (2014), 85 aluminum-made crumpled papers printed with the text from Ernest Hemingway’s posthumous novel The Garden of Eden (trend alert: lots of work about/including literature and pages from books everywhere at both Armory and Independent) at 1301PE from Los Angeles. Ettore Spalletti’s gold-leaf-brimmed panel La luce e il colore, azzuro tenue (2012) also fed off the strong lighting at the fair—so much so that it seemed to float off the temporary walls as light hit the gold. And the simple, even simplistic, gesture of cutting out extinct species from pages of natural history books by Brandon Ballengée in his installation The Frameworks of Absence (2006–ongoing) at Ronald Feldman, New York also gained traction just by being at the fair, exhibited in a booth painted deep red, reminiscent of a nineteenth-century museum.

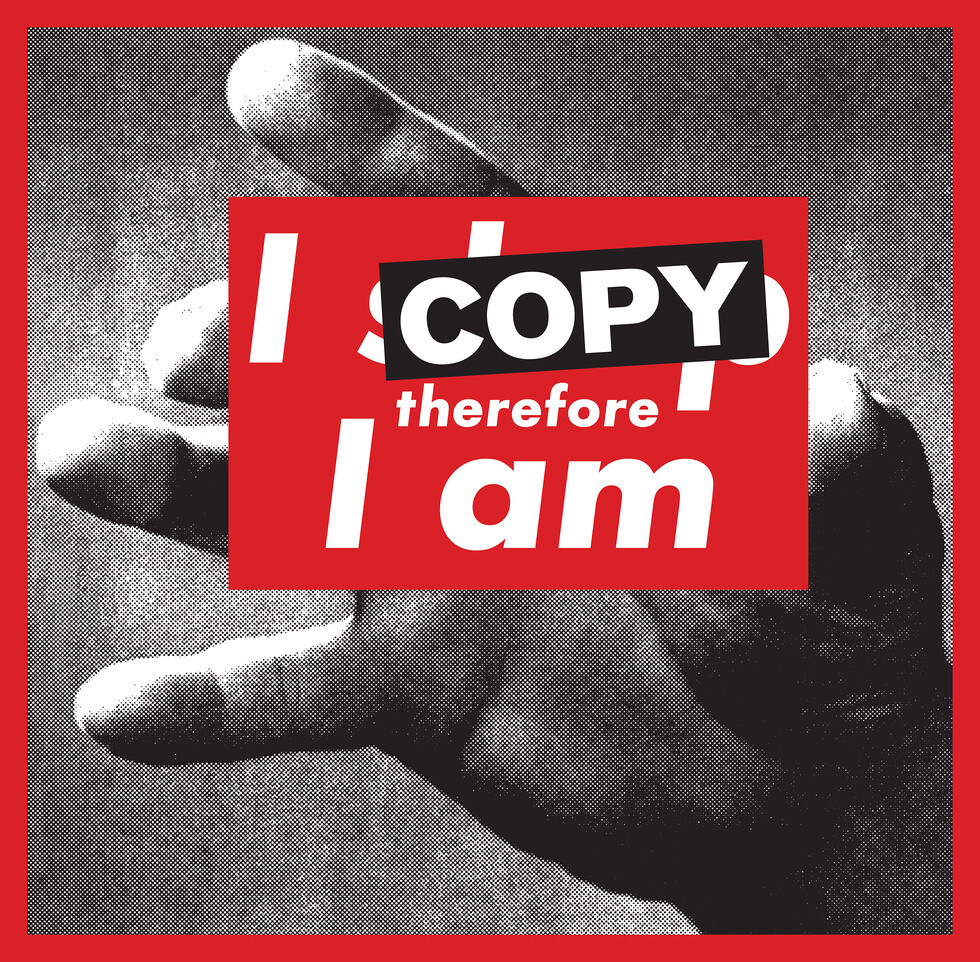

Speaking of the nineteenth century, another trend: a number of works on view at Armory play with direct references to art history. There’s a marble bust (Ingleby Gallery from Edinburgh shows an untitled 2014 piece by Jonathan Owens, where the materials list says it all: “carved nineteenth-century marble bust, with further carving”); a Donald Judd which is actually I Am Broken (2011), a piece Ryan Gander compiled from Ikea shelves, at Johnen Galerie, Berlin; a two-in-one homage to Vladimir Tatlin and Dan Flavin (Bettine Pousttchi’s Double Monument for Flavin and Tatlin XII [2013] at Buchmann Galerie, Berlin, made of a neon tube twisted barriers, the kind used in the streets to control crowds); and a work from Superflex at Los Angeles’s 1301PE which takes on Barbara Kruger’s Untitled (I shop therefore I am) (1987), but has the word COPY pasted to cover “shop,” shifting the meaning of Kruger’s piece to a statement about an updated form of resisting consumer culture: digital copying. These works show artists reconsidering older forms and the way they are applicable in contemporary society, as well as how they can be used as material (both physical and intellectual) with which to work. But it’s also a quick, direct way of creating value: making reference to recognizable work, whose worth has already been asserted.

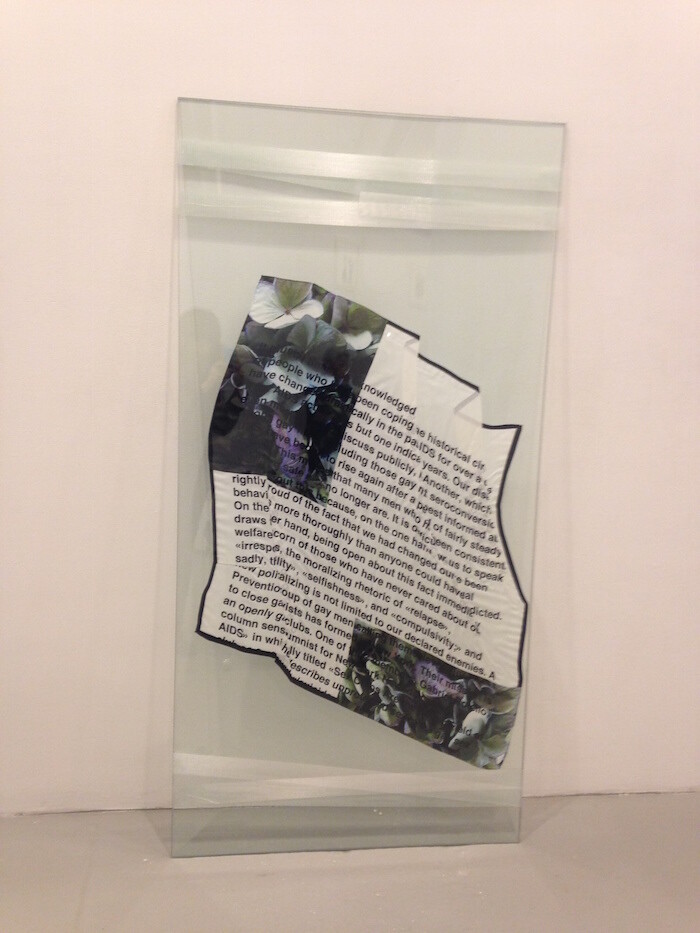

Unlike the Armory Show, which can look like any other fair, Independent, with its open floor plan, always feels different. There is lots of painting here, too, but also much more nuanced work, especially among the galleries who presented single-artist booths. Emanuel Layr, from Vienna, is showing My Epidemic (2015), new works from Lili Reynaud-Dewar: a video of the artist dancing, naked, in an empty palazzo in Venice and next to it a table full of silk scarves printed with images from Reynaud-Dewar’s previous performances, and a collection of excerpted texts on sexuality, publicness, queer theory, and the AIDS crisis. The precious, feminine fabric becomes reading material provoking the viewer to consider her or his vulnerable position when faced with the directness of this artist’s work. Not far away is a vinyl sign on the floor reading “viewer discretion advised: graphic sexual imagery.” Brazilian gallery Mendes Wood has brought the work of f.marquespenteado, and it is a little difficult to look at: behind a woven plastic curtain is a matching game of sorts, between dictionary definitions of prison speak—“booty check,” “butched in” (don’t google these)—and quick drawings on fabric depicting these activities. It checks your alliances, borders, and politics. And it’s shocking, especially in light of the artist’s other works on view, compositions on linen that are hardly sinister. At times it’s too blatant when galleries bring more sellable work to accompany installations at fairs, but in this case it allows the viewer a better understanding of the artist’s depth, and a much-needed break from more graphic work. David Kordansky from Los Angeles gave over his booth to Andrea Büttner, who designed everything from the walls (Brown Wall Painting, 2006) to the bench in the middle (Benches [corner seat], 2010, a wooden top over gray milk crates).

Though Independent’s open plan looks deceivingly like an exhibition (albeit a messy one), there’s something comforting about the fairs not being “curated,” which allows visitors to pay attention to the work, rather than an overarching theme (which here would be the role of the market in contemporary artistic production). The exception is Armory’s Focus section, which is curated to prioritize a different region every year. This time it is Whitechapel Gallery curator Omar Kholeif, who selected galleries from the Middle East and Mediterranean. While not all galleries were of equal quality (and it seems unavoidable in this kind of section not to see a number of globe- or map-based works, see Fayçal Baghriche’s Souvenir [2012] at Taymour Grahne, New York), some projects originating from this section were memorable: Darvish Fakr’s Flying Carpet (2015), on which he hovered through the fair during opening day, conflating some classic, exoticizing imagery of the Middle East with its current reality (reality check: I saw the carpet charging at a plug socket at his London gallery, EOA Projects); Oraib Toukan’s 2007 The New(er) Middle East, a broken-up magnetized map of the Middle East, where the viewer could rearrange the countries as they wished, and Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s commissioned project, A Convention of Tiny Movements (2015). Part of it (there’s also an audio essay) is 5000 bags of potato chips distributed through the fair. The back is printed with a text about computer scientists at MIT who developed a system that can, by reading the small vibrations in any given object, recover the sounds that produced them. It means that any object can become a listening device, including any of the bags of chips produced for the fair. As I write this, the (ahem, empty) bag of chips beside me on my desk, I’m reminded—in case I forgot amidst all those paintings—that a small intervention in the tried-and-tested structure of the art fair can once again turn everything political. Of course it’s possible to see art at a fair and think through surveillance, larger political structures, and economics beyond just those of the art world.