Bruce Conner used to give fits to museums and galleries. He exasperated William C. Seitz when he served as his consultant for the landmark 1961 exhibition “The Art of Assemblage” at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, which culminated in the artist dumping a box of junk at the doorway during the show’s opening (an attempt to demonstrate to the curator what “real” assemblage was). In 1964, he fatally poisoned his working relationship with his longtime New York gallerist Charles Alan by handing him a box of random objects to show in lieu of new work. And, in the 1970s, with an idea well ahead of its time, he insisted on a cut of the “box office” for a planned mid-career retrospective at what is now the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.1 (He was deadly serious, and his intransigence ultimately scuttled the show.) Conner died in 2008, but it is fun to imagine what new aggravation, were he still around, he might inflict on those currently planning his major retrospective, jointly organized by MoMA and SFMOMA and set to open in July 2016. In the meantime, Paula Cooper Gallery offers an elegant if rather solemn show of Conner’s work in a range of media, the cerebral emphasis of which cannot quite tame the more anarchic impulses of its mischievous subject.

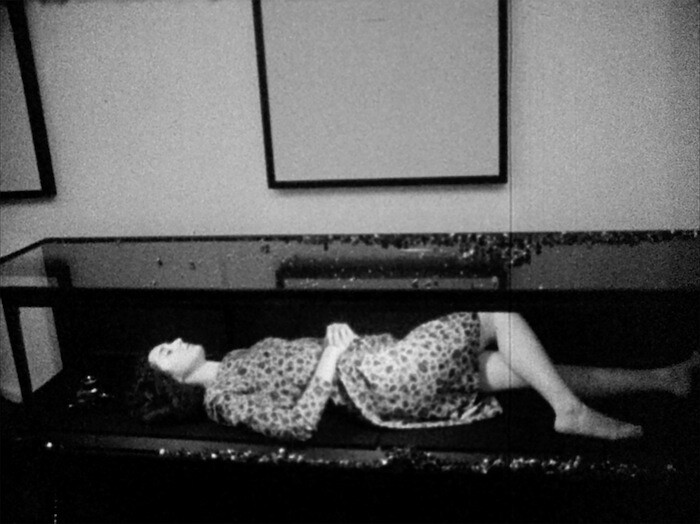

The intimacy of Cooper’s second-floor gallery in Chelsea suits Conner, as it recalls the cozy, funky San Francisco spaces that showed the artist for most of a career that began in the late 1950s. One of those spaces is brought uncannily to life here by way of the three-minute film VIVIAN (1964), screened on continuous loop (regrettably, but understandably, on digital video rather than 16mm). For the film, Conner trained his Bolex on his friend Vivian Kurz, who posed, preened, and danced her way through San Francisco’s way-out-there Batman Gallery during a 1964 exhibition of his work. (Conway Twitty’s antic version of “Mona Lisa” provides the soundtrack.) That show was a riot: open 24 hours a day for 3 days, it included not only assemblages and paintings but also a suitcase filled with thousands of marbles that found their way into everything during the show, including a giant, coffin-like glass case. (“It was there for women to go in, basically,” Conner said at the time.)2 One salutary effect of Conner’s currently rising stock is that as he becomes more familiar, his work is allowed to be less so: fewer assemblages, non-canonical films. VIVIAN is one of Conner’s lesser-known movies, and it is a treat to see. It also eerily reanimates the work on view in the two other rooms, which date from the 1950s through the 1990s. (The one assemblage present—a pair of shoes painted, beaded, bound together, and hung from a string—appears prominently in the film.)

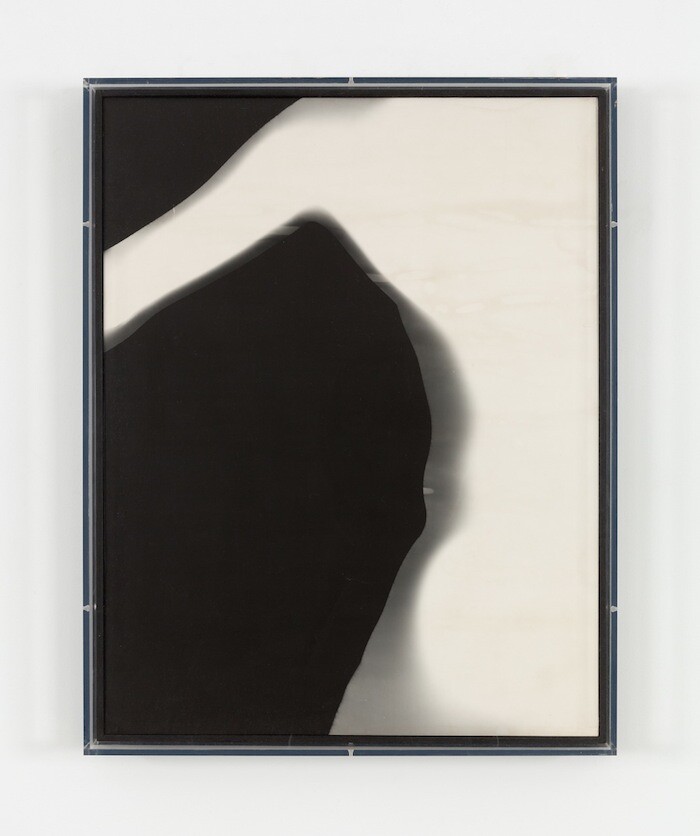

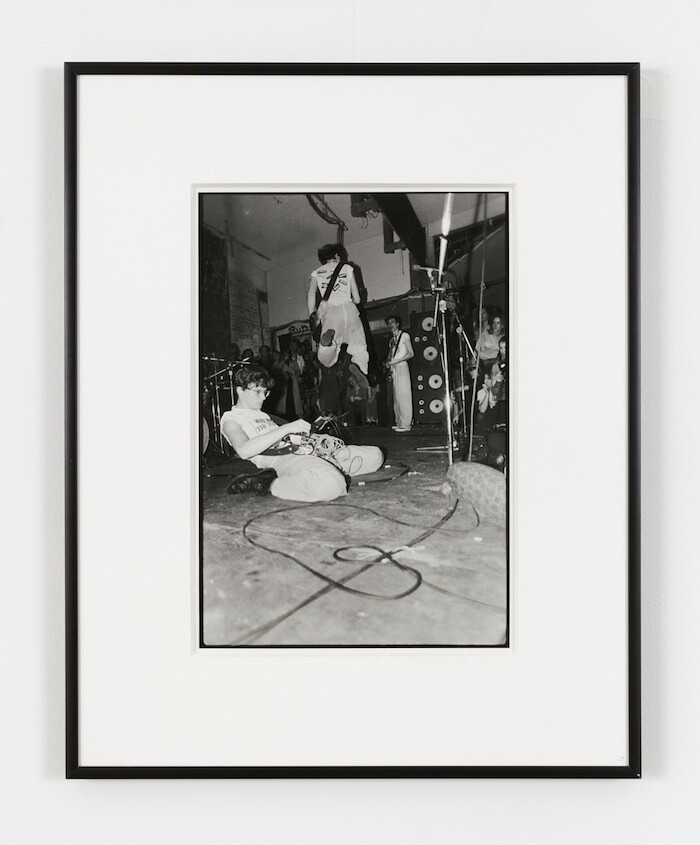

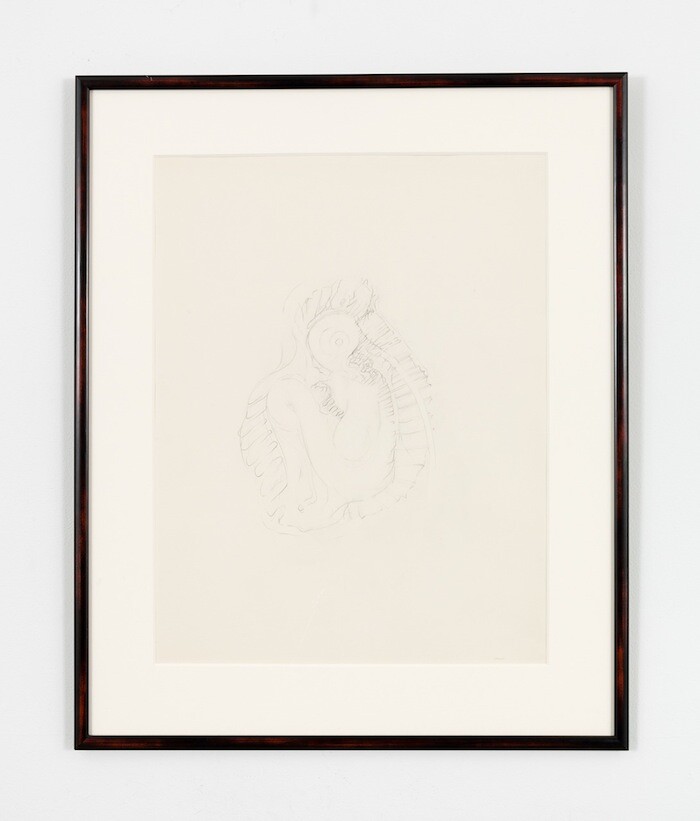

According to the press release, the drawings, collages, and photographs on view focus on the human figure. Yet perhaps the more significant through-line is Conner’s sense of occult spiritualism, which, in its earnestness, remains as much of an awkward fit in Chelsea today as it was in the irony-heavy postwar American art world out of which he emerged. The tendency is present in GERYON, JULY 31, 1955 (1955), the earliest work on view, a remarkable suite of dense ink drawings of the Dantean monster Geryon, the embodiment of Fraud in the Inferno, whom Conner, barely out of his teens, treated straight-facedly as a powerfully hieratic talisman. The occult remained a potent force for Conner throughout his career and inflected his work in unexpected ways: two photograms that register the artist’s body in ghostly off-white—titled DEPARTING ANGEL and BOWING ANGEL (both 1973)—bring to mind nineteenth-century spirit photography, while barely-there pencil drawings, many from a year-long Mexican sojourn, render processes of human growth and mutation into otherworldly, peyote-tempered visions. Undercutting all the metaphysics, however, is “PUNK PHOTOS” (1978), a set of gritty photographs taken in 1978 that document punk shows then taking place at an outmoded Filipino cabaret called Mabuhay Gardens. (The venue became legendary, hosting everyone from Devo and Negative Trend to raucous bands that would last a single night.) While the photos capture their fair share of transcendent moments, their inclusion is a reminder that, for Conner, the spiritual is always cut with the comically ordinary.

The pairing of VIVIAN with the punk photos is inspired: separated by over two decades and different media, they underline how consistently Conner was drawn to the theatrical (his engraving collages, several of which are on view, often suggest characters populating stage sets). More pointedly, however, both hint at darker, difficult-to-control desires—the photographs explicitly in their athletic violence, VIVIAN implicitly in the objectification of its young female protagonist. (Near the end of the film, Conner fleetingly appears in the frame, looming threateningly over Kurz in the glass box.) Even if this quiet, serious show downplays the Dionysian, it nonetheless lurks at the edges—right where Conner would have wanted it.

At the time, the San Francisco Museum of Art; “Modern” was added to the institution’s name in 1975.

Bruce Conner, “Post-screening discussion with the audience at the 1968 Flaherty Seminar,” Film Comment 5, no. 4 (Winter 1969): 20.