In 1996, his body bloated, his liver consumed by cancer, and his work more popular than ever, Martin Kippenberger (1953–1997) set about his final series of self-portraits. Taking Théodore Géricault’s iconic 1818–19 painting as its point of departure, and working from photographs taken by his wife Elfie Semotan, “The Raft of the Medusa” eventually came to include over a dozen each of paintings, drawings, and lithographs, as well as an eight-by-fifteen-foot rug that depicts the raft’s schematic layout. This sprawling multimedia series has been reunited for its first New York exhibition at Skarstedt, organized in collaboration with the Estate of Martin Kippenberger at Cologne’s Galerie Gisela Capitain.

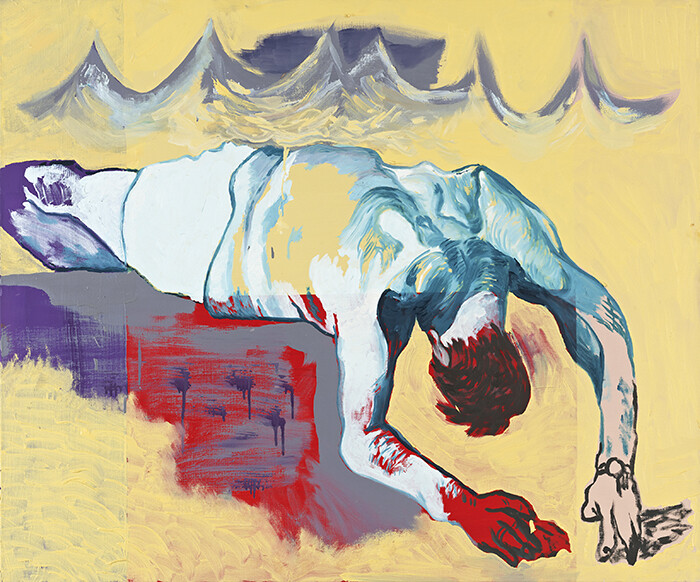

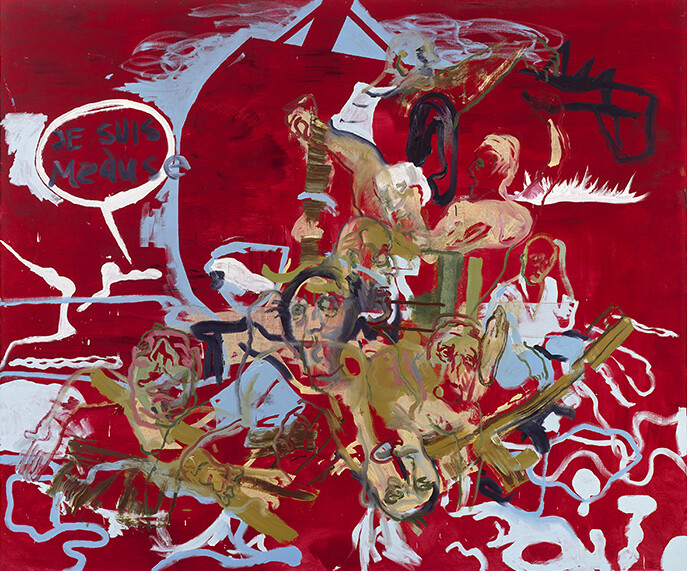

The project has been divided into four elements. The first floor provides a preliminary or preparatory overview: a collection of drawings on hotel stationary as well as the rug and an oversized painting that, here, appears as the series’ linchpin. The second floor, the gallery’s largest exhibition space, features the body of “Medusa”’s 16 paintings. On the third floor, a group of lithographs produced after the “Medusa” work opened in Copenhagen acts as the images’ afterlife; ethereal yet straightforward, these prints announce the end of their author—one of them, depicting a detail of the raft and captioned “the end,” does so literally. The stairway that connects all three floors displays Semotan’s photographic studies of the artist; fat, nearly or totally naked, adrift on a mattress, and alone in an empty studio, Kippenberger poses as the many imperiled passengers dead or dying on Géricault’s ill-fated raft.

The episodic hanging at Skarstedt provides a map through the tangle of interconnected work—a welcome, if sober, strategy that lends both clarity and seriousness to a collection that could just as easily come off as neither. It is perhaps tempting to bemoan such a straightforward exhibition of Kippenberger’s final self-fashioning in the sober surroundings of an East Side blue chip gallery. What happens to bar-room humor and inside jokes in such spaces? Is a beer gut still embarrassing when it’s framed by uptown architecture? I’m not sure. But in any case, nothing is lost. We know that Kippenberger’s work was funny (or at least that it tried to be). We know that it championed failure and embarrassment, derivation and bad taste. But I doubt we know how miserable it was.

Misery was in fact a central theme in Kippenberger’s practice, appearing in some of the artist’s earliest projects. In 1979, Kippenbergers Büro [Kippenberger’s Office], the working/living/exhibition space founded in Berlin’s Kreuzberg district, organized the group exhibition “Elend [Misery]”). From here, the theme can be traced through his Alkoholfolter [Alcohol Torture] (1981–82), his “Magical Misery Tour” of Brazil (1985–86), the collection of paintings and images of the artist beaten and bandaged under the title “Dialog mit der Jugend [Dialogue with Youth]” (ex. 1979 and 1981), and his crucified “Fred the Frogs” (1988–90). Yet, in discussions of Kippenberger’s work, notions of failure and embarrassment are often privileged over those of misery and suffering. This is likely due to a willful resistance to sentiment, and the sense that misery is too close to the adversity-writ-virtuosity of the tortured, starving artist, and thus to the lingering specter of modernism. It has no business in postwar painting unless appearing ironically and at arm’s length, we think.

Within the bounds of Skarstedt’s gallery, misery is given its due. This is good. Yet boundary transgression is Kippenberger’s gambit, and so the rigid categories do not hold. For example, the drawings displayed on the first floor did not precede the paintings, as the hierarchy seems to suggest. Rather, they came afterward, and connect the “Medusa” paintings to Kippenberger’s lifelong practice of drawing on hotel stationary, to the production of evidentiary ephemera of an always-traveling artist-persona. Similarly, elements in paintings on the second floor reach back to prior work about value and exchange. In particular, international coins, adhered to a few of the paintings, invoke earlier works covered in currency. The pocket change of an international traveler, this found material also suggests that the raft is not a last stop on the artist’s voyage, but a vehicle both connecting and containing his many destinations.

Categorical division is ultimately upended in favor of accumulation and simultaneity. Through Kippenberger’s bloated figure, Medusa embodies all positions—all possible destinations. Géricault’s painting depicts the moment when the raft’s survivors see their potential rescue ship in the distance, unsure if they are seen in return. It is a moment that contains rescue and peril, but also subject and object, seeing and being seen. For an artist whose lifelong practice was the relentless and unbounded appropriation, accumulation, and performance of ideas, conversations, images, and experiences, a final self-portrait was doomed to miserable over-determination. Cannibal and cannibalized, savior and saved, body part and whole, past and future are cast in the series as positions occupied simultaneously. In their totality, these self-portraits don’t champion the figure of the artist, they overwhelm him, a verdict that Kippenberger announces in his largest painting from the series, an untitled study in red, with a speech bubble that reads, “Je suis meduse.”