Exhibition spaces are, at times, haunted by the work they housed in the past. Walk through a museum and former installations will reverberate. Think of the Arsenale in Venice, visited by the ghosts of biennials past. This is all the more evident in galleries. The steady relationship between a gallery and an artist translates to a specific kind of knowledge by way of following, by way of making connections when seeing an artist return to a space with new work.

“Provenance,” Amie Siegel’s first exhibition at Simon Preston, in fall 2013, included a video, Provenance (also from 2013), that presented the artist’s research into the trail of value creation that occurs in auction houses. Tracking pieces of furniture created by Le Corbusier for buildings in Chandigarh, the Indian city planned by the Swiss-French architect, the work delineates the travels of tables, chairs, and settees from fancy apartments in New York and London back through their sales at auction, through auction previews, shipping crates, and finally their origin in India. Even if they are the video’s subject, these objects don’t have magical faculties, they do not carry an inherent value just by virtue of the attention paid to them; rather, value is accumulated by way of circulation. Provenance follows to become proof thereof: after it was produced, it was sold at Christie’s, London, in the Post-War and Contemporary Art Sale of October 19, 2013, which is documented in a short video, Lot 248 (2013).

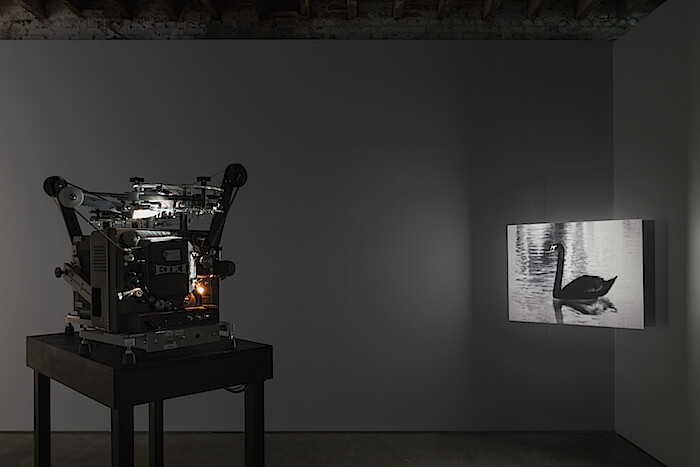

In the context of Siegel’s current exhibition, “The Spear in the Stone,” her 2013 show stands to be more than a phantom limb. She returns to the gallery with two new works, both of which employ a similar study of histories of objects that illuminate our received ideas of them. Fetish (2016) is a 10-minute video of the nighttime cleaning of the Freud Museum in London. It’s a work of dust and cloth, honing in on two male employees as they remove objects from shelves, wipe them, clear off the residue where they were, and return them. Double Negative is an installation of two synchronized 16mm films projected onto opposite corners along with a 17-minute HD video. The films display Le Corbusier’s famous Villa Savoye in Poissy and its inverse, a black version of the modernist white concrete villa, in Canberra, Australia, which now houses the Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Images of these buildings are projected in the photographic negative, reversing light and dark, making the white building seem black and vice versa. The video cuts to the black Villa Savoye, and describes the activity that now takes place within it: a strained, painstaking digitizing project of the Institute’s collection.

This is slow work. The vacuuming of Freud’s famous couch in Fetish drags on, as do the views of the pond in Double Negative, as do the latter film’s long footage of pieces of the Institute’s collection being scanned (the scene then cuts to that of a camera resting on a scanner, then a computer screen displaying the image as it is captured and adjusted, then again). This is not archive-obsessed documentation, not simply the addition of an aesthetic layer of the filmmaker’s gaze onto preexisting materials. This microscopic research practice is the frame through which the viewer is meant to see that things reflect the meaning we bestow upon them over time and we then treat them accordingly. Freud’s objects, from his couch to his collection of statuettes, stand in for his dominance over the way we think about human nature. The materials Siegel is dealing with are explosive—especially in Double Negative, which charts the current discomfort in Western society with the history of ethnography, marred by colonialism. While these initially read like a poetry of small things, a meticulous cataloguing of spaces, places, and the things that fill them, they are actually a way of narrating the anxious meanings these take on with time.

Presented next to each other, Double Negative and Fetish outline a path to understanding Siegel’s emphasis on movement and the interconnected nature of the passage of things, be it a building, a video clip, or a collection. As disparate as these two works’ subjects may be, the process they describe—a metonymical lens, where an attribute or a thing stands in for a whole it was cut off from—suggests both a glance back to Siegel’s other works, compiling an index of her studious focus, as well as furthering her practice of addressing details as a way of seeing the systems they are part of. Alongside the phantom presence of “Provenance,” this gallery presentation makes clear that Siegel’s work privileges continuous viewing from one exhibition to the next, which also reflects the artist’s own methodology of slow, sustained observation.