This column aims to introduce and analyze the activity of a number of gallerists and galleries. I am interested in presenting not necessarily the history of major galleries and their successful careers, but to reflect on a series of experimental approaches to the gallery format, and to discuss the different modalities in which the borders of the profession of the gallerist and the format of the commercial gallery have been tested and eventually eroded. The first episode (which discussed Fabio Sargentini and his gallery, L’Attico, in Rome) analyzed the case of a dealer who had a strong curatorial approach to his gallery program and to the exhibition format, to the point of using the gallery as his own linguistic, even artistic, tool. In this second installment, I will discuss the activities of artist Kazuko Miyamoto and her role as an early member of A.I.R. Gallery (Artist In Residence Gallery) and as the founder and director of Gallery Onetwentyeight, both located in New York.

Born in Tokyo in 1942, where she studied art at the Gendai Bijutsu Kenkyujo (Contemporary Art Research Studio), Miyamoto moved to New York in 1964 to attend The Arts Student League of New York, located in Manhattan (1964–1968). During those years she supported herself by working in various cafés, bars, and restaurants, where she met many of the main figures of the Minimalist art movement in the city’s music and art scene of the time. In 1968 she got her first studio, located on the Lower East Side, at 117 Hester Street, in the same building where Sol LeWitt and Adrian Piper had their studios. Miyamoto became LeWitt’s first assistant and, for several years, she was involved in the production of many open-cube sculptures and the execution of some of his early wall drawings, engaging in a continuous dialogue fueled by mutual respect (Sol LeWitt’s collection still owns the largest number of Miyamoto’s works).

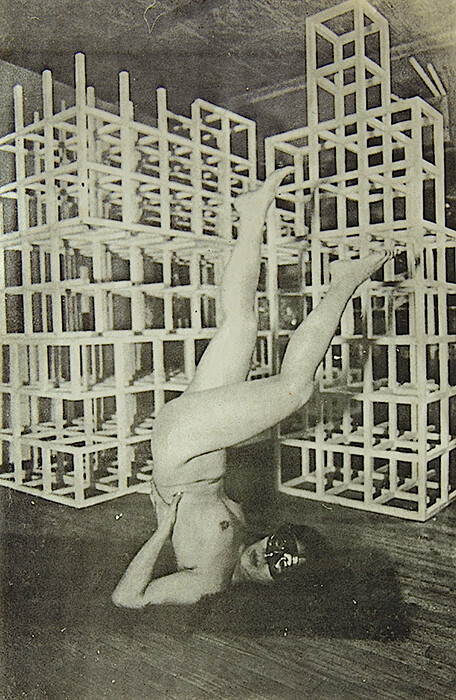

Parallel to her activity as LeWitt’s assistant, and probably under his influence, Miyamoto abandoned the expressionist character of her student days in Tokyo, engaging instead with Minimalist and post-Minimalist vocabularies. Her paintings (1968–72) and modular sculptures (1972–75) use an abstract geometrical language, adopting grids, modules, and patterns as recurring motifs while inserting some significant alterations. If materials such as charcoal and spray paint on canvas introduce a sense of imprecision and an organic element into the minimal grid—while including personal and cultural references to her Japanese background1—the modular sculptures are open forms that can be dismantled and presented in different configurations, as if they were toys to play with. Miyamoto’s works of that period can be read as a subtle, at-times ironic attack on the confident and masculine personality of Minimalist art.

This wasn’t certainly the only battle launched by women artists of the time. The New York art scene of the late 1960s and early 1970s witnessed a growing critical awareness and political engagement by female artists, articulated in two directions: as a series of radical, guerrilla-like actions against the art institutions that discriminated against women artists and minority groups in their programs, and through art practices that addressed the position of the female artist within a patriarchal society and art world. From 1969 onward a number of collectives, including the Art Workers Coalition, which formed in January of that year, initiated protests against the art world’s lack of consideration for the representation of minorities, namely the low percentage of female and black artists in the exhibitions and permanent collections of institutions, the discrimination suffered by women employed in art magazines and museums, as well as the sexist content in the teachings of art history.2 The most sensational of these protests targeted the MoMA and the Whitney Museum of American Art between 1970 and 1973. Protesters not only sent a letter to the Whitney Museum demanding that 50 percent of the artists in the exhibition should be women, but they also staged artists’ demonstrations and sit-ins during the two and half months leading up to the opening of the Whitney Annual exhibition. These protests soon led to some important concessions and changes in the policies of the institutions, for example in the number of female artists invited to the Whitney Annual.

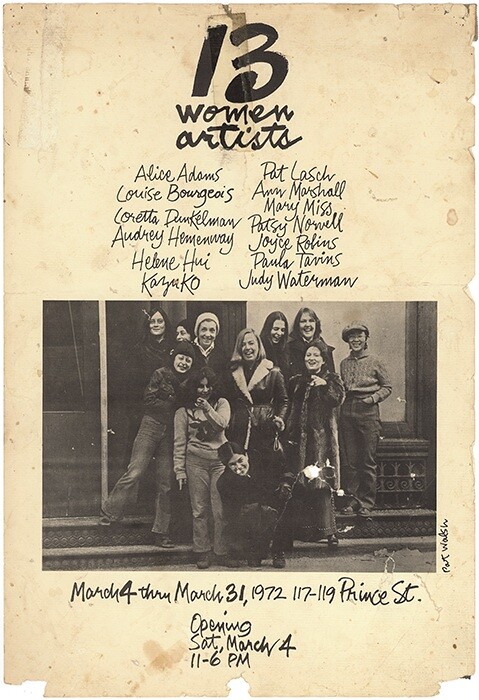

Female artists initiated a series of exhibitions and collective organizations engaged in sustaining and promoting their practices, which found little visibility in galleries and institutions. The exhibition “13 Women Artists,” held in March 1972 in a rented space in SoHo, was one of the first artistic expressions of this new awareness and solidarity. Miyamoto took part in the show alongside Louise Bourgeois, Loretta Dunkelman, Pat Lasch, and Patsy Norvell. The show constituted a kind of incubator for the birth of A.I.R. Gallery, which opened later that year, in September. If Susan Williams and Barbara Zucker were its initiators, they were soon joined by another small group (including Nancy Spero, already part of the above-mentioned Art Workers Coalition). After a careful process of selection, carried out using the slide registry of the Ad Hoc Women’s Artist Committee—an archive initiated in 1970 by Lucy Lippard, which gathered documentation of the work of about 600 women artists—the original nucleus grew to 20 members, including Dunkelman and Norvell. Together, the founding members renovated the first gallery space at 97 Wooster Street and established the gallery’s guiding policies: A.I.R. had no director and no leader; each member had a part in collective decision-making in monthly meetings; each artist had to contribute a certain amount of their own money and collaborate on the practical aspects of the organization and maintenance of the gallery. In return, members had the right to have a solo exhibition every two years, in which they had total autonomy. The entire profit of each sold work went to the artist, thus bypassing the usual 50 percent commission to the dealer.

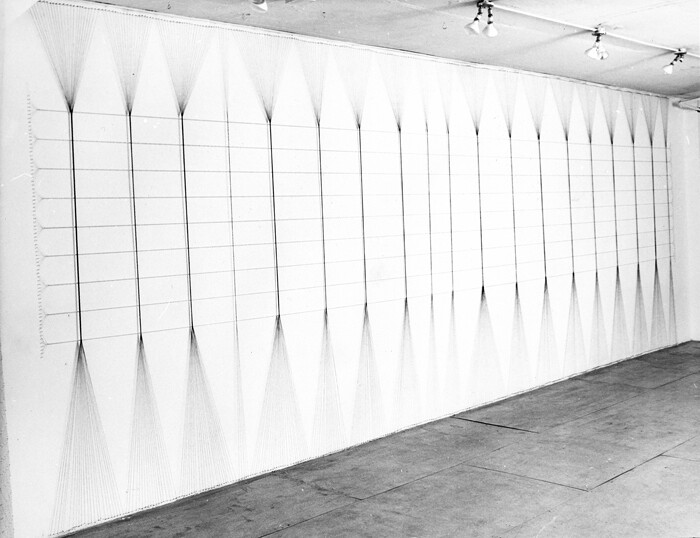

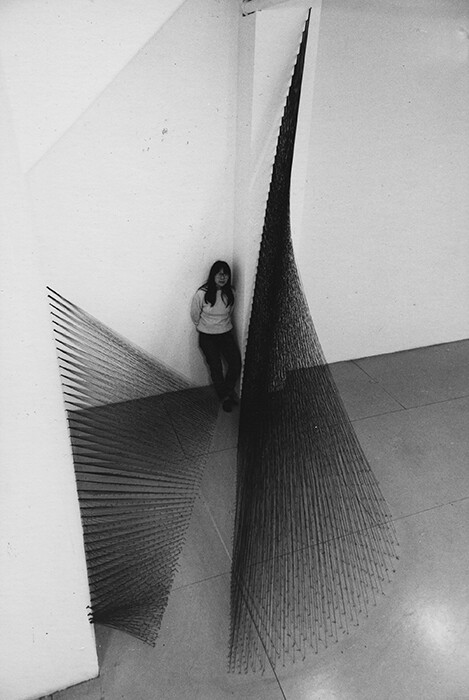

Miyamoto was not part of this initial group, but she was invited to join it in 1974. During her almost ten years of affiliation with A.I.R., she presented five solo shows and co-organized two group exhibitions. It’s possible to follow a significant thread in her artistic trajectory through her solo exhibitions at A.I.R. As early as 1972, while she was still working on modular objects, Miyamoto started to experiment with nailing industrial cotton strings to walls in order to create site-specific interventions with a bi-dimensional quality, which became increasingly complex. Different configurations occupied the walls of the MoMA penthouse (Untitled, 1973), of John Weber gallery (Untitled, 1975) and PS1 (Egypt, 1978). Also around 1972, Miyamoto started to use strings and nails in a tri-dimensional fashion, designing different indefinable figures that occupied a volume at the intersection of the wall and the floor (“String Constructions”). As critic Lawrence Alloway noted, Miyamoto “pursued, with relentless subtlety, a three-dimensional potential implicit in the drawings but not realized by LeWitt.”3 More specifically, the “ambiguous” character of these works is compelling: with the spatial nature of an installation, the optical quality of a kinetic work, and the durational character of a long performance, “String Constructions” are based on a dialogue between the body and the physical context in which the sculptures are installed—a temporal and ephemeral occupation of space using the lightest and most modest of materials. The result of a time-consuming process of doing and undoing, like that of Penelope, these works avoid the mechanical, industrial, and hard-edge forms typical of Minimalism and underline the importance of time and manual labor in the production process, in strict dialogue with techniques traditionally linked to female forms of work.4

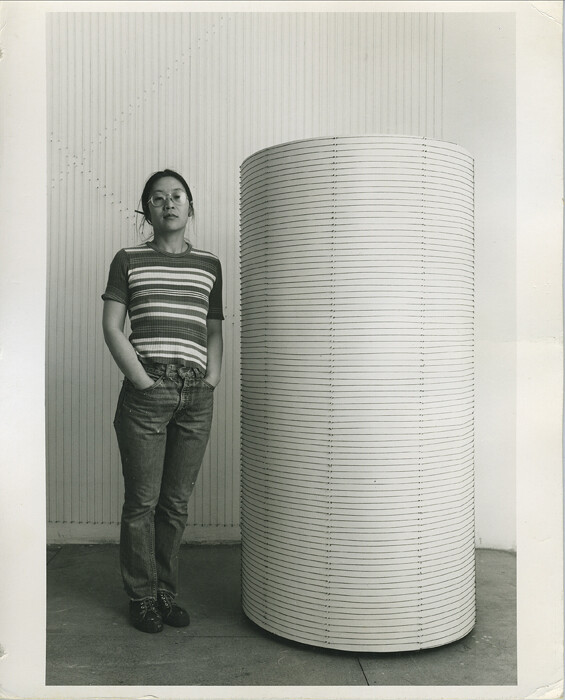

Different “String Constructions” were presented at A.I.R. Gallery on a number of occasions between 1975 and 1983. In her 1979 show, Miyamoto invited the experimental dancer Yoshiko Chuma to relate to her work and perform around her installations, thus demonstrating the crucial role played by the body in conceiving these works and in Miyamoto’s overall practice.5 This relation to the body was already evident in her previous solo show at A.I.R. (1977), where she built up two cylinders that measured the exact height of her and her then-partner’s body, covering them with a pattern of strings and nails, thus giving the Minimalist shape a personal, even intimate character.6

With a 1980 exhibition at A.I.R. (“Nesting”), Miyamoto liberated her work from any residual constraint inherited from the language of Minimalism, giving it a more organic and environmental character. Using natural elements, such as birches and leaves, alongside paper and ropes, she fabricated objects and installations that could possibly be inhabited and activated by the presence of a body. If “String Constructions” already made use of traditional materials and echoed traditional forms of (mostly female) labor within their soft-edged, morphing geometries, this new phase of Miyamoto’s work, coinciding with her maternity, manifested a sort of neo-primitive world, embracing a more confident and immersive relation with natural elements.

We might speculate that Ana Mendieta—in her references to pre-modern rituals and forms of dwelling—played a role in developing this new phase. Mendieta joined A.I.R. in 1978, six months after her arrival in New York, and there she presented her first two solo exhibitions. As Miyamoto recollects,7 she found in Mendieta a friend with whom she could communicate very openly—both sharing non-Western, non-white identities—and reflect on their own cultural differences from Western and American women. As a result of this exchange, Mendieta and Miyamoto co-organized “Dialectics of Isolation: An exhibition of Third World Women Artists in United States.” Opening on September 2, 1980, the exhibition included eight artists, of whom only Howardena Pindell was part of the A.I.R. collective.8 The exhibition produced a small publication, designed by Zarina and including a short text by Mendieta, in which, interestingly, she criticizes the American feminist movement for its lack of consideration for “the other.”9: 171–181). Miyamoto remembers the idea of the show coming from all A.I.R. members and being championed by Nancy Spero.] Each artist presented, alongside reproductions of their own work, brief statements, which featured a mix of poetic responses and polemical considerations of racial inequality and prejudices. The exhibition, which was successfully received,10 could now be read as an interesting moment of conjunction, as well as of passage, between the feminist struggles of the 1970s and an increasing awareness and interest in non-Western cultures by Western artists and institutions through the 1980s, culminating with exhibitions such as “Magiciens de la Terre” at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris in 1989. “Dialectics” was actually not the first exhibition to be organized by Miyamoto at A.I.R. or the first to include non-Western artists in its program. “Women Artists from Japan” (1978), for instance, was part of a series of exhibitions, hosted from 1976 onward by the collective, which included international artists external to the organization.11 Miyamoto notes the decisive role played once more here by Spero, with whom she kept a close personal and professional dialogue until her last days, as demonstrated by the performance she staged at Spero’s studio in 2007.

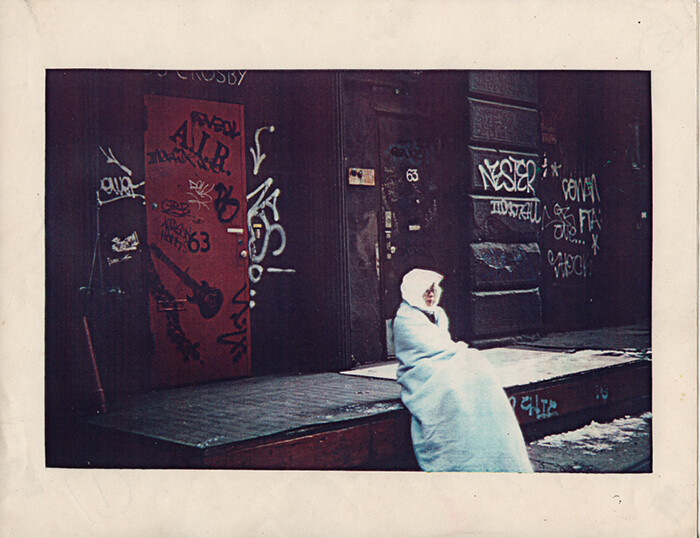

Through the years it became increasingly difficult for Miyamoto to meet the requirements of A.I.R. and she quit the organization in 1983.12 But the period she spent at A.I.R. was preparation for her later experience as a gallerist. Gallery Onetwentyeight, which took its name from the space’s address on Rivington Street, on the Lower East Side, opened in 1986 and, to this day, is the longest continuously running gallery of the area. The Lower East Side of those days was a highly depressed area, only superficially close to the East Village and its booming art scene of the time, and certainly even more distant from its present state of gentrification. When Miyamoto opened the gallery, the collectively run center for art and activism ABC No Rio was the only other art space in the area. While ABC was strongly imbued with political and social engagement, the so-called “Rivington School” brought together a number of artists from different countries, who Miyamoto remembers for their “extreme wilderness.”13

In opening a new gallery, a long and narrow storefront space, Miyamoto wanted to move away from the model of A.I.R., avoiding membership and gender limitations. While A.I.R.—even within the concept of a (flexible) collective—entertained the idea of representing artists, Onetwentyeight never relied on such relationships.14 On one hand, it became the space to elaborate, produce, exhibit, and occasionally sell Miyamoto’s work; on the other, it became a meeting point for what progressively became an open community. Miyamoto installed some of her own shows at Onetwentyeight, which witnessed another phase in her practice. From the early 1980s the work acquired a more performative character, often using the streets as a stage for actions and installations where Kazuko embodied different forms of travesty, playing the role of a variety of characters and personas, especially some considered socially marginal (as in the case of the work Waiting for the Carnival [1983], in which she dressed as a homeless person walking the streets of the Lower East Side).

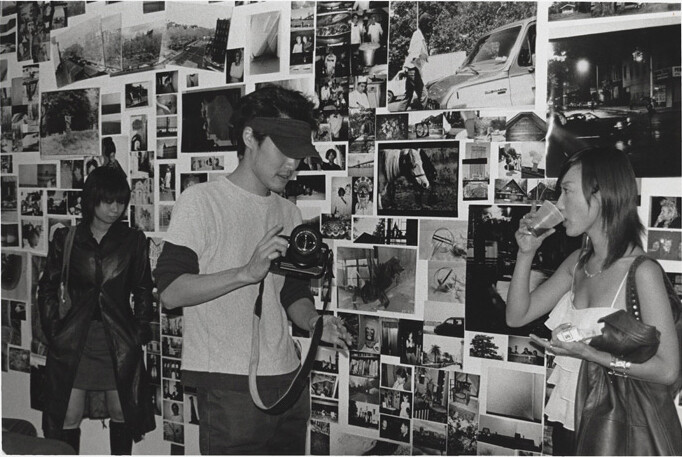

Miyamoto was, and still is, behind the better part of the gallery program. Initially, Miyamoto fielded exhibition proposals based on her friendships, drawing on an extremely generous attitude that eventually opened the gallery to unknown passersby eager to show their work or to collaborate on the gallery’s maintenance. Every year, about 9 to 12 shows were installed, announced by postcards. Soon, Onetwentyeight created a community of artists, friends, and dropouts that Miyamoto, or occasional guest curators, brought together in what she now recalls as “jam sessions.” These collective efforts were occasionally joined by renowned friends as well as occasional visitors who later became well-known artists. From the first category was David Hammons, who participated in a group show of black artists curated by Chris Morez (“he was sick in the head, but interesting…” Miyamoto recalls),15 as well as Spero and LeWitt, whose modular sculptures and maquettes have been produced and shown on the same premises for many years. The second category is composed of artists such as Piotr Uklański, who, Miyamoto recalls, “walked into the gallery in 1989 or 1990.”16 Common to these group shows, which surpassed the solo exhibitions in number, was, and still is, a rejection of hierarchical divisions between unknown and celebrated artists that fostered a spontaneous and informal atmosphere. One of the most recent examples is “Kimono Show” (October 17– November 16, 2014), which combined LeWitt’s wall drawing WD 731, originally conceived for Onetwentyeight in 1993, with a series of works featuring kimonos, some by Miyamoto herself and others by lesser-known artists,17 in a surprising series of juxtapositions that confirm once again Onetwentyeight as an island of freedom in an increasingly market-oriented city.

“Being Japanese you are minimalist anyway,” Miyamoto observed in a conversation with Christian Siekmeier (New York, November 2012, unpublished).

I am indebted here to Anne Marie Sauzeau Boetti and her accurate description of feminist turmoil in the New York art scene of the early 1970s. See “L’altra creatività,” DATA, no. 16/17, summer 1975. Following the founding of the Art Workers Coalition, a number of all-female artist collectives appeared in New York at this time, including the Ad Hoc Committee of Women Artists, Women Artists in Revolution (WAR), Redstocking Artists, and Women Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation (WSABAL).

Lawrence Alloway, “Kazuko,” in Kazuko Miyamoto (Berlin: Exile Berlin, 2013), 14. Originally published on the occasion of Miyamoto’s solo exhibition at Ginza Kaigakan Gallery, Tokyo, 1977. It must be noted that Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawing #815 (1997) is constructed upon a system of strings nailed to the wall, in what can be read as an homage to Miyamoto’s art.

It is worth noting how, at approximately in the same time but in different areas of the world, a number of female artists used obsessive and meticulous manual techniques within the realm of Minimalist and post-Minimalist languages, as opposed to the outsourced production of many male Minimalist artists. Here I am referring to Italian artist Dadamaino (1930–2004), Californian Channa Horwitz (1932–2013), German-Italian Irma Blank (b. 1934), and Indian Nasreen Mohamedi (1937–1990) and their questioning of the body and movement (Horwitz), time (Blank), and space (Mohamedi). The case of Miyamoto is particularly interesting, since she was personally physically producing LeWitt’s sculptures but trying to give them the industrial look that the artist was aiming for.

From Miyamoto’s early Minimalist-oriented pieces of 1970s to her photographic works of the 1980s and 1990s, from the sculptures and installations to the various performative activities, the role of the body in Miyamoto’s work became progressively prominent through the years. From the early 1980s, Miyamoto engaged her own body as well as those of other women in a number of actions and performances in private and public contexts. More recently, and with reference to traditional Japanese forms of theater and dance, she worked on a series of performances that have a ritualistic character and often use kimonos as props or instruments. An example is Improvisation on a Black Bird (2014), shown at Palazzo Collicola Arti Visive in Spoleto and later at Museo D’arte Orientale Giuseppe Tucci in Rome, both as part of the exhibition “The Pink Gaze.” On the first occasion, works by Sol Lewitt functioned as the background or elements of the staging. In this and other actions Miyamoto interacts and, at times, guides the movements of a second performer, which she relates to the work of traditional Bunraku puppeteers. I curated the exhibition “Kazuko Miyamoto. Bodily Tactics,” dealing with the role of the body in Miyamoto’s practice, at The Japan Foundation, New Delhi, January 23–February 28, 2015.

If Robert Morris’s Box for Standing (1961) could be registered as a distant reference for this work, it is interesting to consider how here Miyamoto has anticipated the use of Minimalist jargon as a vehicle for personal and affective agendas taken up by artists in the 1980s, especially Félix González-Torres.

From a conversation with Zasha Colah and the artist at Miyamoto’s apartment, New York, November 5, 2014. Indian artist Zarina Hashmi also remembers how the three of them—Miyamoto, Mendieta, and Hashmi—used to hang out in those days (from an unpublished conversation, New York, November 9, 2014).

The complete list of participants included Judith F. Baca, Beverly Buchanan, Jenet Olivia Henry, Senga Nengudi, Lydia Okumura, Selena Whitefeather, and Zarina.

There are differing accounts of the involvement and roles of the three artists in the conception and organization of the exhibition. While the catalogue reports the involvement of the three artists, the A.I.R. official website lists the show as “co-curated by Kazuko and Ana Mendieta.” Kat Griefen’s text “Ana Mendieta and A.I.R. Gallery, 1977–82” appoints Mendieta as the initiator of the exhibition (in Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory, vol. 21, no. 2 [July 2011

Kat Griefen, ibid.

Other shows of this kind included exhibitions on French (1976), Israeli (1979), and Swedish female artists (1981).

In the same conversation (November 5, 2014), she remembered: “Sometimes I couldn’t work too much for A.I.R. I was a single mother. I was working for Sol to support my living. I couldn’t work as much as they expected. So somebody complained and I quit. The majority had an upper-middle-class background. I had no class!”

See above.

As Carey Lovelace notes in her essay “Aloft in Mid-A.I.R.,” artist Agnes Denes left an uptown gallery to join A.I.R. A.I.R. Gallery, last accessed May 27, 2015, http://airgallery.org/about/history/.

Miyamoto, ibid.

Ibid.

The exhibition’s other featured artists included D Fenn, Kaitlin Martin, Lael Marshall, Mieko Craig, Maxwell Stevens, Nami Mo, Né Né, Sarah Katz, Sanae Maeda-Buck, Toki Osaki, Yuko K., Rob van Erve, Haruko Mochimaru, Tatsumi Hizikata, and Jesper Haynes.